In the summer of 1995, the Cleveland-based hip-hop quartet Bone Thugs-N-Harmony put out their first full-length album, E. 1999 Eternal. That August, I got a copy for my 10th birthday. The group had made a name for themselves just a year earlier, when their debut EP, Creepin’ On Ah Come Up, garnered some mainstream success, spawning hit singles like “Thuggish Ruggish Bone” and “Foe tha Love of $.” These were already staples of the homemade mixtapes my friends and I made. We waited patiently every Monday night with a blank cassette in our tape decks and our fingers resting eagerly on the record button. When our local hip-hop DJs, 8ball and the Chicken Man, cued up a favorite, we’d capture it for posterity.

Both records were produced by hip-hop mogul Eric “Eazy-E” Wright of N.W.A., the controversial L.A.-based, hip-hop group that had some years earlier drawn the ire of the Federal Government with the not-so-subtly titled song “Fuck The Police.” Creepin’ On Ah Come Up was a short but intense exploration of the gritty realities of growing up on the streets of Cleveland. But there was something about it that was new to hip-hop: a distinct spiritual undertone.

The album begins with a track called “Mr. Ouija,” which depicts the brothers Bone consulting the wisdom of the mysterious title character—presumably the personification of the notorious Ouija board. They ask him if they should expect to meet the same fates that have befallen young black men from their streets before.

Dear Mr. Ouija

I want to know my future.

Will I die of murder?

Of bloody, bloody murder

Come, come again…

By the time E. 1999 Eternal dropped, Eazy-E had already passed, the apparent result of complications from a particularly aggressive case of HIV/AIDS infection. His rapid deterioration made his demise into tantalizing material for conspiracy mongers. One prominent theory suggests that Wright was the first in a series of three high profile murders committed by the infamous Marion “Suge” Knight, the head of legendary west coast hip-hop label Death Row Records. He would also be implicated by the end of the decade in the deaths of Tupac Shakur and The Notorious B.I.G.

Others thought there had to be more malevolent forces at work in Wright’s death. This idea was exacerbated by his protégés’ preoccupation with the Ouija board and occult imagery; bad juju brought on by the Cleveland rappers’ experimentations with Satan’s preferred board game.

By the time I heard the album, I had already developed a sort of perverse fascination with the Ouija and spiritualism in general. My family’s friend and neighbor growing up, Mrs. Gail, was a bona fide practitioner of the dark arts—tarot, Ouija, palm reading, you name it.

Gail didn’t just do witchy stuff, she looked the part. She kind of reminded me of Stevie Nicks. This gave her more credibility as far as I was concerned, but it made my mom nervous. As a recent convert to Pentecostalism, she was concerned that Gail’s interest in the esoteric would leave her, and by extension, us, vulnerable to demonic possession. I wasn’t afraid of being possessed, but Gail did freak me out, with stories of Satanic rituals that had taken place in the small Appalachian mountain town I grew up in.

One such tale dealt with a band of witches that had come up from North Carolina to conduct a so-called “black mass.” Gail included all the important details, like how the participants hung naked baby dolls up in the trees of Lilley Cornett Woods, chanting spells and covering themselves in gasoline, before committing ritual suicide in sacrifice to Satan by burning themselves alive. For those who have never spent a day at the foot of the cross, phrases like “black mass” and “ritual suicide” may seem like the stuff of Hollywood. But they’re enough to make a young kid steeped in Christian baggage sleep with his lights on every night.

And yet, terrified as I was of the occult, I was drawn to it. Upon Gail’s suggestion, I went to the school library and checked out (and by “checked out” I mean stole—I could never be seen holding the devil’s work) Daniel Cohen’s book Curses, Hexes, and Spells. This little volume had frequently landed on various banned books lists in the United States, and to my knowledge, remains the only children’s how-to guide to witchcraft.

I was both repelled and fascinated by its depiction of Baphomet, the image of a man with a goat’s head, first drawn by 19th century French magician and occultist Elias Levi. It had been used earlier in the 14th century as damning evidence in the idolatry case against the much maligned Knights Templar. Today, the Baphomet is ubiquitous in hip-hop culture; several can be seen on the cover of Jay-Z and Kanye West’s Watch the Throne.

