In August of 1938, a single mother applied to leave her six-year-old son, Jack Gilbert Graham, in the care of an orphanage in Denver, Colorado. Daisie E. Graham had been separated from Jack’s father, William, long before his death from pneumonia the previous year; she’d been struggling to support both her 15-year-old daughter, Helen, and her own terminally ill mother. William’s sudden death had left Jack fatherless, and officially an “orphan.”

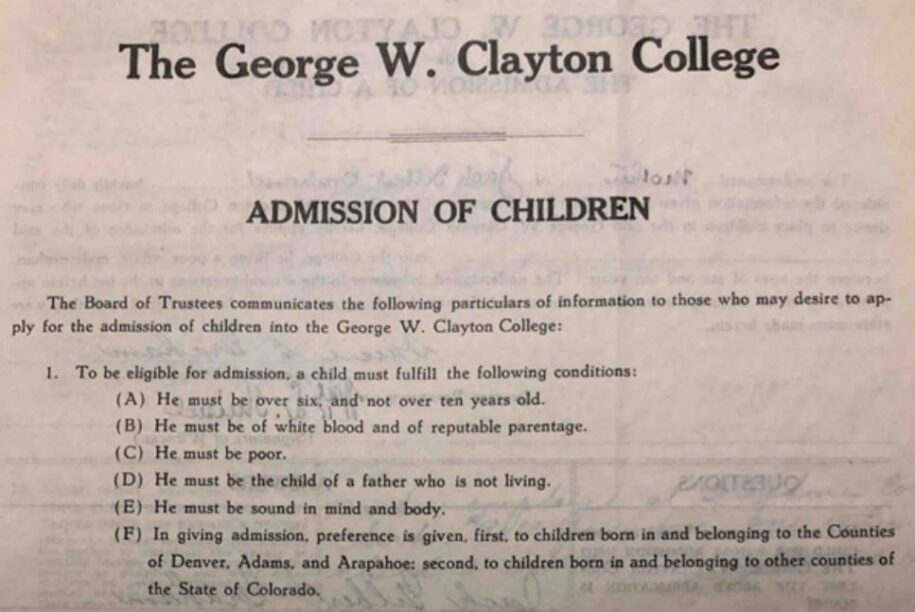

The Clayton College for Boys, built with funds donated by merchant and philanthropist George Washington Clayton, was founded in 1911 as a refuge for “poor white male orphans … born of reputable parents.” The substantial, ornate two-story building of gray stone and rose-colored brick still stands on Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard, a few blocks north of the Denver Zoo; with its terracotta tiled roof, iron door lanterns and plate glass windows, the 112-year-old building gives the impression of a church. It looks a bit out of place—or out of time—in the midst of the SUVs in the parking lot and modern buildings nearby.

In the weeks after Daisie climbed the stone steps of Clayton College to apply for Jack’s admittance, he was screened for illness and family history thereof, and declared free of tuberculosis, syphilis, epilepsy, insanity. Letters of character reference for both Daisie and little Jack were sent to the College by friends and neighbors to help his application along.

“I know Mrs. Graham to be working at the Telephone Company to support her son and help her mother,” wrote L.R. McLean, D.D.S. “I believe her boy Jackie to be a first class little fellow.” Daisie’s employer testified to the great burden Daisie was under, including constant financial hardship. Her supervisor wrote that “the demands of her mother’s illness result in an unsatisfactory environment for raising children.” Having met all the requirements for admission, Jack entered the orphanage the following month, in September.

“The Will under which we operate requires that we only serve boys who are needy, and it is upon this assumption that Jack is accepted,” Superintendent Alvin R. Jackson wrote to Daisie. “Should your circumstances change…you will be expected to inform us and ask for the return of your boy.”

And so it was that young Jack began a new, strange chapter of his bleak childhood. He would call the orphanage home for the next five years.

In the application, Daisie had described Jack as liking school, and having a particular interest in machinery and music. “He is not hard to handle,” she wrote. But in early 1943, as the Second World War raged, Jack befriended a young girl working as a housekeeper in the neighborhood. After showing Jack where her employers hid the key to their family home, Jack used the key to enter the house, each time stealing money; a total of $2.15 (about $40 today) on two separate visits. He was just eleven years old.

Superintendent Jackson sent a letter to Daisie, who was by then married to John Earl King, and living on King’s ranch in Toponas, Colorado.

“The third time, he was caught in the kitchen by the lady of the house,” he wrote. “It appears that instead of things getting better with Jack, they are getting worse.” The superintendent noted, too, that Jack had run away from the institution several times. He suggested Jack leave the orphanage.

On the torn and tattered summary of Jack’s file at Clayton College, he was given a Dishonorable Discharge in March 1943. His file included the note: “Constantly in trouble. Discharged to mother.”

