February 4, 2018

Brooklyn, NY

First I did what everyone does every morning: stay in bed and fuck around online on my phone. I was so amused by the hilarity of a few tweets I’d fired off (sample: “ ‘Hand Solo’ is the porn version of Hans Solo where a guy who looks like Harrison Fords jerks off in space for 3 hours”) that I didn’t notice an hour or so had passed. I no longer had time for both a cup of coffee and a shower. I went to the kitchen, shoveled a spoonful of instant coffee crystals into my mouth, and chased them with tap water.

I did mean to get in the shower right after that, I really did. But somehow I ended up at my desk, fucking around online. Eventually a shower was out of the question as well. I got dressed quickly and plunged myself into a cloud of Kiehl’s Musk Eau de Toilette Spray. This is the whole of my morning’s grooming routine on more days than I care to admit. I have no idea whether or not my coworkers notice.

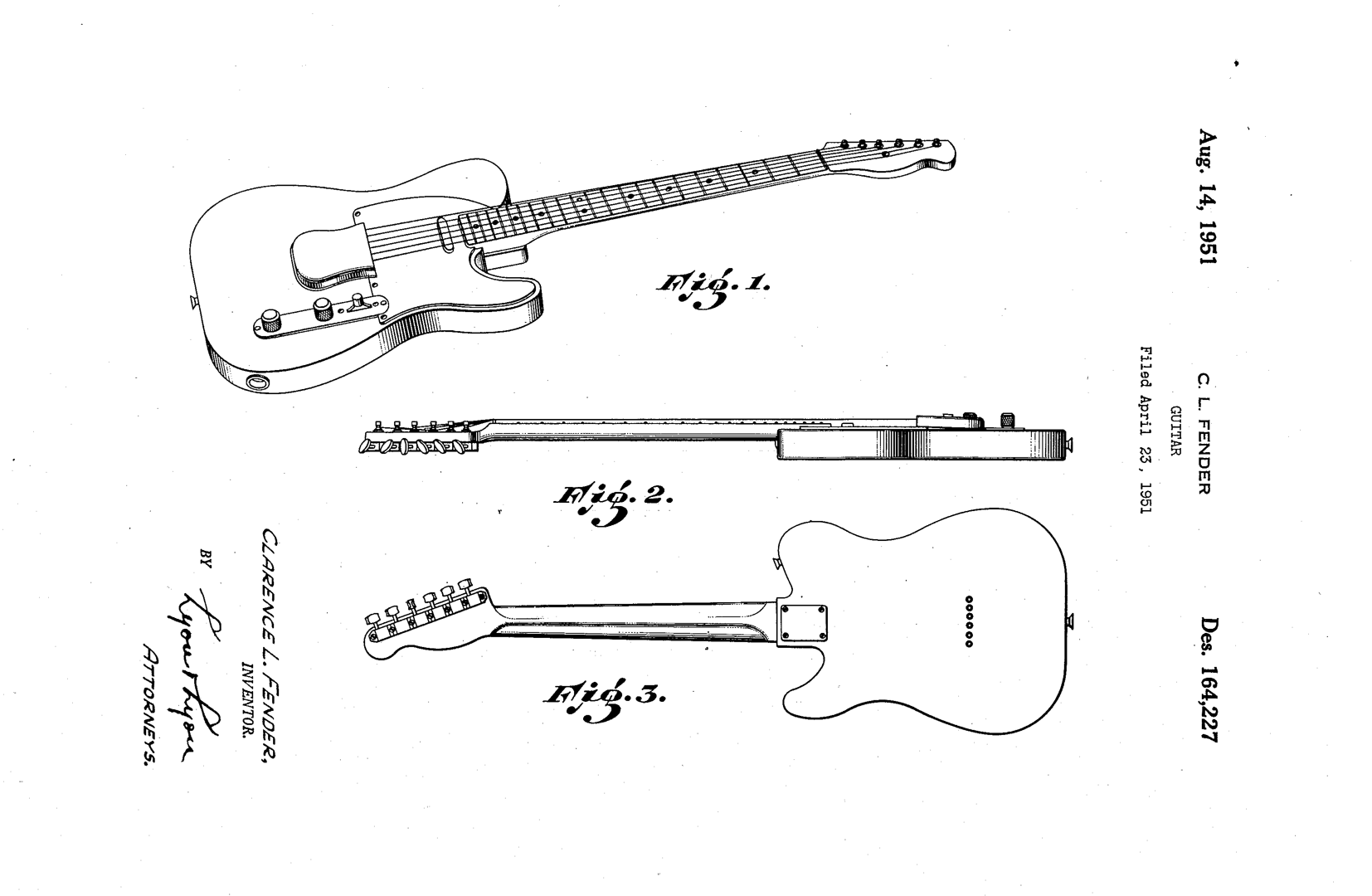

The most meaningful decision I make every morning is what music to listen to on my commute: a half hour or so riding the M Train from Bushwick, my neighborhood in Brooklyn, to the office where I work in Chelsea. This morning, I had an agenda. I’ve played guitar since I was 17—power pop and country, mostly, and I have, at various points, been in bands—and have only gotten more serious about it as I’ve gotten older. But this winter, I stopped playing. I’m not really sure how to explain it. Seasonal affective disorder? I don’t know. My usual reflex of reaching out for my Telecaster, positioned on a stand adjacent to my desk, had gradually tapered off to the point where I hadn’t even touched the thing for months.

So my agenda was to inspire myself to start playing again. The usual music I listen to—and play—hadn’t been doing the trick. It was time for something different. I decided to try what is sometimes called “shred” music, a style of music played on the guitar that pretty much no one listens to except guitar players.

“Shredding” is a description less of a musical style than a technique; the genre exists in the player’s fingers rather than the listener’s ears. It tends to sound like metal, but instrumental, often with pretensions towards classical structure and form. It’s epitomized by the Swedish guitarist Yngwie Malmsteen, whose appearance is characterized by the wardrobe of a swords-and-sorcery fantasy movie and facial expressions reminiscent of porn.

The guitarist on Ozzy Osbourne’s first couple records and the guy in the Scorpions are often cited as pre-shred shredders. Personally I’m not wild about solo Ozzy, and I am completely unfamiliar with the work of the Scorpions except “Rock You Like a Hurricane.” Most shredding music is bad. Some bands that influenced shredding—Van Halen chief among them—are often very good. But when unaccompanied by a singer or other instrumentation, shredding usually sucks. Just think of Van Halen without David Lee Roth.

