If you want to know what it feels like to be in Charlotte, North Carolina, you don’t need to go much farther than The Charlotte-Douglas International Airport (CLT). Not even the faux-homey rocking chairs—originally part of an in-terminal art exhibit about sitting on the porch—can prevent CLT from feeling like a mall. Indeed, big hub airports like CLT basically are shopping malls: bland corporate spaces with terrazzo floors and mid-to-upscale brand shopping in the foreground as always-armed security guards, slide into the background.

CLT epitomizes this: there’s a Johnston & Murphy, a bazillion Starbucks (but no Dunkin Donuts or local coffee brands), a Pinkberry, and a Bacardi-branded bar. You might think the hip-looking new restaurant in the main atrium, 1897 Market, is named after a significant date in local history, but you’d be wrong: it’s named after the year the Maryland-based highway-and-airport convenience store chain HMSHost was founded. The few local businesses are all big brands, like Bojangle’s and NASCAR, and the only break in the mallscape comes from the Black women who make up the majority of the food service workers, and whose hair and makeup are often creatively non-corporate. As the recent incident at Duke University shows, the state’s white leaders aren’t especially comfortable with the presence of Black culture in their bland spaces (though they do seem to love Bojangle’s).

Charlotte prefers redevelopment to historical preservation. Despite being founded in the eighteenth century—and having declared independence from Britain in 1775, even before Hancock and friends did—most of the buildings in Uptown (i.e., downtown) Charlotte are straight out of the 1980s or later; there’s barely any brutalism left, let alone pre-war architecture. Mid-century modern might be hot right now, but developers are razing it to make room for more generic retail. Even hip neighborhoods simply replicate the craft breweries and farm-to-table restaurants that you find, like pieces of flair, all over the globe. There haven’t been any art galleries in the so-called “arts district” for a decade, and at least four major mid-sized independent music venues have closed due to gentrification and development—though Amos’s, is reopening and Crown Station relocated—while the Live Nation owned NC Music Factory expands. Charlotte’s most legendary and most crusty music venue The Milestone has survived (with the help of crowdfunding), preventing CLT from doing to it what EWR did to punk club CBGB.

