September 24, 2018

New York, NY

In the afternoon, traffic had more than quadrupled the duration of every trip. President Trump was in town. It was my last night in New York City. President Buhari was in town too, among others — two presidents of my two often dysfunctional countries.

Policemen littered the road like ants around sprinkles of sugar. Otherwise legitimate left turns on major roads were forbidden, so taxis, Ubers, and private cars had turned to more innovative approaches. “I figured what I’ll do,” my Uber driver said, eventually, after many veiled suggestions that he would drop me “nearby my destination” so I could walk the rest of the journey with six travelling bags and a four-year-old son. “That’s not going to work,” I replied, equally as politely. “I’m sure you’ll find a way.”

He did, eventually.

The ambiance around the Redbury Hotel on 29 East 29th Street where I initially stayed had been calm and normal enough for a busy city. Morning walks to Lenwich at the corner of East 31st Street and Park Avenue South to get a sandwich with my son, and, on another day, to Dunkin Donuts nearby, were filled with expected New York rituals: fast-walking residents going to work, lost tourists confused by Google Maps and looking for the way to Koreatown, people crossing the road by foot while the light remained red, pedestrians with varying breeds, sizes, and temperaments of dogs and poodles, businessmen on the phone, roadside constructions, and tourists on double-decker buses.

A day earlier, my son and I walked around, first through Park Avenue South, looking for a Bank of America where I’d decided to open a new account. We found one, but then realized it was a Sunday and only ATM services were available. The security man looked at us with no interest as he feasted on his hamburger. It was not his business to inform touristy-looking father and child of capitalism’s weekly schedule.

Kọ́lá Túbọ̀sún

Kọ́lá Túbọ̀súnFrom the ground, the Empire State Building looked a lot less impressive than movies had made it. The first entrance on East 34th Street was open only to tenants. For a moment, I wondered whether to pity or envy those who get to work in a building this curious to visitors. In the lobby were very American displays of what made the building such an iconic structure: its location, its history, its shareholders, and other graphic displays of what the tourist was to expect. A ride to the 112th floor: $37. A ride further up to the radio station that housed the famous antenna: another $12 or so. “Get your tickets on the second floor.”

In America, the first floor of a building is ground floor, the first floor your feet touch. The second floor is what comes after that, after climbing the stairs. In Nigeria, the ground floor comes first, because it is on the ground. The first floor is the floor you reach by climbing the stairs. Tourists with a bi-cultural outlook seem to accept these differences without question.

At the “second floor,” the line had begun to mill around where tickets were bought, and I had a change of heart. I had not come here to see the Empire State. The view from on top the Willis Tower in Chicago, impressive as it was, didn’t feel so special in hindsight, and it’s unlikely that the Empire State gives me more than the view from any regular American skyscraper, or the Gateway Arch, for that matter. I could see it already: stretches of concrete, a river, iconic buildings shining in a distance, a photo booth to show friends that we’d been here, and a gift shop to buy shiny fridge magnets, t-shirts, and other New York kitsch. It was no surprise that, according to reports, the building brought in more from its tourist visitor dollars than from rent paid by tenants. Luckily, my son wasn’t as intent on it as I had expected. Maybe he shared the burden of the loads on my back and hands. “We can come back here when your mom is back,” I said, not intending it to be a lie. “Maybe tomorrow.”

A few seconds’ walk from the junction of Fifth Avenue and East 29th Street is the Church of the Transfiguration. It had no real fence, and the trees and empty wooden benches outside its doors welcomed our weary feet for a few quiet minutes.

***

The Redbury had sold out and, having forgotten to book an extra night, I had to find a new abode before checkout time at 11:00. Hell is trying to find a hotel room in New York on the day of the United Nations General Assembly. All hotels nearby greeted us with “Sorry we’re fully booked. Try the next block,” or other more polite variations. Online, the cost of rooms moved up steadily with each second, and I was convinced I would have to sleep on the street like the many bodies I saw, snuggled on a warm air vent outside a building.

