My husband woke me at 8:00 a.m. on the day that Kofi Annan died. He was busy composing a Facebook post in bed, bringing his “public event-marking” tally since I’d known him to exactly three: our marriage, the birth of our son, and the passing of this famous Friday-born. Wandering downstairs to retrieve our eleven-week-old baby from his grandmother–with us for two weeks between her homes of Orlando and Accra–I naively thought that I might bring her the news. But as usual she had received it hours before, an urgent missive from a sister keeping watch now from Germany.

In the unlikely location of Baltimore, a Saturday morning in August became a day of personal mourning for a very public figure, in a mix of English and Fante, Annan’s first language. With pancakes on the griddle and goat soup in the fridge, we repeated stock phrases: “A fine man. A fine, fine man,” my son’s grandmother murmured, before I’d chime in with “A true abrantie,” the most common word in the Akan languages for gentleman, albeit cheapened now by use in Ghanaian fashion branding. We were living out a 90s multiculturalist ideal: biracial families communing around shared, earnest feelings toward bridge-building African heroes. But it had become hard to articulate that vision in anything but self-conscious terms. Perhaps this was part of what we mourned. If my mother-in-law’s generation could call Annan a “great” man, mine has learned to look askance at “greatness.”

AN EXCEPTIONAL MAN DOES NOT MARK A CONTINENT’S RISE, Twitter would tweet; DOWN WITH EXCEPTIONALISM. The reminders would be shared, shared again, quoted to gain likes with knowing aspersions. Annan’s mistakes in Rwanda; his liberal developmentalism; his blind eye toward his son’s financial hijinks. And then the coup de grâce, anticipated already by Perry Anderson in the LRB in 2007: Kofi Annan embodied style over substance. Style over system, really. No wonder “The West” loved him! An impotent pawn in an impotent organization.

This would be said. This would be said, and yet still Ghanaians would be mourning the world over. Some of them were in my kitchen, and one of them has my blood. I hope, then, to be pardoned for crying white tears (the worst kind, I know) that day for not one Fante leader I’d never meet, but two.

