In the four years I’ve been a used-book buyer, I have touched about nine spiders. Mostly I come across their stiff and abandoned egg sacs, which tend to line the edges of books that have been sitting too long in someone’s garage. I have been offered a box which contained a length of stained gauze, several rather large rocks, as well as many forms of media that I politely decline to look at: the VHS porn tapes which, somehow, never belong to the seller, boarding passes, postcards, shopping lists, and even love letters. I especially enjoy the carefully written index cards detailing a novel’s family trees, diminutives, or murder victims. But my coworker once found a syringe. You can guess, but until you get in there and riffle about, you’ll never know.

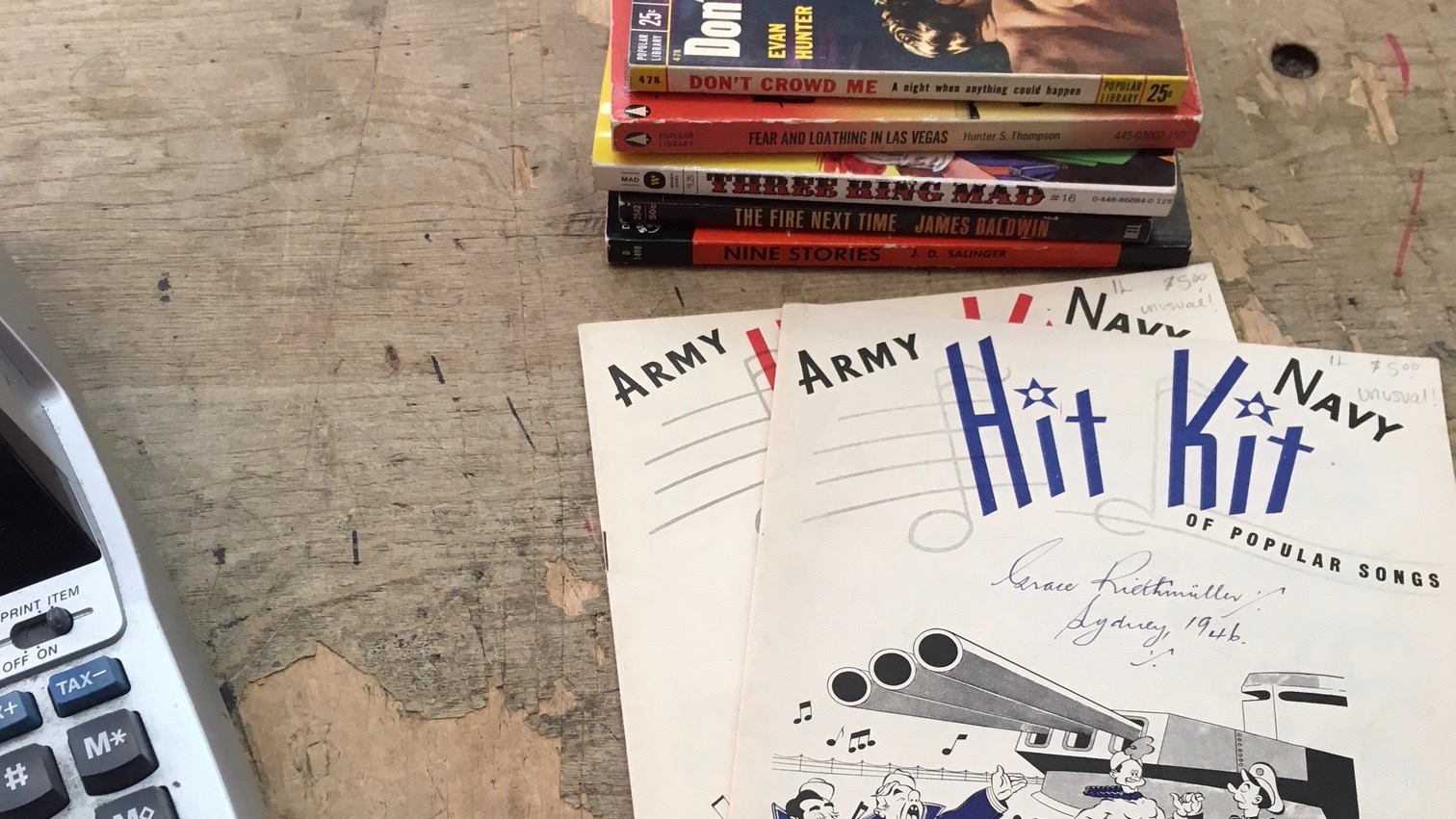

Books come to me in cardboard boxes, paper bags, reusable totes, children’s organizational cubes, rattan baskets, and plastic bins. These are all a welcome sight; the books will tend to be recently purchased and in reasonable condition. What I dread are the decrepit cardboard boxes or trash bags. Books schlepped in a rippling thirty-gallon plastic bag are not books in reasonable condition; they are books which have become recyclables or a mold hazard. And yet occasionally there are treasures: the first time I ever saw an Armed Services Edition paperback it was in a trash bag. There were fistfuls of them, binding and pages all perfectly intact (despite the former being a single staple and the latter incredibly thin and delicate). I bought them all and watched them sell within days.

My rules for buying are as follows: Be picky. Be fair. Don’t go against your gut. Always check stock. And don’t spend the store’s money badly to make someone feel better.

When I consider a book, I smooth my palms across the cover and back, run my fingers along the edge of the pages, and I jostle off the dust jacket to check for food stained boards. I flip through several times, looking for marginalia, and check whether the spine can keep holding or will crack. You must check the stubbornness of stickers: if they are unyielding at first, they are typically not worth the time it will take to coax them off, slowly, in delicate and infuriating tendrils using a small plastic tool, rubbing alcohol (for the paper) and lighter fluid (to dissolve the stickiness). That’s the thing about most books in less-than-desirable condition: you needn’t buy them. Another copy—a better copy—will come.

Far and away my busiest buying day is Saturday. After opening the store in the morning—which I do briskly, always in the same order, and typically with my morning song of choice “Broken English” by Marianne Faithfull playing—my day is largely repeating the phrases:

