When Ghana’s oldest football club, Accra Hearts of Oak, issued the prospectus for its initial public shares offering in 2011, the cover image featured a 1969 photo of George Alhassan, captain of the Hearts, and Pelé, the most famous footballer across the Black diaspora. Alhassan stood on Pelé’s right, draping a Kente stole around the latter’s neck. Pelé held a copy of The Saga of Accra Hearts of Oak Sporting Club, a recent history of Alhassan’s club.

A photo of two black footballers, one from Ghana and the other from Brazil, was politically significant. When Ghana gained political independence in 1957, the first country south of the Sahara to do so, many black diasporans moved there to live and work, including W.E.B. Du Bois and Maryse Condé. By 1966, when Kwame Nkrumah, Ghana’s first president and a pan-Africanist, had been deposed in a largely bloodless coup d’état, many of the diasporans had already left the country, having fallen out with Nkrumah; others followed after Nkrumah was overthrown. Welcoming Pelé with a Kente stole, a symbol of black pride, signaled that Ghana was still opened to the diasporans. Alhassan was the face of this reconciliation.

I knew about Alhassan the football legend, but Accra-based photographer Francis Kokoroko of Nuku Studio introduced me to Alhassan the photographer. Kokoroko showed me some stunning Alhassan photos featuring J.J. Rawlings, Ghana’s ruler from 1981 to 1992 as a military leader and from 1992 to 2000 as a civilian president. In one photo, Rawlings was on horseback, cigarette in his mouth, dressed in military uniform. In another, flanked by his aides, he stood on a van and addressed a large crowd. Intrigued, I wanted to know more about Alhassan’s career as a photographer, so I went looking.

Situated in the bustle of Accra, the headquarters of the Information Services Department (I.S.D) is nested within the Teachers Hall Complex to the north, the University of Ghana city campus to the south, and the Greater Accra regional coordinating council to the west. It’s an unassuming building, banal and bureaucratic. It is where Alhassan worked.

In the hallway of the ground floor, a set of louvre blades lends a view into the offices. A middle-aged man listens to a radio set and dozes off, a woman behind her desk taps at her phone like every tap is a promised blessing, and a man photographs the files in the offices, led by a fellow in a two-piece blue-black suit.

From the main door, I walk through the hallway to the last room on my left, the photo library. When I ask Librarian Solomon Amarteifio about Alhassan’s photos, he seems momentarily lost. His eyes wander. Then he trains them at me and shouts, “Gã Mantse!”

Gã Mantse is a traditional chieftaincy title for the King of Gã, the major ethnic group that inhabits Accra. But Alhassan was neither a king nor a Gã. He earned the nickname while playing as a forward for the Accra Hearts of Oak, the team he captained while wearing the iconic number ten jersey. I wanted to find out about Alhassan the photographer, but that meant reckoning with Alhassan the football star.

Born in Tamale, the capital of Northern Region, Alhassan became a football force after the reigning star, Edward Aggrey-Fynn, left to join Nkrumah’s Real Republicans after the 1961/1962 season. It’s unclear when he joined the Hearts, but by 1969 Alhassan was captaining the team. Simultaneously, he was building a career as a photographer. Whereas football put him in front of crowds and cameras, photography allowed him to observe and record. He had the rare opportunity to enter the historical record as a subject and historian. He died in 2013 at the age of 72.

The 1968-1969 football season was perhaps the most productive in Alhassan’s career. He was Hearts’ top scorer with twenty four goals, and was memorialized in Stephen Borquaye’s 1968 book, The Saga of Accra Hearts of Oak Sporting Club, as a “fearless center forward who has no respect for any defense.” Ken Bediako, the football writer, on the other hand, called Alhassan an “opportunist goal soccer” in 1969. Alhassan also played international friendlies against Berlina Club in December 1968 and Athelect in September 1969. The two matches were both played at the Accra Sports Stadium.

Perhaps Alhassan’s most famous goal was one that did not stand. On 6 February 1969, Pelé-led Santos FC from Brazil played an international friendly match with Accra Hearts of Oak at the Accra Sports Stadium. Santos was holding Hearts to a 2-2 draw when Alhassan scored the third goal—it was disallowed. Ken Bediako writing for the Daily Graphic newspaper the following day reported, “George Alhassan actually put the ball in the net in the 67th minute but linesman Hulede who was fast becoming flag happy, ruled it offside.” Alhassan was denied a piece of history. But the match inspired a string of Hearts’ successes in the 1970s: they dominated the local scene and won the local league for the first time in eight years.

Following the success of the Santos match, Hearts embarked on a United Kingdom tour in August 1970, playing seven games including against Charlton Alethic, Southend, Barnsley, and Swansea City.

