I. I CAN READ, I CAN’T READ

Last October I started watching American football. I was at a writing residency. I had a month alone in a fishing boat in the forest on the side of a mountain in Canada. I’d grown up nearby, but I didn’t know anyone anymore. I was trying to make the novel I was writing mean something. I was disintegrating in the ragestorm of #MeToo and #TimesUp. I was exercising with hypoxic viciousness. On a Saturday afternoon, I turned on the TV and watched Louisiana State cling to a one-point lead over Florida through the fourth quarter. “So long from the swamp!” chortled the commentator at the end. I was writing sex scenes that ended with men getting murdered. I was trying to read Arendt and Foucault. I watched LSU beat Auburn the next week. I was chaste but very vain. The novel I was writing had begun to feel like something I was guilty of. I watched the New Orleans Saints beat the Lions, the Packers, the Bears, and the Bucs. Football was intricate and inscrutable. It titillated me. I couldn’t read it. I was illiterate. This was soothing. It was like being loved.

I am seduced by my own meagre capacity to be, to merely absorb or refract. I turn into a muteness.

—Lisa Robertson, “Lastingness: Réage, Lucrèce, Arendt”

Lisa Robertson describes reading like it’s a sexual submission. She talks about submitting to invisibility. Lathe biosas, Epicurus advised his Epicureans: live in hiding, or maybe, live unknown. Whatever happens to her while she reads, no one can see it. Reading does not produce predictable results. Even the most authoritarian author can’t control the effects of their writing on the reader. Readers become conduits, or slaves, and follow along not knowing where they’ll end or what they’ll become. “This is a pleasure,” Robertson says.

Robertson also says that while will is one of reading’s requirements, passivity is equally necessary. The text masters us with strictures and codes, and we desire these rules as much as the text’s promiscuous potential. We desire the text. When we annihilate ourselves in it, we do so deliberately: we are complicit. The text is like porn: it’s not important whether it desires us. But I want it to.

In my boat on the mountain, submitting to football—“Football?” friends said—was more pleasurable than my other reading. It required almost nothing of me. It produced very little angst, but it was not unemotional. Obviously it was exciting. I was innocent of its meanings. I was not responsible.

I tried to explain it. I typed: “Watching it is calming like reading experimental poetry is calming, once I just let go of trying to understand anything.”

I was typing at the jock I’d been banging, cynically, back home. “No,” he said. “I want you to be able to tell what a cover 3 defense is by the time you come back.”

Of course there is a man involved. I don’t even like the Olympics. Is the word jock pejorative? This man makes his living writing football analysis, coaching a college team, and writing football jokes on Twitter; in the rec league season, he plays on three different flag teams. For a few months, his name in my phone was two football emojis. Louisiana State is his team; so are the Saints.

It’s convenient for my aesthetic that the Saints, in their black and gold, are the health goths of the NFL: they built their stadium on top of a cemetery, and in 2000 they hired Ava Kay Jones, a Voodoo and Yoruba priestess, to lift the resulting curse by draping a boa constrictor around her neck at midfield before a game against the St. Louis Rams. They won that game: their first-ever playoff win. They also won the first eight games I watched.

“You’ve never seen them lose,” the jock said, vexed. He is an unusually silent person.

Robertson says texts seek, in the complicitous, quiet minds of their readers, traces of other texts’ passage. “The effect is the inflation and complication of a taste for ambivalence . . . for a text that embodies its own refusals.”

As always, I’m at risk of conflating my desire with my desirability. If I pretend that my wants line up with what patriarchy wants, I’m no longer its victim. Male friends confess to me that they watch football to be close to other men. The tenderness of virile men has always been the booby prize of patriarchy. Every feminist measures the amount of time she spends watching men do things against the time she spends doing things herself. When my ratio skews, I prefer that it happen not out of fond acquiescence, but curiosity. I recognize this flare of excitement: it signals work and begs reconnoitering. It’s called, embarrassingly, inspiration.

