Using white plastic chairs and folding tables, the session organizers had arranged the room to designate different areas for “know your rights” training, legal intake, and paperwork documentation. But these divisions didn’t hold, and ad hoc groups formed into huddles of conversation wherever there was space. There was a constant low hum of chatter in the room, but no loud noises; these conversations were the kind one speaks in low voices, focusing on facts and dancing around the backstories the questions implied: Why did you leave your home? (What happened to you there?) How did you get here? (What happened to you on your journey here?) Who in your family is with you? (Who in your family did you have to leave behind?)

Boxes upon boxes of clothing and other donated supplies were neatly stacked along the wall where I had planted myself. I had proclaimed it a “Kid’s Corner” and neatly stacked on one of the folding tables coloring books and notepads, boxes of crayons and color pencils, and a stack of mini play-doh packs, along with a hodge-podge of toys I’d salvaged from nearby boxes.

I arranged and re-arranged the materials and waited for the children to arrive.

My friend Priscilla and I had taken the day off work, driving from Orange County to Tijuana to volunteer with groups doing assistance work with migrant families camped out on the border seeking asylum. Priscilla had filled her minivan with a half-dozen tents, sleeping bags, and boxes of diapers, and we arrived just in time to join the volunteer orientation that took place each morning at 10 a.m.

Though we had driven about a hundred miles to be there for the day, others had traveled from all over the country: there was a group from Florida, another from Pennsylvania, two lawyer friends from Seattle, and several students from the Bay Area. Most were staying for a week or more. Many were lawyers, several were immigration lawyers, but the most valuable among us were the handful of immigration lawyers who spoke Spanish.

The organizers—who had up-ended their lives to assist with the crisis—reminded us that the situation at the border was, in and of itself, nothing new. There have always been individuals and families crossing the southern border seeking asylum in the United States, they explained; we have always turned many of them away.

What was unique, today, was that asylum seekers at San Ysidro and other official border crossings were not being given the chance to apply for asylum, arguably in violation of international law. Instead, for months, the Trump administration had been putting absurdly low limits on the number of asylum seekers who were allowed to enter the United States each day, a practice it calls “metering.” As a result, those who had traveled to the border fleeing violence—sometimes over thousands of miles—were waylaid indefinitely, here, at what was supposed to have been the safe haven at the end of their journey.

Gaining asylum in the United States has never been a cakewalk. All asylum seekers are assessed on the credibility of their claim; they must convince a judge that, in the parlance of immigration law, they have “a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion” in their own country, and unable to safely return. Those found not to have a credible asylum claim—who are deemed insufficiently fearful—will be returned to their countries of origin. The rate of success varies widely by country of origin: for some countries it is close to 75-80%, but for asylum seekers from El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala, the figure is closer to 20-25%. Today, these figures may be even lower.

But as inhumane as the growing crisis is, immigration to the United States has always been cruel. For would-be immigrants who are poor or who are from poor countries, we are a veritable fortress. Your chances of being granted asylum are substantially improved if you have legal representation, which not all asylum seekers do. Without being wealthy, without a visa for school or work, or without winning a literal visa lottery, it’s very difficult to come unless your life is in danger. But even those traditional asylum categories are being eroded; in June, then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions declared that those fleeing domestic abuse and gang violence will generally no longer qualify for asylum.

As I type these words, some tens of thousands of families in makeshift shelters, some sleeping on the street, have been waiting for months for the opportunity simply to present themselves and their stories to American immigration authorities, an opportunity which they may now never have.

I am a lawyer, but I am not an immigration lawyer; I am, however, a mother of three. So when the organizers divided us into teams, I volunteered to set up a makeshift kid’s table. As the families came into the room, and as their parents paired off with lawyers and interpreters, children gathered at the table, around it, and under it. I passed out coloring books, notepads, and crayons; I struggled to separate two small brothers squabbling over toys and art supplies, and to keep the younger of the two from eating the play-doh when my back was turned.