“It’ll take about 10 minutes, you can look around.” (Hollering slightly) “I’M DONE WITH YOUR BOOKS!” And, often, “I’m sorry, there’s nothing we can use today.”

Once, a particularly cantankerous older fellow answered back at me, “Well then what about tomorrow?” a bit more saucily than the situation called for. “Well, bring in different books tomorrow and we’ll see,” I responded. He chortled. Guys like that always chortle.

Anyway. Many of the books I look at are perfectly fine, and yet I do not buy most of them. It’s not a brushoff! There’s no amount of selling power that can move a book people no longer want, or (even worse) eight copies of that book. A book languishing on the shelf means I made a poor choice as a buyer. It’s a maddening feeling. Some are simply past their time; people don’t typically care to revisit a 1997 bestseller. Some we’re just sick of seeing. It’s difficult to explain, but in the eight years I’ve been a bookseller, my book ESP has grown strong and accurate.

Of course, I have been known to take in some… shall we say… questionable materials. I firmly believe our sale cart needed a $4 copy of Jane Seymour’s iconic Guide to Romantic Living. And I have folded many a Mylar cover onto shabby-but-charming hardcover jackets, hoping the right person will see what I saw. Selling books is a matter of the heart, and it’s difficult to explain the alchemy, the weird luck, involved in what I do. Like when I found a pristine copy of an out-of-print poetry book that—when I was fifteen, and deeply in love with it—I stole from my Mom and have held captive ever since, despite her gentle scolding. Or a business card from Momofuku, tucked in a novel, with “tell her about the dream” scrawled in cramped ball point on the back.

Sometimes customers present me with credit slips written in the distinct, bold hand of a coworker who passed away several years ago.

Used bookstores hold this tension with the past and present: what was once new becomes old, and what was old becomes new again. And so, each Saturday morning, my key’s in the lock (push, then turn for the top, pull then push for the bottom); I quiet our alarm; I wake up our computers, and I listen to my Marianne Faithfull song. I finesse our temperamental safe into opening and fix myself a cup of tea. I say quietly, “Good morning, store. I’m happy to be here. I hope there’s good books today.” I put out the newspapers, drag library carts full of discounted books to the sidewalk, plug in the neon sign. I open the doors for whatever titles will come through them, some for the first time and some for the tenth.