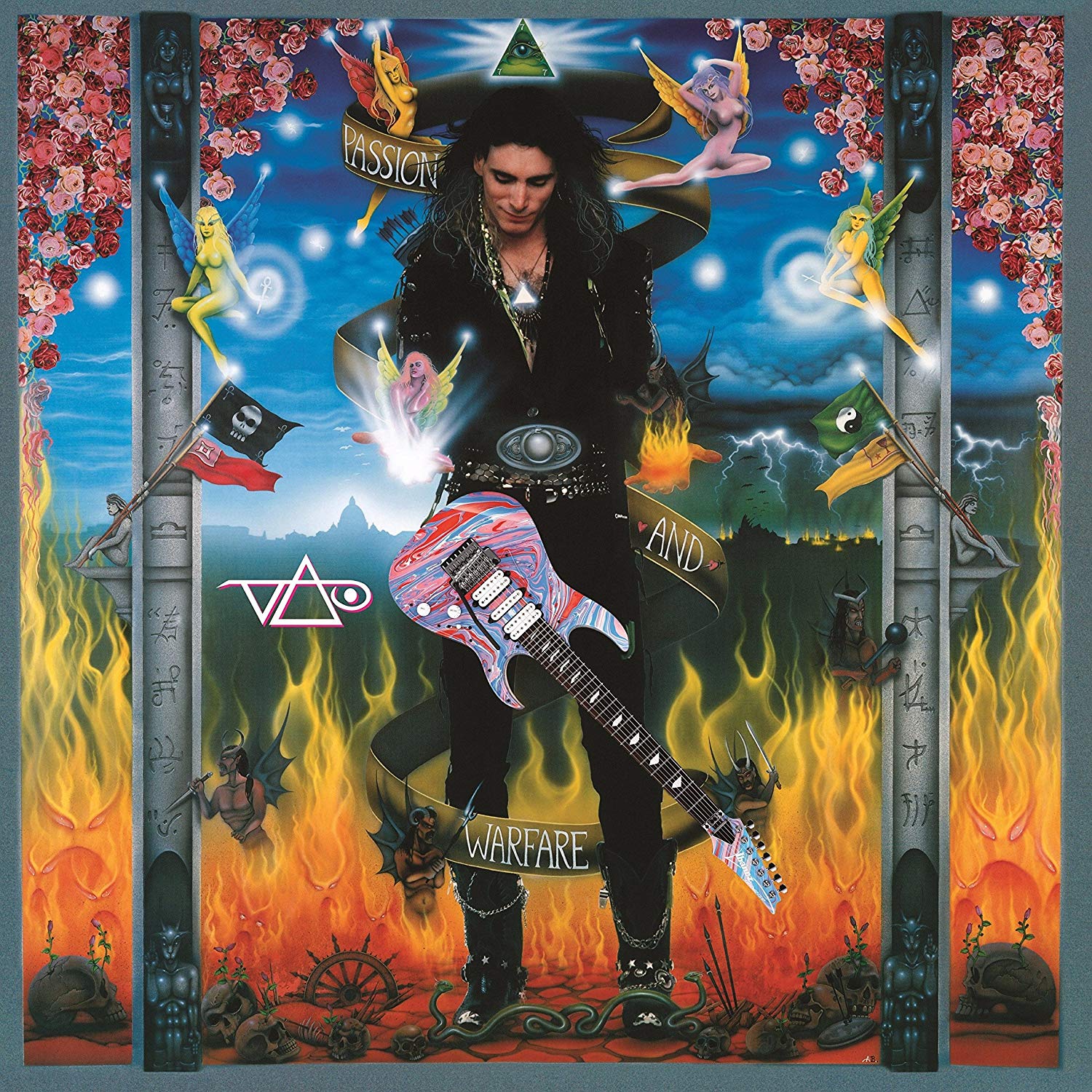

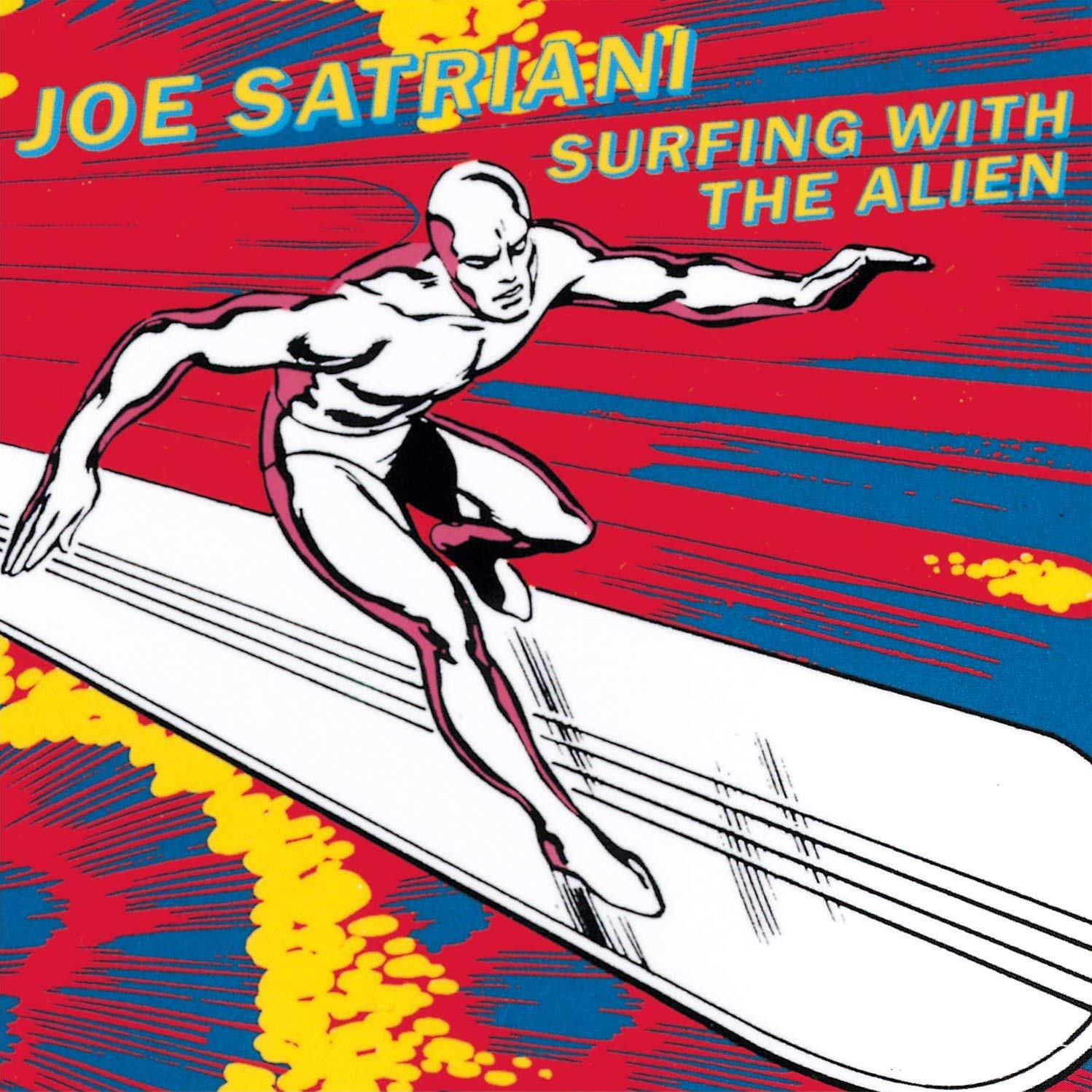

Guitar music exclusively for guitar players is probably prefigured by Jeff Beck’s mid-seventies albums Blow by Blow and Wired, which are legitimately good, and started in earnest a decade later by Joe Satriani and his student Steve Vai. On my way to work I listened to Vai’s 1990 album Passion and Warfare and was surprised by how good it was. The qualities completely lacking in the Yngwies of the world—self-awareness and a sense of humor—are there in abundance. After all, this was the guy whose first job was transcribing scores for Frank Zappa and who was the first guitar player David Lee Roth hired for his classic first record, Eat ’Em and Smile, after quitting Van Halen. I was already feeling an itch to play.

For years, my habit has been to watch TV with the subtitles on while practicing. This has the advantage of occupying my mind so thoroughly it doesn’t have the chance to do what it usually does, which is worry. But it does have some drawbacks. For one thing, it doesn’t work with comedies, because the subtitles ruin the jokes. More importantly, it’s a major constraint on making progress on the instrument. Without giving your playing full attention, you can’t accomplish much.

I remember reading a book on neuroscience once that said that the reason kids learn things faster and better than adults isn’t because their brains are more malleable. It’s because they’re more comfortable with things they can’t do. They’ll do something they can’t do repeatedly without getting discouraged or embarrassed, and eventually they’ll