As I walked into Johannesburg’s Constitution Hill, the feeling of being watched, of being on stage, stayed with me. Though the complex now houses South Africa’s Constitutional Court, the “Old Fort” had been a notorious apartheid-era prison; today, one of South Africa’s highest courts conducts business amidst tours and historical exhibits and shows and concerts. “We have now reclaimed this space as we have reclaimed our country,” as Lwando Xaso put it in a blog post at the Constitution Hill website. “We are not proud of the history of the site but we are proud of what we have done with it.”

I was here for the Afropunk festival, which, after twelve years and stints in Brooklyn, London, Paris, and Atlanta, had finally come home. A few hours after the organizers had announced the Joburg dates, my best friend decided that we would both be there, and so we flew to South Africa from Zimbabwe. From the thirtieth to the thirty-first of December, thousands of black people would descend on Constitution Hill. We would all ring in the new year together.

I spent one of the days before the festival wandering around Museum Africa in Newtown, Johannesburg, just a few minutes away from the Afropunk site. The museum is a mix of kitsch, ethnographic objects, and high art that speaks to South Africa’s past and present. Located in a former market, it retains an airy openness, comprised of three floors connected by a winding network of ramps. This accordion-like design, in addition to the sheer volume of artifacts and exhibits in the space, makes it difficult to decipher where and how one should begin. Standing on the first floor, I turned right, to an exhibit on South Africa’s intellectual history.

The first panel that the visitor encounters features Sara Baartman, the Khoisan woman kidnapped from South Africa in 1810 and paraded around Europe as the “Hottentot Venus.” The panel on Baartman explains that “she was postulated as symbolizing the direct opposite of European modernity and classical beauty: in effect she supposedly epitomized the very essence of African heathenism and the incontestable form of African ugliness.” Baartman, made into a traveling freak show of black abjection, died in Paris in 1815. Her skeleton was displayed in the Musée de l’Homme until the 1970s. After a long campaign, the South African government finally repatriated Baartman’s remains in 2002.

Images like these haunt black cultural production. Staring at the image frozen in time, one is compelled to mount an argument against it, to reject the distortion of blackness filtered through a white gaze. Or, you might be moved to create because of it, entranced by the affirmation that you do have a past and a history.

To be photographed and seen—to prove I was there—is an integral part of the music festival experience. Each festival has its own aesthetic, one first organically developed among the original attendees and then carefully catalogued and sold back to them by the fashion industry. The Coachella look is the appropriative white flower child; Afropunk’s is “Pan-African with an edge.” There has been a recent explosion of this type of mass event that centers on black joy, culture, and fashion—all-day dance parties, the now-derided brunches, your occasional historic movie premiere. But maybe those familiar with the resonances of black life across the diaspora would argue that there is nothing new here. It is an old form of communion, as much about seeing as it is about being seen.

The long, broad steps to the grounds at Constitution Hill served as the unofficial runway at the festival, the place where you, the festival-goer, debuted your look. This ritual was sacrosanct. On a day when the weather was warmer than I anticipated, I debated dispensing with the long blue kimono I had worn, but my friend wouldn’t hear of it. “Keep it on until you pass the stairs,” she commanded, and I obeyed. The stairs led to a sea of young black people in Ankara prints, statement necklaces, piercings, bold lipsticks, fresh kicks, and other elements of what has become a global Afrodiasporic style. The hair—dreadlocks, afros, box braids, cornrows, cuts, and fades in all colors—was itself a testament to black culture, to hours spent with your head nestled between an older woman’s thighs, your tailbone aching from sitting; the buzzing of the clippers by your ears amidst raucous laughter; and the relief you feel when you check yourself out in a small handheld mirror after hours of holding your neck in stillness. My hair was in dreadlocks that had been recently re-twisted in a busy Harare salon where the aroma of the chicken being cooked outside mixed with the cloying floral notes of shampoo and hair gel.

