The singular cultural phenomenon now known as World Wrestling Entertainment had already been around for decades when it alighted on British television screens in the early 1990s, via the recent transatlantic import of cable TV. For kids like me, it became a fleeting obsession, peaking with Wrestlemania VII, which took place in the Los Angeles Coliseum on March 24, 1991. A day or two later, I watched a morning rerun of this annual extravaganza at a friend’s house, where we deposited all the sofa cushions on the floor so we could reenact the suplexes and piledrivers in tandem with the action in the ring.

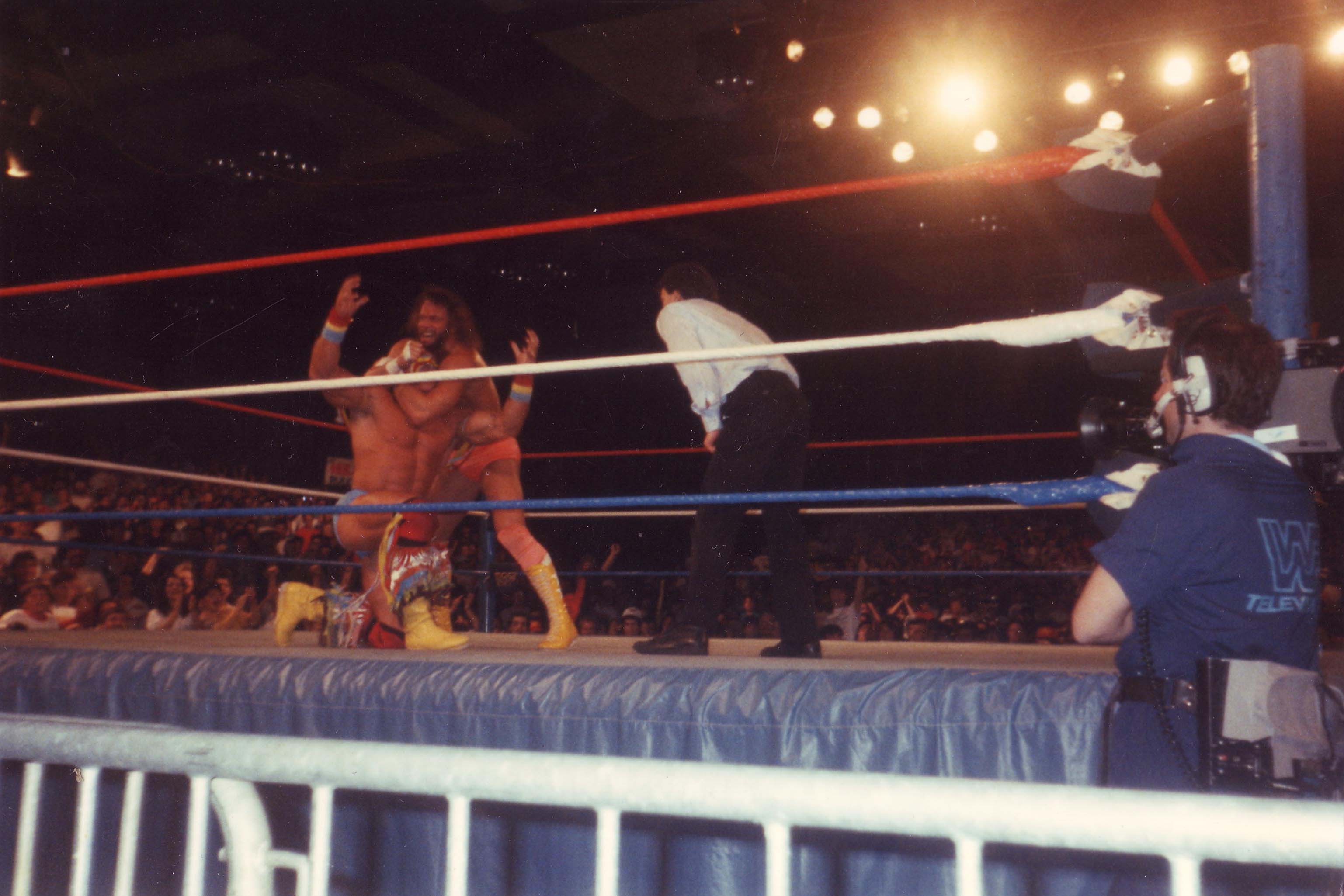

Among the most anticipated encounters was a “retirement match” between “Macho Man” Randy Savage, an unhinged all-American antihero, with big hair and a lumberjack’s beard, and fan-favorite The Ultimate Warrior—picture an American Indian chieftain on amphetamines—who was known for his half-crazed demeanor and his superhuman ability to body slam all 500 lb of Andre the Giant. The stakes were high: to settle an ongoing feud, the loser would have to hang up his leotard for good. Savage entered the arena in a wide-brimmed hat and white spandex trousers. Warrior followed him in, snarling in tasseled pink boots and fluorescent face-paint. The bell rang.

Unfamiliar with the WWE script—unaware, at this point, that there was a script at all—we thrilled as the fight swung this way and that. For much of the match, Savage, cast as the villain, appeared to have the upper hand. But then, channelling, as we were led to believe, some divine life-force begotten by his Mohican ancestors, Warrior was revived. After some trademark rope-shaking and foot-stomping, Warrior bounced off the ropes to shoulder-charge Savage in the head several times in a row. Finally, with Savage concussed and prostrate on the canvas, Warrior placed a boot on his chest. The referee slid to the ground for the three-count, and Warrior, his bespangled arms held aloft, basked in the hollering and applause.

The drama wasn’t over. For Warrior’s defeated adversary, succor came in the permed form of his estranged girlfriend, Elizabeth, who’d been watching from the crowd. When Savage’s demented manager, The Sensational Queen Sherri, added insult to injury by castigating and assaulting Savage, Elizabeth entered the ring to intervene… okay, this is all getting rather complicated, but all we need to know is that Savage and Elizabeth were reunited, then carried offstage on a dais to the strains of “Land of Hope & Glory.” Members of the crowd wept tears of joy. This was soap opera and high-octane sport in one. My God, I was sold.