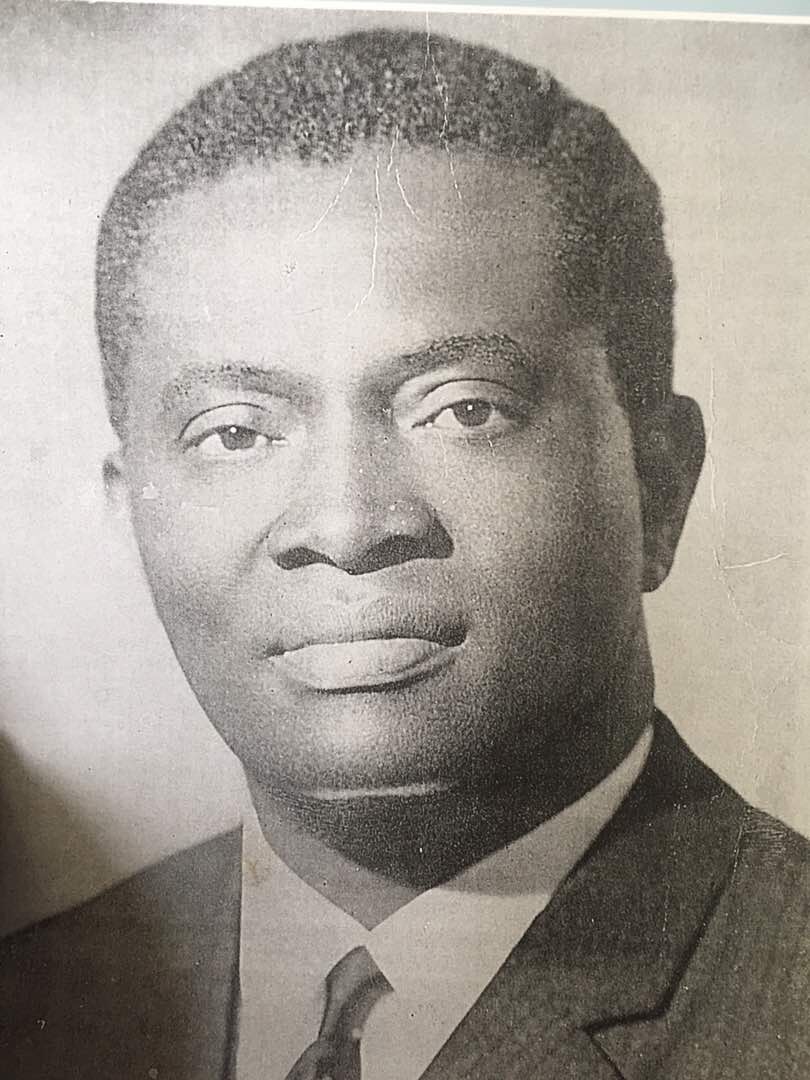

My father-in-law, David Eyiku Awotwi, died ten years before I joined his family, three decades after he served Ghana in Kwame Nkrumah’s cabinet.

What I know about him is this: he attended Kofi Annan’s high school, Mfantsipim, some twelve years before Annan did, though their paths later crossed a few times. He had a Master’s degree from the London School of Economics, and he was chief of the Elmina Fantes who lived in Accra. He was head of his anona or parrot clan, one of twelve such affiliations that are passed from father to child. (The parrots are known for their eloquence.) His own grandfather was the formidable Chief Kweku Andoh of Elmina, so formidable that—as Wikipedia tells me–there is now a Fante expression, Andoh nye woa?, that translates to “Art thou Andoh?” or, idiomatically, “Who do you think you are?”

“Andoh” is, thus, a middle name that joins men across generations of what is now my family. It is also an index for a kind of greatness that is inherited, that is part of one’s claim to cultural belonging, but which imposes expectations instead of entitlement. My son has this name, as do two of his uncles.

What I also know is that when I look at photos of Kofi Annan, I see my son’s grandfather, too. I am told that he read for hours each day, after starting his morning with a solitary walk around his busy neighborhood of Osu in a city, Accra, not known for walkability. (My husband once joined him, and was hit by a car.) “Culture,” capital C, was an essential part of the strict household educational regimen: “Classics” were assigned (my husband received Silas Marner, for which I don’t envy him); and there was a nightly homework table, whether or not there was any homework, with piano lessons a universal requirement. This was not in vain: one of his sons went on to become a composer. He opened a beloved movie theater in Cape Coast, called Top Yard; it was the first theater in the region, and we believe it still to be standing.

This is not to say that one Mfantsipim-educated Fante civil servant of a certain age is interchangeable with any other. Annan’s victories and failings are his own, and so, in a lesser key, are David Eyiku Awotwi’s. But Annan’s aura—his poise, his gravitas, the deliberate cultivation on display at the Manhattan salons he once hosted with his wife—has a source, and that source is shared. When people describe Annan’s famous comportment, they are invoking a cultural temperament that he exemplified but did not own, a Fante sensibility that sees learning not as mere bourgeois decoration, but as the path to a more just future. The Economist does not know this. The New York Times definitely does not. What they do not realize is that to mourn Kofi Annan’s passing for reasons of “style” is an unwitting historical homage, the unmarked recognition of a legacy dating back to the nineteenth century at least.

If this is not my legacy, not my stories to tell, it is and they are my son’s; if they are not, then they will not be anyone’s, very soon. But how do I transmit such a legacy to my child, as his primary caregiver, visiting his family in Ghana only once a year? How do I transmit to him the things about Kofi Annan that feel most redeeming, that have the most life, and yet have the least resonance among the intellectual subset–the Left commentariat, the academic critiquers and “subtweeters”–in which I am enmeshed? I would like to look at my son and say with a straight face that his grandfather believed things like “Knowledge is power, information is liberating. Education is the premise of progress, in every society, in every family.” (This is a Kofi Annan quote.) He did, after all. This was not just idle talk: David Eyiku Awotwi quietly paid school fees for a whole lot of people, not all of whom were relations, even liberally defined.