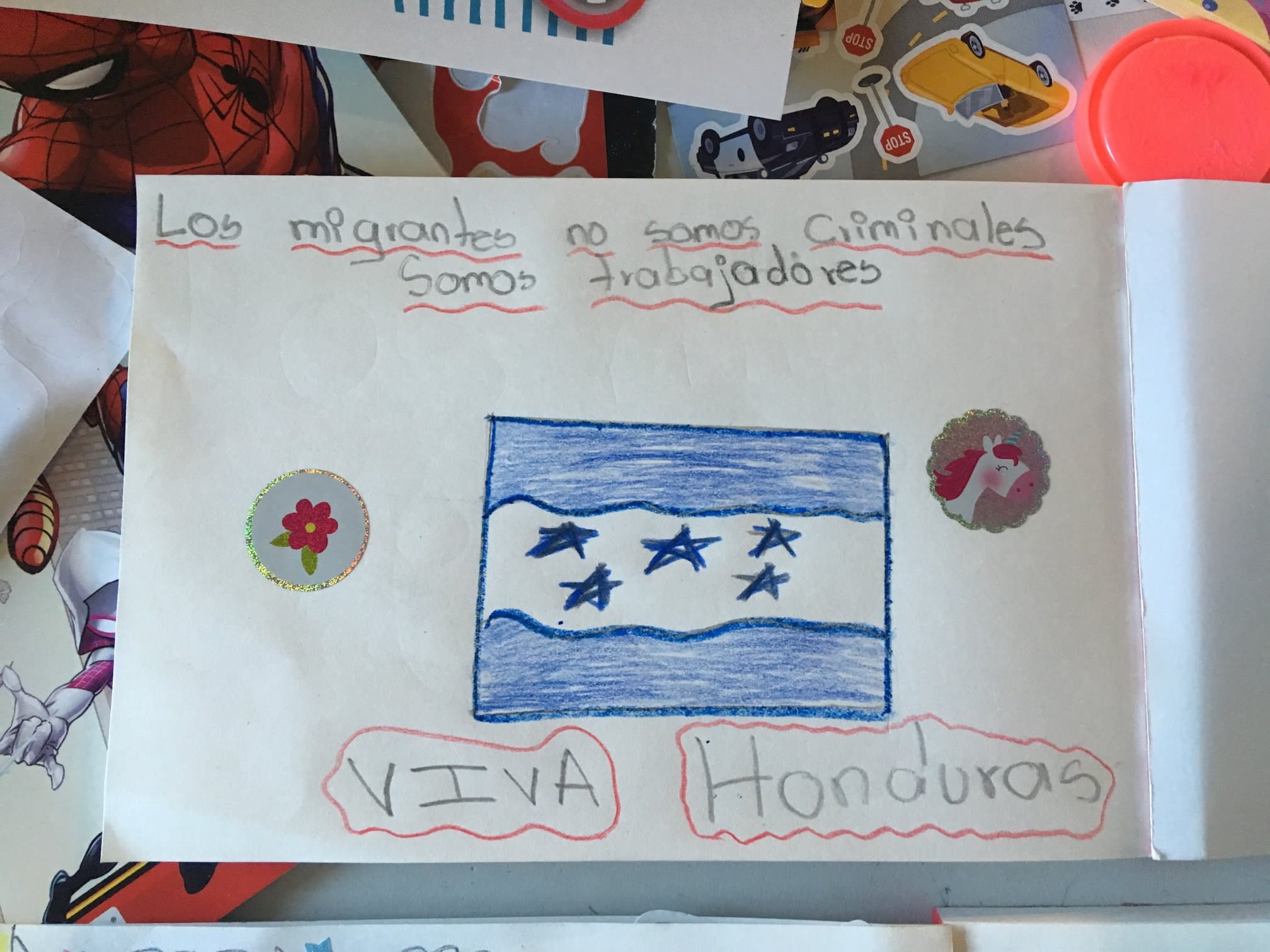

The older children tended to be more shy, but they also came for notepads and color pencils. But all the children would pause when they’d finished coloring or drawing to show me their work for my approval. One girl that looked between 10 and 14 drew a picture of the Honduran flag, bringing it to me with a slight smile and holding my gaze as she showed me her work.

I told her it was beautiful, and true. I thanked her for showing it to me, and asked if I could take a picture with my phone.

Picture drawn by a young girl I met in Tijuana.

At some point in the day, pizzas were delivered. The adults were too distracted to eat, but the children were hungry so I distributed slices of cheese and pepperoni as best I could. With no plates, we made do with napkins and our hands; when the pizza ran out and some children asked for a second slice, I had to tell them there was no more left.

In the afternoon, Priscilla and I went to Costco to buy supplies; we’d collected about a thousand dollars from friends and coworkers, but with the help of a currency converter app on my smartphone, we learned that Costco prices in Tijuana are basically the same as the California Costco. We’d been told that Costco pizza in Mexico is better than in the U.S., however, so we each had a slice. We couldn’t tell the difference. Apparently all Costco pizza is just good. After we loaded Priscilla’s car up with snacks, blankets, and clothing supplies, we bought three large Costco pizzas to bring back.