I’m reading this text because it finds no other text to speak to in me.

At first there are two things to read in televised football: the gestures of the players and the language of the commentators. Instead of a rightward stream of letters: colorfully spandexed action figures scramble chaotically as male voices twang singsong nonsense; interspersed with images of various stoic male emotions; interspersed with intimate, abstract, slow-motion images of male bodies performing beautiful or violent feats; interspersed with blaring odes to pickup trucks. And hamburgers.

Sometime in November, Saints corner Marshon Lattimore—who was later named defensive rookie of the year—picked off Falcons quarterback Matt Ryan. There were several slow-motion replays. Gifs proliferated. Not because it’s so rare to intercept a pass, but because Lattimore didn’t touch the ball with anything but his butt. (He had dived, the ball was deflected onto him, it didn’t fall off.) This is how I learn what an interception is, and how to syntactically navigate the verb to pick off.

This text has many codes and strictures. I have to learn vocabulary, rules, metadata, strategy, statistics, technique, names, history, politics, scandals. In order to stir my own emotions I need a context that can hold a narrative. I kept my phone at hand. My search history documents my halting descent into the mise en abyme:

conversion in football

2 point conversion

what is a pass rusher

man-to-man defense

coverage in football

cover 3 defense

how many black quarterbacks in the nfl

racism in football positions statistics

bountygate

deflategate

is tom brady’s hair real

zone read

what quarterbacks read in zone coverage

power read

inverted veer

drew brees holding a baby

drew brees holding a baby

drew brees holding a baby

II. NARRATIVE IS CORRUPT AND ABSOLUTE NARRATIVE CORRUPTS ABSOLUTELY

After I left my boat in the mountains, work on my novel ceased. I was living off the dregs of a grant for my first book. I read two anthologies of New Narrative, a San Francisco scene of queer, feminist writers, influenced heavily by theory and the language poets, who created a confessional form that used their friends’ real names and a lot of explicit sex. I also read nonfiction by straight white men: Friday Night Lights, The Blind Side, Reading Football, Against Football. Annoyed with janky pirate streams, I paid 20 dollars a month to a streaming service called DAZN (pronounced, of course, “Da Zone”). I paid 13 dollars a month to go to the gargantuan 24-hour gym around the corner from my apartment, where I scurried upstairs to the empty women’s section—Fit 4 Femmes—where no men could watch me deadlift. My pipes froze twice. “My friend says I’ve been playing like shit since I fell in love,” the jock said one night, offhand. I put his name alongside the football emojis in my phone. By January, #TimesUp was in full swing, and the ex I’d avoided for two and a half years emailed me a vague apology and some of the money he owed me. There were rumors a journalist was working on an article about him. I ordered a Saints cap with a golden fleur-de-lis on it but couldn’t make myself wear it in public, because I live in Montreal but don’t speak fluent French, because I’m not from New Orleans, because I’ve never worn baseball hats so they make my head look weird, because when people talk to me about football I blush. Still, I wore it around the house, smoking on my balcony, folding laundry. Wearing it, I felt safe.

A sentence is an interval in which there is finally forward and back. A sentence is an interval during which if there is difficulty they will do away with it. A sentence is a part of the way when they wish to be secure.

—Gertrude Stein

Football is described using monosyllabic Anglo-Saxon nouns, which are often used interchangeably as verbs: screen, run, slant, pick, pocket, pass, tackle, block, down, zone, rush. Football writers make sentences rife with parataxis and polysemy, sentences so torqued with ambiguity that they are meaningless to me. The jock’s Twitter reads like:

When the RB motions out, the space between inside backers becomes very wide

You end up with your Will against a quick slot receiver.

is 4 verts now just seams with automatic comebacks?

The strong safety cuts the trapper to box the run but the playside backer comes inside the puller (like he’s trying to spill it) and there’s a big crease for Love.