On East 31st Street, I found an available room. It smelled of cigarette and had very little space to move around as soon as one got off the bed. Three people couldn’t stay here comfortably, but this was one last night, and it appeared to be the only available hotel in a town milling around with diplomats and their family members visiting New York on a state allowance. “I’ll take it,” I told the man downstairs after I returned there from checking the room. “I’m sorry,” he replied. “While you were upstairs checking out the room, someone online booked it. I’m sorry, but it’s no longer available.”

At Salisbury, I got an upgrade at check-in, with two queen-sized beds in one room, and an open living room in another. There was space not just to move around but to avoid company whenever needed. The office desk in the living room area fit my laptop snug, and for a moment, I contemplated coming back there for weeks to write a book, Maya Angelou style. For that, though, one would need a large grant.

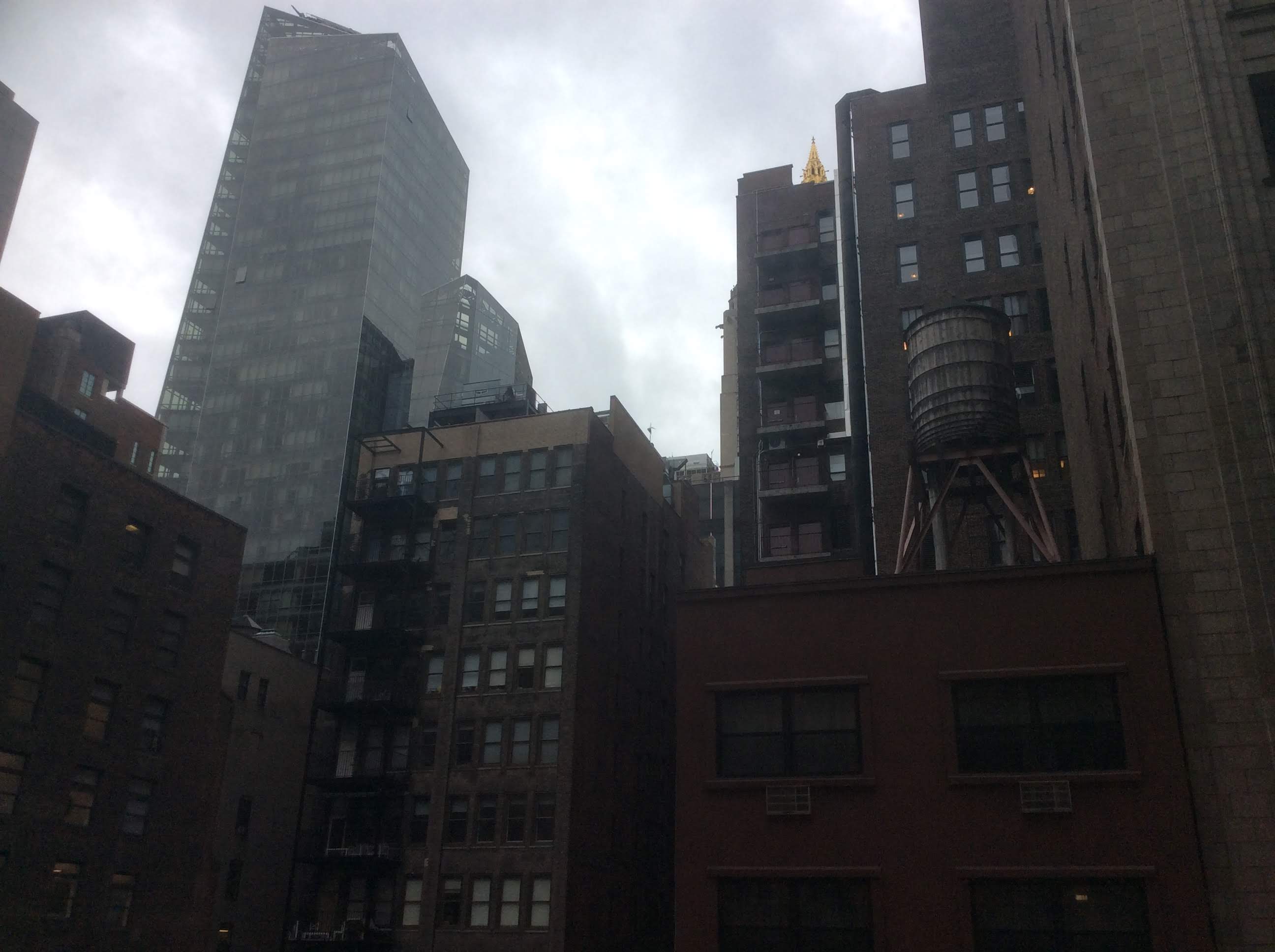

The view from the top floor was as expected — far less grand than it would have been from the Empire State Building, but nothing less typical: lights, passersby below walking from and towards each direction, condos across the road in other tall buildings some offering brief glimpses into what might lay behind the curtains. How much a desire for exhibitionism is behind the preference for glass structures in a big city, where lights often let in more eyes than one required?

Kọ́lá Túbọ̀sún

Kọ́lá Túbọ̀súnDownstairs, across the road, was a Starbucks. Beside it, a supermarket that the bellboy of the hotel kindly showed me as my son complained of his rumbling stomach. “You can get him a croissant there. And juice.” He was happy to hear it.