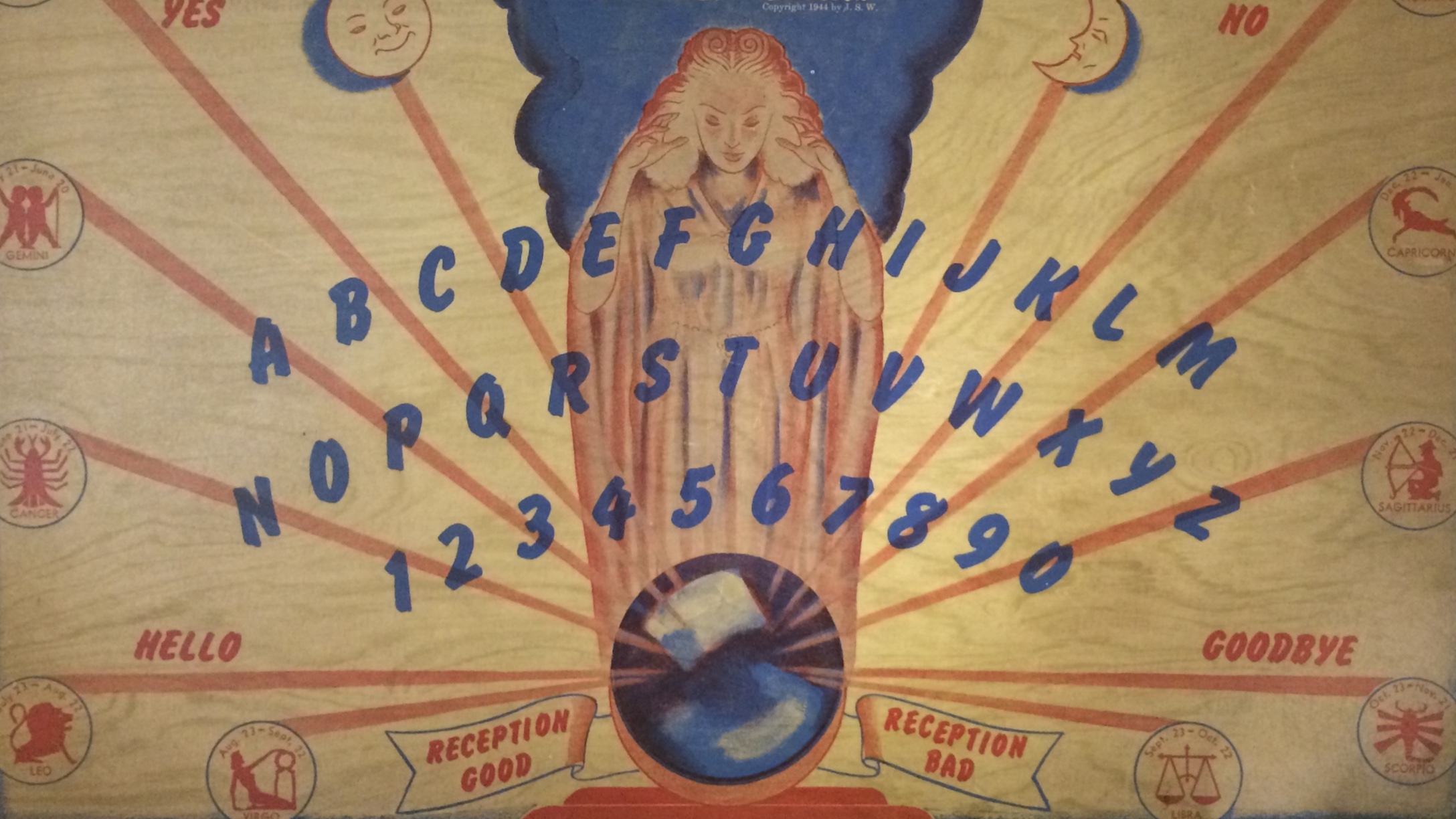

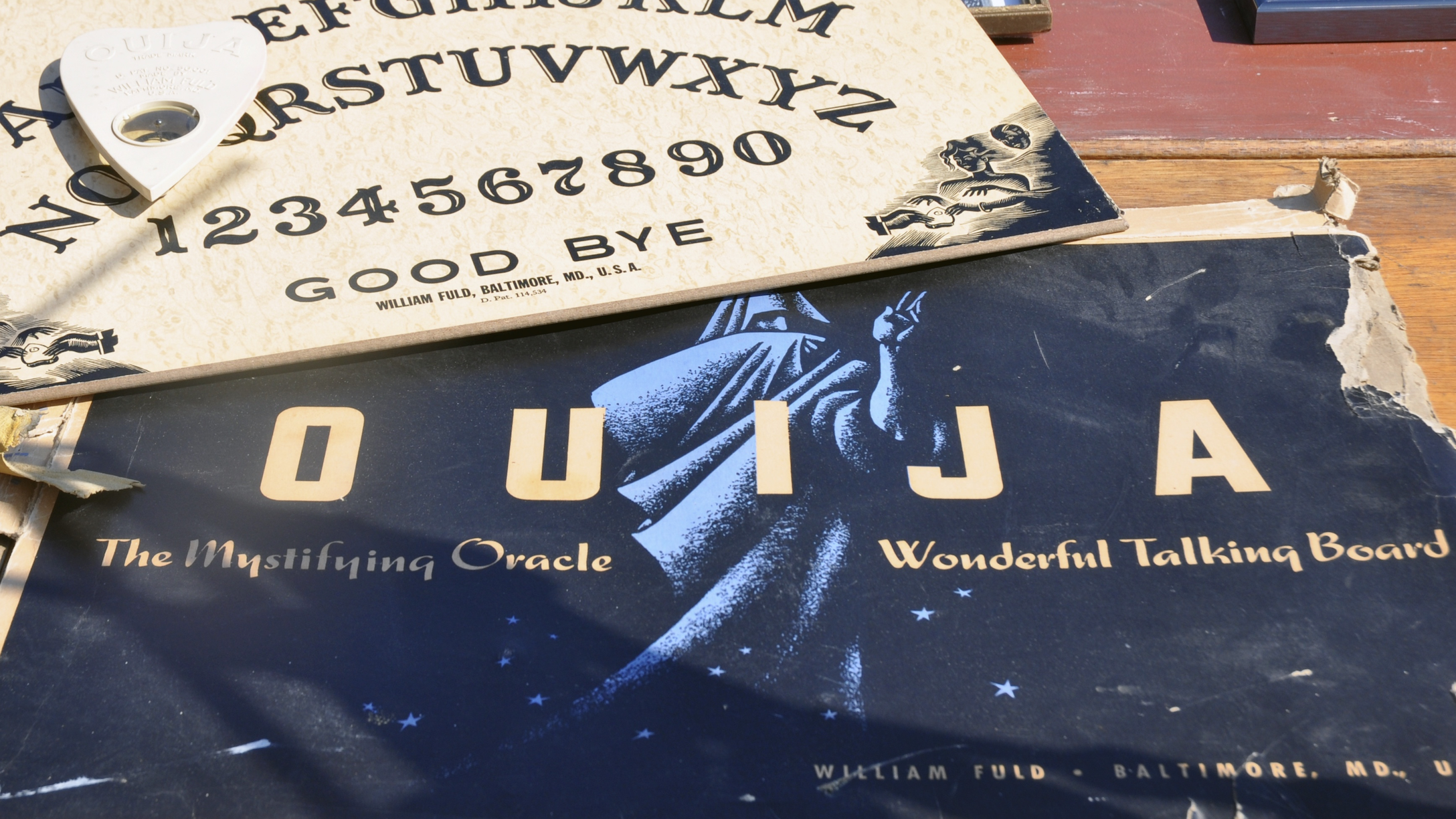

William Peter Blatty’s 1973 horror classic The Exorcist has cast a long shadow over public perceptions of the Ouija board. The story depicts a middle-class Catholic girl’s ordeal of possession by a malevolent spirit, after a seemingly harmless Ouija session. But before The Exorcist made it into a national sensation, the average American household held a considerably more benign opinion about the game. As Mitch Horowitz recounts in his book Occult America, the Ouija debuted in the winter of 1891, at the now defunct Pittsburgh-based novelty store Danzinger & Sons, at the cost of $1.50.

This “Wonderful Talking Board,” as it was first billed, differed little from “The Mysterious, Mystifying Game” sold by Parker Brothers today. It’s a flat board covered with letters, numbers, and the words “yes,” “no” and “goodbye.” The board is accompanied by a “planchette,” an arrowhead-shaped device, usually with a small, magnified glass window in the center. Two or more players (ages six and up!) sit around the board with their fingers on the planchette and ask it questions. The planchette moves from character to character and spells out answers, seemingly of its own volition. Whether this is due to black magic or the unconscious mind is for the player to decide.

