Outside of Argentine Spanish, the word “piquete” is usually heard as a loan-word from the English word “picket,” as in picket-line; “Yo no cruzo piquetes” (“I don’t cross picket lines”), you might hear someone proclaim. But when #BlackLivesMatter protestors blocked the 880 freeway in Oakland in 2016—or when #abolishICE protestors set up 24/7 encampments in front of DHS/ICE headquarters across the US—Argentine journalists and pundits naturally recognized these actions as “piquetes,” and used the name as though it were a universal term for a general strategy, like a general strike or walkout.

They meant something different than “picket lines,” or even a tent-based occupation (“acampe”) or a roadblock (“bloqueo”). What they saw was something that can snowball or endure unpredictably, a spontaneous and headless protest movement that turns a public space into an emphatically contested one. If a picket line is a clear and unambiguous sign in labor’s hard-won vocabulary of protest, an Argentine piquete is less predictable, less coherent, and more disruptive; rather than a strategic inconvenience, a more unsettling attack on the Order of Things itself.

Piquetes take different forms. Maybe they’re burning tires and wearing hoods or maybe they’re intimidating local police by practicing self-defense protocols for the TV cameras. Maybe they’re just BBQing in the city’s main plaza, singing children’s songs, and serving as a free (outdoor) daycare center for employed comrades in the neighborhood. But when they put their feet up, they might be hanging their rain-soaked socks on a line spanning an economically-crucial rural highway that hasn’t let a car through in six days. A piquete rarely has a clear relationship to any conventional political party or movement, and the relationships between them are as contingent as the solidarity between unions. These spectacular and grandmother-terrorizing displays of incivility strive for disruption, not communication; an equal and opposite disruption to the union-dissolving hijinx of Uber, AirBNB and Silicon Valley venture capital, originating halfway around the world but very much raining fire on their backyard now.

The piquetero brand of disruption might be as portable (or “scalable”) as the Peter Thiel variety: the amorphous and largely anonymous “piquetero movement” of the mid-90’s was, in fact, a major inspiration for the Zapatista, the WTO-protest, and the #occupy movements. But as an Argentinian, I still want to claim that the origins of the piquete are as Argentine as Borges reading a British translation of the Quixote in his father’s library; it’s an Argentine invention to be placed in our list of contributions to world history alongside the ballpoint pen, the helicopter, the Hand of God kick, fixed-route public buses, and pedestrian traffic lights for the blind.

While its exact origins are unclear, the consensus is that the piquetero movement dates to a specific conjunction of economic and political factors in the early 90’s. The fall of the Berlin Wall triggered a domino effect in world politics, as many of the contingent and pragmatic coalitions between the center-left and far-left came apart throughout the developed world; as pro-business regimes increasingly took power, they abandoned many of the key concessions that kept labor and the left on board with the cold-war economic consensus. In Argentina there was a particularly sharp break, exacerbated by the upheavals of neoliberal precarity under Carlos Menem’s first term; Menem’s austerity measures shored up what was left of the middle class, but in his relationship to foreign capital, he was the first truly neoliberal president; in a dramatic break from Peronist tradition, he openly antagonized the trade unions that had maintained stable working conditions for the industrial class since the second world war.

Argentina’s working class has been heavily unionized—and relatively radicalized—for a long time. In the mid-19th century, entire mines and massive estates were staffed by boatloads of huddled masses from Basque Spain, Cataluña, Italy, Eastern Europe, and Germany; Argentine capitalists would kick themselves for not realizing how many of them had been pre–organized under red and/or black flags in their countries of origin. They infused native (and indigenous) traditions of resistance with a more distinctly international radical playbook.

Anarcho-syndicalism was a particularly strong note in this blend of radical currents, for example, with its anti-State distrust of (bourgeois-led) political parties and electoral politics. Many of the “free libraries” and open universities founded by Argentine anarchists in the 1920s remain, some having operated continuously for a century. Waves of military repression in the 20th century—even the open-season campaign against radicals during the dictatorship period—never fully purged Argentina of this tradition, however tame things may have looked through the 70s and 80s.

