When the leaves fall, they open a clearing in the trees which allows me to see a hidden cemetery from the top of the steepest hill in my neighborhood. It’s as much an annual sign of the changing of the seasons as the autumn drop in temperature, and soon it will be time to see them again, these squat, moss-covered markers that designate the end of ten lives each, row upon row until my count passes two thousand.

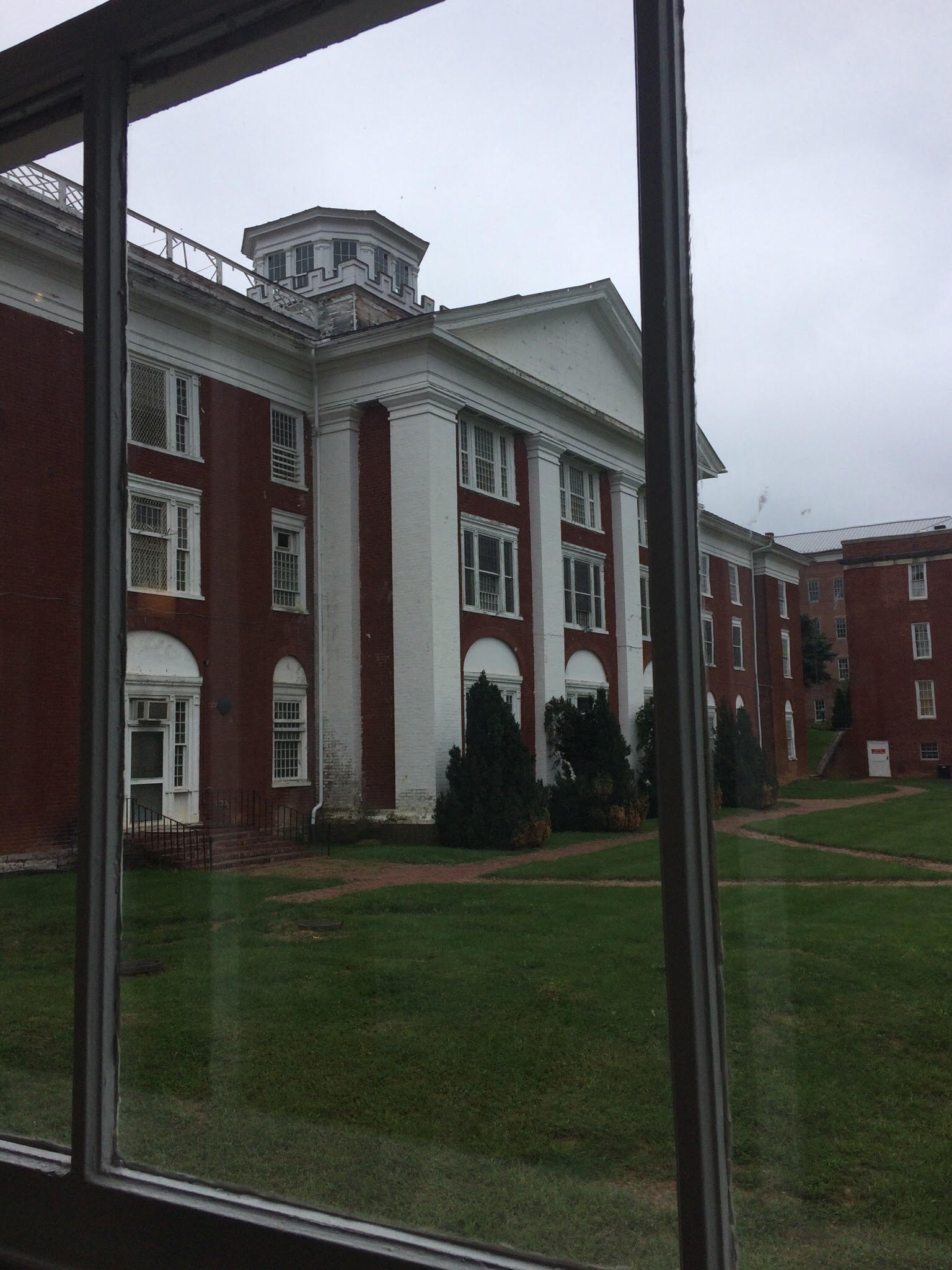

The men, women, and children buried in nameless rows had been confined to Virginia’s Western State Hospital, a psychiatric facility established here in Staunton, in 1828; these are the graves of those who died indigent or without family and rest in anonymity due to privacy laws. Today, the facility has been rehabilitated—in at least an architectural sense—as a high-end development: instead of housing patients suffering from dementia, epilepsy, mental health conditions, and addictions, the 80-acre, 18-building complex now features luxury condominiums—The Villages at Staunton—and a boutique hotel, The Blackburn Inn.