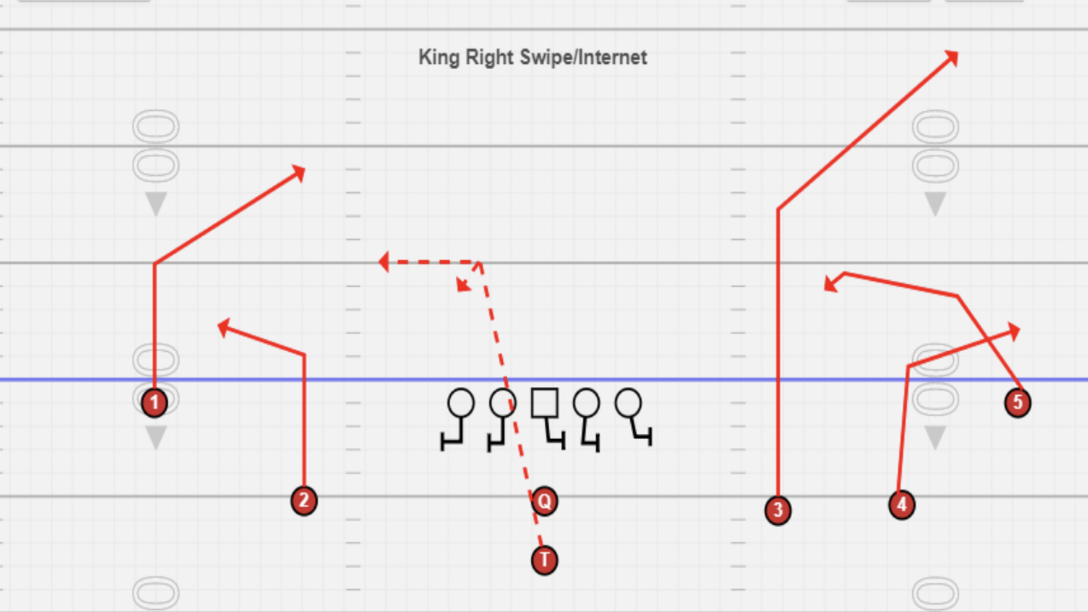

Meanwhile, play diagrams may as well be concrete poems:

Football language exists to describe the body’s gestures, but it begs a billion meanings. Even when I look up the words, the syntax boggles. Post-referential language—like language poet Ron Silliman’s “new sentence,” Derrida’s indeterminacy, Merleau-Ponty’s langage conquérant—is language so ambiguous and unfamiliar that it startles us out of ourselves. Attention catches on the words. As potential meanings multiply, we acknowledge that language doesn’t provide direct access to anything. Silliman calls realism a delusion.

I write realist fiction. Doors open and close, people look around. I’m embarrassed when I read prose to an audience, forcing imaginations into syllogistic chain gangs, the reader more slave than conduit. I’m embarrassed by the flattened meanings I’m imposing with my transparency: sculpted, framed off, unambiguous, mandatory. Pass/fail. If the language poets are right and ideology is the imaginary resolution of real contradictions, then narrative, lately, has started to seem totalitarian. I hesitate. Who am I to decide which details to include, which to excise?

The first draft of this essay was a short story. I had to abandon it, I couldn’t write the sentences. That was the first problem. The second problem, the insurmountable one, was the narrative.

According to Michael Oriard, offensive lineman turned academic and author of Reading Football, each play in football is a narrative drama. The game is a cultural text with metaphoric content and social context, and each play is a mythology. Is manifest destiny and westward expansion. Is corporate America’s myth of scientific, rational, purposeful work. Is the last bastion of virtuous gladiatorial masculinity in a bureaucratized age. Is an expression of Anglo-Saxon strength and morality. Each play is a chess stratagem. Is a battle in an eternal war.

According to Heywood Broun, each play in football is a short story. “First come the signals of the quarterback. This is the preliminary exposition. Then the plot thickens, action becomes intense and a climax is reached.”