With the transition to democracy and a cash-strapped peace, the unraveling of old political coalitions reversed of once-untouchable concessions to labor. And as the center and the right grew chummy and austere, the ground fell out from under key export markets, making foreign capital scarce and leaving unionized industries high and dry. Some unions were desperate enough that they re-opened shuttered factories, running them as cooperatives, many of which still operate today as hybrid communes, community centers, and worker-owned businesses. New economic realities created new movements from the ground up, and people with experience of direct-action and worker-led organizing bubbled up into leadership positions, grabbing the mic when a TV crew showed up at a worker-occupied factory or a highway cut by an encampment.

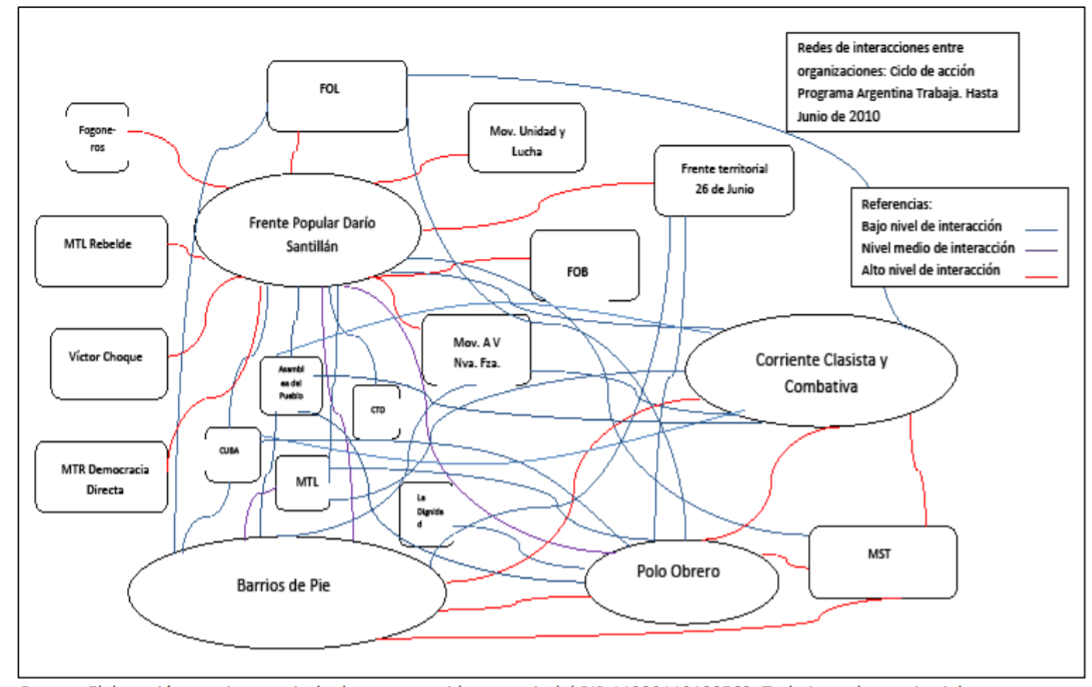

If anything, what defines this highly amorphous coalition of radical movements is its hostility to bureaucracy or to being fixed in a straightforward “platform” or public membership roster. Many piquete groups are dramatically anonymous, with protestors wearing matching hoods or bandanas. Protest signs juxtapose Karl Marx or Che Guevara with a martyr gunned down by local police, and yet there might be a Quilmes logo in the corner; manifestos often comingle nationalism with internationalism, Peronism with resistance to political parties, as well as anarchism, communism, and trade-unionism. The National Piquetero Bloc has public leaders and publications, but other key groups include the decidedly grassroots Barrios de Pie (Neighborhoods Standing Proud), the more anonymous and decentralized Quebracho Movement (named after a native tree whose name is Argentine slang for “dead-broke”) and the CCC (Combative Class-warfare Current), a Maoist group that evolved out of the student union movement but now works mostly in unincorporated slums. Tracing the history of the movements, or even the boundaries between them, is sufficiently difficult and confusing to make journalism on the subject an exercise in polemic and shade. When a sociologist working with the prestigious CONICET research cluster published a detailed account of this thicket of organizations, her attempt to chart out the key players didn’t so much clarify the structure or genealogy of the movements, as their constitutive confusion:

