Tempelhofer Feld, the airfield of the decommissioned Berlin Tempelhof Airport, is one of the largest urban green spaces in the world.

The main entrance on the east end of the field, at the end of Herrfurthstraße, is hazardous: one must navigate bicycles, skateboards, stroller armadas, and the pedestrians who—drunk on sun and beer—walk in the street as long as possible before grudgingly giving way to cars. There is an area set off for barbecue, packed with families, bikes, hookahs, and stereos; the plumes of smoke give the scene the quality of a Bosch painting. In adjacent community gardens, you’ll see as diverse a mix of people as you’ll find in Berlin, smoking joints, picnicking, or watering and weeding their beds. In the distance, the half a sun still visible over the terminal has gone crimson, the sky around it a softening acrylic pink. The tops of the high grasses between the runways, roped off this time of year for nesting birds, move as an almost incandescent sea.

It’s the closest thing we’ve got to an ocean in Berlin: big sky and cool breeze in the middle of a metropolis.

***

Near the old terminal on the northwest end of the field is the largest of Berlin’s twelve container villages; over a thousand refugees live in so-called “Tempohomes,” separated from the park by a chain link fence.

The majority are from Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria, but they come from all over the Middle East, northern and sub-Saharan Africa, Turkey, the Balkan states, and the Caucasus. Many had previously been living in the airport itself, in doorless cubicles erected in the hangars as a temporary solution in 2015. The last moved into the Tempohomes in November of last year. Though new permanent structures were banned after a 2014 plebiscite meant to hinder the construction of luxury housing on the field, the Tempohomes are allowed through a 2016 change to the law passed by a coalition in the Berlin’s House of Representatives. Many see this as a test of how far the Volksgesetz (people’s law) against new construction can be bent; the Tempohomes are prefabricated containers brought in on trucks, with above-ground water and electrical hookups hidden under wooden gangways or stuck into planter beds on raised concrete slabs. Only temporary solutions are allowed: the container village must be gone by summer 2019.

Illegal, but tolerated: Tempelhof is a matrix of such coordinate clauses. It’s a park, but it has a fence, hours, and private security. It’s open to the public, but swaths of it are rented and fenced off for private events by a state-owned non-profit. Park rules prohibit most vendors, but this massive non-commercial space has had a transformative economic effect on the area.

Urban, but pastoral. Modern, but historical. Everything about Templehof is something different from what it was, and yet everywhere you look, you see the past resurfacing. You may find it uncanny. Or you may just have a beer.

***

I’m a junkie for postcards and advertising that invent a skyline by creating some impossible location on the ground, lumping the icons of Berlin’s history, survival, and reunification into a continuous panorama. But Berlin evades orientation. Its abject lack of a skyline is punctuated only by the respective former downtowns of East and West Berlin, the cartoonish Potsdamer Platz, and the occasional high-rise or church spire. The iconic Fernsehturm, the second-tallest structure in the EU, is visible from everywhere and looks the same from all sides. The city didn’t grow gradually outward from an old town; in 1920, with the Greater Berlin Act, it swallowed surrounding towns overnight, expanding from 66 to 883 square kilometers and absorbing Charlottenburg, Köpenick, Lichtenberg, Neukölln, Schöneberg, Spandau, and Wilmersdorf, along with swaths of countryside, all in one fell swoop. The 20thcentury saw modern Berlin born, bombed, cut up, and put back together, but it still has no center. The mythical origin point is a well in the bizarre Nikolaiviertel, an East German concrete-slab fantasy of old Berlin, built for the city’s 750th birthday in 1987.