Or maybe football is a novel: intense burst of action, reflective lull, action, lull, action, lull. Narrative accumulates. Meaning jolts up through the sentences with all the relaxed flow of a traffic jam. Soon, I’m inching past the crash that caused it. I’m rubbernecking at the bodies.

Retired NFL players kill themselves and leave notes asking that their traumatized brains be dissected and studied. Women who report assault are reviled and harassed for ruining players’ careers. There has never been an openly gay NFL player. The American president called players “sons of bitches” for protesting racist police violence. College football players don’t get paid; 2 percent end up playing professionally, and the rest don’t always graduate. The NFL is the most lucrative sports league in the world, but football stadiums are generally funded by municipal taxpayers. The violence is not just on the field—the blood sport spans the spectrum.

And on the field? Players get hit and they don’t stand up. Commentators cluck solemnly as men are strapped to boards, loaded into golf carts, driven off camera: “We all know the risks, but boy, you just hate to see it happen.”

III. MY BODY, MY FRIEND

I took remedial gym class in high school. We had to run around a field, but I stepped on my crush’s shoelace and the whole herd of us tangled at the feet of the girls’ baseball team. The year prior I’d concussed myself on a sidewalk during a light jog. The word basketball summons a sense memory of a rough orange planet mashing my glasses off my face. Volleyball: disappointing a popular girl with my inadequate bump. My grade-one report card: Paige needs to improve her ball skills. In my first month at university, the girls in my dorm needed extra players for their rec flag football team and mistook my height for athleticism. I was shocked, standing on the rainy Saturday-morning turf, to understand they needed me to do more than just stand there. I had to know something. Not just the rules, but where to run, how to catch, how to act in my agonizingly visible body.

Watching football, I catch only the most grandiose gestures. Usually I don’t know where the ball went until the replay. But the most important movements of the men on the field are tiny and imperceptible.

The quarterback makes his reads. That is, he reads the defense to see how they’ve read him and his offense. Players lie with their bodies; they fake, they misdirect, they aim to be misread, they want to appear to be reading something they’re not.

If the corners are looking at the quarterback they’re playing zone coverage, but if they’re looking at the receivers they’re playing man-to-man coverage, so they look at the quarterback, who reads them reading him and adjusts his play accordingly—but he’s wrong, they’re playing man, and he’s tricked and there is an incompletion, or an interception, or a sack. “It’s all about the eyes!” crow the commentators.

This is called disguise, I’m told, and an ounce of disguise is worth a pound of scheme. So what’s scheme? “A concept,” says the jock.

I’ve become less unnerved by his concision. I’ve become comfortable not seeking comfort in language. I’ve been reading men for so long that I’ve started to prefer men I can’t read. He gestures reliably, without disguise.

A man’s presence suggests what he is capable of doing to you or for you. . . . A woman’s presence defines what can and cannot be done to her. . . . One might simplify this by saying: men act and women appear.

—John Berger, Ways of Seeing

Football is obsessed with men’s bodies the way the rest of us are obsessed with women’s. There is endless data-mongering: statistical analyses, scouting reports, game tapes. Height, weight, arm length, hand size: everything but dick length is explicitly quantified in what Steve Almond, in Against Football, calls “a dire search for meaning.” Like Vogue allowing a size-12 woman on its cover, a starting quarterback under 6′2″ is news. I receive weekly injury reports in my inbox—not out of human concern, but because fantasy leagues want the information in order to gamble better.

The whole league is a fantasy league, a fantasy of an ideal body. Lacan’s mirror stage describes that moment when an infant first sees itself in a mirror. The fascination is narcissistic: there I am, whole and ideal, but I do not feel ideal. This, he says, is the beginning of anxiety, of alienation, of paranoia, and, later, of desire. I doubt we view ourselves as ideal for long, though. Very quickly we require another body to which we can compare our uncertain selves.