For the next week at least, the schoolyard was abuzz with chat about the American spectacular. Until one older boy explained, with the pomposity of a sage popping a dozen delusions, that the whole thing was a sham. What had, to my callow child’s mind, seemed like a kinetic martial art, was all masquerade, the fighters just stuntmen in tight-fitting trousers.

It seems hard to fathom, against the polarizing backdrop of Trump’s America, that the United States in the spring of 1991 was a place most people in the west looked upon with a fair degree of admiration and awe. The Berlin Wall was rubble; communism in its death throes. Saddam Hussein, western democracy’s enemy du jour, had just been chastened by Operation Desert Storm in the Gulf War. America’s grip on international geopolitics seemed unassailable, as Fukuyama’s “End of History” thesis became a reassuring axiom of irreversible democratic stability. But for kids, more pertinently, American culture had established a global monopoly.

The America we saw on the screen and on the billboards was the country where everyone lived in big houses, and the good guy always won, if not immediately then at least before the credits rolled. It was the eternal sunshine of Flipper, Baywatch, and Beverly Hills Cop; it was the preternatural talent of Madonna and Michael Jordan. It was the virility of Mike Tyson, and Schwarzenegger dispatching dark foreign armies single-handed. The fantasy-land of Knight Rider, Ultimate Warrior and Cindy Crawford’s mole.

It was all such an antidote to the drizzly austerity of post-Thatcher Britain. We had our own wrestling, shown each Saturday as part of a sports round-up program, generously titled “World of Sport.” But while American wrestling burst from the screen in a pageant of glamour and super-sized stadiums, our version looked as though it took place in a drab town hall on a Monday night. Its stars were Big Daddy and Giant Haystacks, chronically obese men in home-stitched leotards, bouncing into each other with jolly bellies of pie and ale.