By the time the Ouija appeared, spiritualists like New York’s Fox sisters and Madame Helena Blavatsky were already national pseudo-celebrities, conducting séances in the homes of influential people, most notably Thomas Edison. In the context of 19th century American Christianity, there was no spiritual conflict where the Ouija was concerned—spiritualism wasn’t yet seen as a contradiction in Christian doctrine. In an era where war, childbirth, and preventable diseases were claiming countless lives, it was a feat to make it into your late fifties. The idea of the living being able to commune with the dead helped many Americans come to terms with their own finite existences.

During the Great Depression, the Fuld company, which had started to distribute the Ouija Board nationally in 1898, opened new factories left and right to keep up with demand. The company’s founder, William Fuld, became a literal victim of his own success. In 1927, Fuld fell to his death from the third floor of one of his newly opened factories—a factory, he had eerily claimed, that the Ouija specifically urged him to build.

Even more bizarre Ouija stories started cropping up in national papers in the decades to follow, Horowitz reports. In 1930, two women in Buffalo, New York murdered another woman in their neighborhood claiming the Ouija instructed them to. In 1958, a Connecticut woman left a spirit she claimed to have contacted through her Ouija board $152,000 in her will; a judge eventually ruled against executing it. In The Smithsonian, Linda Rodriguez McRobbie points out that the Ouija—and spiritualism in general—tend to thrive during uncertain times. By 1967, as more troops were sent to Vietnam and race riots broke out across the country, Ouija sales outpaced Monopoly.

