The United States spent several hundred years draining its swamps. Somewhere beneath all that water, Americans knew, was solid ground. So lush tracts like the Great Black Swamp, in northern Ohio and Indiana, were turned into farm fields; cypress bottomlands along the Mississippi River dried up behind levees, their old-growth trees harvested for timber; the Everglades became a toxic afterthought in the midst of the Florida land rush. Following European arrival on the continent, half of all wetlands disappeared from the contiguous 48 states. Swamps became subdivisions, airports, shopping malls, marinas, suburban business centers, interstate highways — with rippling effects for both wildlife and, finally, human life.

Slowly, over the course of the 20th century, the scope of the damage started to become clear, and in 1989 President George H.W. Bush announced a new plan for wetlands protection. Quoting the ecologist Aldo Leopold, Bush promoted the initiative in front of an audience of Ducks Unlimited members in Arlington, Virginia. “It’s time to stand the history of wetlands destruction on its head,” he said. “From this year forward, anyone who tries to drain the swamp is going to be up to his ears in alligators.”

That was then. Now think of the last thousand times you’ve heard a politician talking about wetlands. Though Donald Trump has made it into a catchphrase, he didn’t come up with the metaphor “drain the swamp” — socialists coined it in the early 20th century. To drain the swamp meant to eradicate the parasites on public life, whomever you considered a parasite to be: Mother Jones wanted to drain the swamp of capitalist bloodsuckers. Later, Ronald Reagan wanted to drain the big-government swamp, and Donald Rumsfeld wanted to drain the swamp that supported terrorism. In the 2000s Time magazine had a politics blog called Swampland — the nation’s capital serving as a common reference point for those wanting to drain some swamp or another.

Still, the “swamp” will now belong to Trump forever, he being the one who, as Joan Didion wrote about lovelier affinities, “claims it hardest, remembers it most obsessively, wrenches it from itself, shapes it, renders it, loves it so radically that he remakes it in his image.” The MAGA artist Jon McNaughton, like a fascist Thomas Kinkade, made a painting of Trump crossing a swamp modeled on Washington Crossing the Delaware: Trump holds the lantern, Pence the flag. So closely associated is Trump with the language of the swamp that his detractors, too, have now adopted it full-heartedly. “Elizabeth Warren Has Bold Ideas About How to Drain the Swamp,” the Nation announced, touting the senator’s anticorruption program. “The swamp has never been more foul or more fetid than under this president,” Chuck Schumer said. The New Yorker launched Swamp Chronicles, a series of investigations into the president’s dealings. Even Rebecca Solnit, a writer acutely interested in nature and the nuances of language, summed up Trump’s offenses to date as “the thicket or the swamp or whatever filthy thing we just swam across,” in an article under the subhead “The Swamp Is Not Going to Drain Itself.”

What do these people think a swamp is? What does Trump? It’s useless to wonder what the president “means” by any particular locution, of course, but the widespread embrace of his awful rhetoric is a bit disheartening, suggesting a shared alienation from the natural world. It bespeaks an impoverished collective imagination that “drain the swamp” can represent an act of cleansing rather than a catastrophe — which, ecologically, it is. The phrase emerged when swamps were thought of as little more than alligators and malaria, but they’ve since been relieved of that bad reputation. They’re now called wetlands and recognized for their biodiversity, as a landscape that enhances our experience of being in the world rather than impedes it. An obvious joke, but a true one: comparing politics to a swamp is unfair to the swamp.

There’s a sense, though, in which the phrase is an apt description of what Trump is up to. This sense goes back to the beginnings of the republic — indeed, to the European invasion of the continent, which inaugurated a centuries-long program of wetlands destruction.

