The walk from the parking structure to the hotel reception desk involved crossing a vast exhibition floor. It was empty, due to the late hour, save for the late-model sport utility vehicles that glistened and glowered on display pedestals. It appeared that something called Bushmasters was gathered here for its annual convention.

“What’s Bushmasters?” I asked the young woman checking me in. Her name was Kailey.

“I’m not sure. But I know they’re selling weapons.”

She busied herself at the terminal. High on the wall behind the desk were five life-sized dolls, apparently made of straw and fabric, in rustic peasant garb. They had flat faces and empty stares. Four were white, one Black—a predictable ratio, I suppose, for a convention center in Alabama. They looked like a sinister tribunal.

I asked Kailey, “You have to work with them watching over your shoulder?”

“I try not to think about them,” she said.

You can pick your own context when you go to Montgomery to visit the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, dedicated to America’s thousands of known and unknown victims of racial terror lynching, which opened on Cottage Hill above downtown earlier this year. Your focus might, for example, be current and national; you might be concerned with the erasure of racial terror from American history, and with the direct lineage from lynching to racist policing and the prison-industrial complex. The Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), the valiant non-profit led by Bryan Stevenson, built the memorial and the Legacy Museum, located downtown, in part to insist on this connection.

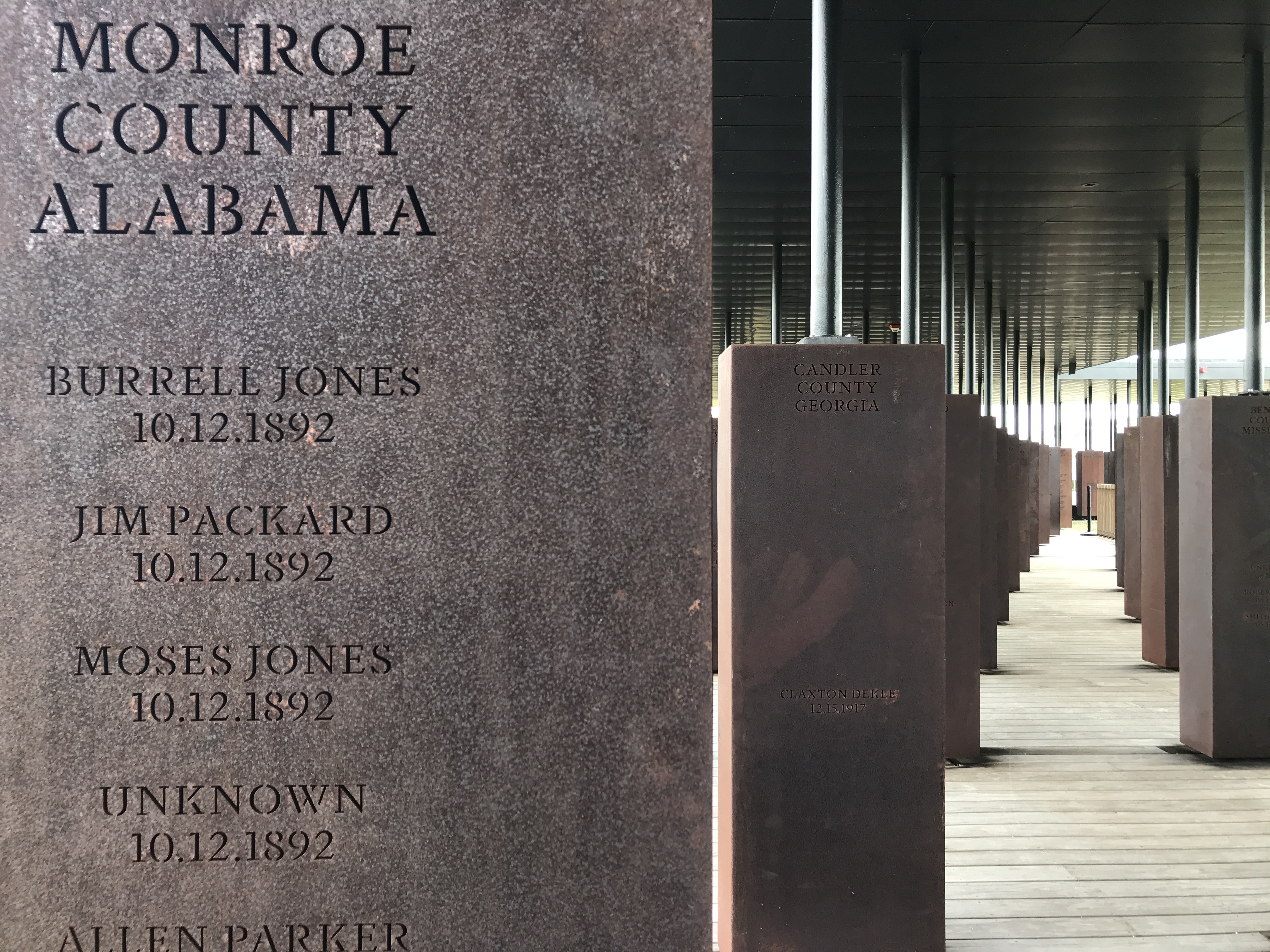

Perhaps you descend from a family that experienced or fled from lynchings—or perhaps an ancestor was a perpetrator. You may have come to find the steel pillar at the memorial dedicated to your home county, with the names on it of every lynching victim whose identity could be double-confirmed by a rigorous research process. Perhaps you have heard that the EJI has invited each county to face its history and honor its dead by collecting and displaying the duplicate pillar prepared for that purpose.