Daisie sent Jack to live with relatives. When he turned 16—the war over, America victorious and entering a new period of optimism—he hit the road and joined the Coast Guard using forged ID papers. A year later he was discharged as a minor after having been AWOL for forty-three days; he drifted from Colorado to the frontier territory of Alaska to stay with his half-sister, Helen. He found work at Elmendorf Air Force base.

When Jack returned to Colorado in 1951, though not yet twenty, he embarked on a life of crime.

According to Mainliner Denver, Andrew J. Field’s authoritative account of Jack’s crimes and trials, Jack forged and cashed some forty bad checks while working at the Timpte Brothers Automobile Company and skipped town, becoming one of the Denver District Attorney’s six most wanted men that year. He bought a convertible and drove around the country, ducking warrants for theft and forgery, visiting Salt Lake City, Seattle, Kansas City, Saint Louis.

In Lubbock, Texas, police tried to pull Jack over for a traffic stop. He led them on a wild car chase, crashing through a roadblock and careening into a ditch. He surrendered only after officers opened fire on his battered convertible. In the car, police found cases of bootlegged whiskey—contraband he’d been smuggling into a “dry” Texas county—and a .44 caliber handgun.

Jack spent sixty days in a Texas jail before being extradited to Colorado, where he pled guilty to forgery charges. At the sentencing hearing Daisie repaid some of the stolen money to Jack’s employer and asked the judge to go easy on her son. A probation officer’s report described Jack as showing “very little concern” over the offense, and Daisie as “overprotective” of her son. Jack was put on probation. Briefly on the straight and narrow, he somehow was cleared to work for the Atomic Energy Commission. He made restitution payments, and met a woman he wanted to marry.

By December 1953 Jack, his wife Gloria, and their two small children had moved into a house in Grand Junction, Colorado, bought with a down payment from Jack’s mother; Daisie’s only condition was that she have her own living quarters in the basement she could use when visiting.

Just a few months later, Daisie became a widow for the second time, and inherited a small fortune. Hoping, perhaps, to make amends with her troubled son, she proposed opening a drive-thru restaurant that Jack could manage. He agreed, becoming wholly dependent on his mother. But it wasn’t long before Jack found a new way to make money.

Early one morning in spring 1955, Jack parked his new Chevrolet pickup truck on a set of train tracks outside Denver, and stole away. A freight train plowed through the vehicle, destroying it, and netting Jack several thousand dollars in insurance money. He was on to something.

In September 1955, a gas explosion destroyed part of Daisie’s newly-opened Crown-A restaurant, where Jack was working as manager. The insurance company flagged the explosion as suspicious but couldn’t prove malfeasance. Jack filed an insurance claim, which paid out. There were murmurs among neighbors and friends that Jack, known for his checkered past and tense relationship with his mother, was the saboteur behind the destruction of both the truck and restaurant.

One month later, as Daisie prepared for a trip to Anchorage to visit her daughter Helen, Jack hatched a new plan. A plan that would remove from his life the two things that he believed were keeping him down—a lack of money, and his mother—no matter the cost.

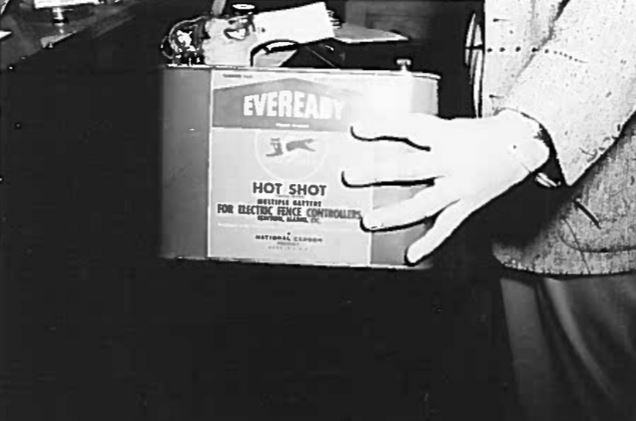

After buying the requisite tools and equipment, Jack sat down in the basement of his family home and got to work. He assembled twenty-five sticks of dynamite, a timing device, an Eveready six-volt “Hot Shot” battery and two dynamite caps into a compact time bomb. He wrapped the bomb up, packed it inside Daisie’s heavy Samsonite suitcase, and loaded the case into the trunk of her ‘55 Chevrolet sedan. Then Jack and Gloria drove Daisie to the airport. It was November 1, 1955.

After saying goodbye to Daisie at the gate, Jack and Gloria stopped for a snack at the airport coffee shop—but not before Jack bought an insurance policy on Daisie’s life from a vending machine at the terminal, a common practice in a time marked by frequent air crashes.

The Douglas DC-6B, piloted by WWII veteran Lee Hall, exploded in midair minutes after takeoff, creating a nightmarish fireball in the open night sky. One witness described the fiery explosion as being “like a shooting star.” Another witness, Norman Flores, happened to step outside on the porch of his rural home near Longmont, Colorado just before the bomb detonated.