be able to do it. Adults aren’t good at this. We hate not being able to do things. So we just repeat things we can already do, instead of trying things we can’t do. Me, I sit there and watch episodes of various franchises of Law and Order and Star Trek that I’ve already seen, while I play stuff I already know how to play, and nothing changes.

I used to take guitar lessons from a legitimately great musician named Jim Campilongo. He plays in a style somewhere between Roy Nichols, the lead guitarist of Merle Haggard’s backup band The Strangers, and John McLaughlin, the guitarist on Miles Davis’s first few electric records. We trailed off when I stopped practicing. But as I listened to Vai, I remembered something Jim had told me. He’d emerged professionally later in life than most musicians do, assisted by the publication of Steve Vai’s practice routine in the magazine Guitar World. In 1990, the same year Passion and Warfare was released, Vai had shared his “10-Hour Guitar Workout” with Guitar World readers, including Jim. He’d begun collecting obscure country and jazz guitar records at the time as well, but it was the kind of discipline present in the Steve Vai Workout that helped him develop his own singular style.

On my lunch break from work, I walked over to the nearby Guitar Center on 14th Street and bought a book called Guitar World Presents Steve Vai’s Guitar Workout, which I believe makes me the male version of what people call a “basic bitch.” Since 1990, Vai has expanded the workout to 30 hours, which is more than there are in a day.

