October 25, 2018

City of London, England

All I took with me on the tube were my eyedrops. I had stopped trying to wake up in the morning and they were the only thing that stood between six to eight hours of staring at 19th century handwriting and my eyes falling out of my head.

Commuting to historical archives is the ultimate exercise in urban loneliness. When I get off the tube, I’ll become intimate with the the long-dead through textual traces, but the people crammed next to me on the tube were entirely illegible. The only clue to their humanity was what they were reading. I had to fight back the urge to slap copies of Yuval Noah Harari books out of people’s hands and scream at them “READ A REAL HISTORIAN!” I stayed quiet.

The financial district of London (the City), where I do most of my research, is not conducive to strangers. The bros of finance are smoking in the alleyways in small groups. As a poor American graduate student in jeans and a sweater, I might as well be walking around with a neon sign that says “I DON’T WORK IN FINANCE.”

I arrived in the City at the one place I belonged; ironically, it was also one of the most secretive and exclusive banking houses in the world: the Rothschild’s. Two massive art installations at the front of the Rothschild’s dominate the cramped vista of St. Swithin’s Lane. One is a large painting of a happy Rothschild family in 1821, playing with their dog. The other is a massive biblical tapestry of Moses and the brazen snake. A tourist tried to take a picture and was quickly accosted by one of the Rothschild’s security guards. No pictures. The tourist was promptly directed out. The other security guard gave me a pleasant nod. I’d been here before. I knew the rules.

I was ushered past two levels of security, and the archivists left me alone in the cavernous reading room with a cart full of boxes that I would be hard-pressed to finish in a month, let alone the remaining weeks of this research trip. I was more tempted to browse the books on the wall or examine the gold bars on display next to me. Anything to stave off reading thousands of pages. The sheer scale of historical archives does as much to occlude the past as it does to reveal it.

Yet in the countless back-and-forth dispatches between far flung agents—the operational backbone of 19th century finance—I found some surprising signs of life. The mercurial anger of Nathan Mayer Rothschild, who founded the London house in 1804, is well-known. But I found his oft-abused agents endearing. Some were indignant and others tried flattery, sending unsolicited barrels of pecans or, better yet, portraits of American presidents. These were not always appreciated. A gifted portrait of Andrew Jackson languished in the Rothschild vault until the mid-2000s, merely labeled “American military officer.” I speed-typed notes.

There are many letters that the writers never expected to be kept. They are stamped “PRIVATE” in red ink, though here I am. In 1848 one agent was acting covertly to foment political agitation against an unfavorable legislative bill. “When all is achieved,” he wrote “it will be a gloried day with me, although in all this my acts remain in the shade, and are no doubt destined there to remain.” In another private letter, two agents exchanged personal greetings.They inquired after each other’s wives. “I trust the relaxation of a few days in the country has not been forced upon you by too close application to your desk,” one wrote. I sympathized.

My rhythm of speed-reading and typing was broken by the archivists. It was early, not closing time. I protested; after all, I knew the schedule. “There are clients in today. We have to give them the tour,” they told me. Leave it to finance to monetize even its archives.

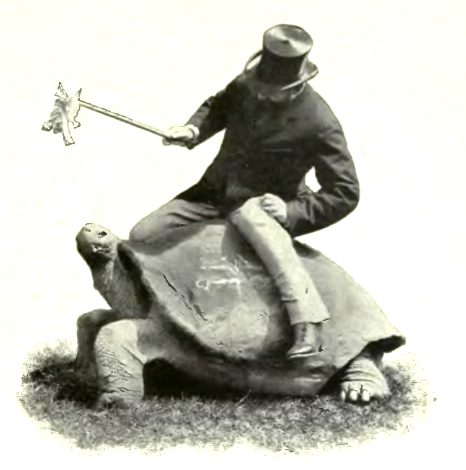

As I packed up, I watched as the Rothschild family’s best memorabilia was assembled. My favorite artifact was a photo of a portly Rothschild in a top hat, riding a tortoise. “That’s Walter,” the archivists told me, as I looked. Walter was so bad at banking that his father let him leave the family business and start a zoo.

Attempting to demonstrate that I too had detailed knowledge of the family, I asked if they had any pictures my favorite Rothschild, Mayer Amschel. Nicknamed Muffy, he weighed 16 stone and, like Walter, was more known for his failure to join the family business than any actual accomplishments. He preferred horse-riding and hunting to banking. “We don’t really talk about him,” the archivists told me. Family black-sheep die hard.

The clients arrived in the lobby of the reading room and I was ushered out a back-door, rarely used for guests. It was, in fact, a secret door of sorts: a plain white section of wall between the two works of art that hung facing the street. Uninitiated passerby shot me strange looks as I materialized. The security guard gave me another knowing nod. After all, I knew the rules.

On my way back to the tube, the bros of finance had moved from back alleys into pubs. I considered one briefly, but as in their smoking circles, I did not belong. The tube was crammed. It was almost rush hour, and I just barely managed to squeeze on board. 45 minutes of a hot and loud ride later, I arrived back to a dark and quiet house. After dinner I opened my computer to review my notes. The people that populated them were, after all, the liveliest things I had encountered all day.