Or perhaps the context picks you, such as when you land at the hotel that you chose for its central location, and you find it turned over to the Bushmasters—a national organization for deer hunters, as it turns out. Opened in 2008, at the corner of Commerce and Tallapoosa, four years after the riverfront stadium for the minor-league Montgomery Biscuits, the hotel and convention center are part of an aggressive effort to redevelop the city’s downtown. They belong to the Retirement Systems of Alabama, the parastatal agency in charge of pension funds that plays an outsize role in Alabama’s economy with its unusually large amount of direct investments, and around which swirls the odor of cronyism and mismanagement.

If the hotel feels vaguely haunted, it might be because it sits on a parcel where several slave traders had their offices. Indeed, the trade for which Commerce Street is named was largely in enslaved persons. Montgomery was a hub of this trade from around 1820 to the Civil War, as steamboats delivered enslaved people for sale and distribution across the plantations of the Black Belt. They were marched up the street from the docks on the Alabama River to the market in Court Square. The EJI’s office is at the site of one slave warehouse, and the Legacy Museum is in another, around the corner.

Until recently, Montgomery’s boosters have preferred to emphasize the heroic, redemptive history of Rosa Parks and the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, where the bus boycott was organized, in telling the story of the city’s role in America’s racial history. The opening of the Memorial for Peace and Justice has shifted that public history, giving it a new, undeniable center of gravity in the solemn edifice at the top of the hill.

It really should have been public, and free. But since it took a private entity to conceive, fundraise, and build this acknowledgment of our national shame, there is some rigmarole at the entrance—a small fee, but cash is not accepted; you are encouraged to save through a joint ticket for the museum, but it must be purchased online. There is also a metal-detecting portico and wand inspection. There are people angry that this memorial exists.

The power of the place takes over once you step onto the grounds. Simply put, the memorial’s design—by the Boston-based collective MASS Design Group—is a triumph. Its organizing device is suffocatingly strong. The pillars begin set on the ground like trees in a forest, then rise up as you advance, suspended from the ceiling as the floor slopes down, growing denser all the way. But more than how many were lynched—there are roughly 4,400 identified here, killed between 1877 and 1950, but we know there have been many more—what strikes you is just how much was lynching: the prevalence, the normality, and how denial of humanity accelerates violence into frenzy.

Most of all, it forces implication. As I walked through the hangar-like space, taking photographs to serve as visual notes as I always do, my arm grew heavier as the pillars lifted off the ground and rose above my waist, my shoulders, my head.

At what point can you still photograph without being the spectator? At what point can you still look?

It was morning, still quiet. I chatted with William, a docent in an EJI t-shirt. He pointed out details. The pillars are made of corten or weathering steel, an alloy used for shipping containers that “bleeds” as it oyxdizes, forming a protective coating that regenerates. The gentle discoloration that results is already making each pillar unique, underlining how each county’s history—each documented event, really—is distinct. Microdots of moisture, tinted by the metal, form dark spots where they drip onto the floor, amplifying the relentless patterning.

Whenever another lynching meets the researchers’ standard—double-confirmation from credible archives and contemporaneous sources—the corresponding county pillar will have added to it, by waterjet inscription, the year and the lynched person’s name.

The docents have a sensitive job. Visitors can get overwhelmed and slump into fetal position. One man who opposed the memorial arrived intent on picking a fight and nearly caused a brawl. But between the extremities, there is constant teaching and learning, William told me. Many visitors, upon locating a relevant county pillar, cannot help but share with the docents their hometown history or family lore.

August heat. A growing crowd on the grounds. Gossiping adolescents amble past the rust-toned duplicate pillars that lie on their side awaiting county inquiries. Three middle-aged women insist I not miss the Rosa Parks Museum. There are a few sculptures set on the lawns around the memorial: Kwame Akoto-Bamfo’s enslaved Africans in chains, Dana King’s statues of women in the Montgomery Bus Boycott, Hank Willis Thomas’s heads and raised arms emerging from the top of a cement wall. Hands up, don’t shoot. Each would make a strong intervention elsewhere—perhaps on Wall Street, instead of that annoying “Fearless Girl”—but here they feel additive, a little perfunctory.

Back downtown, the Legacy Museum serves a vital message, but it’s cramped, dense with didactic materials, regimented by timed-entry ticketing. It’s hard to stay long. On the hill, though, there is space. A grassy patch at the center of the grounds is marked as Memorial Square, evoking town centers and courthouse squares where many lynchings took place. But this time you are looking out. In one direction is Cottage Hill, the bucolic neighborhood of historic houses laid low by white flight and pierced through by Interstate 65; with construction of the memorial have come quickening signs of gentrification.

In the other direction, through the hanging pillars and under the memorial roof appears the vista of Montgomery’s reinvented downtown, a skyline of banal business architecture topped by the logos of financial firms: BBVA Compass, Renasant, the RSA headquarters with its green pyramidal top. Money, after all, connects the phases of American racial oppression and terror, a fiber more durable than even prejudice or ideology.

From here, the palimpsest inverts. The dead interrogate the living dead. The ledger is open. There are balances to reconcile—pillar by pillar, county by county.