After that I went to the liquor store on the next block. It’s a modest, unpretentious liquor store run by a middle-aged Indian man who looks like he could be one of my uncles. To my surprise, I noticed he had three bottles of Old Rip Van Winkle Kentucky bourbon behind the counter. This is one of the most sought-after liquors in the world. There was a 10-year, a 12-year, and a 15-year, which cost $549.99, $699.99, and $1,199.99, respectively, for a total of $2,449.97. I asked him if I could take a picture of them, because I’d never seen a bottle of Old Rip Van Winkle in person before. I posted the photo to Twitter, with the caption “Just spent $2,350 on these babies,” because I suck at math. In reality, I spent about $80 on gin, Campari, and sweet vermouth, but people online seemed to genuinely believe I spent $2,350, which is more than I have in my bank account.

On my commute home I listened to Joe Satriani’s 1987 album Surfing with the Alien. It’s also good, maybe even better than Passion and Warfare, full of pastiches of different musical styles as filtered through the shred ethic. When I got home, I fixed myself a negroni and reached for my guitar. Usually when I start playing, I start with something like the last thing I listened to, but I don’t know how to play any shred music. It’s fast, and in spite of having played for many years, I can’t play that fast. So I made something up. I mapped out how to play every chord of the major scale across all six strings and tried to play them continuously, in succession. It’s the kind of thing I’ve always known how to do in theory but never bothered to sit down and actually do. I couldn’t do it. So I did it again.