The looks at Afropunk called upon the glitchy ’90s futurist cool embodied by Missy Elliot and Erykah Badu: black, but not of this world or time, bored with conventional notions of gender and being. No, they stretched back to photographs of our parents in the ’70s, back to images of ancestors, hair rubbed with ochre, coils of copper around their wrists. Street style photographers canvassed the stairs, stopping participants who had nailed the Afropunk aesthetic. Their transactions were quick and expert: a few clicks, a look at the camera’s screen for approval, then a wave of thanks to the photographer. Everyone seemed used to this, all celebrities who were finally, upon entering the grounds, being treated with the deference they were owed. The biggest photographer there, the one you wanted to stop you for a shot, was the South African stylist, artist, designer, and general purveyor of African cool Trevor Stuurman. He had set up shop by the stairs, capturing participants against a marbled gray background for a feature that later appeared on the British Vogue website. A caption beneath one of the shots he posted on his Instagram account declared, “AFRICA YOUR TIME IS NOW.” Self-fashioning as revolution.

In the early afternoon of the first day, before the grounds filled up, I watched a tall woman dressed in a Mad Max–style leather outfit, her hair cut in a cropped bob, face partially covered in sunglasses, pose for a photographer in the sandy area by the stage. Next to her, another woman danced to the music, arms held out, energetically kicking up the sand with black combat boots.

I imagine this made for a very beautiful photograph. On the grass next to me, my friend dubbed this performance “carefree, but aware of your best angles.”

On the humiliating reduction of her public image to an Afro, Angela Davis once complained that the nostalgic aestheticization of the black radicalism of the 1960s flattened “the politics of liberation to a politics of fashion.” But the merger of black lewks and black liberation has, by now, become a central part of the Afropunk brand.

Solange Knowles didn’t make it to Joburg; she canceled her performance just days before the festival, disclosing a long battle with an autonomic disorder in an Instagram post. She would have been a fitting headliner for the first Afropunk festival on African soil: an avid Instagram and Tumblr user—borrowing explicitly from black artists across the diaspora—she has, in recent years, popularized a certain way of looking upon blackness, grounded in a commitment to self-documentation and black glamour, providing the sounds and color palette for #blackgirlmagic. Her 2012 video for “Losing You,” shot in the township of Langa, Cape Town, featured Knowles dancing and posing among Congolese sapeurs, a sumptuous display of a certain kind of moneyed black cool, the kind that requires a passport and a willingness to accept roaming charges. Her 2016 album, A Seat at the Table, was a loving ode to blackness at a time when it felt particularly under siege in America. Monochrome greens, creams, and pinks accompanied the visuals for the album.

Afropunk’s connection between fashion and black liberation began with the 2003 documentary by James Spooner, originally titled Afropunk: The Rock and Roll Nigger Experience. It’s a 66-minute dialogue among those who would be cast out as black freaks, punks making art in mostly white scenes. In candid, often funny interviews, they talk about being fetishized, being rejected by parents, and chafing against narrow ideas of what it means to be black; in one scene, the musician Tamar-kali Brown thumbs through a collection of ethnographic portraits of African subjects. As she speaks, the camera zooms in on faces with piercings, elegant scarification marks, hair in intricate geometric patterns. Brown narrates her attraction to the punk aesthetic not as a flight from, but as a loving embrace of her black identity:

And so when I first started seeing images of punk—like this really bright-colored hair, safety-pin piercings and things like that, it was pretty much on that same level, just like a contemporary, Eurocentric version of what people in the bush were doing. All these things that, you know, existed before. . . . My choice to look the way I do is just based on me relating to traditionally African aesthetic, but it was through punk initially that I had those senses reawakened.

Spooner’s documentary is in a lineage of black art speaking to the problem of representation. It is at once a rejoinder to images of blackness produced by a white gaze and an attempt to announce a uniquely black aesthetic.

The first Afropunk Festival took place in Brooklyn in 2005, birthed from the documentary and the online message boards that flourished in its wake.

The festival’s arrival in South Africa, the home of Sara Baartman, was a fitting return: a traveling showcase of black freaks, but on their own terms.

