When the Great Depression left over 9,000 banks in ruins, the U.S. passed the Banking Act of 1933, which limited the amount banks could pay out in interest on personal accounts. The theory behind Regulation Q, as this measure came to be called, was that banks competing for badly needed funds during the crisis years had bid interest rates up to catastrophic levels. Reg Q was intended to help the remaining banks survive: the less you have to pay out to savers in interest, the healthier the profits.

Twenty-five years or so down the road, this innocuous-sounding law would play a significant role in the world financial markets, and one its framers could not have predicted, paving the way for the explosion of the Eurodollar and Eurobond markets, and the corresponding collapse of New York’s dominant position as the world’s financial capital.

The story is of particular interest a time when Washington is again playing fast and loose with trade and economic policy in Iran and elsewhere. Ours is not the first era in which the government has flexed its muscle in an attempt to “fix” economic and geopolitical problems. Among many previous attempts were two whose effect was to substantially undermine U.S. control of global finance. So good luck with it this time, DC.

To answer our first question: A Eurodollar is a U.S. dollar held in a bank outside the U.S.—and, therefore, a dollar outside the direct control and regulation of the Federal Reserve.

The Marshall Plan for rebuilding Western Europe after World War II is often portrayed as an act of humanitarian generosity by a rich young country towards its frail and elderly grandparents across the water. And it was. But the Marshall Plan wasn’t entirely altruistic; it was driven to a great extent by Truman’s doctrine of “containment”— the desire to keep Stalin and communism out of Western Europe—which was generally endorsed by his conservative Congress. It may appear quaint now, but a communist takeover seemed like a real danger in European countries devastated by the war against Fascism—a conflict that had arguably sprung from the spectacular failures of past generations of a broadly capitalist persuasion. To many it seemed like time to try something new.

In 1946-7 in France, for example, the Communists were the largest political party; the French coalition government formed in May 1947 included five Communist ministers in its cabinet. Italy was barely less red, and Britain had booted out the imperially-inclined Churchill and elected an avowedly socialist Labour party with a long mistrust of capitalist bosses and their politician lackeys.

One result of the $13 billion Marshall Plan was that a lot of dollars were credited to bank accounts across the Atlantic. There were exchange controls at the time: currencies were generally inter-convertible for the purposes of trade (“current account”) but not for capital flows (investments); but still, dollars built up in the international banking system. Some of them ended up in the pockets of the dreaded communists, including China and the Soviet Union. Exact details of how the postwar financial markets in Europe developed are hazy, but many of the accounts begin with the communist countries and their wariness towards the United States in the early years of the Cold War.

One such story begins with Yugoslavia. Prior to the war, seeing the swastika on the wall, Yugoslavia sent a heap of gold to the U.S.A, where they reckoned it would be safer from the paws of grasping fascists. By 1948, formerly monarchist Yugoslavia was an independent communist state under Josip Broz, more commonly known as Marshal Tito. Tito sent to New York for his country’s gold, which amounted to somewhere in the neighborhood of $50 – $70 million, a tidy sum in those days. There was a fly in the ointment, however, in the form of American citizens of Yugoslav origin who had claims against the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (for example, for property which the government had nabbed from them). And so the U.S. decided to keep the Yugoslavian gold until these claims could be settled, as they were, after a couple of years’ delay.

The episode, or so the story goes, provoked qualms in China and the Soviet Union, who thenceforth deposited what dollars they had, not with banks in New York, but instead with two Russian banks of long standing in Europe, Banque Commerciale pour L’Europe du Nord (BCEN), founded by White Russians in Paris in 1921, and the Moscow Narodny Bank (MNB), whose London subsidiary was founded in 1919. (Both are now owned by VTB, a Russian bank with close ties to the state).

Other sources point to the 1949 revolution in China or to the outbreak of the Korean War, when China allegedly took the precaution of banking $5mm with BCEN through the Hungarian National Bank. Still others date the first of these deposits later, to the Hungarian uprising in 1956. We will likely never know the exact truth, because most of the original actors in these stories are dead and historians have come up with precious little in the way of supporting documents. However, there is agreement about the general tenor of events, namely that the communist countries thought their dollars would be safer in a European than an American bank: a plausible narrative, given the level of McCarthyite zeal prevailing in the U.S. during the first decade of the cold war.

The telex address of BCEN was ‘Eurbank’, and dollars deposited in banks outside the U.S. thus came to be known as Eurodollars. The great benefit to the depositors was that, because these banks were outside its jurisdiction, the U.S. could not identify the owners of the dollars. All they would see was that BCEN or MNB had credits for dollars at money-center correspondent banks in the U.S., and what the U.S. couldn’t see they couldn’t freeze, no matter how hot their Cold War ire.