Juju stories abound in Ghana’s football lore, and Alhassan was folded into this tradition. Prior to a 1970 league game against arch-rival Kumasi Asante Kotoko, the defending league champions, oracles had proclaimed that a Hearts player had to be injured for the team to win the match. The match was to be played in Kumasi, Kotoko’s home ground. In the third minute of the match, Kotoko defender Oliver Acquah tackled and broke Alhassan’s leg. Hearts won the match by holding on to the first minute sensational scissor kick goal by Robert ‘Bobby Charlton’ Foley.

Juju might have been at work, but as E.A Boateng later wrote for the Daily Graphic, “throughout the game, Hearts played a masterpiece of soccer and excelled both in strategy and skills.” Heart went on to narrowly lose the league title to city rival Accra Great Olympics. The following years were bright for Hearts but not for Alhassan. The Acquah tackle was the beginning of the end of Alhassan’s career as a footballer. By the end of the 1972/73 season, he had faded from prominence.

If, in his football life, Alhasan was the face of the nation and internationalism, in his photography life, he was an observer of the ordinary. Many of his photographs focused on development in northern Ghana, the region he called home. The British believed that those of northern ethnicities were physically stronger than the southerners. As such, during colonial rule, they turned the area into a labour pool for the military and construction work. Additionally, they intentionally curtailed western education to avoid the resistance they had faced from educated southerners. Infrastructure like rail lines was never extended to the north. So even at political independence,the north was not ready for a life of its own.

The earliest Alhassan photo that I have seen was taken in Accra four months after the Nkrumah coup in 1966. The photo was featured in a series on transportation in Ghana. In the photo, four women climbed a Bedford tro-tro—named after the colonial penny (tro) fare charged for the ride. The truck was fitted with a wooden frame where the passengers sat. Two other women readied themselves for a climb. Another with a tray on the head, probably a hawker, stood. Two men were in view. One with the back facing the camera and the other, half-bodied, faced the view of the camera. The back-to-camera man was hailing patrons. He was either a mate—a truck conductor—or the driver of the truck. In the horizon, branches of trees found a home in the skies.

It is probably unsurprising that Alhassan, who found fame after he traveled from the north to the south, focused on travel and mobility. After all, it was his own travel that integrated him into Ghana’s vision of itself. Far from representing an unchanging past, a role often ascribed to women, the women in the tro-tro embraced mobility and the independence it promised.

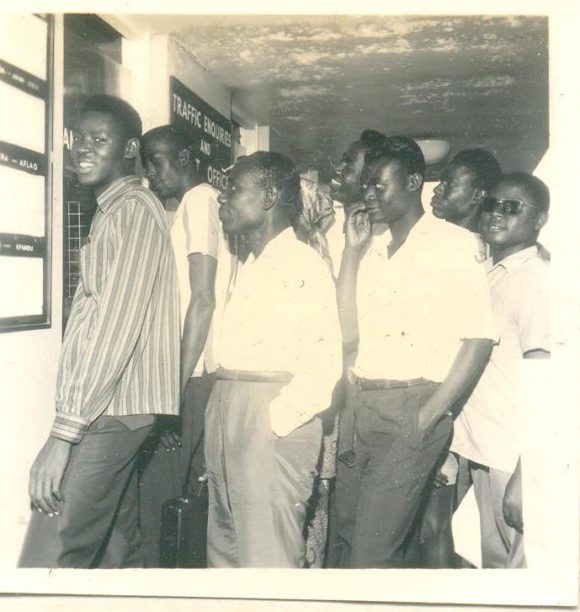

Alhasssan also covered the inauguration of the State Transport Cooperation in May, 1968, extending his early interest in mobility. The event took place in Tamale. In one of the photos from the event, a group of people queued in front of a ticketing area. Unlike the photo from Accra, some of the subjects noticed Alhassan and looked in his direction. It seemed some were posing for the photo while others looked forward. Did those who looked toward the camera recognize Alhassan as one of their own? Did they imagine that the tickets they acquired would similarly embed them within a national imaginary?

Official state photographs participate in national mythmaking. They show development and regional integration, claiming to demonstrate that the state has fulfilled its promises. From this distance, it’s difficult to know if Alhassan understood himself as a state mythmaker, on and off the football field.

In 1976, Alhassan took photos of Tamale for the department’s Ghana’s main town and cities series. Mainly, the photos focused on the market and housing. As with the earlier photographs, these ones demonstrated development, a Ghanaian modernity that was part of the state’s mythmaking.

