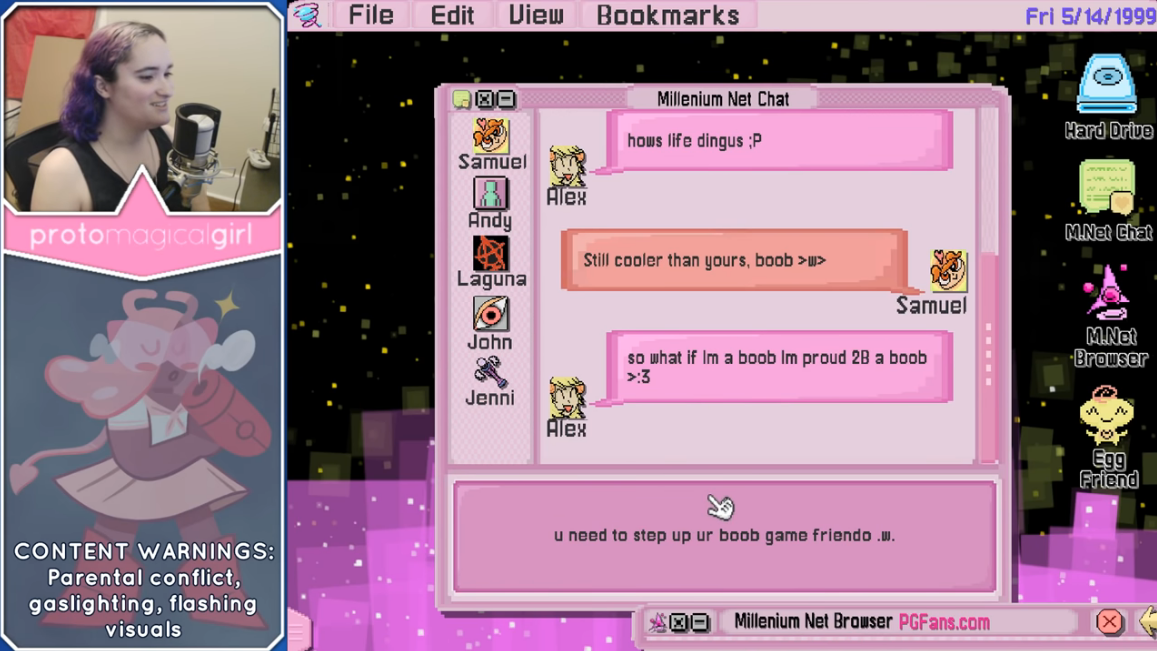

Start up Secret Little Haven and you’ll be starting up your computer, a sticky-sweet facsimile of the Unix box that you might have logged into if you were coming of age sometime in the late nineties. Alex—the character you’re playing—has spent no small amount of time or love in turning the computer environment into a teenage girl’s bedroom, bubblegum pink taskbars and all, but they don’t seem to realize it yet. Alex’s desires are found on the Internet, and on the Internet they take the form of early fandom, specifically around a Sailor Moon-esque magical girl anime. An online friend gives you the latest from the rumor mill: In the feature film that’s coming soon, Minori will *finally* be initiated to the Love Force, and will be able to transform with feminine elemental power like they do, but Minori is a boy.

In the way of a teenager on AIM chat, you blurt out an unconscious sort of thought: wouldn’t it be great to transform like Minori does?

“I certainly get what you mean,” their friend replies.

Alex, for the uninitiated, is an “egg”—someone who is trans, but doesn’t realize it yet. Like all of the fun words, it can be impolite if not used precisely: one can refer to themselves or someone else as an egg in retrospect, but applying the term to someone on suspicion of lurking girlhood has a way of selling the complexity of someone’s experience hurtfully short. If you want to play things safe (and if you aren’t very experienced in these sorts of narratives, you definitely should), you should stick with the words we include in the packet—”pre” and “post-transition”, “gender variance”, swapping “queer” with “LGBT” and dividing “gender expression” and “gender identity” like church and state. They’re the neutral words, terms we’ve designed so that you can get out of most conversations without ascribing narrative where it might be filled in by someone else. They’re the terms that we need, but they’re not necessarily the ones we crave.

The temptation behind using terms like “egg” is, simply, that they tell a better story. The folk etymology claims that it’s wordplay—start out as an “egg”, hatch as a “chick”—but it’s kind of its own thing at this point. Start out as something blank, formless, unrealized; coalesce and emerge as something utterly transformed, complex, and beautiful. Gender, surprisingly enough, takes a back seat in this story, transition within its language merely incidental to the discovery and pursuit of a certain kind of grace. A young person hunched over their computer, enamored with stories about spinning within light and transforming into something as powerful as it is feminine, might not grow up to be a girl (or something within the ballpark). But the desire to read several steps ahead in that story, past reality, is perhaps because we want the girlhood that we dreamed of back then, instead of the one we got.