The question these Russian banks faced was, what do we do with all these dollars? (For the explanation which follows, the author is indebted to Dr. Catherine R. Schenk and her paper, The Origins of the Eurodollar Market in London: 1955-1963).

The Bank of England in early 1955 was worried about inflation. To counter this, it raised interest rates, so much so that the yield on Treasury bills (known in the UK as “gilts”) rose to more than 4%, a postwar high. The net result was that many depositors took their money out of the bank, where they were getting a little over 2%, and put it into gilts. The cost for banks to replace these deposits with borrowings from the Bank of England (“Bank Rate”) was raised to 4 ½%. With declining low-cost deposits, profitability was quite squeezed.

The Midland Bank, however, found a clever workaround. It could borrow U.S. dollars for 30 days at 1 ⅞% per annum (from, for example, the Moscow Narodny Bank). It could exchange these into pounds sterling and at the same time lock in an exchange rate to change them back again in 30 days, a transaction that cost it effectively another 2 ⅛% p.a. (this was made possible because of the lifting of restrictions on currency futures in 1954). The total cost then would be 4%, as compared to the 4 ½% Bank Rate. It doesn’t seem like much, but for a bank, 50 “basis points” on largish sums can easily mean the difference between profit and loss.

So why could they borrow the U.S. dollar so cheaply? At least partly because of Regulation Q , which dictated that banks in the U.S. could pay no more than 1% on 30-day savings accounts (or 2 ½% on 90-day accounts). The 1 ⅞% offered in London looked cheap compared to yields in sterling, but it was a fairly hefty premium compared to the dollar rate prevailing in New York, and proved attractive to the likes of BCEN and MNB.

Banks can easily steal profitable ideas from each other (and almost always do). The Midland Bank had no patent on this trade. The main potential stumbling block was the central bank, the Bank of England, which wielded (and still wields) considerable regulatory power over UK banks, and might disapprove. The BoE did, indeed, notice that Midland had taken $50mm in U.S. dollar deposits in June 1955, and that the usual reason for this kind of transaction—financing commercial activity, like trade—seemed to be absent. Midland replied to the BoE’s raised eyebrow by mumbling that nothing sketchy was going on and the dollar deposits had been received “in the normal course of business”. The BoE had its doubts: Midland should probably have made a formal request under exchange control regulations; the interest rate paid for dollar deposits was high; the swap into sterling certainly went against the spirit of the BoE’s tight money policy. At the same time, Midland was technically within the law, and the transaction did have the benefit that it reduced the outflow of the UK’s dollar reserves in June from $56mm to only $6mm. And so they let it pass. As one official at the bank noted: “It is impossible to say to a London bank that it may accept dollar deposits but may not seek for them. We would be wise, I believe, not to press the Midland any further”.

(This pragmatic official, Maurice Parsons, was later Deputy Governor of the BoE and subsequently Chairman of the Bank of London and South America, BOLSA, soon to be a very active participant in the Eurocurrency markets. Another former BoE official, Sir George Bolton, who likewise played a leading role in Eurocurrency banking, was also Chairman at BOLSA, describing his role there as a “gamekeeper turned poacher”).

A year later, Midland’s dollar deposits were up to about $80mm. They were soon overtaken by other banks—particularly U.S. banks, whose London branches could compete for deposits unhampered by Regulation Q and make loans in the absence of the minimum reserve requirements prevailing in the U.S.. The further relaxation of exchange controls in 1957 – 1958 oiled the wheels still more. By the end of 1962 the American banks alone (nine of them by that time, and the largest single group in the market) had around $700 million in Eurodollar deposits in London. Good estimates are hard to come by, but according to one source, Eurodollars netted out to a little over $4 trillion by 2010, or roughly 24% of the total U.S. dollar banking market.