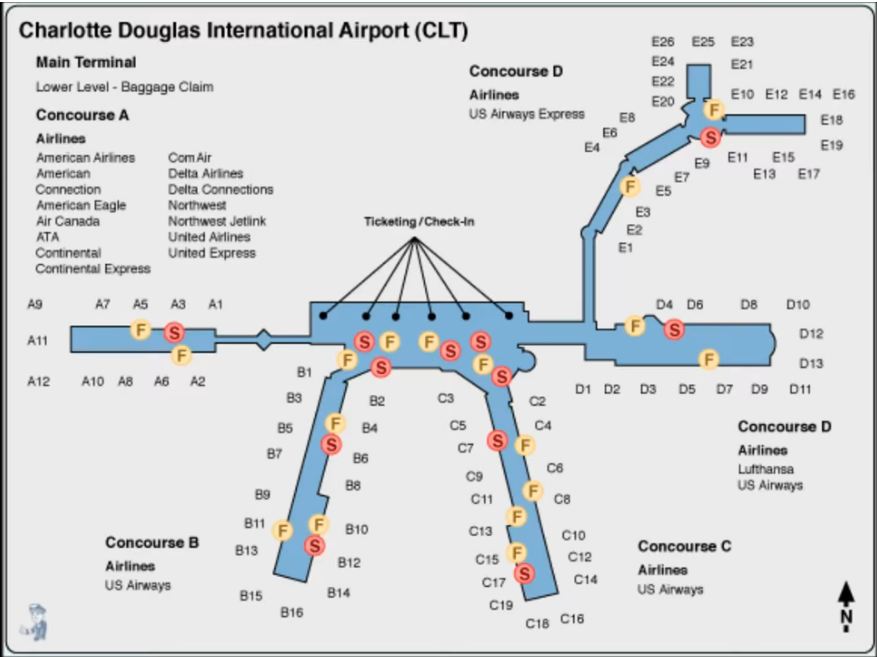

Though it’s hard to find a “there” there—or perhaps because of it—both CLT and the City of Charlotte put a lot of effort into distinguishing themselves from regional neighbors and fighting state legislators who think Charlotte is too rich, too powerful, and inauthentically North Carolinian. Charlotteans feel like their city is Jan to Atlanta’s Marsha or Tiffany to Atlanta’s Ivanka: the not quite as pretty or popular sister of the great New South capital just four hours to the southeast. CLT plays with the stats to appear closer to ATL in size and rank; the Charlotte Observer recently reported that while Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport is the busiest airport in the world, Charlotte-Douglas International Airport is the fifth busiest in the United States and the sixth busiest in the world…but only if your metric is takeoffs and landings; the same report also acknowledges that 80% of the passengers at CLT are making connections. The economy of Charlotte, like CLT’s, is centered on circulation, with the headquarters of Bank of America and NASCAR; it’s the 3rd-fastest growing city in the US, but only because more than half the population was born out of state.

(Like me: I’m from the other Queen City, Cincinnati, so the license plates I’ve had for my 1997 Toyota have said both “First in Flight” and “Birthplace of Aviation.”)

That the city doesn’t even sound like it borders South Carolina is one of many reasons state legislators in Raleigh—mainly Republicans from rural areas—love to hate on Charlotte, the state’s economic center. Tensions between Raleigh and Charlotte go way back, but they recently came to a head when Charlotte’s City Council passed legislation in 2014 adding LGBTQ people to the list of protected classes; in response, the state legislature passed the now-infamous “bathroom bill” known as HB2. As a result of the huge controversy around HB2, Charlotte now stands out from other biggish cities in one immediately visible way: it has way more gender-neutral bathrooms than bigger, more liberal cities like New York and London.

The airport has yet to follow local businesses’ lead; perhaps progressive bathroom signage would highlight the cis-normativity of TSA practices? But the city and the state have been fighting for control of the airport since long before the bathroom controversy. When the city began the process of (essentially) privatizing the airport’s administration, the state senate responded with legislation putting control of the independent authority in state hands, restricting the city to two seats on a 13-member airport authority board. Privatization wasn’t the issue—both sides agreed on that—but the largely-Republican state legislature perceived the move as a power-grab by the largely-Democratic Charlotte City Council, and responded with an even more audacious power grab. Today the airport is governed by the city, though city/state tensions remain; Charlotte state representative Jeff Jackson is one of the leading critics of Republican state legislators’ abuses of power, such as gerrymandering and their attempt to pass the 2018 state budget without letting it go up for public debate.

Raleigh might see Charlotte as full of carpetbagging liberals, but its deep Bible Belt roots are barely hidden behind the shiny shopping-mall veneer. Most major roads are named for the churches they lead to: Sharon Amity Road stretches between Sharon Presbyterian Church on the south side of town and Amity Presbyterian in East Charlotte. Billy Graham was born in Charlotte, his library and ministries are still headquartered there, and his funeral was a media event comparable in scale and audience enthusiasm to the British royal wedding. To get to the airport, you must take Billy Graham Parkway; no surprise that the bathroom attendants tell women at CLT to “have a blessed day.” The YMCA is the only other place I regularly hear the phrase, but the CLT bathroom attendants are contractors hailing from nineteen countries; perhaps the tips are better than if you say “have a safe flight.” But though CLT remains the only airport in the country with an attendant in every bathroom, tipping was eliminated in 2016; only the folksy appeal to church-going American manners remains, as these men and women from around the world hand you mints and mouthwash.

These traces of old southern religion reveal the veneer of neoliberal “progress” as New South cities like Charlotte double down on conservative values. While the 1971 Supreme Court ruling in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education forced this very school district to bus students across town, to integrate schools, Charlotte-Mecklenburg has become the most segregated district in the state. The beef between Charlotte and Raleigh is about style, not substance.

The shopping mall aesthetic of both CLT and the city of Charlotte is one such stylistic choice. In the late 20th century, malls came to be emblematic of the privatization of public gathering spaces. And though the mall is a dying social and economic institution, CLT uses mall aesthetics to hide the militarization of private space by the security state, masking this ongoing project behind a more familiar, almost retro version of neoliberalism. Like the city it’s named after, CLT projects an image of capitalist respectability—the placeless homogeneity that comes with financial success—over deeper quirks and tensions. I would quote a famous Ludacris lyric here, but he’s from Atlanta.

Robin James, airports, North Carolina, politics