The happiest moment of my childhood was in the mid-1980s, when my parents heard that Saddam Hussein had been shot and killed at a political rally. The whole family gathered, jumping up and down and holding hands, as though dementedly dancing around an invisible Christmas tree.

This manic elation was punctured minutes later. The radio broadcast had been wrong: Saddam was still alive.

By this point my parents were living in Stockholm and had recently become Swedish citizens. Yet, far as we were from Iraq, Saddam Hussein was a bogeyman that haunted us. My parents explained why they had fled their home country and could not return by describing his horrific acts against Kurds, how family members I would never meet had been arrested and killed back home, a home I had never been to. I blamed every incomprehensible mood swing and outpouring of emotion on this one man, intermittently seen on the TV grinning as news anchors tiptoed around his regime’s brutality. We were Kurdish activists, as all Kurds were then; when we weren’t traveling across Sweden to demonstrate in front of whichever embassy had ignored our plight that week, we spent the weekends going from one immigrant-heavy Stockholm suburb to the next, attending other people’s wakes. We chanted non-rhyming slogans like Saddam! Fascist! Murderer! until we lost our voices; in snippets, we mused on his methods of torture when other Kurdish refugees gathered in our home. Rape with a broken bottle, electric drills inserted into orifices; it all seemed so needlessly brutal that I couldn’t process it.

Perhaps inevitably, he would forever be more myth than man to me. After the horrific 1988 chemical bombing of Halabja, where over 5,000 people were killed, my parents sent out leaflets with photographs of the victims, horrific pictures of dead children, their skin discolored, their eyes open and blank. For months these images were scattered across our apartment, traumatizing both me and my sister. This, too, was something Saddam had done.

From an early age, I was well aware that but for a stroke of luck, Saddam would have led to me not being born at all. In 1980, my parents had gone to a political meeting in West Berlin while my mother was pregnant with me, a meeting that was being targeted by the Iraqi embassy in East Berlin. A man was to bring a briefcase filled with explosives to the Kurdish meeting; instead, he had a change of heart and informed various intelligence agencies, sparing the lives of the hundreds of Kurds from all across Europe who had gathered there. I was born.

We waited for his death as a family. In anticipation of the celebration to come, my father bought a bottle of Royal Salute whiskey to be opened only when Saddam was truly gone. When the first Gulf War instilled a sense amongst us exiled Kurds that Saddam’s days were finally numbered, my parents told me and my sister that the day he died, we wouldn’t have to go school. If I hadn’t wished for this ogre to be vanquished before, I certainly did now.

And yet, I became surprisingly protective of my dictator. I was not insulted at the post–Gulf War portrayal of him as a preening dolt in movies like Hot Shots Part Deux, which minimized his regime of terror for cheap laughs; I felt glee that my baddie was being represented in a big blockbuster movie. Just as children argue over whether Spider-Man could beat Batman in a fight, I argued with a Chilean whose family had escaped Pinochet’s brutal rule over whose dictator was worse: Augusto may have had dissidents shot, but did he set rabid dogs on political prisoners while their children were made to applaud at gunpoint? Turkmenistan’s Saparmurat Niyazov may have renamed the months of the year after his family members and interrupted parliamentary sessions to read new poems he had written, but had he once banned white socks? Or written lurid romance novels under a female pseudonym? Or based his secret-service uniform on Darth Vader’s helmet? Or been obsessed with the TV adaptation of Little House on the Prairie?

When I found a rare English translation of Saddam’s Revolution and National Education, a collection of speeches he gave in the 1970s, I cackled at the editor’s footnotes wherein Saddam was referred to as “comrade Saddam Hussein.” My fear was like fandom: arcane knowledge, the purchase of rare totems, and a need to argue for his status as the worst.

