I remember the first time I saw a roti parcel. I had snuck away from the archive and left behind the metropolitan bustle of Suva: its storefronts and teeming malls, its buses without windowpanes belching out diesel fumes, its handful of concrete high-rises. I was in Fiji doing research for my dissertation, and after three weeks of the archive’s regimented time—requisition documents, struggle to read nineteenth-century handwriting, get fingers coated in one hundred years’ worth of dust, repeat—I was going a little batty.

UNESCO had just added the old capital of Levuka to its World Heritage list, so I thought that my escape could combine a needed break with an extracurricular history lesson. I had to get to the small island of Ovalau, so I took a bus to Natovi Landing, a small patch of concrete set amongst lush green bush and lapis water. There, I waited for the ferry, an old hand-me-down from Greece. A lanky man came along selling foil-wrapped snacks. Feeling the hunger-boredom of a long journey, I bought one: it was potato curry wrapped in a roti (a thin unleavened flatbread) the size and shape of two decks of cards. I took a bite.

In a place so remote, looking out to where the blue of the water met the blue of the sky, eyes scanning for the first sight of the ferry, I suddenly felt very close to home.

Indian food: a curry, a tikka masala, a dosa, a naan, a roti. A roti? Of course a roti. For Trinidadian or Guyanese immigrants in Toronto, New York, or London the comforts of home can be found in the roti shop. And even more—a bunny chow. Any South African from Natal could name his or her favorite place to grab a bunny chow.