The cemetery is still there, however, and though it must remain, the graves are neglected; few legal protections compel their custodians to care for them, the same vulnerability that the patients endured in life. Some must have died at peace. But many others were the subjects of cruel experiments and non-consensual “medical” procedures; many were sterilized in a time when eugenics was the moral law of the land. A “no trespassing” sign warns potential visitors away from this cemetery, this place where broken markers jut up like stubborn reminders of things progress would prefer to bury and forget.

Though not a secret, the cemetery has fallen into a limbo since the city transferred ownership of site to private developers in 2006. A cemetery filled with the indigent burials of those once deemed insane will not facilitate the new urbanism that investors hope to bring to my quiet corner of the state, and the newcomers they hope to attract. While a few amenities are marketed to local townspeople, like the hotel’s restaurant—a sterile-feeling bistro that features “Virginia’s finest bites”—the hard-sell is reserved for tourists and for those in search of a second home or a retirement home; for them, Staunton is a place that’s not too far from children and grandchildren in the metro D.C. area.

What is a small, historically-minded community meant to do with something like Western State? These buildings were not only an asylum; when Western State Hospital completed construction of new facilities in the 1970s, the old site was transferred to the Virginia Department of Corrections and was used as a minimum-security prison from 1981 until 2002. Depressingly few updates were required. What is Staunton to do with a site that was a human warehouse mere decades ago? Today, the privilege of living there comes with a $400,000 price tag.

The United States offers no shortage of landscapes with “troubled” histories, from former plantations to penitentiaries. But if it would be a waste to destroy them all, we can hardly make them all into museums. And so, somewhere in between is what planners, investors, historians, and architects call adaptive reuse: giving a new purpose to an old building while preserving something of its history or character. Historic preservation was once driven by a quest for permanence—think of stodgy old house museums, frozen in time—but it is now, also, a tool of economic development. Adaptive reuse is also, simply, real estate development.

Yet while it’s one thing to put a post office in an old bank, it’s quite another to host wine-tastings in an asylum, a prison, a graveyard. And so, at Western State, the developers emphasize the architectural pedigree of key structures, laying a forceful claim to the site’s very earliest history, an optimistic time for psychiatric medicine when the cemetery was less crowded. Physicians believed that idyllic surroundings could soothe troubled minds, and the mountains of Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley offered natural beauty that complimented a philosophy of architectural design.