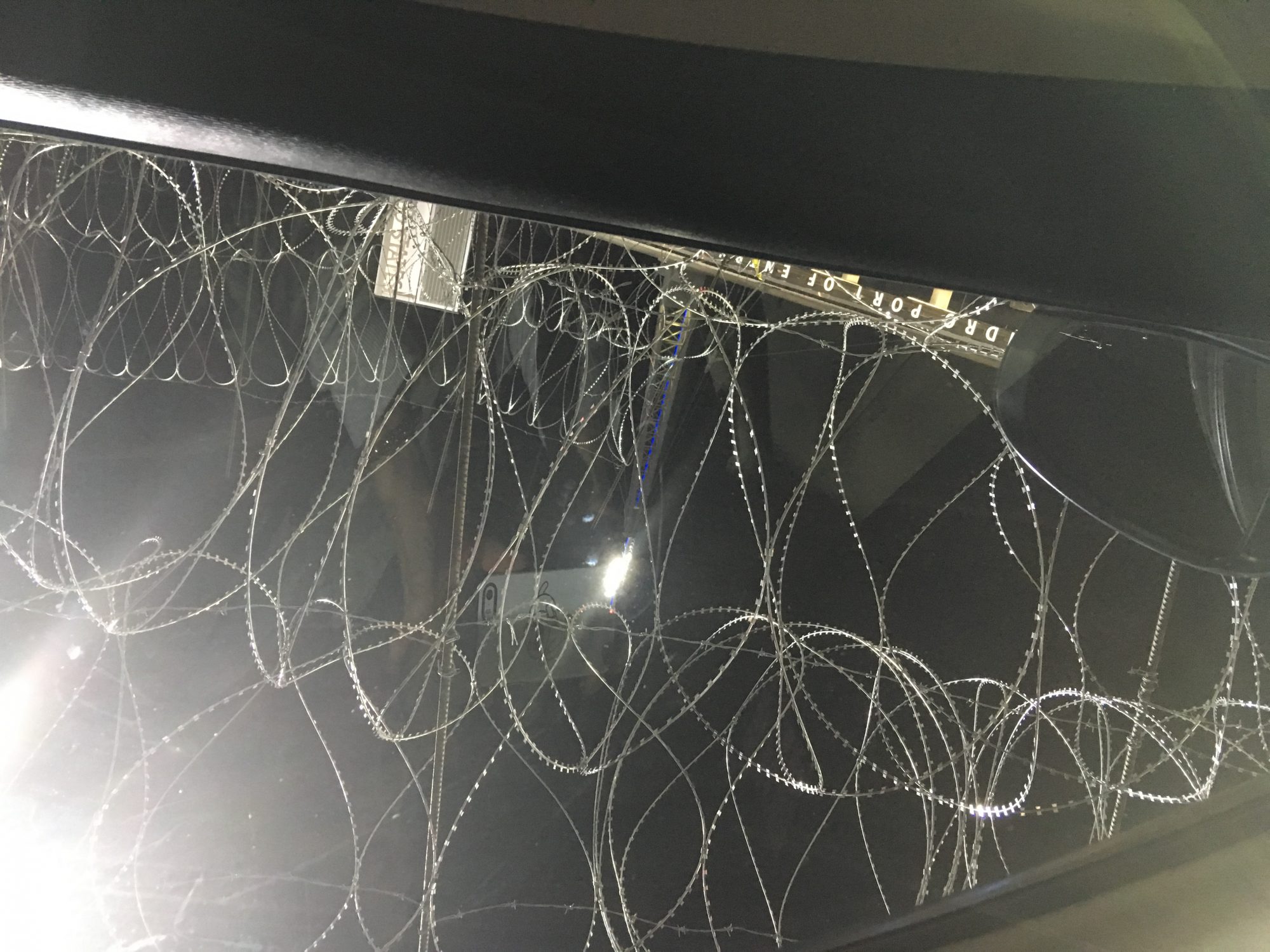

It took us three hours that evening to cross back, perhaps half a mile from Tijuana to San Diego, across one of the most militarized borders on the planet. As the sky grew darker—and as an enterprising community of small business owners selling churros, coffee, and tourist tchotchkes swarmed around us—it felt like we hadn’t moved in ages.

But at last, we saw the bright lights of the San Ysidro Port of Entry looming before us. On either side of the road, and in some places in the center, there were coils upon coils of barbed wire, endless repeating loops of tiny knives, a grim reminder of where we were, and who we were, and what that meant. If it took the two of us three hours to inch our car across the border, it was because those knives and razors and wire were not for us. It would take weeks for the families we’d spent the day with to cross that border, or it would take months, or perhaps they would never cross it at all.

We were told that each day, fewer than 40 asylum seekers are allowed across the border, a drastic decrease. On Tuesday, Trump addressed the nation, trying to justify the need for a border wall by citing the growing crisis on the border. There is a crisis, and it’s growing. But it’s a humanitarian crisis, not a security crisis, and it’s entirely of his making. And as the government shutdown heads into its third week, thousands of families are waiting across the border in Tijuana, including that young girl who drew the picture.

Volunteers are still needed who can travel to Tijuana in the coming weeks. For more information, please contact Al Otro Lado or the National Lawyers Guild, Los Angeles Chapter. If you are not able to volunteer in Tijuana but still want to help, please consider donating to World Central Kitchen, which has a feeding operation serving hot meals in the shelters in Tijuana, or to Alliance San Diego, which has a travel fund to assist families with children who been allowed to enter the United States.

Amy Chen