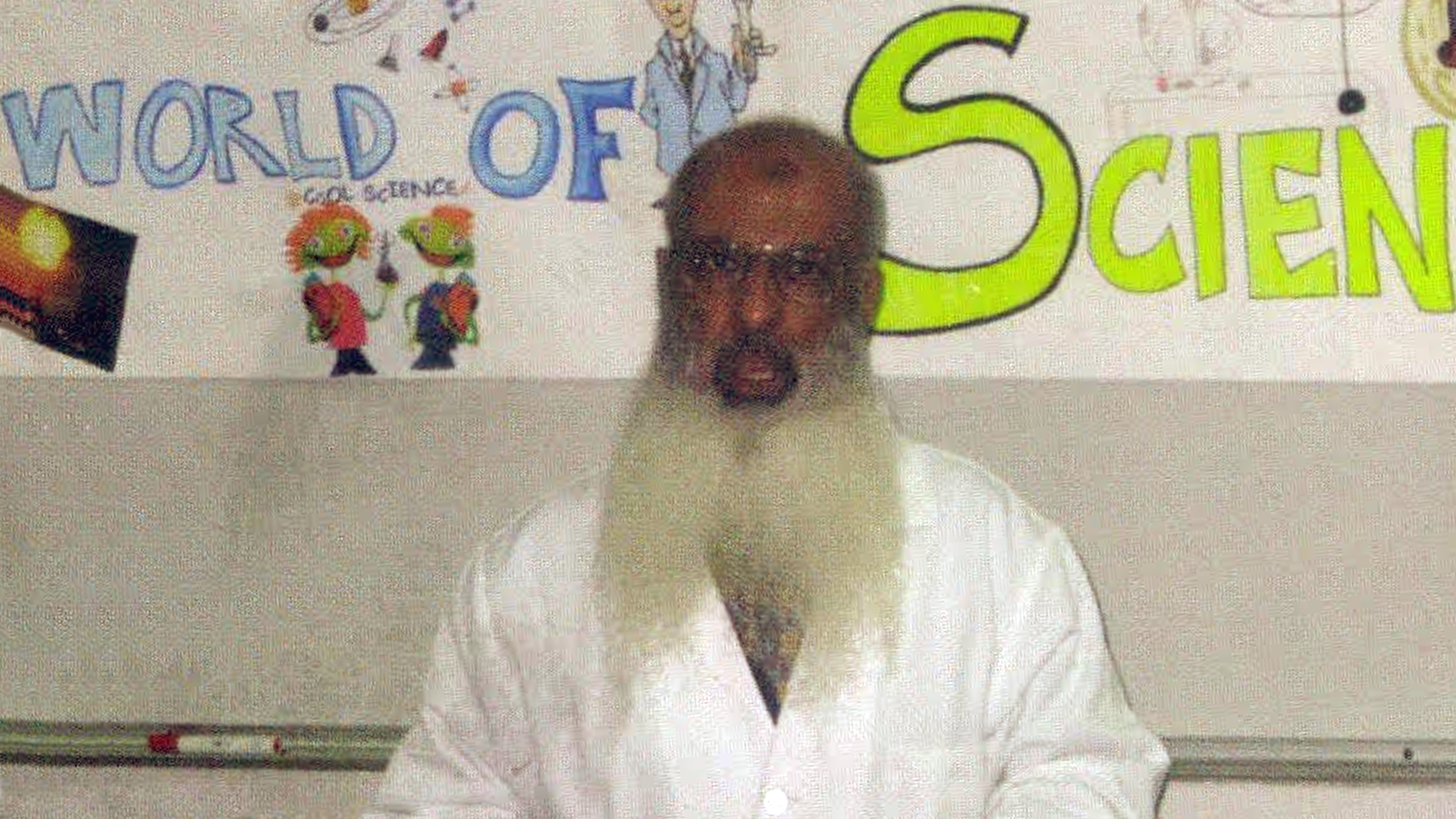

Some months before Mohammed Bouazizi’s December 2010 self-immolation lit the spark of the Tunisian Revolution a balding high school chemistry teacher with an unkempt grey beard demonstrated the explosive reaction between red phosphorus and potassium chlorate in a classroom in Tunis.