If I compiled every data point I collect in a day about how I appear—mirrors, photos, angled reflections in storefronts, comments from friends, comments from strangers, sheer force of imaginative will—I’d black the grid. Women know how to quantify ourselves: body mass index, dress size, waist-to-hip ratio, body fat percentage, facial symmetry. Yesterday I spent several minutes reading an article that wanted to categorize my ass shape into a letter: A, H, O, or V. Once a girl sobbed into my arms about her ex’s new lover: “But she’s a seven and I’m a nine!” I wiped her tears off my collarbone and wondered what number she’d assigned me, the coworker to whom she donated her “fat clothes.” Metrics include perfection like perfection is achievable, an idea that is both absurd and compelling. It’s impossible to objectively measure one’s own appearance, yet women know our appearances are measured constantly, and the score decides everything.

The 40-yard dash is the standard measure of a football player’s speed. There are two football fields between my apartment and the north edge of this island, and every time I run past them I wonder how fast I’d sprint such a tiny distance.

“There’s that 4.4 speed!” the jock calls at a teammate sauntering past us to collect a ball.

“Does he actually run a 4.4?” I ask.

“No one in Canada runs a 4.4,” he says.

All the numerists I’ve known have been male. Male runners obsessed with their splits, male writers with their word counts. Have I ever dated a man who hasn’t eventually, diffidently or casually, asked my bra size?

“If you played for me, I’d make you play safety.” The jock has repeatedly, only half-jokingly, suggested I try out for the women’s tackle team he coaches.

“Because I’m so emotionally secure?”

“No, ’cause you’re rangy, you’re a runner.”

I’ve never been called rangy before. I look it up to see if it’s a compliment. Then I look up what a safety is. I begin to pay special attention to Marcus Williams, the Saints’ rookie safety: 6′1″; 202 lbs; 32½″ arms; 9½″ hands. He runs the 40 in 4.56 seconds.

I want to welcome this objectification of male bodies as a satisfying gender reversal, but it’s not. Two-thirds of NFL players are Black, and none of the owners are, and two-thirds of the coaches aren’t. At the NFL scouting combine—an annual invitational camp for college players—young men, mostly Black, perform physical feats while old white men evaluate them. Then there’s the draft, where team administrations barter to select and pay for the bodies they want.

Once they’re in the league, bodies are distributed into position along race lines: quarterbacks are 80 percent white, wide receivers are 88 percent Black. Corners are 99.4 percent Black. Apologists talk around these statistics. It’s slow-twitch muscle fiber genetics. It’s common sense. They say some positions require thinking and some require speed, or aggression. Of course the NFL isn’t racist. At worst, they will allow, it suffers from mimicry, or groupthink.

There was a confusing moment in 2017, before I started watching, when the political left somehow became pro-football as the right boycotted it. It wasn’t violence that had Trump shaking his fist against the NFL—it was players protesting violence. Is it possible to support the players without supporting the league? To support the players, but not Tom Brady and his MAGA hat? Now, when some stranger on Twitter announces they won’t watch NFL football anymore it’s a toss-up as to whether they’re fed up with the authoritarian owners or the whining, entitled players.

When an athlete assaults a woman it is minimized or ignored (Ben Roethlisberger, 2009 and 2010; Jameis Winston, 2012; Frank Clark, 2014, etc.), unless there is incontrovertible evidence (Ray Rice, 2014). A player can also be made out to have assaulted a woman in order to punish him (Michael Bennett, 2018). In the blood sport, violence is a necessary evil. When a player speaks against it—for instance, state-sanctioned murder of Black men (Colin Kaepernick, 2016)—fans and owners are apoplectic. Some positions require thinking, some require aggression. Violence is a tool.

