It’s only fitting that the grass covering a tramp’s grave is littered with pocket change. Obols, the Greeks called them, the coins mourners would place on the eyelids of the dead (or slip into their mouths) so they could pay Charon the ferryman’s fare to cross the River Styx.

There’s other things people have left behind at Norton’s grave: bouquets of gladiolas and pink carnations; a battered gray beaver hat, just like the one His Majesty always wore when he made his daily rounds through San Francisco and a few Discordian Pope cards. In the chaos religion of Discordianism, Norton is considered a “Saint Second Class.” I have a wrinkled, faded Pope card folded up in my wallet; these are a lot nicer. Laminated, printed on crisp white paper, the cards declare:

The Bearer Of This Card

Is A Genuine And Authorized

POPE

So please Treat Him Right

GOOD FOREVER

There are also some notes pinned to the ground with rocks, poems and letters. A part of me is tempted to read them, but I think better of it. It would be unseemly for a lowly subject like myself to read a letter meant for an Emperor.

“On the reeking pavement, in the darkness of a moonless night, under the dripping rain . . . Norton I, by the grace of God, Emperor of the United States and Protector of Mexico, departed this life,” the San Francisco Morning Call wrote on January 9, 1880. Norton had died the day before, collapsing on the corner of California Street and Dupont, right in front of Old Saint Mary’s Cathedral. The city’s press corps raced to see who could give His Majesty the most florid obituary. The San Francisco Chronicle put his obituary on the front page, declaring “Le Roi Est Mort!” in bold letters. Norton, a pauper, was given a statesman’s funeral procession. Over 10,000 mourners visited his body before it was interred in the Masonic Cemetery, where he would reside until 1934, when the City of San Francisco moved all the remains in the Masonic Cemetery to the Woodlawn Cemetery in Colma.

Colma, the “City of the Silent,” is where the Bay Area keeps its dead: a necropolis of rolling green fields, verdant trees, and miles and miles of stone markers casting still shadows across the earth. It’s the subject of a lovely work of speculative/literary fiction, Alive in Necropolis by Doug Dorst, coincidentally the winner of the Emperor Norton Award bestowed annually by Tachyon Publications in San Francisco.

Colma houses over a million souls in its soil.

Marked by a sleek gray headstone with a slanted top, the Emperor’s grave is one of the town’s most popular destinations, enough so that I didn’t even have to drop his name when I swung by the Woodlawn office. All I had to do was say that I was trying to find a particular grave, and they slid a map to His Majesty’s plot across the counter.

Walking across the cemetery on a chilly afternoon, I surmised that the thing that drew so many pilgrims to Norton’s grave was the same thing that made him a hero of mine ever since I first found out about him in Neil Gaiman’s Sandman issue #31: he was an emissary from a better world.

Norton was a rich man in San Francisco before a bad investment in a Peruvian rice shipment torpedoed his finances. Bankrupt and in his forties, he began the second act of his life on September 17, 1859, when he barged into the offices of every newspaper in town to drop off a decree proclaiming himself “Emperor Of The United States,” the first of many he would issue over the years. Norton would issue orders demanding the disbanding of Congress, the construction of vast bridges over the Bay Area, the formation of a league of nations. He declared that anyone calling San Francisco “Frisco” would be fined $25.

The city’s journalists ate up Norton’s antics, turning Norton into a living tourist attraction. One of his biggest boosters was Samuel Clemens, aka Mark Twain, who based the King in Huckleberry Finn on Norton. On his daily rounds, wearing a blue uniform with gold epaulettes and a beaver-skin hat with a peacock feather, Norton would collect “taxes” from his subjects.

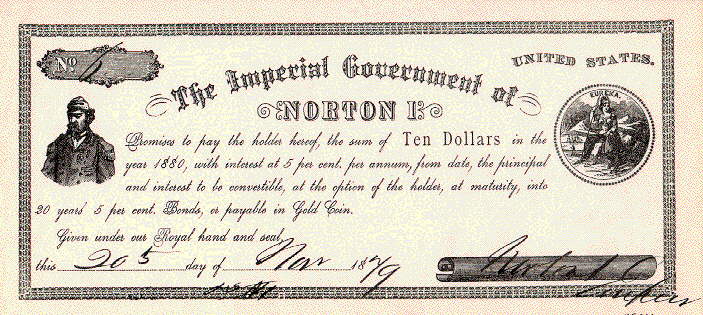

When his uniform started to fall apart, the city’s Board of Supervisors bought him a new one. Policemen would salute him as he made his rounds. When an overzealous officer arrested Norton and committed him, the public outcry was so severe that Norton was immediately discharged. In a gesture of supreme magnanimity, he gave the arresting officer an imperial pardon. Norton even created his own currency, Norton bucks, that was accepted as legal tender. Long before blockchains and Bitcoins, Emperor Norton was conjuring money out of thin air.

San Francisco could have run the Emperor out of town, imprisoned him, committed him, ridiculed him. Instead, they chose to play along. Rather than tell the Emperor he had no clothes, they complimented him on his shiny epaulettes and pressed a few coins into his palms. He even got the census bureau to humor him. The 1870 US census lists Norton’s occupation as “Emporer [sic].”

Standing at Norton’s grave, I thought of all the eccentrics back home in Phoenix. The man named Chicago, who rides the light-rail in a suit of armor made out of soda can pop-tops. Elderly Space-Alien Donald, the “world’s oldest gay Canadian rapper,” who used to show up at house parties and rap about getting blowjobs from robots. The quiet man who stands on a milk crate on the corner of Fifth Street and McKinley almost every night, playing jazz guitar through a tiny amp. William Wonderful, the poet who sells xeroxes of his pieces outside record stores and coffee shops.

Whenever I was in their company, I always felt a breeze coming from their direction. Like there was an invisible rift behind them that they had slipped through, a slit in the air that could lead to a better world if you just pushed through it. A world where this kind of marvelous shit happens all the time—where everybody rides the train in soda can armor and monarchs are delightful, harmless bums and not psychotic real estate moguls with Cheeto spray tans.

The wind picked up in Colma, tipping the gray hat over on its side. I reached out over Norton’s grave, trying to feel an opening in the air. I left behind two obols and a folded piece of typewritten paper on Norton’s grave. I won’t tell you what I wrote: that’s for His Majesty’s eyes only.