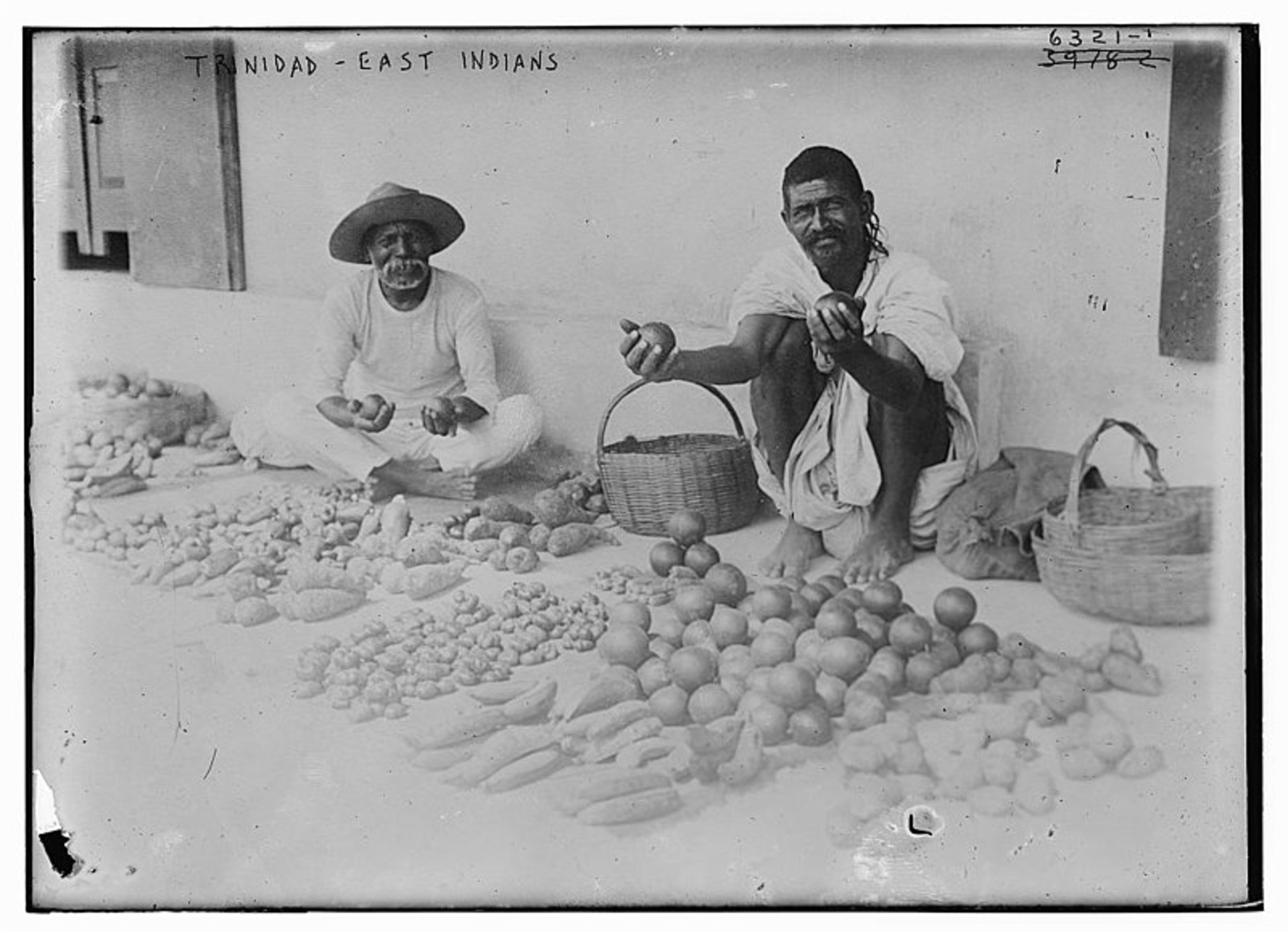

Much of this food originated when Indians were sent around the world as indentured servants. The history of Indian indentured servitude dates back to the 1834 abolition of African slavery in the British Empire. In theory, these plantation owners could have hired emancipated slaves, but few of them wanted to pay fair market wages for a day’s work, so they convinced British officials to create a new system whereby they could again procure pliant and cheap labor.

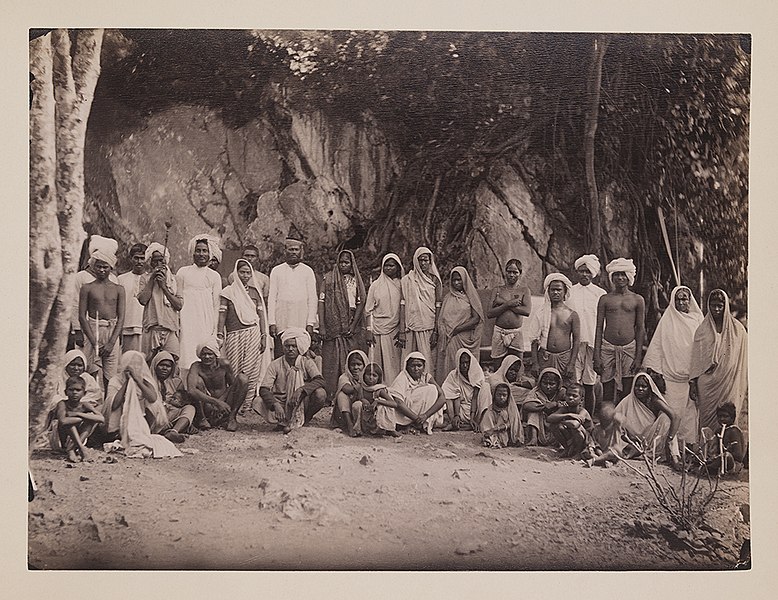

In 1838, plantation owners and imperial administrators created a subsidized global system to transport Indian laborers to sugar plantations in Mauritius and the Caribbean. The system would not be abolished until 1919. By then, almost two million Indians had been sent to the Caribbean, South and East Africa, Southeast Asia, and the South Pacific as indentured servants.

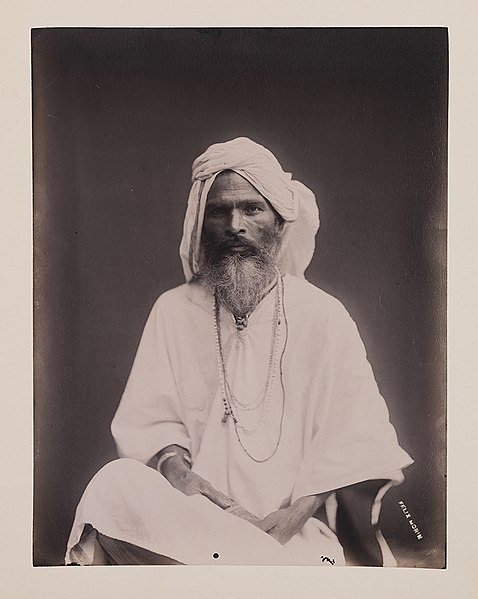

The phrase indentured servant seems almost too proper, with its strong whiff of legalism. Indians were rarely called this. More commonly they were denigrated with a spat-out word: coolies. Disgust for this word rang through folk songs. One from British Guiana complained:

