At university, I joked with people who didn’t know where White River was, saying that all you need to know about the dorpie is embedded in its name: “You’ll find whites and rivers if you come visit me.” An actual river runs white, just off the R40 headed to Casterbridge, a lifestyle centre for laanies. In grade six geography we learnt that the river runs white because of the kaolin-rich rocks that line the riverside. In the rainy season it supposedly flows a creamy white colour.

My father was in the Tricameral Parliament in the 1980s when the National Party sought to appease South Africa’s buffer races—people racialised as Coloured and Indian—and included them in lower-rung governance structures. When the government asked him to relocate from KwaZulu–Natal to Mpumalanga in the mid-90s, he accepted. I was three when we moved to White Water. Initially, we lived in a trailer park on the outskirts of Mpumalanga’s capital city, Mbombela. I don’t remember much of my time there, but I do remember the woodcutter’s cottage we moved to a few months later. It was across the street from the trailer park and consisted of six log cabins on a large plot in a timber plantation. I’d often play on the piles of timber that were kept on one side of the plot. The smell of freshly cut wood still catches me in my throat.

White River was known as Emanzihlope by the Swazi for decades before the Afrikaners and English came to the area, and named it Witrivier and White River, respectively. They settled into the area as farmers, and, in fact, HL Hall & Sons, one of South Africa’s largest agricultural companies, was started in White River.

My favourite part of driving through town is entering White River. You come in on a hill, and descend with tall palm trees flanking either side of the R40 road. The old magistrate’s court stands in the centre of town, and everything radiates outwards from there. The police station, post office, municipal office and library are all on the same street, a few metres away from the court. The Dutch Reformed church, Kraaines (a second-hand furniture shop), and the local Wimpy and Engen garage stand farther out. And on the outskirts is where people live.

My younger brother, the only Appasamy born in Mpumalanga, the province that White River is in, had his first hair put in the river that runs white. It’s an old Hindu custom: a newborn is shaved, and their first hair is placed in the sea to get back to the Ganges. We couldn’t go down to Durban to perform the ceremony with a priest, so we parked off the main road and placed his hair in the river ourselves. We sang one or two Tamil songs—I mumbled—then left, feeling lucky we didn’t bump into any green mambas who love the tropical habitat of mango plantations that lined the R40 back then.

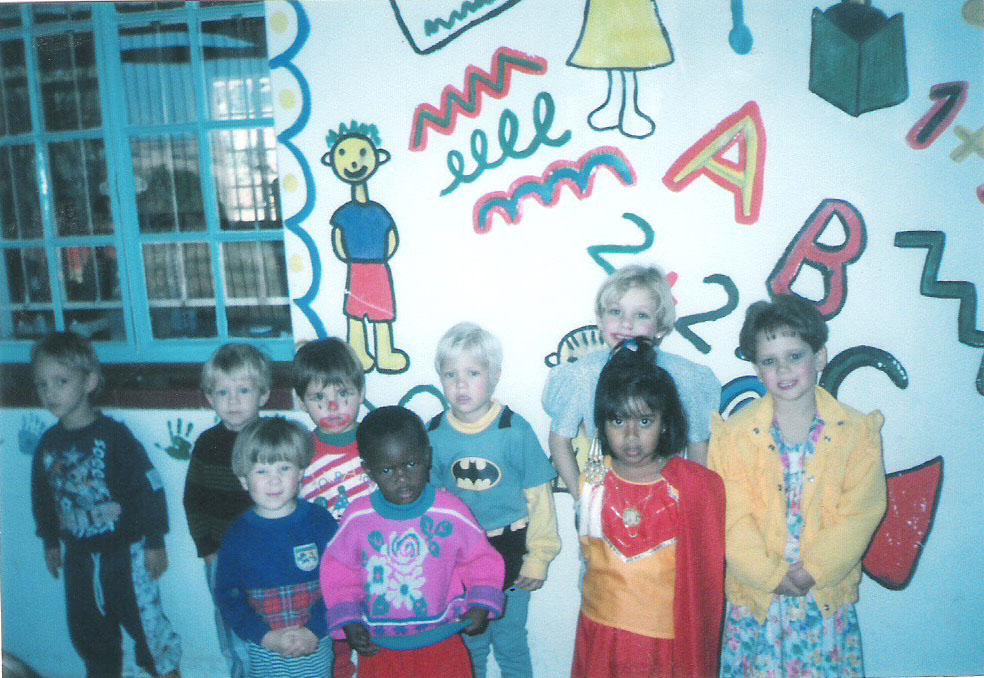

In 1997, my parents found a flat in White River. Our block of flats was called Inyoni, and it was close enough to walk to all the important places—the library, school, and Pick ‘n Pay. In my primary school, classes were divided along English/Afrikaans lines, and so my interactions with Afrikaans children were limited. When I was in grade seven, a new dual-medium method was instituted. The kids with the highest marks in English and Afrikaans were picked to opt into a new class, where teachers taught equally in English and Afrikaans. Our teachers, who mainly taught in Afrikaans, favoured the Afrikaans lot and gave them easier tests, or offered them extra help.