It’s difficult to say such things, even if they’re true; such truths are often hollow, or incomplete. According to all who knew him, my father-in-law believed in things that now sound naïve. He believed in individual responsibility in service of one’s community of origin; in a clear line dividing moral probity from wrongdoing that no amount of contextualization can move; in deep openness to good art and good people from any culture, of any race; in morality over profit; and in the mostly unsexy work of civil servitude. (I say “mostly” because he seems to have been fictionalized for a brief moment in an episode of The Crown, unbeknownst to its writers; as Kwame Nkrumah’s Chief Protocol Officer, David Eyiku Awotwi was responsible for arranging his visit with Queen Elizabeth.) He was not a revolutionary, though he was certainly a socialist by the standards of his time. His gender politics would demand a different piece, and his beliefs on child-rearing were stricter than ours, to put it mildly. But the essence of his person-hood, as it has been passed down to me, and as I live with it in his son, are there in the clips of Kofi Annan that have now found a new audience. In 2005, for example, Annan chided the Times journalist James Bone for “behaving like an overgrown schoolboy.” Still willing to talk, he explained, later in the exchange, “I think we also have to understand that we have to treat each other with respect.”

Imagine saying something like that now, and trusting that everyone in the room knows you mean it sincerely. Imagine living with my father-in-law.

Because I cannot imagine this, and because I have to, I turn to books. I turn to David Eyiku Awotwi’s own family genealogy, which, when he wrote it over the last decade of his life, he prefaced with a narrative that reaches back to Carl Reindorf’s classic History of the Gold Coast and Asante. “A definitive history of Ghana is yet to be produced,” my son’s grandfather writes, in part, because “that which has so far been recorded is mainly the product of foreigners who lack opportunities or the right contacts to access all the facts; or who also lack the objectivity need for assessing or explaining adequately the causes and circumstances of various events.” Reading his words, a foreigner lacking opportunities or the right contacts, I feel chastened. I keep on: “Then, above all, there is the acknowledged fact that history writing itself is an unending activity, forever requiring additions and updating.” The preface then envisions individualized yet collaborative historical documentation on a scale unprecedented in Ghana: It must involve “each and every one of us,” David Eyiku Awotwi entreats, “as individuals with our memoirs as heads of families, as heads or founders of hamlets and villages, as chiefs of communities, in towns, in districts, in regions, etc., all with their histories or traditions and as much of it as can still be remembered.” Kofi Annan’s family, I think, would be part of this too.

From here, I launch backward to an historical moment with which I’ve become obsessed, that of the short-lived but influential Fante Confederacy. In Western-authored obituaries, Mfantsipim becomes a generic “elite boarding school,” but it was founded in 1876 as an intellectual gathering place for Fantes, and this is a significant date: it is two years after the end of an historical experiment that is little discussed or remembered outside scholarly circles, that is, after the Confederacy’s self-declared independence from 1868 to 1874, six years of intellectual flourishing and highly effective anti-colonial organization. There are good books on this topic; Kwaku Korang’s Writing Ghana, Imagining Africa is probably the best one, along with Robert July’s The Origins of Modern African Thought. But in a nutshell, it was when a civic-minded, bicultural elite—what Korang calls civilizational “middle men”— tried to combine the best aspects of British governance with the best aspects of their Akan traditions. The Confederacy didn’t succeed in an immediate sense, though it cleared a path for the continued push toward independence. Its failure owes much to predictable imperial bad faith. The Fante and the British were allied in what is called the “Bond of 1844” against Dutch-allied Asante expansion. Fante leaders saw the British not as overlords, though, but as tenants, which did not go over well. When the British refused to allow the Fante to tax regional trade, the Confederacy went broke; its leaders acceded to being bought out by the British, swallowing their pride as they were annexed to the Gold Coast.

