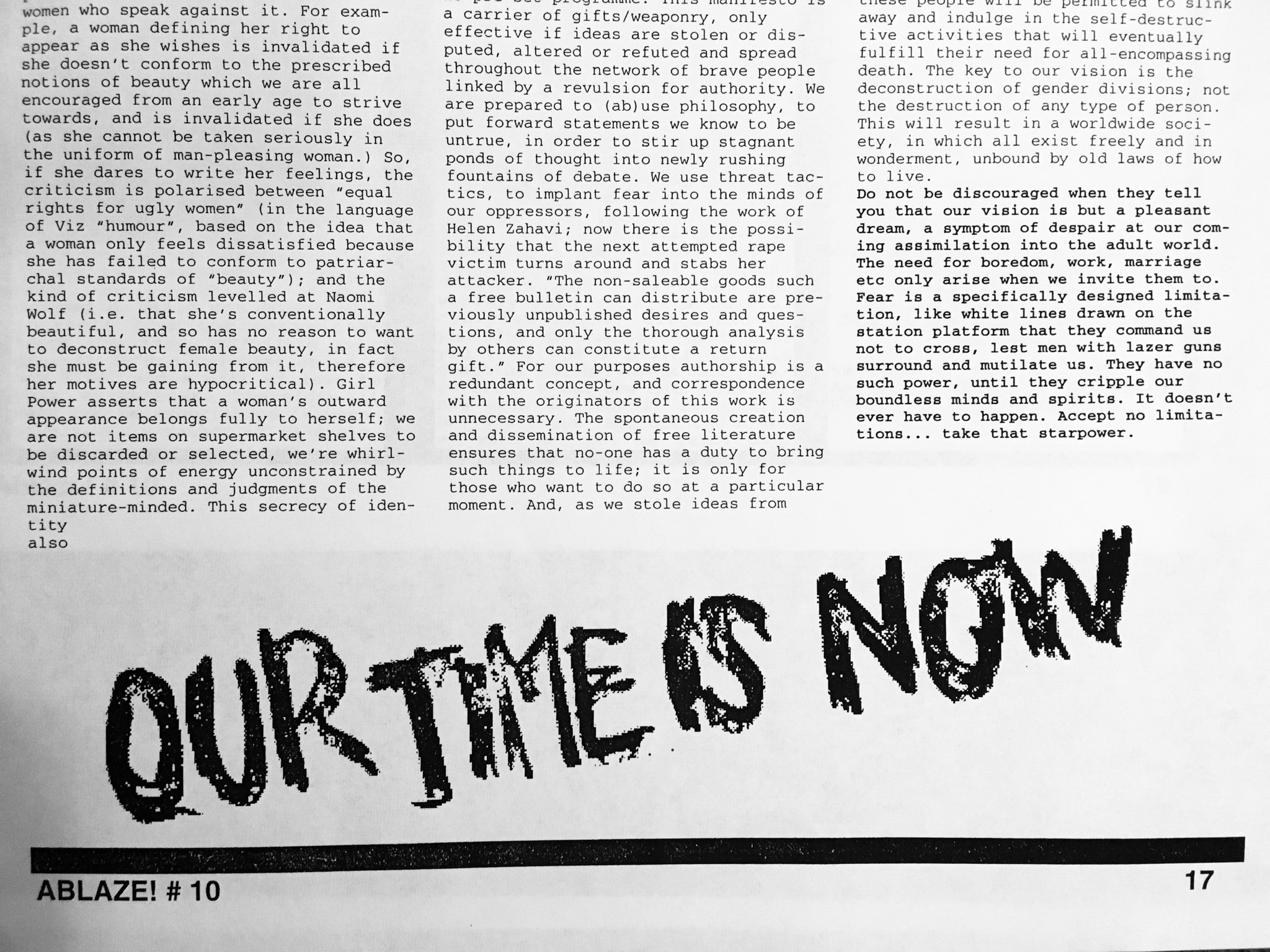

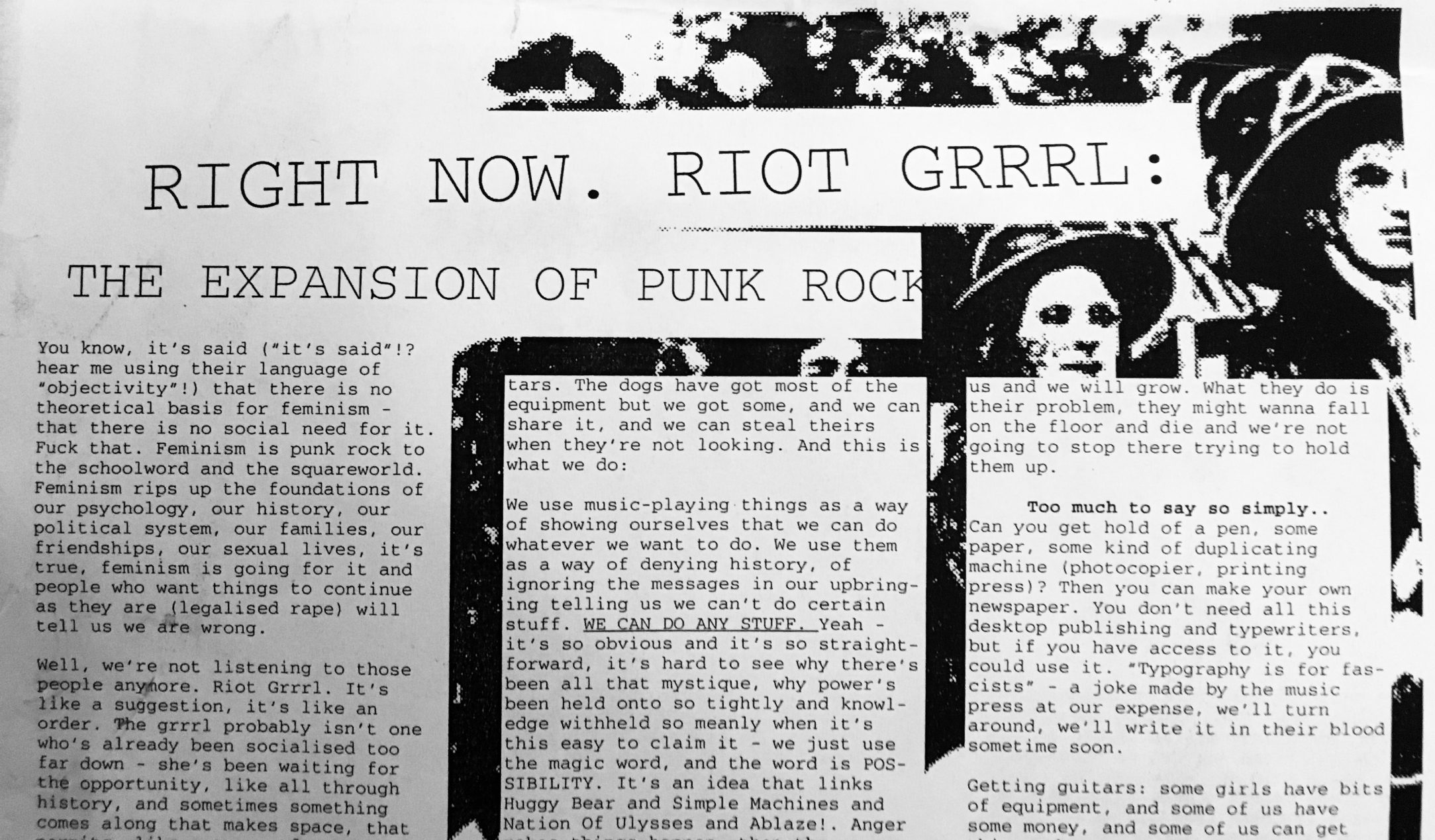

“Some girls have bits of equipment, and some of us have some money, and some of us can get things cheap—we’ll figure out ways.” These typewritten words were seared on a xeroxed page in May 1992 after the words “Getting Guitars,” in a manifesto in Ablaze!, a British fanzine. Writing in defiance of the centralized and patriarchal creative deadzones, “the schoolworld and the straightworld,” the anonymous authors described the Man’s obsession with objectivity by the figure of “little pug-dog type monsters,” all those who hoard resources from would-be revolutionaries, the “slow, perfectionist” squares, who are always “fouling things up with their petty competitive ways.” In a burst of chaotic optimism, the authors drown them out: “We can’t hear them just now, over the beautiful weird electric scream of our newly switched on guitars.”

