I grew up rooting for Superman to beat Lex Luthor. I thrilled to see Luke Skywalker and the Rebel Alliance defeat the Galactic Empire. I loved watching Ellen Ripley beat the nasty xenomorphs over and over. As a young African American coming of age in the 1990s, I naturally gravitated toward John Henry Irons — DC Comics’ “Steel” — and the black heroes of Milestone Comics. Science fiction and comic books allowed me to think about a different world where I could dream of myself, an awkward and chubby boy, as being greater than the sum of my parts. But rather than caped crusaders or lightsaber-rattlers, I found myself most drawn toward a less fashionable hero: Captain Jean-Luc Picard, of the USS-Enterprise D.

While the inspiration for The Original Series had been the classic western, with James T. Kirk as the rugged white-hatted cowboy, the casting of British theatre actor Patrick Stewart for The Next Generation changed the framework. In the documentary Chaos on the Bridge, Stewart remembers asking the franchise’s creator, Gene Roddenberry, for guidance. Roddenberry handed him a stack of Horatio Hornblower novels, suggesting a new model of introspection and quiet dignity. Picard became a man who only fought when necessary, even allowing for his ship to take damage rather than fight back. He was comfortable with Shakespeare and Gilgamesh, using the latter story to forge a friendship with an alien captain from a species that communicated only through metaphor and archetype. Picard’s character could only have been written during an era of American confidence — a national swagger that touched much of the American identity in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Yet Picard, a Frenchman, did not “swagger” in any sense of the term. Unlike a DC Comics hero, he conducted himself with grace rather than power.

I was reminded of what his example had meant to me when, at the 2018 Star Trek convention, Patrick Stewart made a surprise announcement. “Jean-Luc Picard,” he said, “is back.” In a state of collective ecstasy, thousands of people took to Twitter to express their shock at just how much they cared about the return of a character who hasn’t appeared in anything new since the 2002 film Star Trek Nemesis. Perhaps this pointed to a hunger that pervades American culture: the desire for a hero who is complicated, all too human, yet still embodies a faith in humanity.

The captain of the Enterprise-D was the purest expression of Gene Roddenberry’s humanist ideals — namely, that one could cherish the various cultures that make up humankind and respect them all. Roddenberry had always aspired to make this ethic part of his vision of the future — sometimes clumsily, with occasionally heavy-handed parables in Original Series episodes, and sometimes admirably, as with the multiracial makeup of the original Enterprise crew. Picard was an expression of this ideal at the level of the individual. He was not only a warrior-diplomat and explorer, he was a historian and an archaeologist.

“There is no greater challenge than the study of philosophy,” Picard told Wesley Crusher, the youngest member of the Enterprise’s crew, conveying the importance of humanities courses at Starfleet Academy in the episode “Samaritan Snare.” To me, as a young viewer, it was an important message: learn all you can, and enjoy the challenge. Today, with the humanities continually treated as a luxury — or, perhaps worse, a distraction from programs in schools of business, engineering, or science that are assumed to be “more valuable” — Picard’s words are all the more pertinent.

Picard’s complexity reminded millions of viewers during Star Trek: The Next Generation’s heyday that we all contain multitudes. Following in his footsteps, Avery Brooks as Benjamin Sisko on Deep Space Nine and Kate Mulgrew as Kathryn Janeway on Voyager continued to expand the range of Star Trek’s commanding officers. Breaking from Kirk’s more traditional male heroism, Picard’s thoughtful, contemplative example allowed Sisko and Janeway to adopt some of those same traits. Picard’s humanist disposition became part of the Starfleet way. After his tenure as a Starfleet Captain, space opened up for an African American and a woman to succeed him.