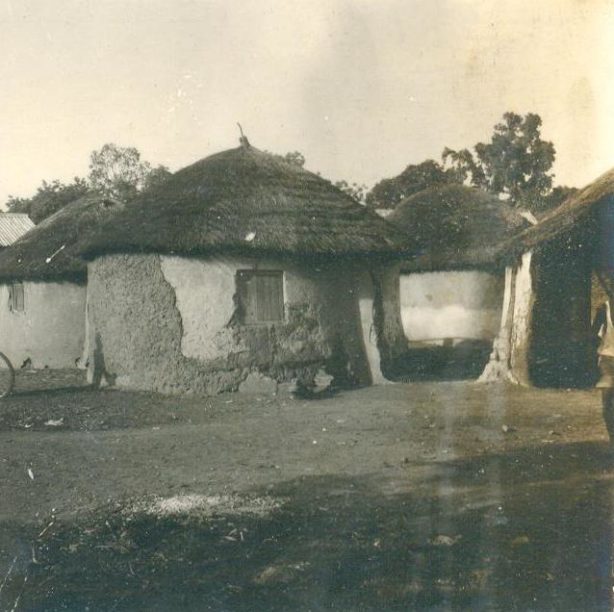

One of the photos is a close-up shot of huts. It is captioned “these old mud houses are gradually being replaced by modern houses.” It seems there was an attempt to avoid the presence of humans in the photos, probably to indicate that the past represented by the huts had been abandoned. But if you glance closely, you can see a half-bodied young man to the right, and, to the left, a bicycle wheel and a shadow cast on the hut. The bicycle wheel close to the hut indicates that the past and present can co-exist, that those who ride bicycles and are mobile can live in huts, refusing a story that the turn to the future requires abandoning the past.

The “modern houses,” on the other hand, were made in long shots. The estate houses that were captured by Alhassan were being built by the government of Ghana.

These shots manipulate our gaze. We are fixated on the huts while the modern houses free our eyes. In the right near-top corner of the huts, roofing sheets could be seen. Could it be that the close-up shot was to hide them? Did the photo posit that development is largely the agency of the government? In these photos, Alhassan seemed to present modernity as an antithesis of tradition and a shift from the colonial to the postcolony.

Perhaps what is most striking about the housing photographs is how empty they are. With the exception of the partial shadow on the huts and the partial body, no other humans can be seen in either photo. If they represent tradition and modernity, they represent them as abstractions, devoid of human action and interaction.

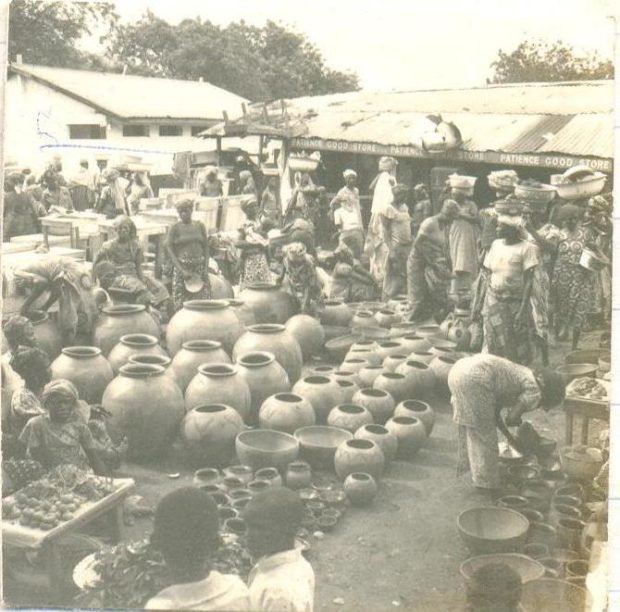

Whereas the pictures of huts and homes lack human occupants, the market scenes are bursting with life. Women traders perform care work and commercial work, as they carry their children on their backs. And in the scenes of standing and bending over and looking, it’s easy to imagine the range of commercial and interpersonal interactions taking place, not only the exchange of money for goods, but of gossip and rumor, care and conflict.

Whereas the outside of the market seemed to cultivate more interactions across gendered lines, the inside of the market appears more highly gendered. The market scenes seemed chaotic. But really they were highly organized. There was a footpath that ran through the market. There were different sections for different wares. By the street side, unlike the inside of the market, both women and men inspected the wares that have been displayed for sale.

Yet, I think it would be a mistake to think of outside and inside as distinct spaces. The interactions outside traveled inside, just as those inside traveled outside. No doubt news and gossip moved in multiple directions, and the relationships forged in one space influenced those experienced in another. But photographs hold their secrets and their silences, and the best we can do is imagine into the worlds they represent.

The northern part of Ghana is chronically undeveloped. Alhassan’s work was an important photographic witness to even the meagre postcolonial attempt at development. He, unlike the Basel mission photographers and the colonial officers, would not see his subjects as exotic artefacts who needed saviours as he was a native.

Alhassan, in front of and behind the camera, contributed to the Ghana project. He served both civilian and military governments diligently, as the face of national and diaspora reconciliation on the football field and as a seemingly apolitical bureaucrat off the field. But perhaps his most important legacy is as a son of the north who conquered national and global hearts.

Kwabena Agyare Yeboah