In this moment, underground music colluded with writing against the powers that be. This text is one of hundreds of such manifestos exchanged in the early 1990s; reading through the zines, press releases, and correspondence from this time, one gets a sense of the depth of music’s role in contemporary political debates as the idiom of struggle and destruction. Somewhere within these D.I.Y. networks, some of these young feminists began describing themselves as “riot grrrls,” organizing to help each other form bands, throw shows, and make recordings together. It’s impossible to count the bands that emerged under this banner.

That was the riot grrrl then; in the time since, the riot grrrl brand has become a retrospective antagonist to whatever we need it to oppose: feminism to the marxists, punk to the feminists, commercialism to the punks. In his book 1989, Joshua Clover presents riot grrrl as a dramatic foil for grunge; in “Signifying Nothing,” Jeremy Gilbert positions riot grrrl (alongside Public Enemy) as archetypically “political” music, so visceral it must be analyzed for its affect, not merely its meaning; and critics who don’t bat an eye at Kurt Cobain’s vast, platinum whiteness still tear Kathleen Hanna to shreds for hers, using riot grrrl as code for the whitest of privileges—rich girls who’ve only just woken up. In each of these instances of cultural memory, “riot grrrl” gets memorialized as a coherent movement, one fixed enough to warrant reference, archives, and anthologies.

It’s in the sense of its coherence—as a banner became a brand—that riot grrrl acquired its very own Wikipedia entry, first published, in rough form, in 2003.

The feminist texts and sentiments of the nineties are not easily summed up: in real time, these songs and zines and manifestos circulated in constant tension with each other and everything else, their “feminist” features fading in and out of focus alongside other concerns. Indeed, formal riot grrrl archives, like those at New York University or the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, contain thousands of artifacts from the era, but not only specifically “riot grrrl” materials. The world of early-nineties feminist music overlapped with a myriad of other contemporary causes, and so they house the variety of subcultural artifacts from all over the world that the girls exchanged and kept in their collections; alongside manifestos, one finds writing on the AIDS crisis, fights for abortion access (again), and what one zine called “multi-subculturalisms,” the ongoing dilution of radical race politics with corporate affirmative action quota-ism.

In pinning down the riot grrrls’ place in these overlapping currents, Wikipedia begins by posing two possible birth cities, Olympia and Washington, D.C. But most of the nineties grrrls couldn’t have cared less about this kind of narrative; they relished presence and rejected posterity, and resented lines of influence (or at least wanted to look like they did). The Ablaze! credits, for example, announce sincerity and proselytize Real, Actual Action: “We’ve got a lot of work to do—not to become media stars, but to fulfill our intentions.” Spreading the good D.I.Y. word that “every girl is a riot grrrl,” women in these circles urged their friends to craft their own guidelines from scratch; as Molly Neuman, drummer of the band Bratmobile, wrote, “There is no editor and there is no concrete vision. This name is not copywritten [sic]… so take the ball and run with it!”