Dr. Syed Ali was giddy while rushing through his explanation on that final class of the school day. I remember being anxious, along with all the other smokers in the class, to get out of there and have a cigarette. Our teacher had talked up the experiment throughout the entire class period. It would produce an explosion loud enough, he said, “to separate the boys from the men.”

After mixing the compounds, we witnessed a brief, lackluster flash followed by a pathetic boom—more like a loud fart. Dr. Ali was dejected, and stayed that way for the rest of the class.

Ours was an “international school,” right across the street from the American embassy. We held an annual International Day where all the different nationalities paraded through the school grounds, more than 60 flags waving behind their respective delegations. But during the Revolution, students were told to stay home and, in case the situation grew more violent, to prepare for classes to be conducted online.

In January 2011, after weeks of protests, the dictator Zine El Abidine Ben Ali fled to Saudi Arabia, in the tradition of other Muslim dictators like Uganda’s Idi Amin and Pakistan’s Nawaz Sharif. Students and parents were informed that it was safe to resume classes at our school, the American Cooperative School of Tunis (ACST), which I attended from 2004-2011.

We were to return to normal, but this proved difficult.

We had not only seen Ben Ali toppled; the majority of the school had also watched Phil Rees’ interview with “Abu Muhammed” in Britain Under Attack. He talked about the supposed war between Muslims and non-Muslims. We immediately identified this man as Dr. Ali. We heard his characteristic rushed speech; we saw, beneath the afghan wrapped around his head, his unmistakable golden glasses.

Dr. Ali had been apprehended on school grounds. Our homeroom teachers told us that during the Revolution, the CIA, who had apparently been keeping tabs on him for some time, had warned the school about Dr. Ali’s posts on an al-Qaeda-affiliated message board. These posts detailed the weak points in ACST’s security. He was thought to have been hoping to attack our school in the bedlam of the Revolution. Dr. Ali had taught in an international school in Germany before coming to ACST, we were told.

Our teachers sounded worried, but we were stifling chuckles because this would-be menace had not bothered to change his signature glasses for his pseudonymous appearance in a documentary film.

Ali was Egyptian, but held American nationality. He was short and squat. One student commented that he was perfectly bell-shaped. He wore only cargo pants. Though no one said it, out of respect for his PhD (which might have been fake, for all we know), he was a horrid teacher. He was frequently mistaken about the subject material, answered questions incomprehensibly, and was rarely prepared for experiments. His replacement was shocked at how little my class had learnt the previous year, and at how many explosive compounds Dr. Ali had kept in the chemistry stockroom.

We knew that Dr. Ali was a religious fundamentalist, because he refused to attend parties in houses that contained alcohol. His wife, whom I only ever saw once at a Thanksgiving dinner held by another American-Muslim teacher, was not allowed to greet a man without her husband’s permission. Before the Islamist rise in post-Revolutionary Tunisia, she was the only woman in Tunis I had seen wear a full-body, black abaya.

Ali was one of the few Muslim teachers at the school. My mother, who taught in the elementary school computer lab, was another. He would offer her a cheery “assalamu alaikum” now and then, but refused to attend her iftar dinners during Ramadan. She still maintains that these rebuffs were indications that he should never have been trusted.

He was fond of the Muslim students, especially the Arab ones; this was rare at my school, because Arabs, who made up the bulk of the non-teaching staff, were looked down on.

Once, in a math class, we got to talking about how, because of the Revolution, we might not be able to finish the International Baccalaureate Diploma programme in which most of us were enrolled. The lazier students, such as myself, wondered whether the programme might not just pass us all out of pity. A classmate was against this because it would entail passing a certain Arab student who had evident learning disabilities. She hated the idea of “someone like him” attaining the same degree as hers. Our teacher only chuckled.

Dr. Ali, on the other hand, was especially fond of bullying my Ethiopian friend, with whom I smoked cigarettes nearly every day behind the school, after the final bell rang.

Once this friend and I submitted separate lab worksheets to Dr. Ali. We had worked on them together, so our papers were practically the same. With the name Muhammad—the most Muslim name there is—I received an A. My friend, the Ethiopian Orthodox Christian, received a D.

This friend carried a worn passport-photo size icon of Mary in his wallet. “For protection,” he said. It did not protect him from Dr. Ali’s anti-Christian anger. Dr. Ali would bark at him, always with a smile spread across his lips, for any misstep. Heaven forbid my friend needed to borrow a pen from another student.