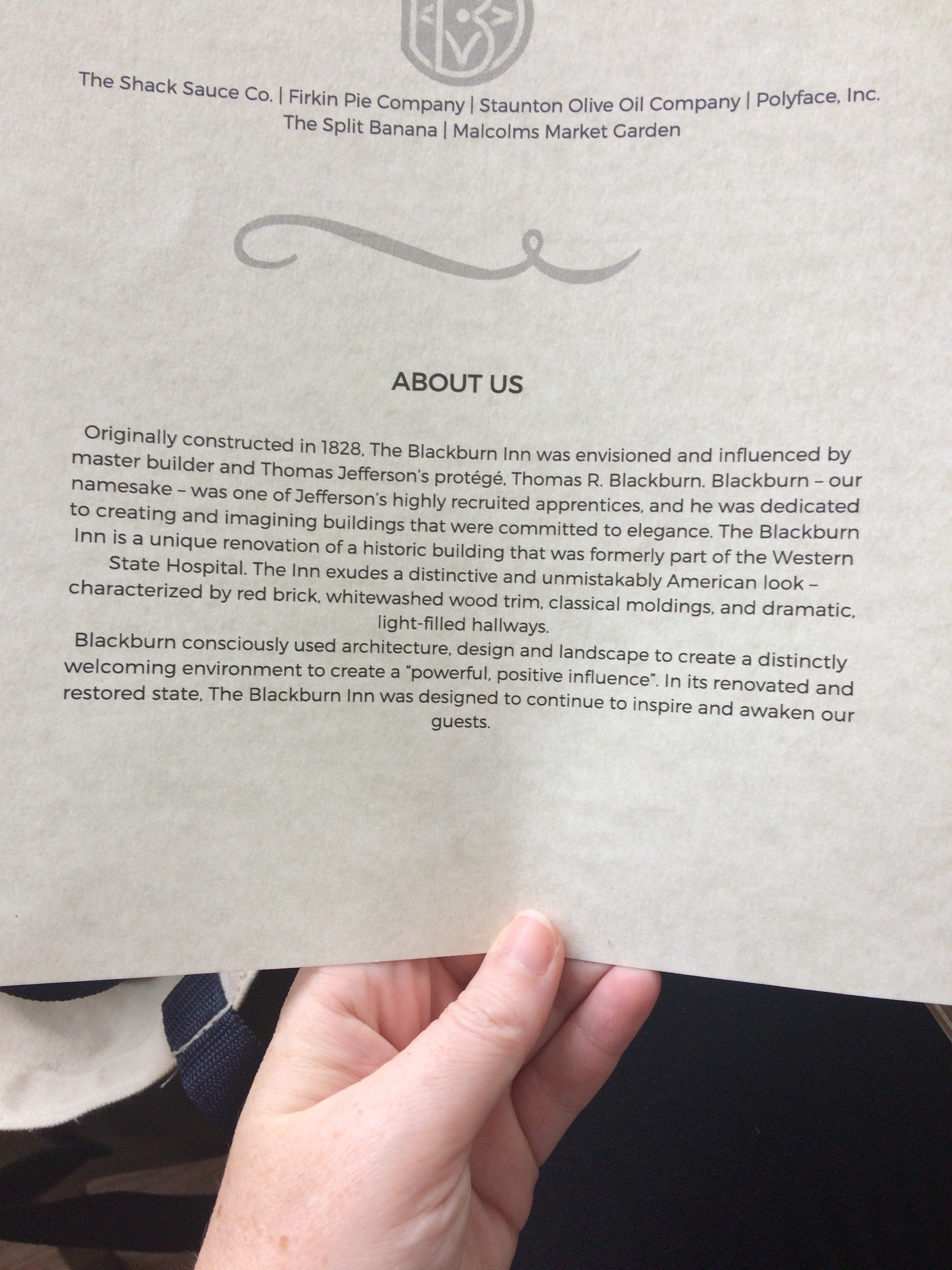

The Blackburn Inn, for example, is named after architect Thomas Blackburn, a protégée of Thomas Jefferson, who in the early 19th century worked closely with superintendent Dr. Francis Stribling to design a hospital core that patients would find comforting and pleasant. According to architectural historian Bryan Green, Western State is “the only known collaboration of physician and architect to construct and implement such a marriage of treatment technique and physical setting.” Their partnership of Blackburn and Stribling occurred during a moral period in what we now call “psychiatric medicine”: because Stribling believed a goal of treatment was to return patients to society, he regarded them while under care as friends and brothers.

“We treat them as human beings deserving of attention and care, rather than criminals and outlaws, meriting not even our compassion,” he wrote in the hospital’s 1837 annual report. Blackburn, learning from Jefferson, believed that the design of buildings could change human behavior for the better. One of the developer’s favorite anecdotes about the site is from Stribling period: “The hospital was built in a pastoral setting to help the healing process for the mentally troubled,” he told the Richmond Times-Dispatch. “The site was so beautiful that a fence surrounding the property was not meant to keep residents in, but to keep townspeople from going on picnics on the campus, or so the legend goes.”

This legend happens to be true; as a historian, I will do them a solid and confirm that Stribling took out a notice to the public in 1848 warning off recreation-seeking on the grounds. By 1853, construction had begun on an iron fence around the campus. It’s a historical detail that easily collapses past and present. The site is beautifully restored, including the fence. But, with the average per-capita income for Staunton at $19,000 and property prices set to lure affluent investors, a fence is no longer needed to keep most locals at bay.

Of course, having a moral period also means there was an immoral period: the fences and warnings (and eventually guards) weren’t always directed outward. In the twentieth century, Western State’s reigning philosophy was eugenics; Dr. Joseph Dejarnette was Western State superintendent for forty years, until 1945, and he was an eager practitioner of eugenic sterilization, as well as other treatments now judged inhumane: electroshock therapy, blood transfusions, and lobotomies. Virginia first legalized eugenic sterilization after the infamous Supreme Court case Buck v. Bell, and Western State would eventually sterilize over 1200 patients; Dejarnette himself performed half the operations and even set up his own private clinic just down the road to “treat” additional patients, many of them children.

Between 1924 and 1979, eugenicists in Virginia sterilized around eight thousand people. The only burden placed on physicians and courts was to demonstrate that a patient was symptomatic of hereditary forms of insanity or feeble-mindedness. But prevailing definitions captured a range of people undesirable to Virginia’s elite, from women considered promiscuous and childhood epileptics to people who were simply Black or poor. Historian Daniel Kevles, in In the Name of Eugenics, quotes a store owner from southwest Virginia, who describes what locals called “mountain sweeps” to round up poor families receiving government assistance.