Despite how riot grrrls fetishized action over representation, histories of the movement almost inevitably turn towards the problem of profit, and the “riot grrrls” always seem to become a story of lost authenticity and anxiety about selling out. As Wikipedia tells it, this decline begins in the mid-nineties:

This all feels mostly right. I’ve never seen any riot grrrls take down the Spice Girls or Lilith Fair in particular, but it’s the kind of story that reads well enough to make you ignore that [citation needed] there at the end. And it is true that the name riot grrrl—coined in 1991, in the aftermath of the Mount Pleasant riots, according to some accounts—was “co-opted” basically immediately. As early as 1992, magazines like Glamour and Cosmopolitan were already covering the movement and using its transgressive language of self-determination to sell their magazines. This irritated some; in a 1993 issue of Riot Grrrl NYC, the editor’s note quotes a headline from seventeen—“Will Riot Grrrl refocus feminism or fry in its own fury?”—and retorts: “So we’ve got them curious. So what?” But the story has been repeated ever since, often with the Spice Girls as the villain: in a 2017 piece on nineties nostalgia for i-D, Erica Euse writes that “[riot grrrls’] reclaiming of girlish hairstyles like pigtails was co-opted by groups like the Spice Girls and mall retailers like Limited Too marketed ‘girl power,’ but without the radical politics.” A 2018 review of 90s Bitch, a new book by Allison Yarrow, reads similarly: “Most women probably know Riot Grrrl from its derivative forms: the mantra of ‘girl power’ espoused by the Spice Girls.”

This riot grrrl take is frozen in time, locked in combat with the Spice Girls. And yet there’s something too tidy about the way this movement’s splintering and co-optation happens so immediately after its birth, almost defined by its perfect antagonist. Where does the dynamic come from? Have these writers read the Wikipedia entry, and if so, what did they think? Is their work shaping the Wikipedia knowledge store, or being shaped by it?

These fables about diluted authenticity have persisted, in part, because the Wikipedia entry does what encyclopedia entries do: it tracks a linear history, emphasizing equal parts change and continuity by painting a graceful arc from the early nineties through today. Like everything that riot grrrls sought to overthrow, encyclopedias take clarity for truth, order for beauty, and coherence for knowledge. Such “objectivity,” however, can capture none of the verve present in the girls’ actual creations, none of their subtle wordplay and affectionate humor, their cryptic slang and remarkable concision. Some voices were measured, meditative, self-conscious: “I have the privilege of ignoring my privilege,” one girl writes solemnly, to an unknown audience. Others were genuinely unconcerned with how they came off, playing freely with form and language. “Right now it doesn’t make sence [sic] but neither do we!” wrote two girls of their emerging project together.

The brevity and predictability of the entry’s “Criticism” section is striking, suggesting only two very conventional categories of judgment: claims of racialized bias, and general ignorance about trans experiences. But given the richness and importance of these topics, the concerns evinced by the entry and its edit history are surprisingly tame. There is some conceptual banter (e.g., about whether animal rights is a gendered issue), and edifying questions about history are raised: “Luscious Jackson an important influence?” For the most part, however, the list of edits to the entry reads like a teacher’s feedback: “weeded redundancies,” one editor logged in 2016. These gentle writerly quibbles have nothing on the forthright ideological insults flung among young feminists of the nineties. In bouts of performative rage, they freely dragged rivals, both indirectly in their art and directly in their letters, producing a climate of conflict not unlike social media today.

If Wikipedia describes riot grrrl as “a movement in which women could express themselves in the same way men had been doing,” the protagonist in Sarah Schulman’s 1992 novel Empathy reflects the milieu’s ambiguities when she reflects that “I fear being told that I really want to be a man. It’s an accusation that everyone seems to make.” Whether women want to be men, let alone can be, is a longstanding landmine, loaded beyond measure. And so, in the archives, we find heated takes accruing and intersecting about whether to be a woman, or just detonate the category itself; on one page, a dyke accuses a straight woman of “bigtime privilege”; on the next, Gunk editor Ramdasha Bikceem calls out a white girl refusing to confront her biases: “Ever heard of the word Guilt???” Meanwhile, boy zines wax persecuted, and the girls retaliate with analog, snail mail subtweets: “Chris has a lot of supposedly open-minded PC opinions […] but I’m thinking he’s trying to cover his ass instead of really trying to envision other people’s social/political struggles.” Confessions of infidelity! Literal death threats! Self-loathing writ small in tiny cartoons and meticulous collages, stitched together with a needle and thread. And all the while, comrades half a world away from each other went on exchanging handmade tips for self-defense in the face of the world’s abuses, using music as both catalyst and antidote, the soundtrack to every outer and inner war.