The purportedly radical politics of the festival were often in tension with its branding. In the crowded market set up by the organizers, I often felt an urge to resist the spectacle, to push against the official Afropunk logo, “We the people, believe in yourself,” which appeared on posters, clothing, and other branded items sold at the market. The slogan, encircled around two crossed fists, struck me as an out-of-place Americanism. “We the people,” the opening fragment from that duplicitous document, seemed especially out of place in a South Africa that has been confronting the hollowness of its own founding mythologies: jostled into consciousness by the students in the Rhodes Must Fall and Fees Must Fall movements, the country is currently being dared to destroy Brand South Africa and its accompanying icon, the depoliticized Mandela. The goal of these student revolutionaries is, as Leigh Ann Naidoo put it, to “annihilate the fantasy of the rainbow, the non-racial.”

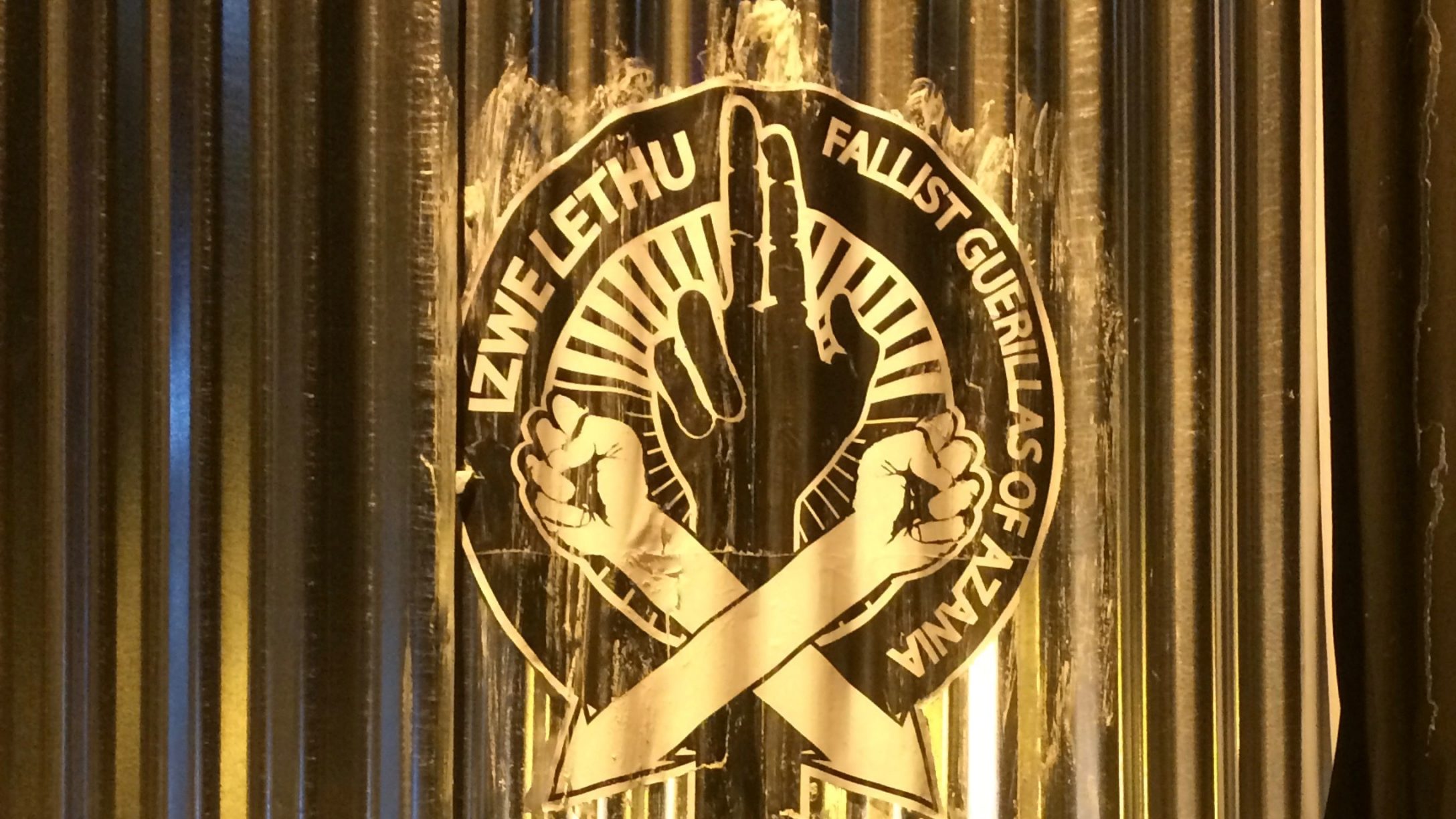

These challenges to South Africa’s post-racial branding, ironically, only worked to firm up Afropunk’s “all black everything” branding. In the early hours of 2018, following a performance by the American rapper, drummer, and singer Anderson .Paak, I followed other Afropunkers out of the grounds, feet throbbing after hours of being planted in the perfect spot we’d claimed earlier in the day, refusing to cede ground to bands of teens who elbowed our backs as they sweetly explained that they “just wanted to get closer to the stage.” I was in search of something sufficiently fatty to steady me after a few overpriced Millers. The large area where the food vendors were located was enclosed in a shiny corrugated-metal fence, giving the space a DIY, radical aesthetic. A series of black-and-white AFROPUNK posters were wheat-pasted onto the fence. Next to them was a solitary poster declaring “IZWE LETHU, FALLIST GUERILLAS OF AZANIA.” Fallists, as the student revolutionaries call themselves, tend to draw from the legacy of the Pan Africanist Congress, historically the radical counterpart of the ruling ANC.

Although I had a boerewors loaded with parmesan shavings in hand, for which I had stood in a very long line, I stopped and marveled at this piece of guerilla art. Had a radical disrupted and claimed the space with this political gesture, or had the organizers integrated this local piece of activist art to give the festival a sufficiently South African feel?