Why should we be called coolies!

We who were born in the clans and families of seers and saints.

Many of these migrants referred to themselves as girmitiyas. The word was creolized Hindi referencing the English word agreement. Knowing that they were bound by contracts to labor on plantations, they gave themselves a new name. Not coolies, not Indians, but girmitiyas.

I was in Fiji, and later Trinidad, to study this history. I had started a PhD in history and quickly wanted to drop out. I was a novelist in the wrong place, and with a boring project to boot—something about mid-nineteenth-century colonial educational policy. But, I stuck around and decided to change my research to something that felt more like home.

My parents are from Bihar in Northern India. It’s India’s poorest state and rarely on anyone’s Eat, Pray, Love itinerary, though it does have the peepal tree where the Buddha gained His enlightenment. I remember being a kid, sitting in a ramshackle airport in a backwoods corner of the state, biding my time on a Game Boy as we waited to board a flight to some uncle or cousin’s house, and looking up to see groups of Japanese tourists exiting a jetway on their tour package to Bodh Gaya.

While my identity to other Americans of all ethnicities is straight-up Indian (or rather, South Asian), I am first and foremost a Bihari to other Indians. I grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area when it was less Indian and significantly less Bihari. It felt like my parents knew every Bihari in the nine-county Bay Area region, and they formed little groups and associations that split and fractured with every whim and ego. When it came time to stay in graduate school and find a research topic, I wanted to learn the how and why of people like (but not exactly like) my parents. I wanted to spend my time in places I never imagined going, studying those who left India to go to places they never imagined either.

Many of the girmitiyas were from the peasant classes. Most hailed from Bihar and eastern Uttar Pradesh. My mother was born and raised in Patna. It was more or less a small-c capital when she was growing up, but is now a city of 2.7 million people. My father was raised in a village with a name as pastoral as its fields of sugarcane: Mairi Makhsuspur. It’s located in the Siwan district, but back in the colonial days was part of the Saran district. Thousands, if not tens of thousands, of Indians left this district for the indenture colonies. Though my mother and father left India in the late 1970s, it is almost without a doubt that some relatives of mine left that district between 1834 and 1919. The mathematics show no other way.

Why did they leave? British policies regarding land ownership left the Indian peasantry in these regions in massive amounts of debt. In came a recruiter from the city. He promised stable jobs and higher wages. Sometimes he mentioned that the job was across the kala pani—the black waters that were said to destroy a man’s caste and all his filial attachments. Sometimes the recruiter just mentioned that the job was somewhere else. But it was all about the money anyway. The recruiter said that the pay was 1½ shillings per day, almost 25 times the wage a peasant could find inside India. Who wouldn’t sign away his life for that?

The recruiter took them to Calcutta. They sat in a depot with the other migrants, separated by gender, as they waited for their departure. The depot turned rural Indians into indentured laborers. As the journalist and historian Gaiutra Bahadur put it in Coolie Woman, “the system took gardeners, palanquin-bearers, goldsmiths, cow-minders, leather-makers, boatmen, soldiers and priests with centuries-old identities based on religion, kin and occupation and turned them all into an indistinguishable, degraded mass of plantation laborers without caste or family.”

They sailed down the Hooghly River into the Bay of Bengal, and watched their homeland fade from view. The journey from India to the Caribbean could take as long as 200 days without steam power. Men and women were separated, though this did little to safeguard women from abuse. They were often molested or raped by the sailors, captains, and officials on board. In the end, the black waters drew some to jump overboard.