Far more important than any (inevitably elusive) family tree of ideological influences and interactions between the groups is their shared material reality. These are neighborhood (and favela) organizations that generalize the protest culture of the labor movement, turning it towards more extreme ends. The piqueteros and piqueteras—or, since it is 2018 everywhere, even in the favelas of South America, the piqueterxs—protest the State for placating working-class resistance with mollifying welfare and domesticating bureaucracy; they protest traditional labor unions for being too easily corrupted and co-opted. They protest Corporate Capitalism itself, rather than specific capitalists or corporations.

You can imagine how the mainstream press refers to these lumpen-protestors, or how upstanding middle-class citizens use the term “piquete” to dismiss politics that stray too far from electoral agendas. It’s a much harsher dismissal than American terms like “pinko” or “wobbly,” which get bandied about with a winking irony or a historicist reverence; instead, it borders on something closer to “terrorist” or “hooligan,” a nuisance at best and a moral unspeakable at worst.

The movement is not leftist in a classical sense of making civil society accessible to workers, or redistributing wealth: they seek dignity and full citizenship for a population remaindered by the economic upheavals of globalization. Most would be happy simply to have their status as “working poor” restored. Piqueterxs names the people rendered superfluous when a transnational corporation shutters a factory and turns an entire neighborhood (or even a whole county) into a giant unemployment line.

As factories were closing in the 90s, the social safety net in Argentina was slashed to placate what little foreign capital remained in the country. The Polo Obrero, a key piquetero organizing group, started as a branch of the Partido Obrero, a small but historically significant working-class Leftist party with nationwide electoral reach. As piqueterismo became its own phenomenon, it’s gained a measure of autonomy. After all, you’re not really an “obrero” (“worker”) after your job is eliminated. Thus Argentina has seen membership in so-called “unemployment unions” flourish, as traditional union membership has stagnated; the piqueterxs have the difficult task of galvanizing the growing jobless portion of the labor force, a depressed and unstable demographic..

However quickly some dismiss them as clamoring for handouts, the piqueterxs are less interested in redistributing wealth than in redistributing employment, in ways that might expand the conversation internationally. The demand for a 30-hour workweek, for example, is baffling on its face, but provides an insight into the piqueterx imagination of a re-distributed economy. Capping full-time employment at 30 hours/week would force more people to be hired “full-time” with benefits, even if at lower wages per person. Employers in Argentina as everywhere are increasingly breaking up full-time positions into gigs for independent contractors (which in Argentina, as in most places, people glibly call “uberization” when “precarization” sounds too academic). Macri, who before becoming a neoliberal president occupied himself with bumbling around my home town impersonating a Big Time Businessman and idolizing the great Cheeto Debt-Wrangler of the North, has repeatedly tried to get legislation through Congress that would facilitate more independent contracting and weaken the definition of full-time work, which his mainstream opposition might not have been able to resist successfully without piquetero mobilization on the ground.

The age-old leftist truisms about the dignity of work take on a strange new character in our globalized world of automated labor, as unemployment becomes an epidemic while Hoovervilles spring up alongside half-empty luxury condos. In response, the piqueterxs are not asking for work to be dignified or even justly paid; they demand shelter from the indignity of generalized joblessness, an end to state complicity in the conversion of entire industries to precarious on-demand/at-will contracts, and for a livable form of the existing experiments in universal income. (Side note: Argentina’s severe currency fluctuations over the last century makes minimum wage and universal income legislation very complicated, as this story from Thursday makes clear.) If the piquetero form of protest sprang up first in Argentina—because it was one of the first countries of the Global South to see a stable labor movement and industrial population downsized in the span of a decade—it’s only because every wave has to strike somewhere first; the conditions are general, and if you don’t believe me, ask your next Uber driver what they did before they drove home drunk people for a living.