I learnt how to read Afrikaans before English, mainly because almost all the signage is in Afrikaans and it’s straightforward enough to learn with its guttural sounds. English is a lot trickier, with silent q’s and complex vowels. Similar to the language, Afrikaans people are straightforward, and will tell you that they don’t like you because you are a koelie or Hindu, or both. In a conservative Christian town such as White River, these are two very dangerous things to be. When I was in grade four or five, I remember waiting for my mum to pick me up after school with some friends around the tuckshop. A barefooted Afrikaans boy asked me if I was a koelie. He then proceeded to run around shouting out the word koelie over and over again, until my group and I went out the school gates to wait. I didn’t know what the word meant, so I kept the incident to myself.

Meanwhile, English people would invite you into their homes and then ask invasive questions about how you smell and tell you how they’re sad because they won’t see you in heaven. After these visits, I’d ask my mum why she was allowing me to go to hell by being Hindu. One friend couched her evangelism in trying to find out about Hinduism, only to get ammunition on how and why it contravened Christianity. Praying to the Shiva Lingum turned into stone idol worship, praying to a monkey was absurd, and I went quiet when religion was brought up in a bid to remain friends. My mum told me to stop talking to that friend, but I didn’t listen and went through years of her trying to convince me that although she loved me, I was still a heathen.

My social world was firmly white: white teachers, white music, white friends, white neighbours. Although this was alleviated slightly by my more cosmopolitan private high school, the terms of engagement were white and I internalised that. In my teenage years I rubbed a mixture of turmeric and lemon water all over my face, arms and legs every month or so. I thought if my complexion was lighter I could avoid attention, or detection.

I don’t think my parents realised what kind of effect institutionalised and everyday racism has on a child, but maybe they were too homesick to realise. Diwalis were a muted and ordinary time, and until I was 15 we would let off a box of firecrackers until the neighbours complained that the crackers hurt their dog’s ears. My parents spoke of Diwali in Verulam wistfully, and my brother and I listened earnestly as we played with sparklers. Whenever we went to Verulam, my dad would go to the local Kara Nichas and stock up the car with boondi, chevra, gulgulas, and chana magaj—a taste of home for him.

Both my parents were born in Verulam, went to public schools for Indians, and lived with their extended family around them. Verulam is their hometown, and sometimes I mistake their feelings of longing for my own. As a child, I went to temple every Sunday, had sleepovers with my cousins, and went to the Morning Market to buy vegetables and spices with my aya. Even though I was three when we packed up and left to live in Mpumalanga, the school holidays and Decembers spent there left an imprint in my mind.

It’s not unusual to be a charou in Verulam—a town 45 minutes outside Durban, KwaZulu–Natal’s capital city. I liked the anonymity of walking with my parents and not being stared at. I blended in, until I shaved my hair and dyed it pink.

Verulam is surrounded by our generational trauma. The sugarcane grows thickly around the town, and if our ancestors didn’t work in the plantations, neighbours’ did. In the 60s the town was declared an Indian–only area thanks to the Group Areas Act, and my mother’s side came to the town after being forced off their homes inland, in New Germany and Wyebank. Because of this policy of separate development, Verulam is still known as a charou zone. My maternal grandparents went to India once, and according to my aya, the people were rude because my grandparents were from Africa, westernised, and dark-skinned. “Too dark for even a Tamil, they said,” she recounted. In Verulam, you talk about India people and charous. India people came here to open businesses in the late 80s and early 90s, and charous are descendants of indentured labourers.

The South African Indian tabloid, The Post, regularly published a cartoon called Peru and Bala. The cartoon features two old Tamil men from Verulam. My dad’s brother knows the real-life Peru and Bala, whom the comic is based on, and apparently, they used to live in a tin–and–brick shack in town. Peru and Bala are a duo out of time, and in many ways, Verulam feels like that too. Cranky and elderly, struggling to comprehend what a new South Africa means when they were just getting used to life under apartheid.

Peru and Bala’s now-demolished house was close to the Shri Siva Subramaniar Alayam, or Drift temple, a place to which the Appasamy side has strong ties. It’s a beautiful, crumbling structure on the banks of the Mdloti River, and there are usually stray cats and dogs on the grounds who are fed by the priest. One time I saw a peacock preening for the congregation after Sunday service. The temple is an unfussy place, and the colours of the murtis have faded, but a stay in Verulam isn’t complete until I take a walk around the temple and pray. My paternal thatha was chairperson of the Alayam for a few years in the 70s, and both sets of grandparents spent much of the money they made on rebuilding the temple after floods or termites, teaching Tamil and English, and generally being present. My parents were married in the adjacent hall, and many memorials for family members were held here. My first hair was placed in the Mdloti River.

Recently, I was in Verulam for a family event. My parents and brother made the slow eight-hour drive from White River to Verulam, and I flew down from Johannesburg, which made me feel oddly adult at this family gathering. When we arrived at Drift temple for the service on that humid night, my younger brother and I caught up, and were planning what meat dish to break our fast with. After a late-night tea, and with our parents chatting to the aunties and uncles, we went our separate ways and wandered around the dark temple grounds. As the wind carried the smell of the river, I thought Maybe the Ganges ends up here.

Youlendree Appasamy