Once they arrived in the indenture colony, Indians were sent to work on sugar (or rarely, cocoa) plantations for up to five years. The labor was backbreaking—hours spent weeding, tilling, and cutting cane. Diseases such as hookworm were rampant. Officials sent them to prison for petty violations of their indenture contracts. The stresses of plantation life meant that girmitiyas were often taken to the brink of sanity in a world that cared little for their well-being. They summed up their life with a single word: narak (hell). But their contracts required five years of labor. If they wanted a free journey back to India, they had to sign up for another five years of narak. Most were unable to stomach the thought. They never left.

These colonies offered a chance to build anew. Some remained on or near the plantations and afforded themselves the comforts of a routine they had come to know and hate. Others shed their past identities, both as rural peasants and as girmitiyas. They became catechists, teachers, landowners, or clerks. Some even became shopkeepers, greengrocers, or cooks.

But what would they cook? What would they serve their Indian customers? What they invented anew was always tinged with the past. They had just come from plantations where their memories were turned into meals that fueled them through long days of cutting and milling cane. In the years after indenture, these meals took on elements of the old world and the new. The sons and daughters of girmitiyas created a new style of cooking, one that was both Indian and not. This was the food that would speak to their ancestors, their lives, and their new homes.

What did the girmitiyas take from India? Usually, it was whatever they could fit in their small jahaji bandals (jahaji: literally sailor, but in this case a seafarer or traveler; bandal: bundle) filled with nothing more than a few pounds of assorted items. Brinsley Samaroo, a historian of indenture, found that in their sheets tied upon sticks, girmitiyas stuffed fruits, vegetables, and flowers: aam (mango), Tamar-e-Hind (literally, “dates of India,” now known as tamarind), legumes, peppers, spices, and more. They planted old seeds in their new homes.

I remember being 16 and reading Jhumpa Lahiri’s The Namesake. Of all the scenes in that book, one, its opening, remains indelible. In a humid summer kitchen stands Ashima Ganguli, mixing together Rice Krispies, Planters peanuts, salt, lemon juice, green chilies, and red onion, trying to make an approximation of jhalmuri to satisfy a pregnancy craving. Every migrant has a craving. Every migrant has to make do. The girmitiyas were no different.

In his documentary Dalpuri Diaspora, Richard Fung explores some of the ways in which recipes and food traveled from India to the Caribbean. For example, he found that migrants couldn’t find any dhaniya (cilantro), but they did find an herb that looked like it. What substituted for dhaniya was culantro, rechristened by the girmitiyas as bhandaniya (shrub cilantro). The thick leaves of the culantro stand in stark contrast to the delicate cloves of the cilantro plant. The taste is also less pronounced than cilantro, yet more herby, and more green. This was in contrast to Fiji, where Indians brought dhaniyain their jahaji bandals. The Fijian language lacks a word for cilantro, so to this day, all in that island nation refer to cilantro as dhaniya.

This willingness to swap is evident in the spice mixes essential to Indian cooking. The quintessential spice mix of South Asia is garam masala, the mix of cumin, coriander, cardamom, peppercorn, cinnamon, clove, and nutmeg. But the curry powders in the indenture colonies spoke to the ingredients on hand. Curry powders in the Caribbean and Fiji, for example, use a significant amount of turmeric in their mixes. The South African Durban curry powder uses a mix of chili powder, ginger, garlic, coriander, cumin, cardamom, cinnamon, and fenugreek.

Rotis, chapatis, naan, and puri (various kinds of flatbreads) in former indenture colonies are—to this day—cooked with white flour. This is in stark contrast to the roti of South Asia, which is cooked with atta, a high-extraction whole-wheat (brown) flour typically made from durum wheat. “The use of the white flour as opposed to the use of the atta—the brown flour—is really a question of availability,” Samaroo recounts in Fung’s documentary. “In the nineteenth century the white flour was brought not from India, but from North America. First the Thirteen Colonies, which exported flours and other things to feed the slaves in the Caribbean . . . And after the American Revolution . . . the flour continued to come in, but from the prairies of Western Canada, and that was always white flour.” This makes sense, given whole-wheat flour’s short shelf life. White flour could survive the long journey across the ocean without spoiling.