Dr. Ali would also glare whenever the non-Muslim lab assistant, whose manner of dress he disagreed with, entered the classroom. He pushed for her to be fired, I learnt from my mother. She was eventually replaced by an Arab-Tunisian woman, who dressed more to his liking.

We joked that my Ethiopian friend must have been caught kissing one of his four daughters because of Dr. Ali’s irrational hatred of him. In fact his daughters were never seen at the school nor, as far as we knew, did they leave his house. We only knew of their existence because some of our teachers, who lived in his neighborhood, told us about them.

We joked about how Dr. Ali fit the image of a stereotypical terrorist, considering his radical approach to Islam, his long, scraggly beard, and the fact that he boasted of a having a pilot’s license. Years later, in America, when I told a college friend about Dr. Ali, she burst out laughing because the Bond villain, Dr. No, came to mind.

Screenshot: 'Britain Under Attack"/Vimeo

Screenshot: 'Britain Under Attack"/VimeoMy mother does not laugh at Dr. Ali as easily as I do. During the rest of her tenure at the school, she would walk home in zigzag patterns, in case Dr. Ali was also a trained marksman. She thanks God that he never joined us for iftar because she fears that he might have used the occasion to attack us. These dinners were full-blown parties where myriad people, believers and non-believers, gathered.

I realise now he did not join us because—more than the West, more than America—Dr. Ali hated multiculturalism. Even the clumsy, superficial multiculturalism of my school that tolerated his retrograde views. Why else would he consistently target international schools?

I suspect that he hated Muslims like my mother, who were proud of my school’s diversity. She, who has worn a hijab since we moved to Tunisia, having left her abaya behind in Saudi Arabia. She, who wowed that same Ethiopian friend Dr. Ali bullied by speaking to him in Amharic.

My school’s administration, with a tinge of embarrassment, amped up our security after Dr. Ali was found out. They installed more metal detectors at the entrances, hired more guards wielding AK-47s, and increased the number of safety drills —wherein we would huddle up in the main gym, in neat rows—to every few months.

All that extra security proved to be for naught when, a year after the revolution, in response to the Islamophobic film Innocence of Muslims, a mob of looters attacked ACST. During my first semester at college, on the 14th of September, I watched videos of the elementary library and my mother’s computer lab burning down. No one was harmed as the administration had chosen to close the school early that day after the embassy had been attacked.

It was only then that I was terrified. During the Revolution, I had been struck by the wavelike power of the mob to change nations. Though I did not participate in any of the protests, I watched people, most only a few years older than myself, take back their nation from a dictator.

After Ben Ali’s expulsion, Ennahda, the ruling Islamist party, twisted the spirit of the Revolution and radicalized Tunisia. One consequence was the attack on my school. Ennahda too would step down at the behest of the mob after the 2013 protests, following the assassinations of secular opposition leaders such as Chokri Belaid and Mohamed Brahmi.

Now, in America, I witness the continued radicalization of another mob. America’s Islamophobes vilify all Muslims, wholly ignoring the documented fact that Muslim terrorists disproportionately assail other Muslims. Some of them are the same Muslims that American Islamophobes refuse to accept as immigrants. All because they fear, so they say, that men like Dr. Ali will radicalize Muslims already within the country or attack American institutions.

Having known a terrorist, let me say that I simply do not know how to fear this man. Dr. Ali, for me, has always dispelled the politically expedient myth of the mastermind Muslim terrorist.

He was not an equal enemy to those who hunted him. They knew each of his moves while every action on his part was poorly planned. His inane understanding of Islam appealed to none of the Muslims in my community.

How am I to fear a man terrified of a woman’s clothes? A grown man who bullied a young student because of his faith. Who was caught on a message board, for heaven’s sake.

Every now and then, old classmates will tell me of rumors concerning Dr. Ali. That he is under house arrest in Tunis or that some European country wants him extradited. We joke, as we always have, about Dr. Ali. But we do not speak of the Revolution nor of our school’s immolation. Having seen the mob overthrow a would-be king, burn down a library that housed some religious texts, and fester with hatred for the other, we remain in silent awe and fear.

ML Kejera