Is it any wonder that we revered the brash superpower across the Atlantic? At school, it wasn’t unknown for kids to fib about having American ancestry in order to elevate their social capital. Me, I claimed to be quarter-American, augmenting this falsehood with the yet more dubious one that my single mum drove a Rolls Royce, which perhaps evokes something of the yuppie preoccupations of the wealth-obsessed period I was growing up in.

It should go without saying that ours was an abbreviated view of American life, circumscribed by a youthful lack of interest in history and news. We didn’t know much about Vietnam or the civil rights movement, not to mention the War on Drugs or the L.A. Riots. The Cosby Show and Fresh Prince of Bel Air played each week on terrestrial TV, and the African-Americans on our screens seemed to be doing just fine.

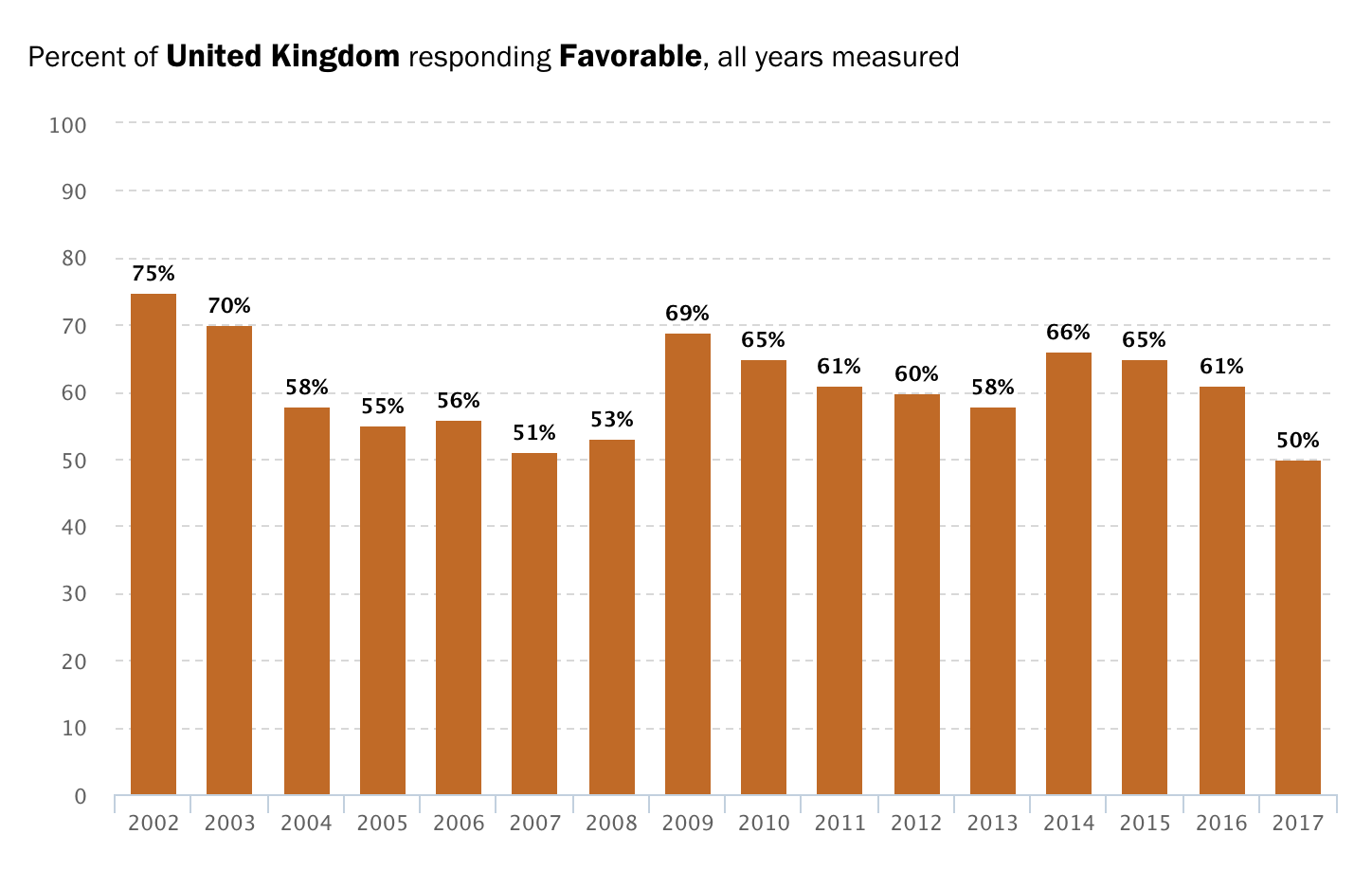

During the administration of George W. Bush, Pew Research Center figures suggest that the proportion of Brits with a favorable view of America fell from 83% to 53%; under Trump, it’s fallen to 50%. “In Europe, the view that America is part of what has gone wrong in our world, rather than a force to help make it right, has become all too common,” said Barack Obama, during a 2008 speech in Berlin. But by then even the note of self-awareness that accompanied Obama’s election could do little to resurrect my fantasy of America. People hung on the symbolism of his historic victory and the promise of his stirring oratory. But to me, in the polarities of that 2008 campaign, the rumblings of conservative America’s descent into madness were already audible.

After the War on Terror exposed the lie of its moral superiority, after Hurricane Katrina exposed the nation’s contempt for its hidden underclass, America no longer seemed like a place to be envied. It was the country of Sarah Palin’s folksy, gun-fetishizing patriotism, and Fox News sophistry. And it was a country where grown men, holding foam hands and crude banners, drinking watery beer, yelled in support of steroid-pumped actors in spandex pretending to beat each other senseless with moves like “The People’s Elbow” and “The Socko Claw.”