“It was a real nice moonlight night, just as pretty as could be,” he recounted. “And I saw this airplane. Lights were flickering on it. Then all of a sudden there was an explosion, and it was so terrific it shook the house… When it hit the ground, a big orange mushroomed affair went up, and from then on it just burned.” Another witness described the burning wreckage of the plane as looking “like an atom bomb.”

All forty-four people on board United Flight 629, including Daisie, were killed. It was the first-ever act of sabotage against a commercial airliner in the United States.

In the immediate aftermath of the bombing, first responders were stunned by the carnage and horror of the scene. Bodies were strewn among the wreckage; everywhere, fires burned in the freezing night. Lead Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) investigator Jack Parshall quickly arrived from Kansas City and asked a swarm of newspaper photographers to refrain from taking photos of the bodies. Most complied, but a few sneakily snapped pictures: of shoeless feet protruding from rubble, of a ghostly, severed hand. One enterprising group from the Denver Post flew a helicopter over the scene, hovering low enough to get detailed photographs and angering investigators.

Within hours, a team made up of local law enforcement, CAB, the Civilian Aeronautics Administration (CAA) and United Airlines officials began the grim work of determining what had brought down United Flight 629. Together they launched an inquiry, unprecedented in scale, which would soon reveal an unprecedentedly monstrous crime.

With the help of the FBI criminological laboratory, an investigative team of aviation experts collected as much of the plane wreckage as they could and painstakingly reconstructed the destroyed Douglas DC-6B in a massive warehouse. (Photos courtesy of Denver Police.)

Within days, investigators were confident that a massive blast had brought down the plane. And with the consensus that the plane had been destroyed in an act of sabotage—a crime never previously seen in America—United Airlines stopped taking questions from reporters and the FBI launched a criminal investigation, igniting parallel outbursts of bureaucratic secrecy and media sensationalism.

Hundreds of FBI agents fanned out to interview anyone connected to the passengers killed in the bombing, trying to determine the target. By analyzing fragments of debris from the crash, investigators identified the pieces of luggage closest to the initial explosion. Eventually, based on the near-total obliteration of her Samsonite suitcase, they settled on the likeliest target: Daisie King.

After interviewing both Jack and Gloria, the FBI’s suspicions focused on Jack. They executed a search warrant at his home, netting a wealth of evidence, and Jack was arrested on charges of sabotage. Following interrogation, Jack signed a confession, admitting to planting the bomb that killed Daisie and forty-three others on board Flight 629. (Evidence photos courtesy of Denver Police.)

An Eveready “Hot Shot” battery found in Jack’s home

After Jack’s arrest, the unfolding story of the bombing rapidly mutated from a national fascination into a political tool. J. Edgar Hoover helped whip up a media frenzy by writing a syndicated op-ed framing the plane bombing as part of a national crime wave that required Americans to increase their support of law enforcement agencies.

To ensure that Jack would face the death penalty, prosecutors withdrew the sabotage charges—he’d broken no explicit law—and replaced them with a single charge of murder in the death of Daisie King, a crime for which they were confident they could obtain a conviction. Jack attempted to mount an insanity defense, but was assessed by psychologists and found legally sane and competent to stand trial.

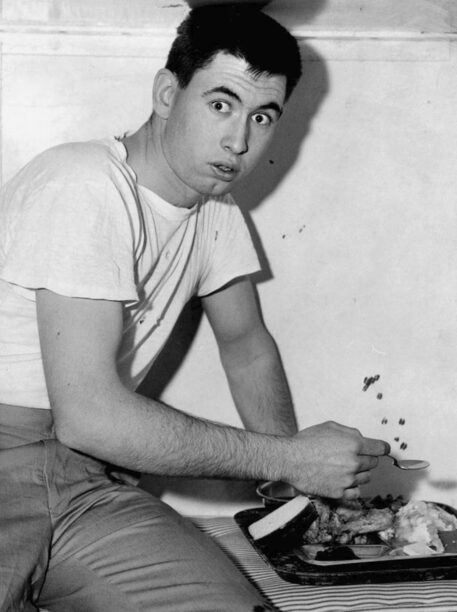

Days after the decision, Jack was found slumped in his cell after attempting to hang himself. He was placed on 24-hour watch in the psychiatric ward of Colorado General Hospital. After the insanity defense was abandoned by his attorneys, Jack was sent back to the Denver County Jail to await trial.

Jack Gilbert Graham’s trial in April 1956 was the first ever televised in the United States, after a consortium of news organizations challenged the law, recently passed by the Colorado Supreme Court, forbidding courtroom photography of any kind. Their challenge succeeded, and a judge denied Jack’s request that television cameras be banned from the courtroom.