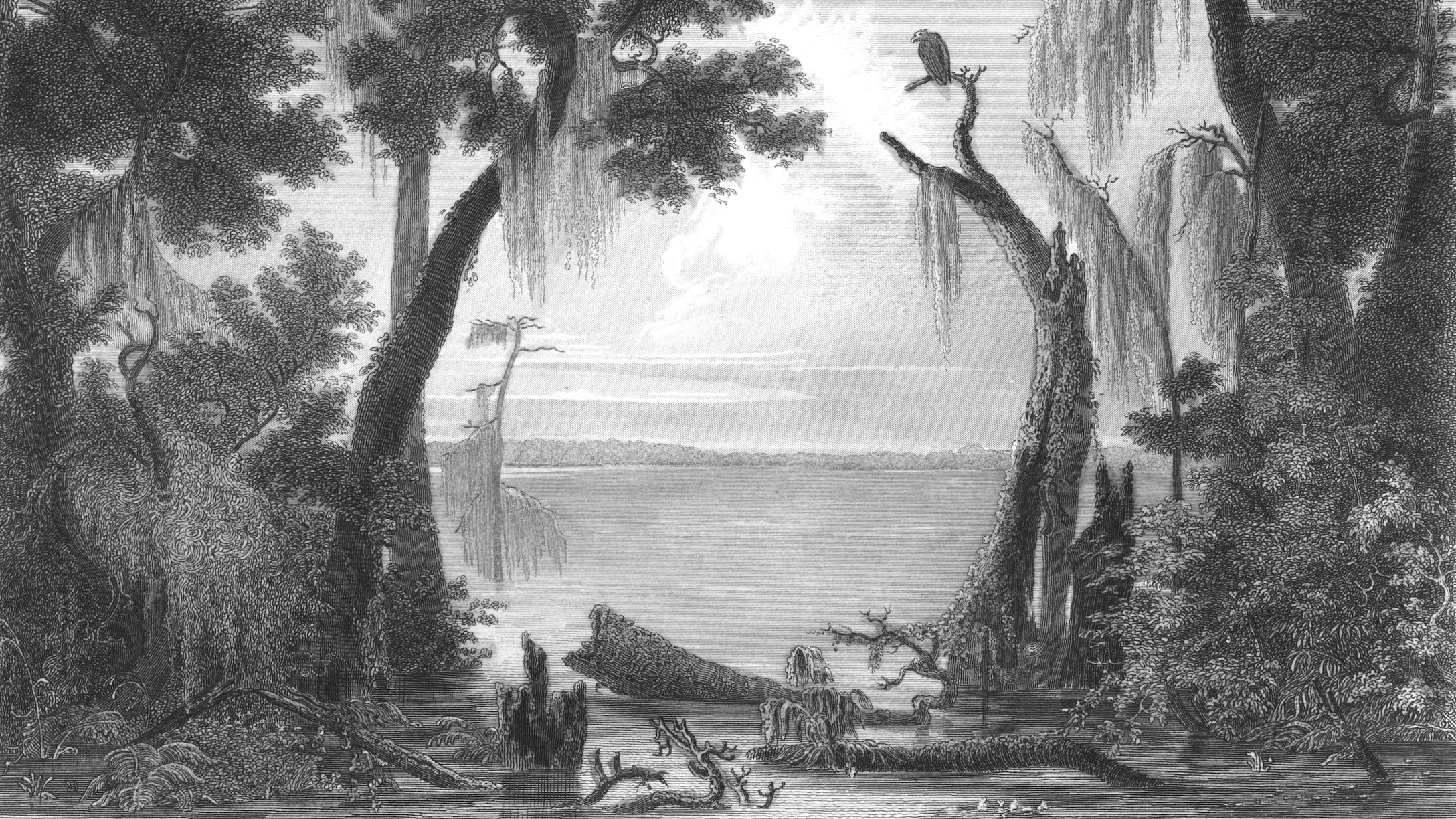

For early colonizers, swamps posed a problem of category: neither land, which people thought of as private, nor water, considered public. Their ambiguity made them suspect. They were, moreover, dark and smelly, unnavigable, pestilent, deceptive — any step could be a sinkhole, sheltering alligators and cottonmouths. Swamps were physically low places, the opposite of how white Americans wanted to see their land: as a shining city on a hill. European colonists “projected a moral landscape onto the physical landscape of the New World,” writes Ann Vileisis in her authoritative history, Discovering the Unknown Landscape: A History of America’s Wetlands. They didn’t even have a word for what they were looking at, and the boundaries of what they settled on stayed fluid; swamp can cover a lot of terrain, from tidal marshes to cranberry bogs. The definition Americans returned to most often was the capitalist one: they thought of swamps as land that simply had yet to be turned into land through drainage. The swamp was defined by what it wasn’t, or wasn’t yet, and by its resistance to being made useful.

The swamp’s reputation was shaped further by the people associated with it — at first, indigenous Americans. Native tribes hunted and fished in the North American wetlands, and retreated there to escape Europeans; the colonists took this as “a sign that the landscape itself was evil,” Vileisis writes. Puritan minister Roger Williams thought “the Indians did not fear the colonists because they anticipated assistance from Satan when they fled into swamps.” In 1770, William Bull, the lieutenant governor of South Carolina, said that without drainage, southern swamps were “otherwise useless and affording inaccessible shelter for deserting slaves and wild beasts.”

For enslaved people seeking their freedom, the beautifully named swamps of the south were places slave catchers couldn’t navigate — the Congaree in South Carolina, or the Okefenokee of Georgia, which later provided shelter for Confederate deserters as well. Native Americans fought back against white armies from within their wetland redoubts in Florida and elsewhere. In Louisiana, the Atchafalaya basin offered a place for new immigrants like Acadians to live unmolested, getting by on catfish and muskrat.

