November 19, 2018

Cambridge, Massachusetts

My coffee turned out thick, almost too sour to drink, but letting it brew so long gave me time to click through seven or eight medical school applications, just to make sure nothing had changed. I am waiting for any movement between “complete,” “invited to interview,” “rejected,”or “accepted.” If I didn’t check I would feel unsettled all day.

One essential component of a successful medical school application is exposure to clinical medicine; real experience, working somewhere close enough to smell patients. In my case, this is scribing in the Department of Urology, perhaps the lowliest job in any wealthy clinic.

Cars were gridlocked today in the spaces between unremarkable office buildings of labs, hospital administration, and clinics. People in scrubs or suits clutched their coffees and wove in and out of the doors.

I was the second person to lock my bike to the rack. I ducked into the restroom, peeled off my leggings and shimmied into business casual.

Pushing a laptop on a rolling cart, I trailed behind a doctor who specializes in men’s health. The hours are long and I spend most of the day standing, almost invisible, in exam rooms. I’ve learned more about physiological changes in the aging male body than any 24-year-old woman is entitled to know.

A tall dad came in, eight weeks after his vasectomy, to confirm that he is in fact sterile. I added a few lines to his chart: date of vasectomy; reports no residual pain; date of semen analysis; screen shot of same, confirming zero sperm.

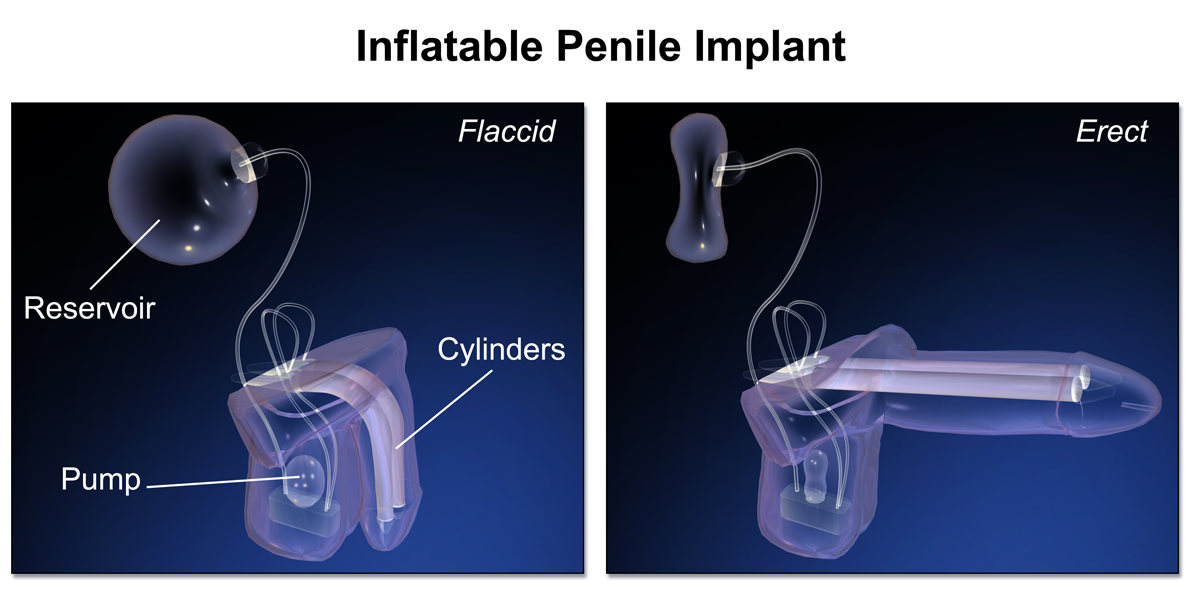

Another patient has tried every medical therapy for erectile dysfunction: Levitra and Viagra and Cialis, mixes of liquid medications he injected at the base of his penis, to no avail. He seems frustrated; I documented this. His only remaining option is surgery. That is, a penile implant: two inflatable pipes laid inside the penis and a pump placed in the scrotum. Squeezing the pump transfers sterile fluid from an abdominal reservoir into the pipes, facilitating erections on demand. Pushing the release button transfers the fluid back into the reservoir, mimicking the flaccid state. The procedure is covered by most insurance.

The doctor left the room to fetch the model. I wondered why he doesn’t carry it with him, tucked into his jacket pocket, since several times a day he needs to pause to fetch this device.

It was in this moment of anticipating the model that the patient’s first wave of questions came. How long does the surgery take? And the recovery? Will I still be able to go to Florida? And then, “You’ve probably never seen someone in my situation before. I’m sorry you have to listen to this.”

An hour and a half or two hours for the surgery, 30 minutes for anesthesia, so just under three hours total. Stay in the hospital overnight, and as soon as he pees the next morning his wife can drive him home. It will be about four weeks until the skin sutures dissolve. There will be a turning point about five days in when he can switch from oxycodone to ibuprofen, and 20 days after the surgery he won’t even need ibuprofen.

But as a scribe I am not allowed to communicate medical information to patients. I let him know he is the third or fourth person in the penile implant process I’ve documented today, and that there’s no reason to be shy or embarrassed.

He was unsure if he was ready for surgery, but he was also only one of 40 patients that day. The doctor cut him off.

No break for lunch, so I tried to stuff a few bites into my mouth. The doctor only consumes fun-size Kit-Kat bars and breakroom coffee, and while it’s frightening to think that this is the fuel of surgeons, I know I could make this my diet.

We rolled into the next room 47 minutes and five patients behind schedule. This was a follow-up on a patient with Peyronie’s disease, a condition where scar tissue forms and bends the penis—in extreme cases, into a right angle. The patient dug into his briefcase and pulled out an envelope of 4×6 photos, lining them up on the desk, an evolution of curves. Per scribe protocol l stood behind a curtain during physical exams, but there really aren’t any guidelines for where to go or stand when the penis pictures come out. I averted my eyes as I entered the doctor’s remarks about each photo into the chart.

As they rehashed options for straightening out the penis—injections vs. surgery—I thought about what to eat when I get home. I used to make elaborate lentil dishes, stews, pastas full of vegetables with homemade pesto. Since the medical school application season started, I’ve been cooking either egg sandwiches, or bean quesadillas, the refried beans scooped directly from the can. I bought a bag of kale to incorporate some fiber.

By the time I biked home it was dark. I clicked through a few applications, again noting no changes, and squeezed in an episode of Mad Men.