Before the supermarket, before the Starbucks, on the same side of the road, is a small bar called The Roof. When Ọláolúwa Òní and Túndé Wey came that night for drinks, we camped in there by the open window that gave a good view of the wet street, and drank into the night, until it was too late to stay up for she who wanted to wake up early for work the next morning, and he who had a flight to catch. But the bar hadn’t even signalled any intention of closing. (Túndé, a Nigerian-born chef, had come from New Orleans to attend an event in New York City, and Ọláolúwa, a Nigerian-born writer and reader, studied law at New York University, then decided to stay and work.)

It was either the cool comfort of the bar, a respite from the cold exterior of the alien town, or the heat from the Bourbon that Túndé requested from the bar, but the conversation, which ranged from Nigerian literature, entertainment, and politics, to American social and political environments and their impact on the world, flowed like sweet dreams with the music that seeped in through the walls.

Before then, Ọláolúwa and I had gone to have pizza at Angelo’s Coal Oven Pizzeria two doors away from the Salisbury. We noticed, during the meal, that we were the only black people there. The other guests gave my son nice pleasant looks as he traipsed up and down the aisle, happy for a free-range encounter. I couldn’t tell how much of the nice smiles from other guests was judgment for his restlessness or genuine mirth at our ordinariness, our comfort within what could as well be an alien space.