A special booth was built at the back of the courtroom to house camera equipment; one local paper had a direct telephone line installed from the court to its editorial office. The first day of the trial, hundreds of onlookers swamped the court’s hallways and grounds; people brought lunches for the nightmarish picnic event.

Jack’s callousness was amplified in media coverage; every detail of his heinous crime was revealed from coast to coast. He was a monster, entirely without remorse. Asked in interviews with police and psychiatrists about the innocent people he’d killed, Jack shrugged and said that there could have been a thousand dead as the result of his actions; he simply didn’t care.

During the prosecutor’s closing arguments, Jack’s half-sister Helen left the courtroom, went to a coffee shop and got drunk. Some hours later, a police officer found her slumped across the steering wheel of her station wagon and chided her for her drunkenness; she replied, “If you’d just found out your brother killed your mother, you’d get drunk, too.” She refused the offer of a ride home from the sympathetic officer, and demanded to be taken to jail.

Released the next morning, Helen went directly to the offices of the Denver Post and, as she’d promised to reporter Zeke Scher during the trial, wrote a letter which would be published the next day:

What Jack did seems too horrible to be true. But I can’t hate him. He’s guilty – and I want him to die. I love him, but then I had a mean dog I cared for a lot…

What kind of a mother was [Daisie]? Whatever mistakes were made, she made them thinking they were the right things to do.

What kind of a grandmother was she? This was where she tried to make good all the mistakes that she had made with Jack and me… A loving grandma, and much missed.

Daisie was temperamental. She was hard to get along with. I wasn’t close. All these are true, but there is more, one thing more that cancels it out. I loved Mom… She loved her son the best of anything in the world. Me, too. But he was her special pride. She did everything for him she could. Too much maybe.

She concluded her letter with a final thought on Jack, now convicted and sitting on death row.

Don’t worry. He is not the calm, unemotional man he seems. There is hell [in] back of those dark eyes. He is suffering. Justly suffering. I know this, and I feel pity for him.

After turning in her letter to the Post, Helen got in her car and drove the 3,300 miles back to Alaska.

The story of Jack Gilbert Graham raises questions that are as relevant today as they have ever been. Can nonviolent people ever hope to live in peace alongside the violent? How should a society handle people who have no qualms about destroying others? Can we ever really know what drives someone to kill?

It’s tempting to believe that if Jack hadn’t been sent to the orphanage as a boy—if he hadn’t lost his father, and stayed with his family—he might never have become a stone-cold killer. But it’s possible, too, that Jack’s miserable youth wasn’t what drove him to commit mass murder.

Maybe Daisie wasn’t being honest when she described Jack as being “not hard to handle” in the application to Clayton College. Perhaps she couldn’t handle him, and made a choice to protect the rest of her family by putting Jack in the care of others.

Or maybe Daisie was the troubled one. In an interview with FBI agents before Jack’s arrest for Daisie’s murder, Helen described their mother as temperamental, and “the kind of woman who could never find happiness.”

“She was never calm… Easily hurt, and she pouted a lot,” Helen told investigators, adding that Daisie could be “wonderful when she was relaxed, but you never knew when that was going to happen.”

Maybe Jack’s loss of his father and subsequent abandonment by his mother – no matter how valid her reasons at the time – hardened him, dulled his capacity for empathy and planted in him a dark seed, one that would grow into a dark and vicious need for revenge. Or maybe he was one of those rare children cursed with antisociality, who are born with a desire to cause suffering.

The jury deliberated for sixty-nine minutes before declaring Jack guilty of first-degree murder. They recommended a sentence of death.

Jack’s attorneys filed a motion for a new trial, which was quickly dismissed. They then filed a final appeal to the Supreme Court of Colorado, introducing the new expert opinion that Jack had been traumatized by his years at Clayton College. In his only direct address to the court, Jack protested his attorneys’ futile attempts to save his life, saying they had filed the motion and appeal without his permission or consent. He wanted to die.

On January 11, 1957, he was led into the gas chamber, strapped to a chair, and in front of a small audience, mechanisms were engaged. At 8:08pm, Jack Gilbert Graham—son, brother, father, orphan, husband, murderer—was pronounced dead.

Today, any child in need – no matter their skin color or gender – can be accepted and cared for at the institution now known as Clayton Early Learning. The orphanage that once accepted only boys of “pure white blood” now stands on a street named after the greatest advocate for human rights of the past century—even though the agency that brought Jack Gilbert Graham to justice also did its best to destroy that same man’s life.

Despite advocating for nonviolence, Martin Luther King, Jr. noted that all societies accept self-defense as moral and legal: “The principle of self-defense, even involving weapons and bloodshed, has never been condemned, even by Gandhi,” he wrote, acknowledging that there are evils in the world that might need to be fought. A position that Daisie King might have understood, though in the event, not well enough.