But it didn’t matter by whose hand the poster had been put up. The South African musicians who performed at the festival still drew out the living history of black resistance contained in the site. In a moving performance on the second night, the singer Thandiswa Mazwai reminded the crowd, as we stood pressed up against each other in the darkness, that we were on hallowed ground. Addressing the Americans in the crowd, she informed them that this was where many of South Africa’s “mothers and fathers” had been imprisoned. Mazwai went on to preface her performance with a reminder that “there are times when you need to throw stones.” Just a few months later, South Africa would spend weeks remembering and debating radicalism and resistance in the aftermath of Winnie Mandela’s death in April. Mazwai would again take to the stage at Constitution Hill for a concert held there in Mandela’s honor. A hashtag that circulated in the days immediately following Mandela’s death, #allblackandadoek, encouraged women to pay their respects to Mandela by replicating her iconic look. Fashion, nostalgia, and something like radical politics again collided as selfies of black women in bloodred lips, head wraps, and black outfits took over social media timelines. I arched and unarched an eyebrow when I read that the singer Simphiwe Dana had described her own funeral attire as “protest couture.”

For black people, often captured and archived without our consent, these practices of self-documentation can take on a special kind of significance. At events like Afropunk, people play at claiming and disavowing an authentic blackness. Sizing up each other’s carefully crafted looks, we meet each other’s eyes and confirm that ours is the only gaze that matters. (I see you, boo.) The recognizable nature of this costume became evident to me when, out to dinner the first night, a South African man seated at the next table leaned in and asked us how the festival was.

I asked how he knew that we were coming from Afropunk. “Come on,” he said, gesturing at us.

At times, Afropunk was awkwardly self-conscious, exposing itself as an event designed to cure the afflictions of black middle-class identity. But still, it was nice to see and be seen in context. On the first day of the festival, an hour before we caught an Uber to Constitution Hill, I watched the British supermodel Jourdan Dunn, dressed in a matching purple crop top and shorts, her hair cut in a bob, walk into the fast food chain Nando’s at a nearby mall. Seated at a booth by the register, my friend and I, in awe, quietly debated asking her for a picture. We ultimately decided against it. This very famous black woman, regularly photographed, scrutinized, and objectified, had the privilege of anonymity for a little while. Since we didn’t get photographic evidence of our sighting, a moment for the ’gram, we settled for this: If Jourdan Dunn was here with us, then we were in the right place. Let her eat the official chicken of the postcolony in peace.