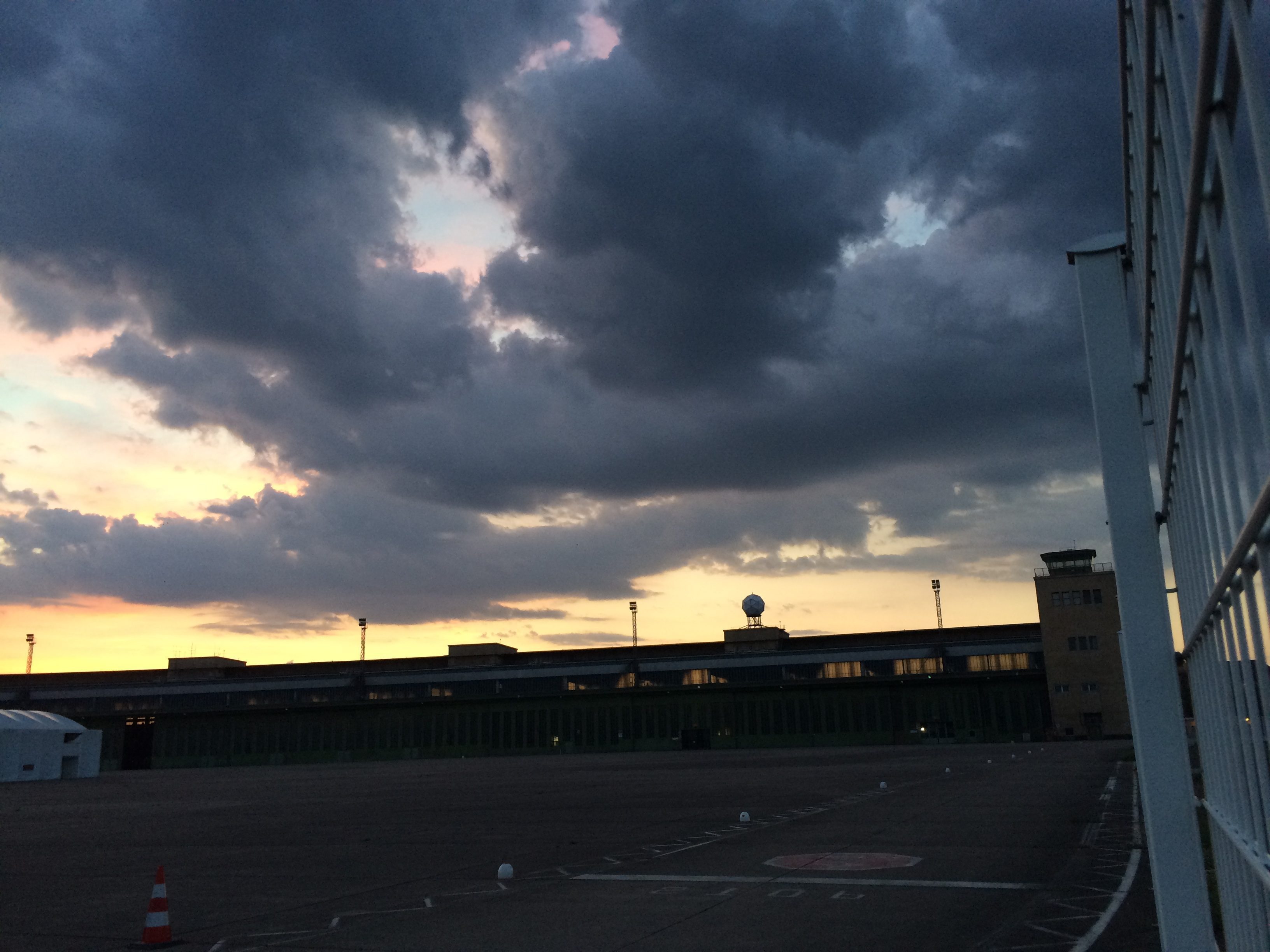

You can, however, get a view of Berlin from Tempelhof, Nazi architect Ernst Sagebiel’s sweeping masterpiece of the so-called Luftfahrtmoderne (aeronautical modern). The sign above the old main doors doesn’t say Templehof, but Zentralflughafen, or central airport; its mythical status at the center of Berlin the metropolis offers a view of a city in which—to borrow a line from novelist Daniela Hodrová about her native Bohemia—the knot of history has been tied more than once in the 20th century.

Like so much fascist architecture, Tempelhof was built for dramatic views and vistas; it was to be a symbol of Berlin, the great metropolis of the future, rising from the ashes of the war. The way the limestone facade catches the sunlight evokes the “temple” in its name, while the streamlined windows broken up by narrow pillars, all divided by looming towers, give it the feel of a fortress by night. Its austerity is aggressively modern, however; the ornate marble floors and high windows of the main hall are as sleek as they are imposing.

When I took a tour of the building last month, my group stepped out of the unfinished stairwell onto the roof and everyone went quiet. Our guide pointed to the wing-like hangars radiating off the terminal, where, along the length of the roof, you can see what look like gradual steps. A main function of the building’s shape is to allow for these galleries, so people could watch planes or events here on the airfield. “A personal order from Hitler,” she added, and I can’t stress enough how curtly she tagged on that little tidbit.

Most famously, perhaps, Tempelhof was the site of the Berlin airlift, and the US military maintained a presence there until 1993. But the military history of the site goes back to the 13th century, when the Knights Templar used the area as a local headquarters. In the 18th century, the field was a parade ground for “the Soldier King” Friedrich Wilhelm the First, and at the turn of the 20th, the military began using it for experiments in flight (Orville Wright flew his plane for 150,000 people in September 1909 and Hubert Latham completed the first overland flight in Germany a month later).

On May 1st, 1933, approximately one million people converged on the field for a mass rally celebrating “The National Day of Labor,” the Nazis’ völkisch reinterpretation of International Workers’ Day. Hitler delivered a speech to the assembled Berliners, along with brigades of the military, SS, and SA (who raided trade unions and arrested organizers the next morning). Also in 1933, the only officially-designated concentration camp within Berlin city limits was established, in a former barracks, and used to hold dissidents, leftists, and men arrested for homosexuality until it was closed to make room for the construction of an airport.