Wrestlemania VII had presented a world whose protagonists could throw punches without consequence. It was a world where the abusive tirades and trash-talk caused their subjects no real anguish, and even bad guys like Sergeant Slaughter, a perma-grimacing paramilitary who lost his world title to Hulk Hogan in 1991, could oscillate between villainy and heroism over the course of one week’s plotline.

No real values held in this world. Unsurprisingly, a few months after Warrior ended his career, Randy Savage was back in the ring.

In WWE footage from decades past, Donald Trump can be seen making multiple cameos, most famously body slamming franchise owner Vince McMahon in the “Battle of the Billionaires.” In 2013 Trump was granted admission to the WWE Hall of Fame.

Wrestling, with its belligerent posturing and inconsequential violence, came to seem to me a template for the unravelling of America’s national conversation. Superficial analyses of Trump’s rhetoric describe him as just a politician, “lowering the tone” or “telling it like it is.” But what he really does is far more radical. In a culture saturated with media and make-believe, Trump’s pantomime style blurs the line between theater and reality, WWE style.

When I watch footage of the Warrior-Savage fight now on grainy YouTube clips, the theatrics, the ebullient personas, and the extravagant stage combat look preposterous. But cheering for those muscular clowns was fun. I’d wanted to believe the show was real. The good vs. evil, the neat Manichean frame—was comforting. It gave us reason to cheer, to lose ourselves, and it was so fucking dumb and mad that it was easy to convince yourself that none of it mattered anyway.

I often wonder whether Trump’s appeal—the mysterious quality that keeps his supporters loyal—is the one you feel when you’re a child, watching a 280-lb meathead dressed as an American Indian chieftain shoulder-charge a bad guy in the head three times in a row.

On October 18th, a few days before the shootings in Pittsburgh, Trump stood at a lectern at a rally in Montana and joshed offhandedly about how Congressman Greg Gianforte’s assault on a reporter going about his job was a thing to be applauded.

“Any guy that can do a body slam,” he said, as the gallery behind him chuckled along, “…He’s my guy.”

Henry Wismayer