What Laurin Stennis proposes is eminently reasonable.

“We’re trying very hard to offer a safe median, approachable from any direction,” Stennis, a visual artist in her forties, tells me over coffee in Jackson, Mississippi. “No questions asked, no judgments. Truly bipartisan, grassroots, and positive. An honest, calm, positive spirit of intention can go a long way.”

So she hopes. Stennis has directed her mindfulness to a volatile matter: changing the Mississippi state flag, which reproduces the Confederate battle flag in its upper left section. First flown in 1894, it’s the last state flag in the US to flaunt the symbol of secession and the war for slavery.

The flag is a problem. Mississippians know this, but many don’t mind. In 2001, a commission proposed a new design. It swapped out the rebel flag and replaced it with 20 white stars on a blue background—Mississippi was the 20th state to join the union—leaving the rest unaltered. In a referendum, 64 percent of voters rejected the change.

Three years ago, Dylann Roof committed mass murder at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina. Images surfaced of Roof paying homage to Confederate soldiers and flaunting the Confederate battle flag, and for a moment at least, something shifted. Confederate statues and other public memorials began coming down. According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, which recently released its latest tally, 110 “public symbols of the Confederacy” have been removed since the Charleston massacre—though the group notes some 1,728 remain in place.

Each removal is a big deal. Some came through direct action, as when Bree Newsome scaled the flagpole in Columbia, South Carolina, in 2015, or when protesters pulled down the statue of a Confederate soldier in Durham, North Carolina, in 2017. Others followed months of debate in city councils and commissions, and acrimonious public hearings. In Memphis, Tennessee, a state law forbade removing monuments from public property, so the city government found a loophole: it sold the two parks hosting statues of Jefferson Davis and Nathan Bedford Forrest to a recently created nonprofit on December 20, 2017, and workers removed the statues the same night. And in New Orleans, after shepherding the removal of four Confederate statues, then-Mayor Mitch Landrieu gave an eloquent speech last year that hoisted him, according to some pundits, into the ranks of presidential contenders.

This new tide has reached Mississippi, where even some in the Republican leadership sense that the state may be missing the moment—and jeopardizing future investments, conventions, and tourist revenues. Philip Gunn, the House speaker, was first to go out on a limb. “As a Christian, I believe our state’s flag has become a point of offense that needs to be removed,” he said after the Charleston horror. Various bills have been introduced to replace the flag, or to add a second flag with “equal status and dignity.” “The flag is going to change. We can deal with it now or leave for future generations to address,” Gunn said in 2016. So far, all the bills have died in committee.