Out of all the things that gender can be accused of, perhaps the most immediately felt for trans girls like myself is that it’s fucking boring. The dream, back then, was girlhood as synecdoche for the intimacy of slumber parties and the blissful mysteries of casual touch, for a body that flowed as much as it was a coiled spring. We got that, certainly—there wouldn’t be much point to the whole enterprise if we couldn’t—but we got it in between pain (well advertised) and banal disappointment (not so much). For every family, friend, job, or notion of safety, lost or gained, there’s an instance of mismatched expectations with realities, the girlhood we dreamed of not being quite the girlhood that we get to live. Our bodies don’t prove to be infinitely malleable, and neither do our circumstances, a universal pain that’s felt acutely here: a gap opens up between the ways that we see ourselves, and the ways that we want to see ourselves. We have all the words we need to describe the former; describing the latter is a more difficult task, requiring the language of our basic desires, the language of what we were drawn to as we were growing up. And that language can be beautifully, blissfully weird, something that pieces together bits of cultural minutiae and experience into something utterly singular; the beautiful absurdity of understanding yourself through, say, magical girl anime.

There’s a micro-generation of trans girls who were born in a particular moment of the development of the Internet in the West; a golden period where computers were generally accessible to affluent-enough families (you can line up the rest of the probable demographics here), while also being novel and misunderstood enough that the resident patriarchs of those families would be content to leave the “computing” to their children. In brief moments of privacy, we sat in the big, black leather chairs of our fathers, logged into their computers, and explored social and cultural spaces that overwhelmed anything we could find back on Earth, spaces where we could get our hands on anything that would let us search the ideas and desires that we couldn’t name ourselves. Secret Little Haven explores one particular path, but within that strange, hyper-connected, pseudonymous space, there was no shortage of others. The obvious throughline between these fandoms and past times is the malleability of identity, or, at the very least, the idea that one that you’re given isn’t necessarily the one that has to be true. But the point where they fracture, I think, is the specific appeal that these stories and activities hold to the potential egg.

In one of the game’s smartest moments, you’re asked to take Alex’s Pretty Guardian Love Force fanfiction from 1300 to 1500 words. There’s no predestined path for this—you’re actually sitting in front of a word processor—and it’s not a gag. Throughout the game, you’re asked to roleplay as Alex, with as much distance being removed from the audience and their embodiment of the character as possible (another puzzle requires you to print something out to your desktop, and the solution is that what you need was printed out to your “real” computer’s desktop). The audience, in this case, is the actor, but this moment is just about as close as any other work in the medium has come to allowing you the full fidelity of expression and creative freedom that comes with acting. Writing fanfiction is an exquisitely private activity, specifically attuned to private wish fulfillment, and here you’re asked to write the next chapter to someone else’s private fantasies.

If you’re worried about not living up to the task, then rest assured that the bar to impress is very low: the game can’t tell the difference between you taking the project earnestly, and you writing out the word “FEELINGS” 200 times. Chapter One of “Finding The Warmth”, titled “Izumi Could Only Lay”, employs its titular phrase about thirty different times, in case you didn’t realize that there was in fact A Motif Going On. In this telling, Izumi is deeply insecure about her place in the Love Force, having slightly botched the execution of last week’s Fight Of The Week. She’s terrified that Hotaru thinks less of her–and, this being fanfiction, things are resolved by Hotaru informing Izumi that she actually thinks the world of her, and shares the same anxiety in reverse. (To be fair, a teenager—you—did write this.)

What happens next is, quite literally, your call. For myself, I went with the infamously tried-and-true: picking up on the cues of budding admiration, I decided that Izumi and Hotaru would find themselves checking into an inn after a long night of travel, but only one bed is left, and it’s just so gosh dang cold, and it’s not like I think you’re cute or anything but I just want you to know that you’re so powerful, you know, y-y-you t-t-too, tune in next week for Chapter 4: Izumi Thinks About This Five Years Later In College And Goes “Oh”. The frame given in the game isn’t explicitly trans—the characters in the fanfic are cis, unless you really don’t want them to be—but you’re handed the beginnings of a story where the love and vulnerability of others can help you understand yourself not as a burden, but as a conduit for a grace of your own design; my story crossed those wires with intimacy as a pathway for becoming comfortable with that power. It wasn’t trans in any textual sense, but it didn’t need to be.

I transitioned several years ago, while I was at college, but I had to go back into stealth mode when I returned home for my grandfather’s funeral. As they were ratcheting the honorable judge into the ground, I thought of a moment from the children’s show Steven Universe that I’d watched alone in my hotel room the night before. In the show, Steven spends the whole episode preparing a friend for a bubblegum-pop diva performance at the town talent show, only for her to shove the dress, make-up, and mic back in his face. She never wanted this, but he realizes that he always did, and he goes on stage and he fucking nails it. The story isn’t trans in any explicitly textual sense, but it doesn’t need to be. He wanted something tremendous, and he didn’t deny it to himself on account of its being saccharine or feminine – why he wanted it wasn’t even a question. He might not be an egg, but he chose his grace and he took it.

Perhaps the word doesn’t live up to the task, but I think that’s trans as hell.