The hangars of Sagebiel’s building form the wings of an eagle taking flight; the glory of the Thousand-Year Reich was to manifest itself as much in its architecture as in its technological progress and the collective might of its people. Along with Werner March and Albert Speer’s Olympiastadion, the airport was to have been one of the opening moves in the transformation of Berlin into Germania, the Reich capital that Germany—after winning the war—planned to build as architectural marvel that would put Imperial Rome to shame. “As world capital Berlin will only be comparable with Ancient Egypt, Babylon, and Rome,” Hitler declared. “What is London, what is Paris compared to that!”

The Nazis never used Sagebiel’s building as a civilian airport, turning the airport over to arms manufacturing in 1939 (specifically the Junkers Ju 87 dive bomber). When you stand at the fence by the Tempohomes, you’re standing where thousands of forced laborers from across Europe were housed, Jews, Poles, skilled workers from Italy, the Netherlands, Belgium, France, and Czechoslovakia, as well as Soviet POWs.

***

When Tempelhof was decommissioned in 2008, it was to have been the first stage in the building of a new German metropolis, a new vision of Berlin rising from the ashes of history. Berlin’s other two airports—Tegel (TXL) and Schönefeld (SXF)—are both also slated to be closed when Berlin Brandenburg (BER) is finally finished, a single airport for the singular, reunified Berlin that planners began to envision soon after the fall of the Berlin wall. But history’s page has been a long time in turning: with ever-climbing costs and endless construction failures, BER has become shorthand for mismanagement and inefficiency.

Instead, the knot of history is tied once more. Templehof’s transformation into a park, for example, has catalyzed the gentrification of the northern part of the borough of Neukölln and Schillerkiez, the neighborhood directly to the east, which was once perpetually buzzed by planes; in their absence, rents have gone up 121% since 2009. The narrow streets are increasingly full of coworking spaces, hip bars and restaurants that come and go, and the global citizens of AirBnb. Berlin has long been perceived as dirtier, poorer, and more dangerous than Germany’s other big cities, and you can still go clubbing at 10 am, but speculation is ravaging an already insane housing market. You can see the changes wherever you look. The (largely) minority-owned Spätkäufe (late- or all-night convenience stores) are being targeted under Germany’s weirdly-Christian Sunday shopping laws, and on the site of the razed East German Palace of the Republic, they’re rebuilding a gaudy Prussian castle to house an ethnological museum full of colonial plunder.

Follow the signs placed around the field. Take a €15 tour. Tempelhof endures, not as a relic or historical anomaly, but as a monument to historical continuity and repetition. But if you are barraged with uncanny historical resonance, its paradisiac improbability begs you to chill out, have a beer.

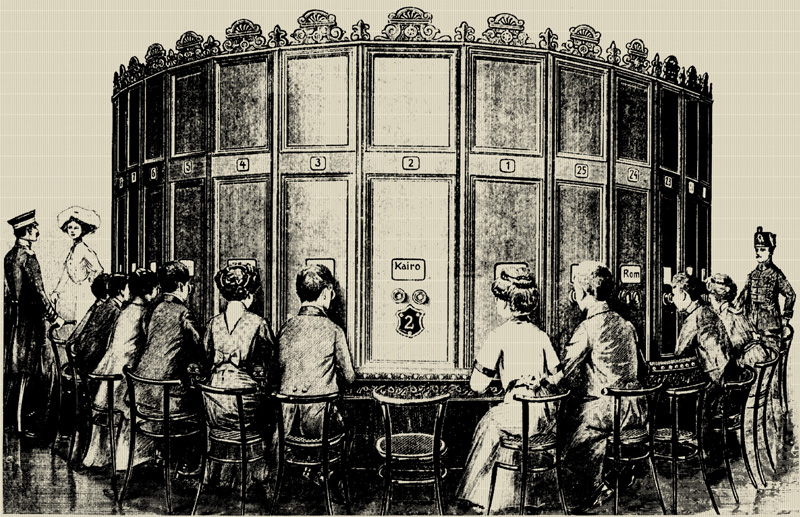

In his sketches of his childhood in Berlin, Walter Benjamin recalled the Kaiserpanorama, a staple of popular entertainment at the turn of the 20th century. Viewers would sit around the massive cylindrical machine and stare into the peepholes, as enchanting stereoscopic images—of faraway colonies, the hulking new ships of the Imperial Navy, Berlin’s own civic grandeur—cycled by. One aspect of this picture play disturbed the young Benjamin: “This was the ringing of a little bell that sounded a few seconds before each picture moved off with a jolt,” he recalls, “in order to make way first for an empty space and then for the next image.”

The Kaiserpanorama shows us the world in an uncanny sequence, as seen from a static position of power—specifically colonial power—mediated by the hypnotic ring of the bell. The world moves by in neat intervals, but when the first image inevitably reappears again, you may ask yourself, under the spell of the machine, “have I seen this before?”

For all the work the Nazis put into this building, my guide told us, this emblem of the Thousand-Year Reich had never been meant to last very long. They wanted to build a new, massive airport south of the city, probably not far from where Berlin Brandenburg Airport is (still) under construction. As for Tempelhofer Feld—whose original owners, the Knights Templar, used the profits from farming the place to fund their own adventures in the east—the Nazis had planned to turn it into a park.

Have I seen this before?