***

The concept of a wiki dates back to 1994, the same year riot grrrl was described by the L.A. Times as an “international postal salon.” And like the riot grrrls, Wikipedia aimed to democratize knowledge and rethink how it moves. Anyone could start a band—and should—and anyone could edit a Wikipedia entry. But amid the blossoming of chatrooms, bulletin boards, and wikis, there was a polarization in the world of D.I.Y. networks, between cyberphobia and techno-optimism. Riot grrrls tended toward the former, quoting the 1995 anthology Resisting the Virtual Life in their zines, or preciously admitting that “computers scare me with their exactness and precision.” By contrast, Wikipedia redeemed the world wide web. And while Wikipedia entries sometimes read like punk zines—especially on lower-profile subjects, they are often captivating repositories of the errant, misguided, and commonplace—Wikipedia entries seem strikingly dissatisfied with their amateur status, aspiring to what people think Knowledge should be. “Added sentence to provide a more definitive explanation,” explains one edit on the riot grrrl entry.

The riot grrrls were content with absence of “definitive” expertise on their topics. On the back of one copy of Johanna Fateman’s zine It Grosses Her Out, someone annotated: “Our only hope is in thrill-seeking, the desecration of masterpieces, and the rejection of family values.” If this insight is right, and liberation lies in destruction, can the movement even be said to have had a “moment”? A stable mainstream? A coherent rise and fall?

Should there … be an entry on it at all? Perhaps the D.I.Y. ethos of the riot grrrls doesn’t thrive in archival (or encyclopedic) captivity. Riot grrrl has often been derided as awash in white privilege—and who would deny that it was?—but as Gabby Bess observed, in her 2015 article, “Alternatives to Alternatives,” riot grrl’s whiteness has also been a product of its canonization: when eager stock accounts emphasize the movement’s white mainstream, attempts to acknowledge what Alice Echols called “snow-blindness” among white feminists can actually help to produce it, “glossing over the contributions of black women and other women of color.” Even to describe the scene as “a subcultural movement” might impose a misleading coherence; as early as 1994, scholars Joanne Gottlieb and Gayle Wald characterized the by-then popular movement as a “bona fide subculture,” but Kate Eichhorn, for example, regards riot grrrl as avant-garde, implying a more rarefied aesthetic (and cultural force) than the marginality associated with movements subordinated by the prefix sub-. We can imagine, if dimly, how the entry might read if its premise were that feminist art of this time had more in common with the work of Zora Neale Hurston or Gertrude Stein than Clueless.

If some will argue that all third-wave feminist art was born commodified, riot grrrls were born to denounce such haters: in an infamous 1993 manifesto, distributed as liner notes to a Kill Rock Stars compilation, drummer Tobi Vail slams the cynical solipsism of those who are “busy trying to convince themselves that simply because they are no longer punk rockers, punk rock must no longer exist.” The music was esoteric, challenging, and often expert, and the writing often exceeded it. Johanna Fateman’s zine Artaud Mania remains a bracing critique of institutionalized knowledge—an elaboration of her call elsewhere for “a paradigmatic shift in the notion of genius.”

To write off the era’s brilliance in the service of some stale, insipid narrative about corporate co-optation only reproduces the dogs’ own bleak caricatures of commodification; it requires a cynicism caustic to the point of sabotage. Will the next round of edits infuse this topic with the kinetic zeal that made history budge in a way that felt bounding to the riot grrrls? Maybe. When I hear about Wikipedia editing parties, where people gather to collectively transform what is known, I think of the 1996 zine cupsize. In it, an anonymous author reflects on the impact of the emerging computer age. “I think of a word and my fingers reflexively move a little on this misty keyboard in my mind; it is both muscle and mental,” they write. Keyboard, here, in both senses of the term. “Those that accuse us of slack have overlooked the power that lies in our fingertips.”