Swamps provided relief, in short, to successive waves of refugees from the racist American experiment. And it’s here that Donald Trump — however accidentally — has stumbled onto an apt metaphor for the project of Make America Great Again. Think of wetlands as unproductive, vaguely un-Christian, fundamentally unreadable to white racists, and hospitable to communities the U.S. has abused. Think of reclaiming wetlands as economically short-sighted and environmentally ruinous, an act that, throughout history, has robbed marginalized populations of the spaces that support them. Of course Trump wants to drain the swamp.

The first president to try it was George Washington. Prior to holding office, Washington was involved in a project to drain the Great Dismal Swamp, which straddles the border of Virginia and North Carolina, and turn it to farmland — the kind of work going on up and down the eastern seaboard, where white land- and slaveholders like Washington forced enslaved people to redeem wetlands by converting them to farms and plantations. The Great Dismal project failed. But Washington’s endeavor did reveal another source of profit to be found in swamps: wood. The venture became a timbering operation, and soon the idea that swamps were pristine sources of virgin wood took hold broadly. In 1850, Congress passed the Swamp Land Act, which gave possession of federally owned wetlands to states that would drain and develop them. Politicians debating the legislation expressed the prevailing attitudes, referring to swamps as “prolific of disease” and “generative of noxious influences.” A Louisiana senator, quoted by Vileisis, argued that swamp drainage would nationally result in the “increase of population, the augmentation of wealth, the cultivation of virtue, and the diffusion of happiness.”

While enslaved people toiled around the edges of the Great Dismal Swamp, its deep interior featured a different scene. Those who had escaped slavery set up camp, living for generations in communities of residents who came to be called maroons. Collectively and individually, people fleeing slavery hid out in swamps throughout the south. In Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Harriet Jacobs described taking refuge in a snake-infested swamp near the plantation she was fleeing: “Even those large, venomous snakes were less dreadful to my imagination than the white men in that community called civilized.”