In May 2018, two seasons after Kaepernick began protesting during the national anthem, the NFL announced a new policy wherein players who take a knee will be subject to punishment, their teams subject to fines. Players are allowed, however, to remain in the locker room while the national anthem plays. Kaepernick, whose career interception rate is the second-best in NFL history, was replaced by the 49ers with a white quarterback who throws a lot more picks. Teams deny blacklisting him, but he didn’t play in 2017, and no one really believes he’ll play in 2018.

“We can’t have the inmates running the prison,” said Bob McNair, owner of the Houston Texans.

“It would be selfish on my part to look the other way,” Kaepernick said of his protest, as if unaware that he is not supposed to be looking anywhere. He is only there to be looked at.

Because of the inherent contagion of bodily movement, which makes the onlooker feel sympathetically in his own musculature the exertions he sees in somebody else’s musculature, the dancer is able to convey through movement the most intangible emotional experience.

—John Martin, The Dance

Alvin Kamara makes a spectacle of his elusiveness. He flew through his first professional season as the Saints’ running back. Defensemen slid off him, he hurdled corners and safeties like they’d knelt down for the purpose, like he was playing a different game than everyone else. He was so good even I could see it. At the end of the season, he was named offensive rookie of the year, meaning the Saints took home both offensive and defensive honors.

The jock sighs: “He’s—yeah, he’s special.” I am briefly touched by this sentimentality, until I learn that special, like athletic or explosive, is standard in the vocabulary.

Watching Kamara was like reliving Lacan’s mirror stage. His ideal body sparked euphoria, pride, envy, and anxiety. What do athletes feel? What do they think? Are they nervous? Are they ashamed when they fail? Or does it all blur out in flow-state focus? Cartesian dualists might say that the brain envies the body’s clarity. With such a reliable body, Kamara’s mind must be so clear.

Dance critic John Martin described the body’s movements as a universal language, translating desire and emotion across racial and cultural boundaries. We read the scene, and our bodies internally simulates the movements of the dancer, or tightrope walker, or athlete. Martin argued we feel not just their musculature but their emotion, as the two are inextricable. The visible body spreads an empathic contagion.

I can sprint and jump, so I can imagine both comfortably, even joyfully. But can I imagine what 300 pounds of muscle slamming my rib cage sideways feels like? No. Maybe. Can I imagine being African American in Trump’s America? What does it mean for white fans to internally simulate the bodies of Black athletes? Expanding a reader’s empathy has always been the strongest argument for fiction, but at what point does empathy become presumptuous, misguided, hubristic?

Of course I loved watching the spectacle of Alvin Kamara. His body does the thing that Black bodies are supposed to do. He is unambiguous, highly visible, and silent. Watching him, white bodies can feel Black joy without confronting, let alone taking responsibility for, Black suffering.

Empathy alone is not enough. Reading—sentences, bodies, statistics, scandals, any of it—is not enough.

IV. THE TENDERNESS

It’s June. The Saints fell out of the playoffs months ago. I canceled my DAZN subscription. The combine happened, the draft happened. My ex was named and fired. The jock has convinced me to join his softball team. My ball skills have not improved since first grade. I noodle the bat. The sense of being seen is like barometric pressure, humidity, bad weather. My senses are staticky, like my lizard brain is already working to black this memory out.

“You look delicate out there in the outfield,” the jock tells me.

I am momentarily flattered. No one has ever called me delicate before.

He says, “It’s ’cause you don’t know the stance yet.”

The stance? I learn the stance.

Reading is an experience, it is not a goal. Narrative will do things to you that you did not foresee or consent to. That is why rich white men prefer non-fiction.

—Madeleine Maillet, “Dusty Springfield”

Hannah Arendt notes that the opposite of the Epicurean lathe biosas is John Adams’s spectemur agendo. Let us be seen in action. Both edicts urge benevolence. Be good.

But what if, when I am looked at, it is seen that I am not good?

My editor calls to tell me—“How do I put this delicately, um”—that when I read my book aloud to an audience I give the impression of just wanting to get it over with. I’m cavalier, I don’t take the time to give appropriate weight to my words. He and my publisher have agreed that I need to fix this before they send me to any more events. “Is it embarrassment?” he asks. “Well, that’s easy enough to deal with.”