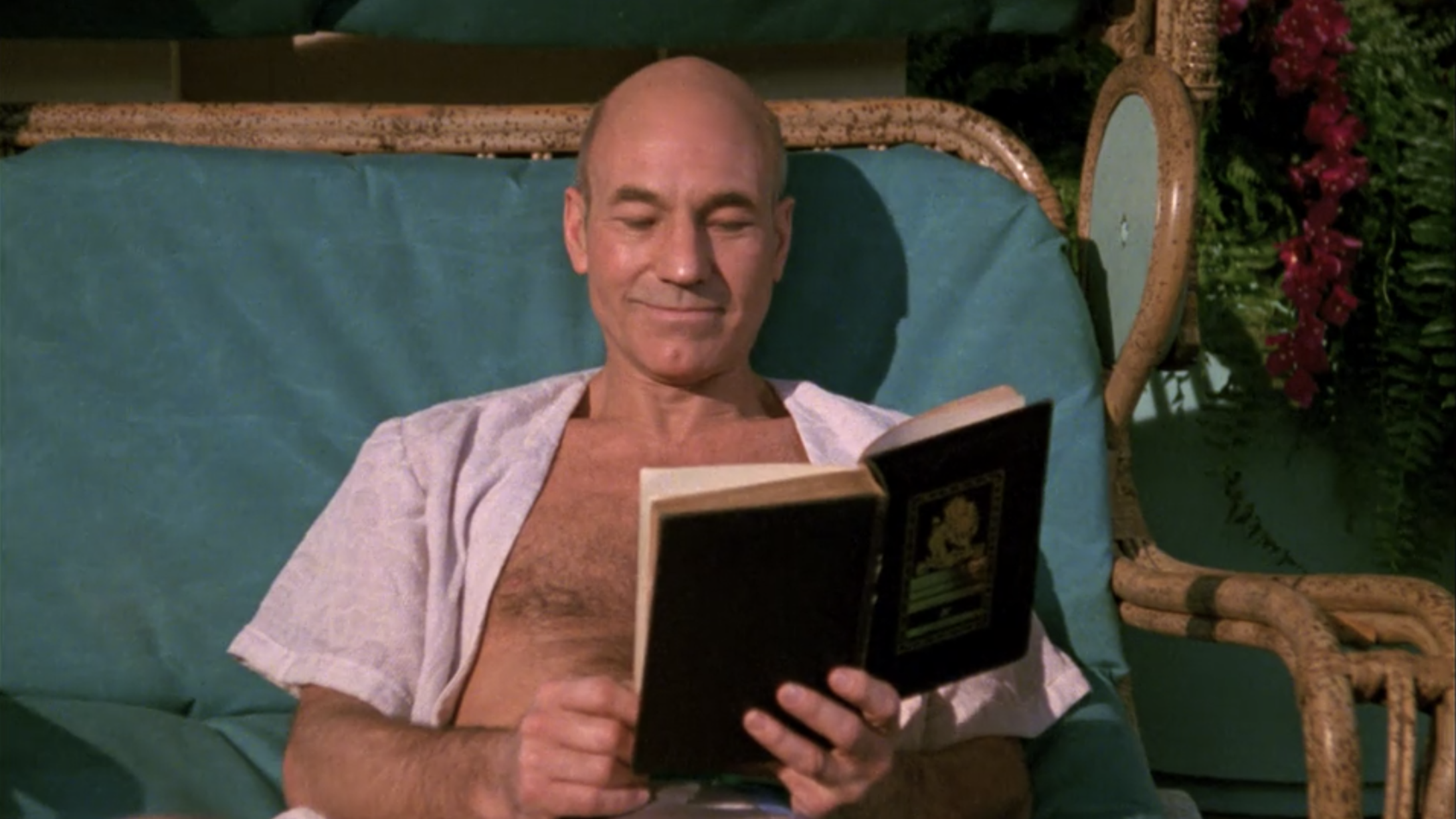

The mark of a childhood influence stays with you, and Picard’s example has continued to inspire me as a historian. Sometimes I imagine him gently encouraging my decision to stay home on a Friday night and read — though he would certainly also advocate living a full life, with the whole range of experience beyond logic and learning. The desire for knowledge lies at the heart of Star Trek, with its edict to “explore strange new worlds.” Picard showed that there is exploration to be done inside ourselves, as well as in outer space.

As television in the 1990s and 2000s became more cynical — producing charismatic anti-heroes and even sympathetic villains — a character so passionately devoted to truth and the refusal to allow might to make right began to seem even more out of step with the times. Even within the fictional universe of Star Trek, Picard’s travails seemed at odds with those of other Starfleet captains. Picard’s assimilation by the Borg in “Best of Both Worlds,” his torture at the hands of the Cardassians in “Chains of Command,” his experiences as the member of an extinct alien race in “Inner Light” — these stories gathered into an avatar of modern stoicism and humanism. Many fans were critical of the depiction of Picard as a standard-issue action hero in the Star Trek movies, showing how his ability to operate in a complex historical framework, and to use his brain in preference to phasers and photon torpedoes, were more than just character traits — they were expressions of a moral compass for envisioning the future.

Stewart himself has said that Picard would be a “man changed by his experiences” in the new series. We can only guess at what that will mean — and whether it will follow the deconstructionist bent of other resurrections in science fiction, such as Luke Skywalker’s in The Last Jedi. However, it’s unlikely Stewart would play a Picard as broken and irrevocably changed, in the way of his Charles Xavier in Logan — another dramatic example of a hero being broken down to his component parts before meeting defeat.

I hunger for Picard’s return precisely because of the optimism and dignity of The Next Generation. A little change to the character to reflect the passage of time — and, perhaps, a rougher Star Trek universe than we last saw in the 24th century — would make sense. But as we struggle to deal with the reality of a world where might and right are increasingly equated, a world back on the verge of possibly cataclysmic conflict between superpowers, I still hope to see him hold fast, in the face of adversity, to the humanistic spirit of reason and intellectual hunger.