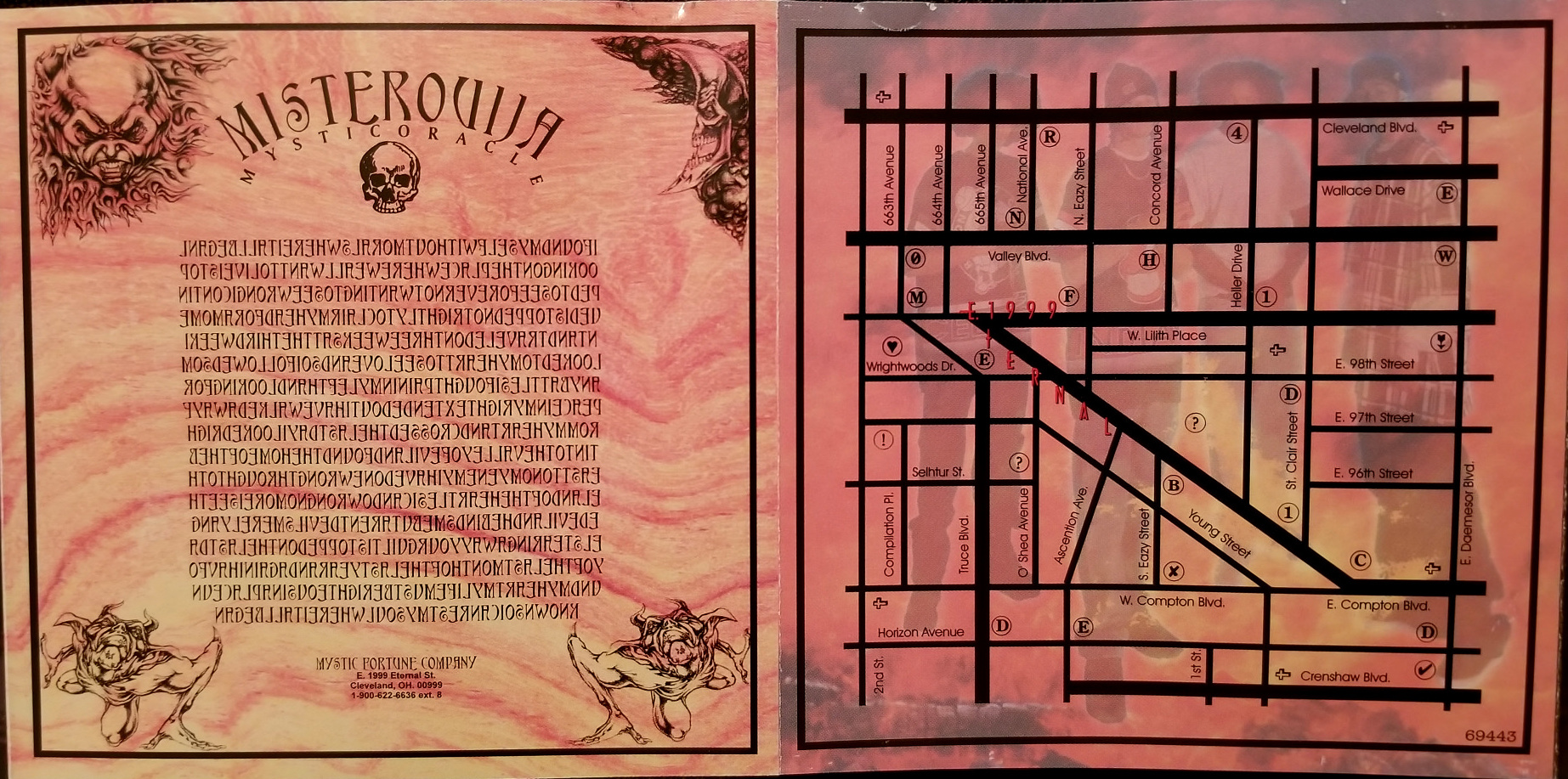

It only made sense, when I ripped the packaging off my copy of E. 1999 Eternal and took out the liner notes, to see a Ouija printed inside. The caption on the back of the sleeve read:

MISTEROUIJA

MYSTICORACLE

The following cryptic message went beneath it, written backwards:

I found myself without morals where it all began

Looking on the place where we all want to live I stopped

To see forever not wanting to see wrong I continued

I stopped not rightly to clear my head for a moment

And traveled on three weeks at the third week I

Looked to my heart to see love and so I followed so

Many battles I fought pain in my left hand looking for

Peace in my right extended out I have walked away from

My heart and crossed the last day I looked right

Into the valley of evil and found the home of the beast

To no my enemy I have done wrong through to the

Land of the heartless I can do wrong no more I see the

Devil and he binds me but aren’t devils merely angels

Tearing away your guilt I stopped on the last day

Of the last month of the last year again I have found

My heart my life must be righteous and a place unknown

So I can rest my soul where it all began

The concluding stanza was of a different form:

MYSTIC FORTUNE COMPANY

E. 1999 Eternal St.

Cleveland, OH. 00999

1-900-622-6636 ext. 8

Mrs. Gail had given me my formal introduction to alternative spirituality, so I consulted her as to what it all meant.

With a three-quarters smoked Camel full-flavored dangling from the corner of her lips, Gail took me into her bathroom, which smelled of her man’s Hai Karate and secondhand smoke. She held the liner notes up the mirror in order to read the backwards message properly. She began to squint, mumbling something under her breath. I stood by her side in a daze, eager to receive revelation. After a brief deliberation she turned to me and told me that the words were some kind of poem, and that whoever wrote them was probably a Satanist; she could tell by the “language.”

Thoroughly creeped but still fascinated, I became a Bone devotee. Listening to their music seemed even more dangerous and forbidden now than it had been previously, when the only element of risk was having to stow my CD in an old shoebox in my closet, along with other contraband of interest to preadolescent boys. Now I was gambling with my eternal destination! Conspiracies regarding the group’s allegiance with the devil were everywhere. One prevailing rumor of the day was that the Bone Thugs had sold their souls to the devil for the superhuman ability to rap incredibly fast. It was not unlike the legend of the Mississippi bluesman Robert Johnson, who was rumored to have done the same at the Devil’s Crossroads in Clarksdale in exchange for his singular mastery of the guitar.

The occult imagery in their album’s liner notes—not to mention their deceptively innocent hit “Tha Crossroads”—did nothing to quash this notion. In fact, such rumors of Bone’s affiliation with Beelzebub reached a fever pitch so fast—no doubt fueled by the Ouija’s dubious reputation—that it was believed in some circles that if you read the liner note passage, you were subjected to what was known as the “Bone Ouija Curse.” You, like the Cleveland rappers, would then be killed as tribute to Satan on January 1, 1999.

But January 1, 1999 came and went without calamity befalling me, or the Bone Thugs. For a boy raised in the Southern church, though, the possibility hadn’t seemed so outlandish. We spent our Sundays speaking in tongues and healing with the laying of hands, at the same time Satan was making a comeback in the American consciousness. Occultism was the subject of many a pre-internet-culture conspiracy, before there was a broad cross-section of people to validate your kookiness on Reddit. Most of them had their origins in Ladies Prayer Meetings. One of these was the urban legend that corporate giant Proctor & Gamble had donated a portion of their proceeds to the Church of Satan.

At the time, Proctor & Gamble was a major sponsor of daytime soap operas, one in particular being Days of our Lives. In the mid-90s, the writers introduced a controversial story arc where one of the female leads, Marlena, becomes possessed by the devil. Many of the same women attending those Ladies Prayer Meetings were also Days fanatics, and they arrived at the conclusion that the Cincinnati-based corporation must have some involvement with the Church of Satan.