When the Saints fell out of the playoffs in January, it happened in the last play of the game. Marcus Williams—the rookie safety I’d been watching—mistimed a tackle so broadly that he didn’t even graze Stefon Diggs, allowing the Vikings a 61-yard touchdown with 10 seconds left. “I don’t know what happened,” Vikings linebacker Anthony Barr said. “I don’t know how it happened. I don’t know.” The whole travesty is listed on Wikipedia as the Minneapolis Miracle. I didn’t get up from my couch for an hour.

I feel for Williams. His embarrassment. How much did it hurt him to fail so publicly and catastrophically? And how will he convince himself that it won’t happen again? He thought he had control, but there is no control. He is the safety, but there is none. Can he play without confidence? He has to. Men act.

It’s been seven months since I’ve touched my novel. I can’t write it. Not because narrative is corrupt and gives me too much control, but because I don’t have enough. The fear is similar to my fear of writing about my ex: he’s threatened private investigations, defamation lawsuits. In Canada, the laws are on the defamed’s side: if sued I’d have to prove that my story is the correct one. Every selected detail must have evidence. I hear that in America it’s the other way around. If I speak clearly about anything I am liable. Transparency feels dangerous. I don’t speak, and I don’t write. But in doing so I’m not abdicating authority, I’m forfeiting agency.

Now this essay’s half-confessional. This isn’t New Narrative: I haven’t named names or detailed gory sex, but I’ve stated clearly that I am in love, so now you know how banal and female I am. I’ve written and rewritten, bloated and deflated, gone to rec league flag football games, read Mallarmé, Butler, and Derrida, watched Drew Brees’s Tide commercial three times. I’ve started over but excised the confessional, started over but put the sex back in, started over. I lack confidence. “You’re traumatized,” my women friends say. I’ve abandoned fiction, but I’m still a despot, hungry for that ideal body, the illusion of mastery. I’ve been trying to control how I appear, because I’m a woman and women appear. I’ve been trying to control how you will read me.

Lisa Robertson thinks that the pleasure of reading is in how we interiorize the text’s strictures, simultaneously subverting its power. I’ve read every man I’ve met: bosses and landlords, shitty hookups, cops and border guards. But it’s June 2018, and I’m no longer sure such a subtle complicity is worth differentiating, on my part, from outright collaboration.

Complicity with power is my urge to sit in the stands with a strong but useless body, to empathize with the body but ignore the mind. No, I really don’t want to stand out there on the field. I really don’t want you to read me, my bad thinking, my inadequate, failing gestures.

If reading has an effect, it’s a random one. Meaning filters up through the gaps. The gaze is reversed and flaws are exposed. No body is ideal. Select the details and bear the consequences. Your own text can’t love you back. This process is not soothing. It is embarrassing, incriminating, dangerous. It is necessary.

My softball team is all athletes. Some played growing up, some are killing time between other sports, a lot play for other teams too. They throw for miles, twist as they run, catch like their gloves are magnetized. They are encouraging and un-disappointed. “There you go!” they shout as I fuck up. “Good eye!” In the outfield, I stop a ball with my thighs and earn a cyclopean hematoma. I catch a sailing ball overhead and everyone—including the other team—is so happy for me it’s okay that I forget to throw it home. I’m embarrassed by their tenderness, which feels unwarranted. I love their tenderness.

The first time I hit the ball—a wobbly grounder straight at the pitcher’s ankles—I watched it for a second, then bolted. Thirty yards to first base is not far, just the length of my team’s dugout. Long enough to consider what they thought of my posture, for instance, or the supportiveness of my sports bra. I felt very tall. I was out. I scooted back to the dugout to be high-fived and hollered at like I’d run home. “There’s that 4.4 speed,” said the jock.