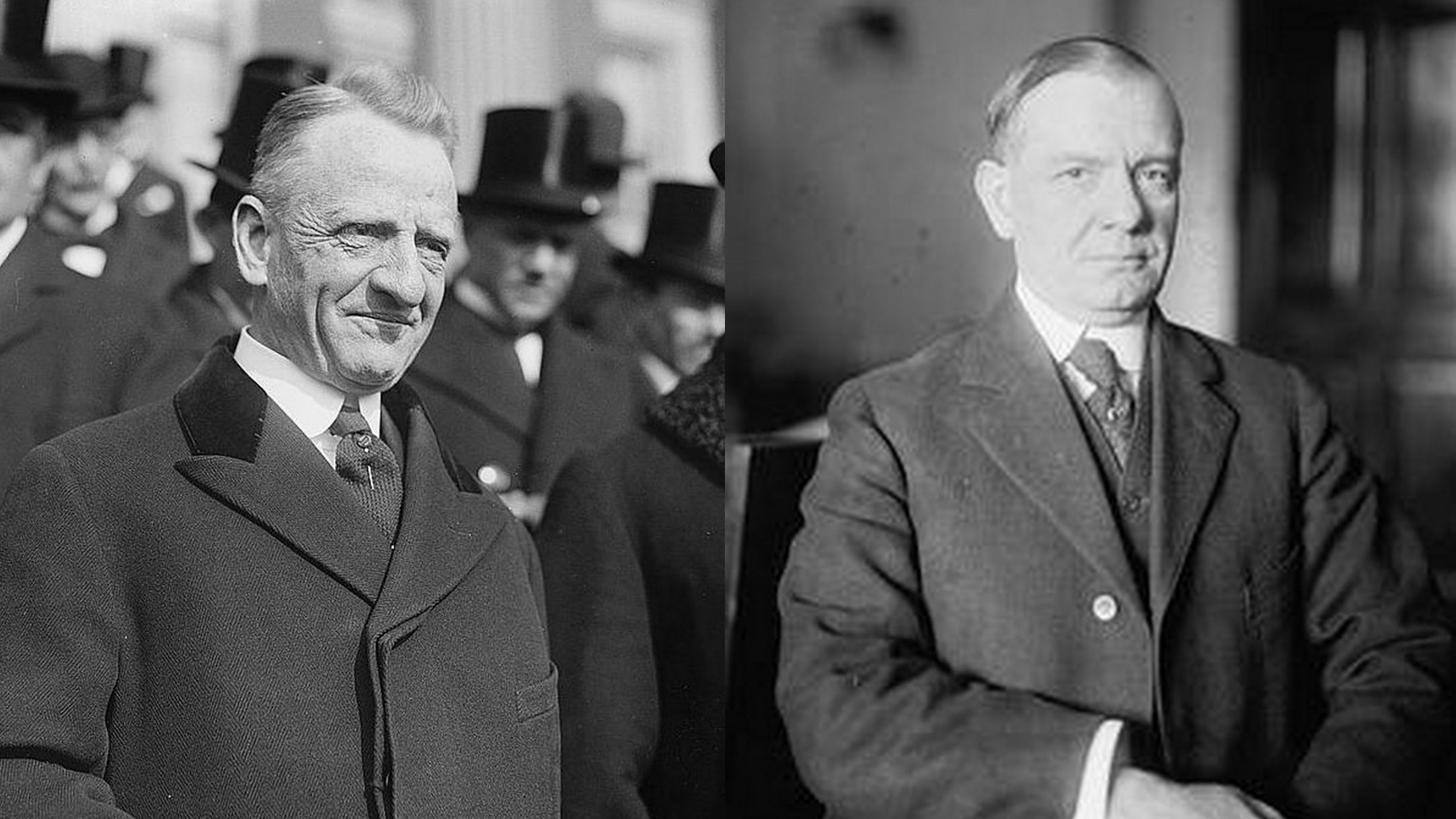

So thank you, says the City, to Messrs. Carter Glass and Henry B. Steagall, the original sponsors of the Reg Q legislation, by whose name the 1933 Banking Act is more commonly known.

From Eurodollars to Eurobonds

In the early 1960s the U.S. made another regulatory move which, in hindsight, seems almost to have been calculated to move international finance from New York to London.

The U.S. was then acutely concerned about “balance of payments problem”. For the ten years prior to 1957, outflows of dollars from the U.S. amounted to about $1 billion per year. (For perspective, multiply by about 32 times to get the same amount relative to U.S. GDP in 2018). But after 1957, the outflows accelerated to around $3 billion per year.

In today’s world of floating exchange rates, when currencies can adjust to restore balance, this calculation generally worries people less than it used to. But this was the era of Bretton Woods, designed to promote stability and prevent the competitive devaluations which had helped lay waste to the global economy in the 1930s: exchange rates were fixed against the dollar, within a narrow band, and central banks abroad were entitled, if they so wished, to redeem their U.S. dollar holdings for gold at $35 per ounce. Gold reserves in the U.S. amounted to about $23 billion in 1957 (somewhere in the neighborhood of 20 million tons) and had sunk to about $16 billion (14.3 million tons) by the end of 1962. At the rate of a $3 billion dollar outflow every year, the reserves could be completely gone in five or six years. In fact, it could happen a lot more quickly that that: if you added up all the dollars that were held by central banks abroad, the total was already far in excess of $16 billion, which raised the possibility of a run on the bank – the bank in this case being Fort Knox.