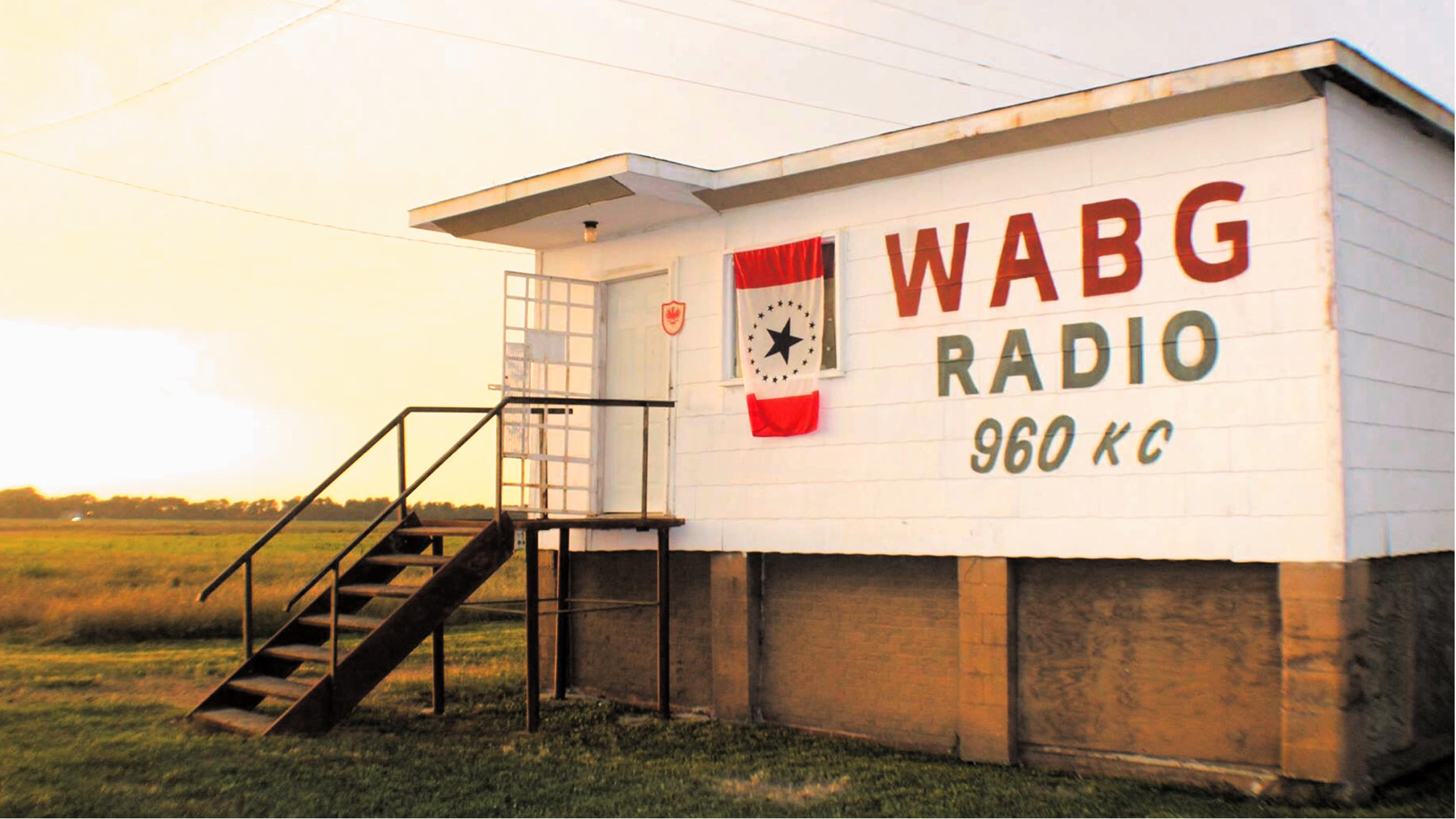

Stennis has an alternative. Various new designs for the state flag have been floated, but only hers has gotten traction. It has appeared on bumper stickers, in front of houses in the genteel Belhaven neighborhood of Jackson, and in the front window of Steve’s, a popular downtown lunch spot near Jackson City Hall. It’s on sale—as is the official one—at A Complete Flag Source, the big store off I-55. There’s a community group: the Stennis Flag Flyers.

(Image courtesy of Siddhartha Mitter. Jackson, MS.)

(Image courtesy of Siddhartha Mitter. Jackson, MS.) (Image courtesy of James Poe. Greenwood, MS.)

(Image courtesy of James Poe. Greenwood, MS.) (Image courtesy of Michael Boykin. Natchez, MS.)

(Image courtesy of Michael Boykin. Natchez, MS.) (Image courtesy of Gwen Trigg. Collins, MS.)

(Image courtesy of Gwen Trigg. Collins, MS.)Her design is prudent, even conservative. She dove into vexillology—the study of flags—and checked her colors and layout with experts in the field. The flag has a broad white field with 19 small blue stars in a circle and a large 20th star in the middle—again, invoking Mississippi’s order in joining the union. There are two thin, vertical red bars, at the left and right edge. These, Stennis says, acknowledge the state’s history of division and bloodshed, but in a philosophical way, open ended.

Stennis called her initiative “Mississippi I Declare.” “It was clumsy and such,” she says. One day, a state legislator told her everyone was simply calling it the Stennis Flag.

“It was never my intention for the flag to have my name as its moniker,” she says. But her name carried weight. Her grandfather was US Senator John C. Stennis, a giant of twentieth-century Mississippi politics who served in the US Senate from 1947 to 1989. An old-school Dixiecrat, he supported segregation, then mellowed late in his career, supporting the extension of the Voting Rights Act in 1982 and endorsing some Black political candidates. He died in 1995; his name now graces a NASA rocket site and a Nimitz-class aircraft carrier.

Stennis lives with this memory—the affection for her Pawpaw, the anger at his role in history. “The name Stennis does still have some recognition in the state, and my family’s narrative and evolution may lend some credence to the effort,” she says. “I don’t know.”

She’s attracted support—for instance, from columnists Billy Watkins, in the Clarion-Ledger, Ben Williams, in the Mississippi Business Journal, and Saizan Owen, in the Jackson Free Press. By her own estimate, most of the people who’ve adopted her flag have been white Mississippians. But two Black state representatives, Sonya Williams-Barnes of Harrison County and Kathy Sykes of Hinds County, have each introduced a bill to adopt her design.

So far, no dice. But the flag question in Mississippi is not permanently congealed. Between 2015 and 2016, all eight public universities in the state removed the official flag from their grounds. In Hattiesburg, Columbus, Oxford, and Clarksdale, among other main towns, the flag no longer flies on municipal property. The same is true in Jackson, the capital, where four out of five residents are Black, though you still can’t avoid it at state buildings, such as the Capitol or the Governor’s Mansion.

In other towns, a battle is underway, shaped by the particularities of municipal government and local politics. In Pontotoc, for instance, the mayor ordered the flag taken down, but the aldermen overruled him. In Tupelo, the flag flies at some municipal sites but not at the police station; the city council ordered it flown there, but the mayor reversed the order. In Ocean Springs, a group of residents and nonprofits has sued the city to take the flag down: they argue its display violates the Fair Housing Act and the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Amid this antagonism, what space is left for a deliberately moderate, consensus-seeking initiative like Stennis’s? The mood of national politics under Trump doesn’t help. Stennis is realistic about the obstacles. “With gerrymandering, our state has created a system that equates ideology and party with race,” she says. “It’s not conducive to thoughtful discussion.”

In Mississippi, like everywhere else, politics are fluid. Following the retirement announcement of US Senator Thad Cochran, both Senate seats are up for election this year. The flag may feature in this year’s statewide political battles. Or it may not; there are so many other problems to deal with.

Stennis believes better vibes are in reach. Hers is an old-fashioned civic faith, all reasonableness and common purpose. It feels out of step with the national moment, but as her design finds adherents, she takes heart.

“Now that there is a symbol, we’re becoming visible,” she says. “The possibility starts to come alive. It feels good to share a positive symbol, to wave to one another. Who knew that a state flag could actually be fun?”

(Image courtesy of Frank Farmer. Hattiesburg, MS.)

(Image courtesy of Frank Farmer. Hattiesburg, MS.)