Somehow this idea even trickled down to small-town Whitesburg, Kentucky—no easy feat at a time before internet was readily available. So my devout Pentecostal mother proceeded to do what any good Christian would do, which was to purge our home of all Proctor & Gamble products and boycott them at the grocery store. To this day, my aunt Brenda still checks the labels of her food and cleaning products to make sure they aren’t P&G. Can’t be too careful.

Coincidentally, Bone Thugs-N-Harmony put out a song around the same time called “Days of Our Livez,” turning the soap opera into a street opera. Depicting the threat of violence in the “wasteland” in which the song is set, it draws a connection between the earthly and the eschatological: “We gotta prepare / For eternal warfare.”

This past May, my mother retired, after having worked for more than 30 years as the City Clerk of my hometown. One afternoon, she called to tell me I’d been subpoenaed, over yet another unpaid private student loan I’d foolishly taken out as an 18-year-old and had been ducking ever since. Upon my arrival, I noticed a black Chrysler 300 in the driveway that wasn’t hers. When I made my way into the house, sitting at her kitchen table was a woman who I didn’t quite recognize fidgeting with some Camel cigarettes.

“Tom, you remember Gail, don’t you?”

Of course I did. We hadn’t heard much from Gail since those days. Sometime in the early aughts, my mom had gotten a mysterious delivery at the office. It was a landscape painting, a quaint Bob Ross-esqe cabin settled next to a river tucked in between some mountains. Gail had painted it for her.

Later I would find out that Gail had been through it. Her husband of many years had beaten her the better part of their marriage. Gail’s scarcity in the intervening years was probably a result of trying to escape that situation alive. If spiritualism sees renewed interest in troubling times, I now understood why Gail found solace in tarot readings and fortune telling. She had inherited a long tradition.

As Silvia Federici has written in her history Caliban and the Witch, witch hunts began as a means of domination over the lives of lower-class villagers, particularly women, in 16th-century Europe. The folklore and ritual practices that became understood as witchcraft were a threat to capitalism’s accumulation of natural resources, and their control by a privileged few. Federici writes, on the testimony of the accused at witch trials:

Their poverty stands out in the confessions. It was in times of need that the Devil appeared to them, to assure them that from now on they “should never want,” although the money he would give them on such occasions would soon turn to ashes, a detail perhaps related to the experience of superinflation common at the time. As for the diabolical crimes of the witches, they appear to us as nothing more than the class struggle played out at the village level: the “evil eye,” the curse of the beggar to whom an aim has been refused, the default on the payment of rent, the demand for public assistance.

This might also explain why many of us today, disproportionately women, trans, and nonbinary people, have found an aspirational figure in the archetype of the Witch. After Bret Kavanaugh’s confirmation as Supreme Court Justice, in spite of multiple credible allegations of sexual assault, groups convened to curse him. The figure of the Witch, even at a symbolic level, provides an identity for women and others preferable to the one this country is willing to offer them at the moment.

If this history seems a world apart from gangsta rap, the two converge in Bone Thugs-N-Harmony. Hip-hop, even prior to its expression through Bone’s esoteric lens, has always included spiritual examination, as a means of coming to terms with the plight of black youth in America. Before Bone, this was most apparent through the Islamic alphabetology of the Nation of Gods and Earths, often incorporated into the lyrics of rappers like Rakim, Nas, and the Wu-Tang Clan. What Bone brought back to the forefront was the dormant hybrid of Christian doctrine and occultism, unseen since the early 1900s, when middle-America integrated church-approved worship with more arcane spiritual practices. The occult aesthetics of Bone’s album art and music videos meshed seamlessly with Christian theology.

On the day of Gail’s visit, all I wanted to do was reminisce about the Bone Thugs Ouija curse. But I realized it might be a bit much to jump into after having gone 20-some years without seeing her. Instead, I offered the requisite “How you been?” before taking my subpoena and heading to the lawyer’s office.

On my way out the door, I remember thinking that Gail didn’t really look a damn thing like Stevie Nicks. Maybe it was just her sartorial choices, largely unchanged since the days I knew her: the earth tones, the sheer summer scarf, the sandals, the witchy accoutrements that adorned her wrists and ears. Under all of that, she was an ordinary person. Witches always have been. But she was the one who had first shown me the path to eternity, at a Cleveland address, reflected on the surface of a bathroom mirror in Whitesburg, Kentucky.

Tom Sexton