“Everybody who was drawing welfare was scared they were going to have it done to them,” he remembered. “They really got them on Brush Mountain. The sheriff went up there and loaded all of them in a couple of cars and ran them down to Staunton to sterilize them.”

Dejarnette mocked, via poetry, those who found his methods cruel: “Defectives will breed defectives/insane will breed insane/Oh, why do you allow these people/to breed back to the monkey’s nest/to increase our country’s burdens/when we should only breed the best?”

I think of this poem when people say that Dejarnette was simply a man of his time, that his philosophies were unfortunate but universally accepted. If his deeds had no opposition, who is he mocking? If eugenics went without saying, why did he say it? Maybe the protests weren’t recorded in poems, or weren’t recorded at all, or were recorded but we’d prefer to forget, letting time take care of it. In 2015, Virginia’s legislature authorized a compensation program for the victims of eugenic sterilization, but as is so often the case, it came too late; by that time, the living survivors only numbered in the dozens.

Robert Kirkbride, a descendent of famed physician and asylum architect Thomas Story Kirkbride, told CityLab in a 2015 interview that “Buildings didn’t commit people. People committed people. But it’s easier to blame buildings than human behavior.”

This is accurate. But buildings are also assets, and their value gets determined, in part, by the residue of the human actions that took place within them. It isn’t just lead paint and asbestos that a building like this has to reckon with; it’s the cruel history it can represent. And yet people don’t really seem to “blame buildings,” as far as I can tell. The opposite: architecture is the thing that redeems them. As they are sanitized, loss in the past becomes gain the developer, in the present, speculating on the future.

If you go online to read about The Villages at Staunton or The Blackburn Inn, you’ll find the same clean and uncluttered web-design in both; crisp text against blank backgrounds. Until recently, a quote from English writer Virginia Woolf advertised the inn’s restaurant: “One cannot think well, love well, sleep well, if one has not dined well.” That advertisement disappeared. Perhaps someone pointed out the oddness of it? That putting stuffed mushrooms side-by-side with a woman who endured barbaric treatments for her depression—tooth extractions and force-feedings—and eventually took her life, perhaps, was a little bit off?

Now that I type that out, though, it doesn’t seem odd at all.

Not long ago, my partner and I had lunch at the site. We ate slightly over-priced sandwiches made with locally-sourced ingredients and we talked about the dead.

We talked about Cinderilla Dobbs, for example: she was the daughter of a cooper, admitted to Western State in 1857 when she was twenty years old. According to the admission register, she had been “disappointed in love.” She died after seven years of confinement and is buried in the neglected cemetery, perhaps finding peace near Cupid Allen. As we ate, staff deconstructed a sailcloth tent that placed on the lawn for an out-of-town wedding party.

We went as historians to see if we could accept the site for what it is now, not fixate on what it used to be. Could we remember the dead while also embracing a new chapter for their place of confinement? We wanted to give it a chance. Yes, it projects a cherry-picked history, but we’ve been in many museums that do the same, and just as arrogantly.

Strolling the grounds, afterwards, I realized that what made me uneasy about the site’s development wasn’t the fantasy it tells about the past, about famous architects and moral medicine. It was the fantasy it tells affluent people about the present.

Architecture matters. Buildings reflect who we think we are, and who we want to be; in this redevelopment, we’re invited to imagine ourselves as people who treat the most vulnerable among us with care and tenderness. To those who cannot be repaired we would give ethereal, pastoral beauty; what God could not provide through the bounty of nature, we would give, in the spirit of brotherhood for our fellow man. In this way, in this place, we stake a claim to the legacy of those who eased suffering; we claim we are people glad to marshal our wealth in compassionate acts.

As a community, we find it distasteful to admit that buildings designed by a great architect were built by those who were enslaved and, later, confined. This practice still continues. Virginia law mandates the use of prison labor to supply furniture and goods to Commonwealth institutions, like public universities. Virginia Correctional Enterprises, which manages the state’s prison labor program, boasts that its work benefits those incarcerated, by providing them with valuable skills. What are prisons but modern-day asylums?

We are still people who confine children and subject them to inhumane corrections, not just in some far-off ICE detention center but in our own backyard. And we are still a state that executes individuals with mental illness. We live in a country that makes access to mental health treatment so difficult that even a Virginia state senator’s son was denied emergency care, and took his life a day later. Many of our local elected leaders still fight to keep affordable healthcare beyond the reach of the poor, perhaps supported by those tempted to the region by the lure of second homes. Some would call this eugenics by a different name.

We believe we would have been Dr. Striblings, not Dr. Dejarnettes. But here in the present, we have that choice, right now, and we have made it. We are not even people who can take care of a cemetery.