Strange though it may sound today, the U.S. actually ran a trade surplus at that time – about two to three billion dollars per year of exports in excess of imports (down from a peak of about $10 billion in 1947)—but the surplus was more than offset by other dollar flows. A good chunk of the overall payments outflow was from military spending abroad, with short-term lending, economic aid, and spending by U.S. tourists also contributing. A significant outflow also—roughly the same size as military spending—was private investment by the U.S. in foreign countries. Europe and Japan were growing rapidly in recovery from the war. Americans liked to invest in their stocks and bonds.

It was this outflow of investment dollars that JFK aimed to discourage when he proposed his Interest Equalization Tax in 1963.

On July 18th, Kennedy gave a long speech in Congress on the balance of payments situation. Among other things, he recommended implementing a tax ranging from 2 ¾% to 15% on American purchases of foreign securities. It was hoped that the tax would discourage Americans from financing foreign companies and thereby help stem the outflow of capital. The tax would expire in two years, by which time it was expected the BOP situation would have improved. In order to stop anyone trying to get in under the wire, he proposed to make the Interest Equalization Act retroactive to the date of his speech (except for issues already under registration with the SEC).

Andrew Smith [CC BY-SA 2.0] via Wikimedia Commons

Andrew Smith [CC BY-SA 2.0] via Wikimedia CommonsNot unexpectedly, Wall Street reacted coolly to the idea of profits curtailed. International markets were mostly bewildered, generally interpreting the move as a sign that if the dollar needed this protection it must be overvalued. Canada, the biggest foreign issuer in New York ($359 million in 1962, out of $867 million in total international issuance), quickly managed to secure an exemption, which prompted one skeptic to proclaim that the proposed tax was now “more hole than cloth”. Japan, the second largest issuer ($175 million) and badly in need of capital for expansion, was seriously perturbed, and the Tokyo stock market took a hammering in the two weeks after the announcement, including its worst one-day drop in history. The Japanese foreign minister came to Washington to try to negotiate an exemption for Japanese securities—unsuccessfully, as it turned out.

Regardless that some observers thought the tax bill would never pass Congress, the fact that it was to be retroactive killed foreign financings in New York stone dead from the day of the JFK speech. In November the Commerce Department announced that in the third quarter (beginning July 1st) the balance of payments deficit had shrunk to a six-year low, almost entirely because of the sudden complete stop in foreign financings, and that thirteen consecutive weeks had gone by in which no gold was lost from the reserves.

So where did these foreign companies, starved for capital, go to get funded? It’s perhaps not hard to guess: A New York Times article dated November 1st, 1963, three months after the JFK speech, was headlined “City of London Regains Status As Market for Raising Capital”.

There was a certain amount of pooh-poohing in New York regarding the ability of the European capital markets to match the liquidity, efficiency and expertise of Wall Street in international financings. The Joint Economic Committee of Congress early in 1964 opined that the collapse of such financings in New York was due to uncertainty brought about by the retroactive provision in the bill and that

If the bill is passed, there is likely to be a sharp resumption of foreign borrowing in the United States. It may well be that the interest equalization tax is more effective as a proposal than it would be as a reality.

The bill was eventually signed by LBJ on September 2nd, 1964 (with a scheduled expiration at the end of 1965), and the JECC turned out to be wrong in their prognosis. The Eurobond market grew at a sometimes breathtaking pace. Not just Japanese and European but even American companies began borrowing in London, so successfully that by 1966, London bankers were complaining that European and other potential issuers were being crowded out of the market. Issuance in Europe (mostly London) very soon far exceeded what had been achieved in New York in the years prior to the Act.

In lobbying against the bill a few months before its passage, one banker quoted in the New York Times had commented, “[W]ith this ineffective tax the United States is giving away on a silver platter its status as the leading financial center of the world.”

Indeed the move to London proved irreversible. And, while there were many other developments in the subsequent years, by 2007 Michael Bloomberg, Mayor of New York and no stranger to the world of money, was publicly worrying that London would soon take over from New York as the epicentre of global finance. [Naturally he could not have foreseen the curtailment of that expansion that is now likely to follow as the result of Brexit, or whatever Brexit-like thing happens over there and now where is it going to be—Frankfurt?! one bit there.]

So?

Attempts to control money and trade have sometimes achieved pretty much the opposite of what they were meant to achieve. Reg Q was intended to nurture banks in America and ended up driving a substantial portion of their business abroad; the IET was supposed to boost America’s balance of payments and instead destroyed New York’s overwhelming dominance in international finance.

The current regime is once again at odds with the rest of the world over trade and finance flows. More than any White House for many decades, this administration is using protectionist measures in an attempt to change the balance in favor of domestic industry. It is also aggressively flexing its financial and economic muscles in an attempt to achieve geopolitical strategic aims—by defaulting on the Iran nuclear agreement, for example, and reinstating sanctions against Iran. Students of economic history might ask whether these attempts, too, might backfire, and if so how.