One of my kid’s earliest visible tics entailed touching all the tables in our local café before sitting down at ours. Most people would politely ignore him. Occasionally there would be a sustained curious or even hostile look from someone enjoying their coffee, as though I was a bad parent for allowing my kid to do something he shouldn’t be doing. I have tried not to treat his tics as something for me to control. They belong to him. We barely speak of them. But walking into the café, I would think to myself: Don’t these assholes know that not everyone is neurotypical? That it’s utterly fucking wonderful that there are people who aren’t? What a bunch of boring dopes, looking askance at deviation from norms! Oh wait, am I getting embarrassed by this? Are my cheeks reddening? I am such a coward right now.

I’ve gotten better since then at dwelling in the awkwardness. I’ve learned from him.

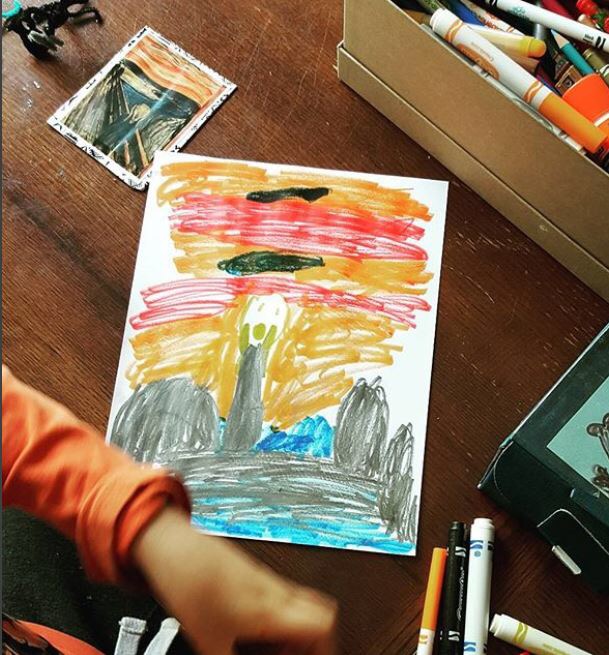

He spent the last month of second grade pacing at the back of the classroom, making movements that appeared to be slaying dragons and throwing fireballs at ruthless demons. His teachers tried to engage him in school activities, but largely failed. He had “turned away from the learning,” they said. Because he was struggling with it, feeling frustrated and embarrassed that he couldn’t do what others seemed to be doing with ease.

I was told that what he needs is an “individual education plan,” or IEP. An IEP sets different standards for evaluation of learning, and it mandates that the school provide certain kinds of help. But to get an IEP you need to pay for an “assessment” by a child psychologist who specializes in learning challenges, issues, differences. It costs about $2800. Beyond the reach of many.

Looking further into it wasn’t exactly reassuring. The people I could hire all seemed to research things like “how this sad thing is getting in the way of what really matters: school success,” “how to make your child into their best self by helping them excel at school.” With the assessment completed, you are equipped to “advocate for your child.” If you don’t have the money, that’s tough I guess.

And then you watch all these other kids—neurotypical kids—arrive with their IEPs, secured through the intervention of expensive experts. It is a way to get a bespoke educational experience for your child, even in a public school. If you can afford the investment, you’d be stupid not to. Imagine the future returns on their human capital! And if lots of people are doing it, you can’t be the ones left out. It’s grade school as rat race. Maximize your advantage. Otherwise your child will far further and further behind, feeling less and less capable, more and more substandard, more and more judged.

The psychologist I called in June had no space in her schedule until November.

Sarah Brouillette

Sarah BrouilletteI tell him that he lacks nothing. He is kind, loyal, helpful, and loving. What else matters? But at school mastery means conquering the math curriculum, which is geared now toward development of young computer coders. It means neat handwriting and correct spelling—activities of conformity and mirroring rather than of creativity and deviation. Stay inside the lines! It’s classic stuff.

For a long time, his consuming worry was what his future job would be.

“My love, you are a kid. You don’t need to think about this now.”

“But I am thinking about it.”

“You can live with me forever, no matter what.”

“No thanks.”

He needed assurance that there were jobs he would be competent to do. They all sounded too hard to him. He didn’t want them to require a lot of training. We would do research and map out what the entire day would look like for certain people: gravediggers, UPS delivery people, flower shop employees. Airport grounds crew became a particular focus. He wept, trying to understand how they knew where to go and when.

“Babe, they have watches, and there are alerts when the aircraft arrive and depart.”

“I can’t tell time.”

We’ve read a lot of books about childhood anxiety—managing the “worry bully”; “you are not your worries”; “kick that jerk out of your head.” They are very popular titles at the public library nearest to us. There are waitlists to check them out. All these stressed out kids. They are so worried about, so watched over. Is it the problem of their futures? Of any future? Intensifying competition for an increasingly paltry prize. For something that never was a prize. It is no wonder that “delays,” “challenges,” neurological “deviations,” become such a focus, and appear so laden with risk.

I mainly wonder if he will find help when he needs it. It’s not the same as asking if my investment will pay out.

He paces a lot at home now, when he’s anxious and has nothing sufficiently distracting to do. Sometimes when he is especially deep into it, he seems to be turning an invisible door knob to enter another room. I’ve asked him if I can go in through the door too, but he shrugs me off: “Mom, don’t worry about it,” “Mom, nevermind.” Because he can tell it sort of gets to me—being left on the other side, far from wherever he’s going.