Kọ́lá Túbọ̀sún

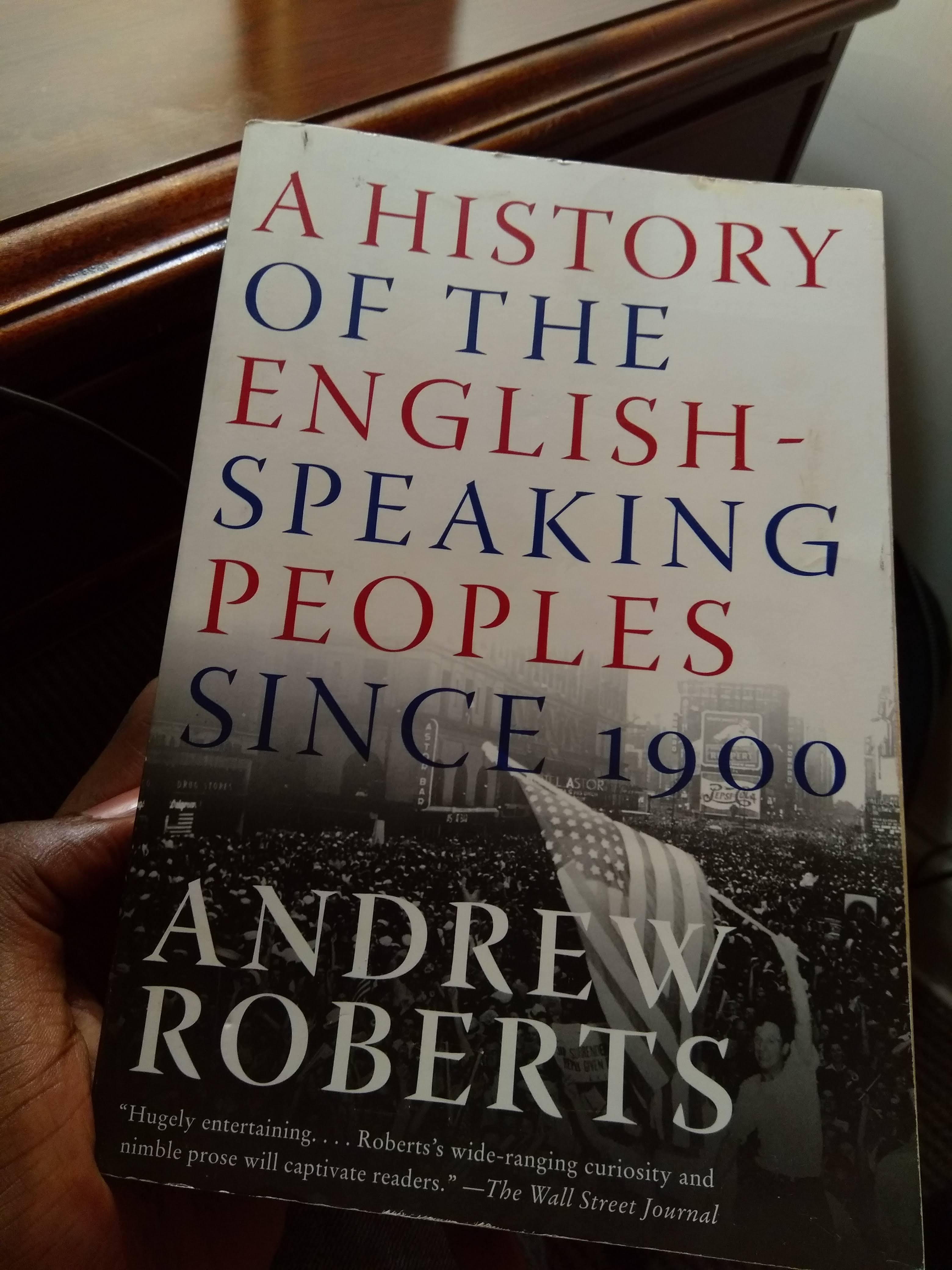

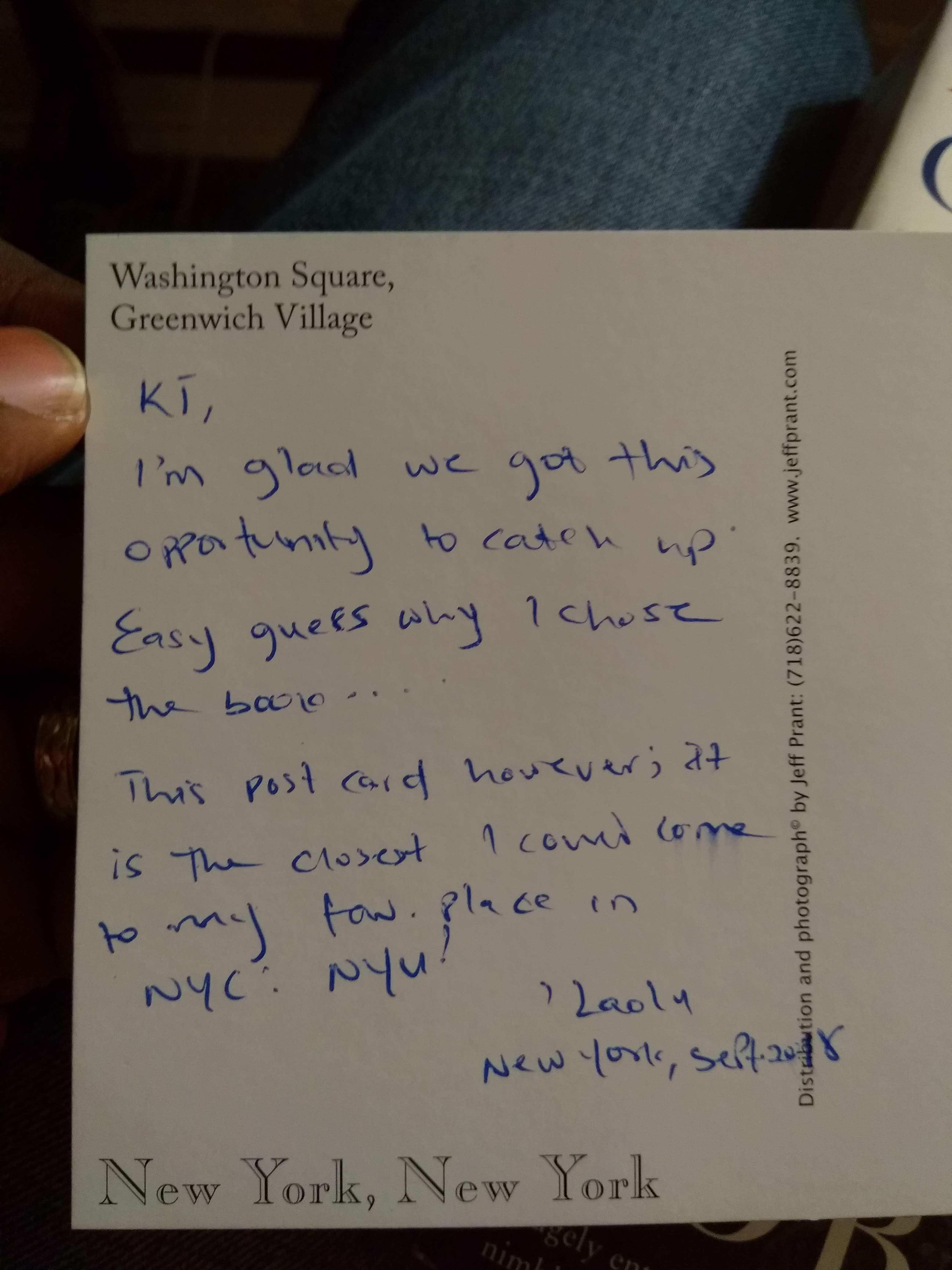

Kọ́lá Túbọ̀súnỌláolúwa had had brought along a book for me titled A History of the English Speaking Peoples Since 1900 by Andrew Roberts. Unexpected joy. Then we walked around into Central Park, just two streets away, which smelled of horse shit, and then to 5th Avenue and Trump Towers, which didn’t, as much. Instead, crowds gathered around at the junction, staring at the black structure in the dark night.

The president was in there, very likely, because the street had been shut off and vehicles rerouted to other paths. Heavy trucks blocked the entrance to the building. If Mr. Trump or any of his tenants or family members had strolled out into the street, they could have avoided detection by walking behind the trucks. Other figures moved around in the night, likely undercover security men.

Nothing more to see except the back of tourists’ heads all facing a singular direction. We headed back, found a Starbucks which didn’t have a problem with us not buying anything for as long as we sat, two merry Nigerians chattering loudly about every available subject, into the night.

Kọ́lá Túbọ̀sún

Kọ́lá Túbọ̀súnKọ́lá Túbọ̀sún