The high school that produced Kofi Annan and David Eyiku Awotwi represents the best of that era. Ghanaians will know that it was founded by John Mensah Sarbah, a Gold Coast lawyer, politician, and intellectual who also founded the Aborigines Rights Protection Society, along with peers like the writer and statesman J.E. Casely Hayford; many historians see this organization as laying the groundwork for Ghanaian independence in 1957. Casely Hayford, part of the selfsame anona or parrot clan at whose head my father-in-law once stood, also founded the National Congress of British West Africa, a decisive step in consolidating transnational resistance to British imperial rule.

Historians can and do disagree about the tactics, compromises, and successes of these groups and parties; like Kofi Annan’s tenure at the U.N., the details of John Mensah Sarbah or J.E. Casely Hayford’s leadership are open to any number of lines of questioning. But their aura is a tradition of its own, the self-justifying claim to Fante as a language of Culture, coupled with an abiding commitment to service in the form of no-nonsense anti-colonial institution-building. “If you took mankind in the aggregate, irrespective of race, and shook them up together,” Casely Hayford opines, through the loosely-fictionalized protagonist of his 1911 novel-cum-treatise Ethiopia Unbound, “you would find after the exercise that the cultured would shake themselves free and come together, and so would the uncouth, the vulgar, and the ignorant.” The book lays strong claim to being the first novel by an African published in English, and if it is easy, today, to hear the classism of those words, the elitism and patronizing scorn, it is much harder to hear how “cultured” also means non-racist, anti-segregationist, and public-minded. Cultured is plural, too: the book collates a dazzling range of literary, mythological, and historical references, spanning ancient Greece, imperial Russia, Japan, the Zulu, and the Yoruba, just some of the traditions with which “cultured” people should be conversant.

All elitisms are not created equal, and the Fante variant that binds Casely Hayford with Kofi Annan and my father-in-law is a different beast entirely to the “Africa Rising” millionaires who are now their successors. It is an elitism committed to proving its worth by nurturing institutions that help others to do the same. The Fante Confederacy legacy is one of virtue, not value in an economic sense; a cosmopolitanism rooted in a balance between reflection and community.

I watch the Kofi Annan tributes and take-downs and black-and-white photos roll in. I recognize someone I don’t know, but love. I arrive at a concept that I think will help me impart my own, textually acquired knowledge of my son’s legacy to him as something that, for others, is lived: I hope it will be lived for him, too. This merger of erudition and experience, for us, will take the form of ancestors.

This idea brings me a surprisingly intimate sense of peace. In Akan cosmology, the Ghanaian philosopher Kwasi Wiredu writes, ancestor status is not something given, but earned; it is the reward for a life lived through gradations of meaningful experience, defined by making “reasonable achievements in the direction of personal, family, and communal welfare.” Once granted ancestral status a person keeps permanent vigil, guiding the living but making few demands. For Wiredu, ancestors do not justify moral behavior, like the Christian God might be said to; they rather embody it and incentivize it in death as in their previous long lives. In this way, “ancestors can only enforce rules whose basis or validity is independent of their own wishes or decisions.” It is an oddly humble even as eminent role, geared toward years of steady, if not necessarily radical action.

My father-in-law, I am sure, is an ancestor. Kofi Annan has now become one too. “The African land of the dead … is not heaven in the Christian sense,” Wiredu continues. “The life of the ancestors is pictured as one of dignity and serenity, rather than of bliss.” Imagine entering what now passes for our public sphere and using a word like “dignity” in earnest, free from smugness or socially punitive undertones. Imagine proclaiming a belief in fair-mindedness, in a culturally expansive breadth of learning, in a world whose most powerful institutions seek fairness, too. Now imagine simply exuding these values, even if people are not sure quite how or why, or whether it’s not a stylish sleight of hand.

Whatever he did or did not achieve, an aura that inspires such a vision is the part of Kofi Annan that must be honored. I will honor it in him, in my son’s grandfather, and in the many figures across more than a century who brought it into view. Hopefully, one day, I’ll be able to honor it in my son too, in a singular but communally grounded, meaningful life.