Still, the most famous maroons were those in the Great Dismal Swamp. In Slavery’s Exiles: The Story of the American Maroons, historian Sylviane A. Diouf tracks Great Dismal communities so well established that accounts exist of families who lived their whole lives in the swamp’s protection — their children never seeing a white face. A lore gathered about the region, even outside it. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem “The Slave in the Dismal Swamp,” for instance, begins: “In dark fens of the Dismal Swamp / The hunted Negro lay.” In 1851, the northern abolitionist Edmund Jackson wrote that the Great Dismal’s residents had “established a city of refuge in the midst of Slavery.” Archaeologists are still uncovering artifacts from the maroon communities that made their home there.

One Virginia businessman put the total economic losses represented by those escapees at $1.5 million, though economic losses weren’t the only thing white people feared: Diouf writes about a Great Dismal maroon named Davy, who “had killed a white man with a hatchet over a disputed fish and buried the body in a pond under the mud. Following his father’s advice, the young man disappeared into the swamp and remained under cover until 1865. He went into hiding before 1817 and lived in the swamp for at least forty-nine years.”

Communities of maroons represented not just a loss of property to slaveholders but a loss of the control over black people their society was built on. They stood in for the threat of black organized power — particularly after it was learned that Nat Turner planned to hide out in the Great Dismal Swamp following his frustrated revolt. “Antebellum southern newspaper stories,” writes historian Tynes Cowan, “are punctuated with horror at the prospect of growing communities of Negroes within the swamp.”

The space existed, argues Anthony Wilson in Shadow and Shelter: The Swamp in Southern Culture, at the ideological edges of white southern society:

The swamp threatened the crucial order of the plantation system, sowing discontent among the enslaved through the example of those who lived outside the system they were compelled to perpetuate with their labor and providing limited prosperity to those excluded by the Southern order.

Swamps sat outside the territory of the dominant culture, places where communities who didn’t seek to overturn the natural order could live off it for generations. This was the swamp’s promise and its threat, as white people treated their impenetrability as an affront: wild spaces they simply couldn’t control.

American technology caught up with American ambition in the 20th century, and wetlands were lost at a ferocious rate. “Once developers discovered the wealth to be had,” Wilson writes, “they moved to reap it with remarkable speed, creating a dizzying flurry of logging activity that transformed the economies of wetland areas, swelled their populations with stunning speed, then left a wasteland in its wake as the ‘inexhaustible’ timber supply was, by the mid-1920s, all but exhausted.” As swamps disappeared, their reputation in the American imagination was somewhat redeemed — including by Harlem Renaissance writers like Jean Toomer and Zora Neale Hurston. Black artists, Wilson writes, “found and expressed a profound sense of cultural history, divinity, and even a kind of purity in the swamps that had sheltered escaped slaves and served as daunting but liberating natural churches for the remnants of African religion.”

William Faulkner, too, recognized the landscape’s importance, symbolically and ecologically. Thomas Sutpen, the poisonous Confederate progenitor at the center of Absalom, Absalom!, raises his hundred-square-mile estate from virgin Mississippi swampland, forcing a French architect and a team of enslaved African people into the lethal, pestilent work of construction. They “drag house and formal gardens violently out of the soundless Nothing and clap them down like cards upon a table,” Faulkner wrote, “creating the Sutpen’s Hundred, the Be Sutpen’s Hundred like the oldentime Be Light.” There’s a mythic and elemental quality to the creation of Sutpen’s estate, a sense of something from nothing. It’s the same kind of mythmaking white Americans constructed — a country created where nothing previously was — and in its particulars the raising of the Sutpen estate recalls the planning of the capital of American empire, Washington, D.C., another immaculate tract designed by a Frenchman and built with slave labor on wet terrain.

In another Faulkner work, “The Bear” — set after the war — the protagonist watches as the Mississippi bottomlands are timbered and hauled away, nothing left but useless cutover. In real life, such activity eventually increased flooding along the Mississippi River, while bird populations everywhere, nurtured by wetlands, declined, inspiring the first federal wetlands-protection legislation in 1928. In the 1950s, reflecting an emerging ecological consciousness, the U.S. government stopped calling them “swamps” — hoping to shed centuries of baggage accumulated around the word — and started calling them “wetlands.” Another good old American maneuver: the rebranding.