Instead of the roti being used as a vehicle for the main dish, the main dish itself was put into the center of this roti. The roti was then wrapped tight, offering a hearty meal that could be eaten on the go: a quintessential Indo-Caribbean dish.

The theory behind this transformation has traditionally been that the wrapped roti was a way for indentured migrants to eat while they toiled on the plantation. Fung isn’t so sure this is true. “The everyday roti, sada [plain] roti isn’t thin or pliable enough to be folded,” he mentions in his film. “No one knows for sure, but it seems most likely that the wrapped roti is a commercial invention.”

Strangely enough, the wrapped roti appears thousands of miles away in Fiji as well, where it is known as roti parcel. The basic mechanics of the dish remain the same—a white-flour thin roti filled with vegetables, meat, or a combination of the two.

Perhaps the dishes share a common ancestor. The historian Lomarsh Roopnarine argues that some Indians who did return to India after their indentures were greeted as pariahs. Ten years in a far-off place with a strange social structure and meals filled with meat, rum, and fish marked these Indians as foreign, and they no longer fit in with their old villages. So they reindentured themselves and were sent off to new indenture colonies. It may have been the case that one of these reindentured Indians tried one of the wrapped rotis in an Indian-owned shop in the Caribbean and then introduced the meal to Fiji.

But most of the new dishes that have come out of the indenture colonies have been, as Fung points out, commercial inventions. These have been the meals made by new generations—those born in the colonies and not weighed down by the visions of what past recipes looked like in the motherland. These shopkeepers and cooks were willing to experiment with what they knew and what they could make.

Take, for example, doubles in Trinidad. Introduced in the 1940s, they were—and remain—a popular morning street food for those on their way to work. The first doubles makers took the vada, a fried savory doughnut made of legume flour, and changed the ingredients. The legume flour was replaced with all-purpose flour and baking powder. This vada was then rolled out as a flatbread and fried. Two of these fried breads (hence the term doubles) were taken and topped with curried chickpeas, tamarind chutney, and hot pepper sauce.

Even more creative was the bunny chow. The Indian community in South Africa mostly resides in KwaZulu-Natal. The bunny chow took its name from the bania community of shopkeepers. And chow, of course, meant food. The meal was essentially a bread-bowl curry: a half- or quarter-loaf of bread was hollowed out and a goat or vegetable curry was ladled inside. The bunny chow was a to-go meal for the Indian community in Durban. Barred by apartheid laws from eating in restaurants, they needed a full meal that could be eaten on the move.

Girmitiyas and their descendants did not create facsimiles of the food of India. They did not live their lives in hopeless lockstep with a homeland left behind. They used Indian spices, Hindi-language names, and Indic-style fillings, mixing these with white flour, bread, and culantro, taking what they knew and combining it with what they didn’t.

This all brings me back to the roti parcel I savored as the ferry chugged along the blue waters. When I was a kid, Indian restaurants were opening up here and there. A classmate who had eaten his first chicken tikka masala would inevitably ask me, “Do you eat Indian food at home?” I wanted to say no; or yes, but not what you’re thinking. I usually just said yes and that was that.

A better answer: I think of how Thanksgiving came to be in my family. My parents knew nothing of the holiday for their first five years in the United States. When they moved west from New York to California, they fell in with a group of Indians who celebrated it. Soon enough, it moved into our kitchen. My father cooked the turkey, but instead of filling it with a bread stuffing, he made one with what he knew: aloo, mattar, tej patta, mirchi, and a mix of masala. It’s somewhat akin to a samosa filling, but stuffed inside of a bird. This stuffing quickly became part of our tradition. A few years later, my mother was pregnant with me, and a few hours after she ate a hearty serving of this turkey and stuffing, I was born.

When I took a bite of that roti, its mix of aloo and curry was a trip back to my childhood dinner table, a window into whatever lessons in cooking my parents took with them from Bihar to California. It was a roti parcel. It was a weeknight dinner in the Bay Area. The result was a memory forever on the move, a taste always familiar and different: a meal of a global journey, a recipe of a new home.

Nishant Batsha