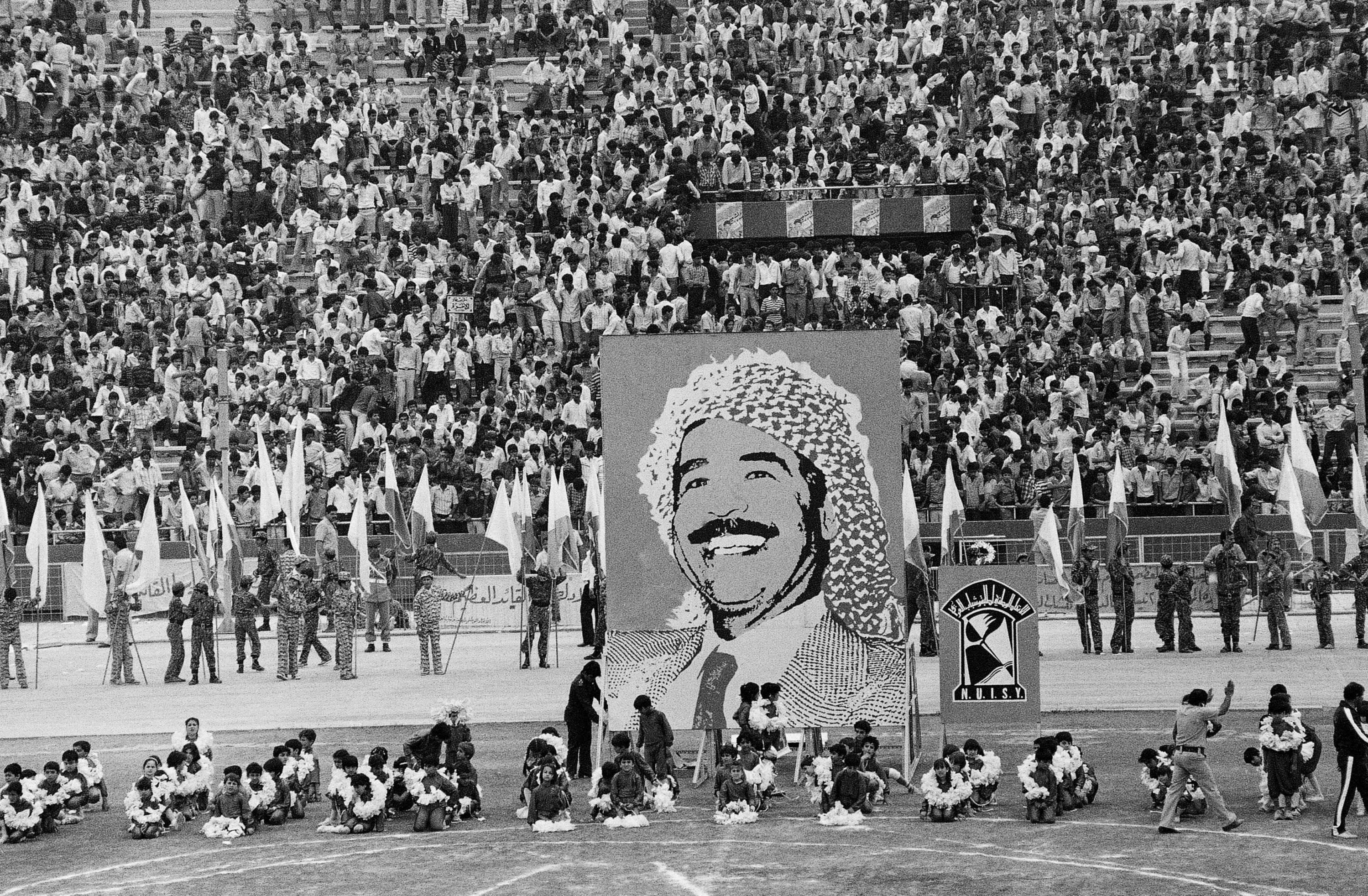

Saddam’s cult of personality infected us in exile. In Iraq, of course, he was everywhere: his garish portraits littered every corner, and he even had a proto–reality show in which he would disguise himself and visit a factory and ask what people thought of him (only to reveal himself at the end). In all the discussions of Iraq’s crimes, no name but Saddam Hussein’s was ever mentioned. It was never Iraq, nor even the Ba’ath Party; it was only Saddam. So when the rest of the world was demonstrating against the increasingly inevitable 2003 invasion, we Kurds were baffled by this sudden outpouring of pacifism; where were you when we were getting killed? If the upcoming war was against Saddam himself—and there was only Saddam—how could such a war be unjust?