Still, some of the old ambivalence remains. Neither land nor water, swamps present an obvious problem for American ideals of ownership. Like rivers, they require a kind of public-spiritedness: I can’t dam my section of the river without causing problems for my neighbors up- and downstream, and so the water’s very presence — in theory, anyway — encourages empathy and fellow-feeling. Likewise, I can’t drain the bit of swamp abutting my property without mucking it up for everyone else.

The benefits of wetlands are also collective. Intact hydrological systems help all — wetlands, for instance, store carbon, and support fish and bird habitats — whereas drainage enriches the drainer. As a 1994 article in American Heritage put it, “As harmful as drainage can be, it remains very attractive for wetland owners, for it can leave a net profit, while many of the costs — increased flood heights, dirtier water, impoverished wildlife, disfigured scenery — are passed on to others.”

There is a persistent historical relationship between wetlands reclamation and authoritarian governments. Benito Mussolini’s government undertook a massive project to drain Italy’s Pontine Marshes, framed as an assault against malaria and the opportunity to develop a pristine, fascist version of nature — as opposed to the real, uncontrollable kind, which the fascists saw as a kind of internal enemy. In Iraq, to root out Shiite forces hiding within, Saddam Hussein drained the ancient marshes at the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, thought of as the site of the Garden of Eden. (Undergoing restoration, the area is now Iraq’s first national park.) American swamp drainers have often used martial, in addition to moral, language to characterize what they see as the problem. In 1911, a government scientist described wetlands as akin to “a wondrously fertile country inhabited by a pestilent and marauding people who every year invaded our shores and killed and carried away thousands of our citizens.”

In his own way, Donald Trump is just reminding us what it means to drain the swamp, which as a literal activity has always been suffused with punishing racial and capitalist undertones. The language of invasion, plague, eradication — this is how Trump and his allies talk about their own internal enemies: immigrants, people of color, disabled people, queer people. (Trump has referred to alleged immigrant gang members as both “animals” and an “infestation.”) It’s here, finally, that “drain the swamp” becomes an apt expression of the politics of Make America Great Again, which similarly involves preying on the vulnerable, wiping away social and legal protections as if they were centuries-old Florida mangrove forests.

The environmental disaster that swamp drainage represents — long-term ruin for many in favor of short-term gain for a few — is part and parcel of this politics, and Trump is a threat to swamps in a literal sense as well. His administration has proposed the reversal of the Obama-era Waters of the United States rule, which extended the authority of the EPA and the Army Corps of Engineers over not just lakes and rivers but wetlands as well, in recognition of the interconnectedness of the watershed. In Trump’s America, everyone gets to drain and pave his part of the swamp, no matter the consequences for others downstream.

“Draining,” anyway, isn’t the preferred term of art. When we talk about seizing land or water for human use we refer to it as “reclamation,” a word that begs the question. Was the swamp ever really ours to begin with? Trump’s ascent has inaugurated a new season of battle over the claiming and reclaiming of American history — if it properly belongs to those who have suffered its worst abuses or those who have got off easier, the swamp drainers, who insist it is their turn to make America great again. Trump doesn’t care about swamps qua swamps, but of course “drain the swamp” is the rubric he bumbled upon for his political program: he’s here to revive the worst parts of the country’s natural and political history, to reenergize its worst people. Trump and his supporters are motivated by a fantastical sense of historical racial grievance — a belief something has been taken from them that demands redress. Trumps wants to drain the swamp in the oldest American sense; his followers envision a country that exposes the vulnerable while the rapacious profit. They claim the birthright of America itself, a land of the white imagination where the unmolested swamp — diverse and ambiguous, rich with life, poor in capitalist value — is simply incomprehensible.