Three times a week my father, a Sunday School teacher and deacon, took the family to a local Fundamentalist Baptist church. It belonged to the General Association of Regular Baptist Churches, but the acronym GARBC was used by some of the less devout for the Grand Army of Rebellious Baptist churches. There I encountered the book that shaped my language, and my childhood; the book that I cannot escape, written by a committee four centuries ago. This is the “Authorized” or King James Version (KJV) of the Bible in English. Eventually there would come a time when I realized that the book which said “let there be light” was also full of dark words. I have yet to forgive this book for the sins of so many of its readers.

But as a kid I had my own KJV and I soon became a whiz at Bible sword drills. In Sunday school the teacher would call out a verse and we kids would thumb through our Bibles, “the Sword of the Lord,” to find it first. Memorizing the order of the books, old and new, was necessary. And there was no cheating allowed, not those fancy Bibles that had a little thumbed indentation along the margin with the name at the start of each book. The idea is that all the youths in the class would hold their Bibles up in the air as a chapter and verse was called out, like Hezekiah 3:7. The pros, like me, knew there is no book of Hezekiah in the Bible, so we snickered at the babes. Whoever found the verse first jumps up and reads it. I had fast hands, so I often won. I remember one time winning a toy pistol as a prize.

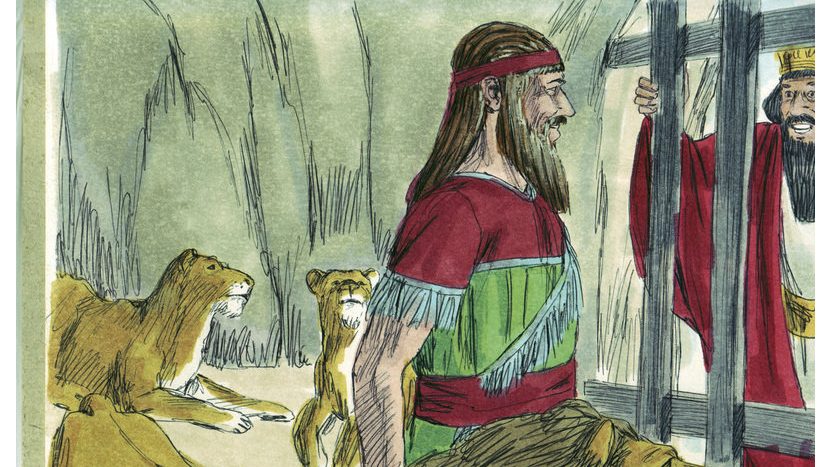

I still get chills and at times thrills from reading the litany of thees, thous, wist nots and verilies. Being named for the biblical prophet Daniel, his chapter became one of my favorites. Little did I know at the time that the text I was reading in the late 1950s had been revised into a more modern idiom. I am not sure how my elementary school learning would have tackled an original 1611 verse like Daniel 1:8: “But Daniel purposed in his heart, that he would not defile himselfe with the portion of the kings meat, nor with the wine which he dranke: therefore hee requested of the Prince of the Eunuches, that hee might not defile himselfe.”

Bible trivia was my Game of Thrones. I collected all kinds of questions about the Bible and its characters. For example, what is the shortest verse in the Bible, but definitely not a good choice for sword drills? The answer is John 11:35, which only has two words: “Jesus wept.” In hindsight, this may be one of the most profound statements in Holy Writ. Some were trick questions: How many people did Jesus feed with two loaves of bread and five fish? Those who really knew their Bible also were aware that it was five loaves and two fish, the answer to that being about 5,000. There were also jokes, like who was the shortest man in the Bible? The answer could be Nehemiah (knee-high-miah) or better yet, Bildad the Shuhite (shoe-height), a friend of poor old Job on his dunghill.

To grow up in a small Baptist church is to sing a lot of hymns. I imagine that I have sung over a hundred different gospel songs in my youth and many of the choruses and melodies still stick in my mind. The hymn book I remember best had all the old KJV-inspired standards from “The Old Rugged Cross” and “Bringing in the Sheathes” to “Standing on the Promises” and “There’s Power in the Blood.” Bible Baptists are not faint about songs of blood. Saturday night was my weekly bath and Sunday I would be “washed in the blood of the Lamb.” But the young kids start out with an easy chorus:

“The B-I-B-L-E,

Yes, that’s the book for me.

I stand alone on the Word of God

the B-I-B-L-E.”

The Bible, of course, was the KJV—the one that kept in all those references to the blood. Given all that talk about blood, I wondered what that grape juice we drank during communion really turned into.

When did I stop believing or thinking I believe? Up until my second year at an Evangelical college I continued to go to a church every Sunday, although the more I read philosophy, the less sense any of what I heard in sermons meant to me. Coming from a ritual barren Protestant background, I embraced the Christian mystics, finding a soulmate in Teilhard de Chardin, even if I could not pronounce his name. I wore a cross around my neck and let my hair grow. I took German so I could read Nietzsche in the original and contented myself with a major in Biblical Archaeology. After two years in college I woke up one morning and realized I did not have to go to church, nor believe what had been drummed into my head during my brief lifespan. It was a secular epiphany, being born again, but on my own terms.

I still love the KJV and find it inspiring, not for what it says but the way things are said. My favorite book these days is Job, the unlucky target of a power struggle between Jehovah and Satan. He had everything: “seuen thousand sheepe, and three thousand camels, and fiue hundred yoke of oxen, and fiue hundred shee asses, and a very great houshold.” I much prefer shee asses to donkeys. But Job lost everything and was tormented by fair-weather friends who insisted he must be a great sinner. Even Bildad the Shuhite weighed in: “Behold, God will not cast away a perfect man, neither will hee helpe the euill doers.” I admire Job’s resilience, but he still was a castaway in a one-sided theological squabble. In the real world evil doers get all the help they need.

The real world is not what the original King James English is about. What made sense to the child in me no longer makes sense to the child I remain. The God I once thought created me came down considerably the more I read and re-read the KJV, as I realized how much the likes of him was created by the likes of me.

Daniel Varisco