Christopher Hitchens once told the story of a man at a Baghdad teahouse who spilled his drink on a newspaper featuring—as it always did—a photograph of Saddam Hussein; if the wrong person in the café had witnessed this act, he said, his days would be numbered. Hitchens’s description of the man’s sheer terror may seem like an exaggeration, but let’s not forget: at Saddam’s first party conference after taking power in 1979, he made half the high-ranking members of his party shoot the other half, arbitrarily accusing them of treason. That was his first day on the job, well before the special mass graves he dug for children who had their eyes gouged out, or the installation of a secret torture chamber inside the Iraqi embassy in New York. Who can say what level of paranoia was appropriate?

To construct a cult of personality, as Saddam so conspicuously did, requires a porousness in the borders between fact and fiction. Saddam encouraged notions of himself as a larger-than-life character to be dispersed amongst his subjects (and the world at large). This makes it more difficult than usual to assess what, of the above, is actually true. There is no online record of an assassination attempt against Saddam, even though it is one of my most vivid memories; the only reference I can find is the attempt in the city of Dujail, in 1982, which I would have been far too young to remember. That Saddam was obsessed with Little House on the Prairie is Iraqi lore, asserted as fact by the National Enquirer (in 1991) and cautiously repeated by the London Review of Books (in 2012). As for the fact that white socks were once used as an excuse to round up Kurdish dissidents in the city of Suleymaniye, I can find no proof and have to rely on anecdotes told to me by family members. If this uncertainty was of Saddam’s own design, it was also the result of a traumatized people’s attempts to put logic into the chaos of his brutality.

When the bogeyman was overthrown, statues were toppled and US stores sold toilet paper printed with his face and the slogan “Wipe your crack with the guy from Iraq.” Imagery that Saddam had used to his advantage was now being used against him; as the War on Terror shifted from Afghanistan—“not a target-rich environment” according to Rumsfeld—Iraq turned out to be a country ripe for iconoclastic acts. When Saddam was finally located in an underground bunker, he looked like a crazed hermit, and footage of his checkup and delousing replaced all the news footage of him shooting a gold-plated Kalashnikov or firing off a rifle one-handed wearing a hat that looked like a recumbent ferret. When he was executed, Fox News showed the blurry phone recording of his hanging and followed it up with a side-by-side picture comparison: one an old photo from his arrest, marked “Alive,” the other a still from after the execution, labeled “Dead.”

The bogeyman is no more. But my perverse fascination with him persists: a chance sighting in a Kurdish restaurant of the judge who presided over Saddam’s trial led me and my cousins to exchange the kind of excited whispers you’d expect for pop stars. I have watched the 2008 BBC/HBO miniseries House of Saddam more times than is reasonable and have not only pored over his (deliciously terrible) novel Zabibah and the King, but followed the disagreement within the CIA—which studied the novel when it came out in 2001 for insight into the mind of their soon-to-be enemy—as to whether he wrote it himself or not.

The day he was captured, in December of 2003, my mother woke me up to tell me the news. I was on winter break from university, visiting my parents; I had been out the night before, drinking with high school friends. Still slightly hung over, I was unable to process the information I was being given. I had been expecting, or hoping for, his death. I never imagined he would ever be captured alive (a sentiment I shared with the US government, according to former CIA analyst John Nixon, who debriefed Saddam after his capture). But as I made my way to the living room and it sank in that Saddam Hussein Abd al-Majid al-Tikriti was indeed being held by US forces, there was no trace of the sense of elation I had felt as a child. Instead, I felt angry: the day he is caught, I have no school to skip! We couldn’t fulfill the promise my parents had made to me, decades ago; we couldn’t find the bottle of whiskey my father had bought to prepare for the occasion. My sister, still in school, had a midterm she could not miss.

He couldn’t even let us have our moment, the bastard.

***

“My Dictator” is a regular Popula column exploring the afterlives of political leaders who don’t go when we tell them to go, lingering on in our minds and identities long after their terms are expired.