When Hurricane Harvey hit in August 2017, I made two calls and sent two emails to the Gulf Coast. After spending a weekend bailing water from my sloped front porch in Austin, I was also flooded with a deluge of images from the southeast corner of the state: roofs torn clean off, canoes floating down abandoned streets, half-submerged cars. As is the impulse when a catastrophe hits, my mind began to wander and I worried about the images I wasn’t seeing.

I called the University of Texas’ Marine Science Institute in Port Aransas for an article I was working on. They were fine, until they weren’t. Everyone was safe, but the animals had to be relocated, a ton of data was lost, and about a week later, the research pier stretching into the Gulf of Mexico collapsed. Fearing a repeat of the 1900 hurricane that annihilated Galveston, I reached out to the proprietor of the Bryan Museum, which boasts the largest collection of Texana in the world. Not a drop of water made it inside the building. Then I called a friend’s half-sister for a freelance project. Her houseboat in Rockport was feared to have been destroyed—she later found out it was. She and her husband fled to Austin from the beachside town in the middle of the night with their five dogs and three cats.

The last inquiry I made was to the general info email address at Screwed Up Records & Tapes, located on the southside of Houston. An hour later, I got a response from an account linked to the name Big Bubb. It read: “Yes the store is safe thank god. No damage. Yes we are open. God is good excuse me god is great. We are so thankful.and thank you for even asking.”

Of course, no one wants the roof to fly off their place of business, but Screwed Up Records & Tapes is not a normal business. It’s a brick-and-mortar record store that sells neither records nor tapes, but rather CDs. These discs are all by a single artist, the late DJ Screw, the inventor of chopped and screwed music, who has been dead almost two decades. If the water decided to make an indoor appearance, and the stock was destroyed, there’s no telling if the shop would ever reopen.

DJ Screw may not be a household name nationwide, but he is in Houston. Texas Monthly executive editor Michael Hall remembers being at a poker game in Austin in the late ’90s when someone at the table told him about kids “slowing music down and drinking cough syrup and driving cars around.” That syrup, often called “drank” and known for its purple hue, contained codeine and promethazine, and had been putting rap producers and listeners in Houston in the mood to lower BPMs by unprecedented margins. A musician himself, Hall’s interest was piqued, but by the time he figured out what the story was, Screw had died. He spent months traveling to Houston and Smithville—where Screw was born and forever rests—for a story in the April 2001 issue of Texas Monthly.

As the years pass, climate change has made natural disasters less of a shock and more of a fact of life for those living on the Gulf Coast of Texas. Like the Marine Science Institute and the Bryan Museum, the cultural history Screwed Up Records & Tapes archives is only preserved as long as the building it sits in survives.

I’d been listening to DJ Screw for more than a decade, but had never visited the shop. For fans like me, it’s a place of legend. After this reminder of its impermanence, I decided to finally make the pilgrimage to southwest Houston.

If you call Screwed Up Records & Tapes between the hours of 1 and 9 p.m., a man will answer, saying in a thick Houston drawl, “Screwed Up,” as a half-question, half-statement. If you call before or after those hours, or on a holiday, you will be greeted by a recording from legendary Houston rapper and Screwed Up Click member E.S.G. “What it do, man, it’s E.S.G., Screwed Up Click representin’,” he says, before reciting the store’s location and hours.

When I emailed the same account that so cheerily responded to me after the hurricane, I was met with silence. When I Facebook messaged the store, I was informed that only Big Bubb, the shop steward and Screw’s cousin, could help me. If I wanted to interview anyone at the shop, Bubb was the gatekeeper.

I spent two weeks calling the shop looking for Big Bubb and getting little more than a “nah” in response. I heard the (entirely charming) answering machine message so many times I was dreaming about it. I finally reached my intended target one afternoon. I asked him to carve out a small chunk of time in the next few weeks for me to visit him in Houston, perhaps breaking a journalistic barrier along the way as I breathlessly spit out bromides about Screw’s ongoing legacy and the shop’s importance.

He turned me down. Requests for interviews also went ignored by E.S.G. himself and DJ Red, billed as the “mixtape deejay for Screwed Up Records.”

This was maybe the first time in my decade-plus of reporting that someone in the business of selling a product not only didn’t drop everything to talk, but flatly refused an opportunity to peddle their wares. In the first few minutes after I told Bubb that I understood his decision, I took it personally, as reporters sometimes do. Did I bug him too much? A few days earlier, I had gotten paranoid during when the shop stopped answering the phone for five straight calls. Did they know my number by now? Fuck.

But his refusal makes complete sense. Sure, record stores are the Sumatran tiger of the business world, but this is not a normal record store, or even a normal business. It doesn’t need to participate in the economy of awareness. It is quite possibly the only record store left that doesn’t need to worry about attracting customers. Chopped and screwed music became popular in Houston in the early 90s, but hit a point of global awareness in the late 90s with the help of peer-to-peer sites like Napster and Audiogalaxy. Rap fans became aware of an entirely new approach to music whose lack of major-label legitimation made it all the more enthralling, and its audience reached far beyond Houston. But, as I would find out as I dug deeper into the world of Screwed Up Records, it has never tried to be anything other than part of the neighborhood.

U.S. Route 290 approaches Houston from above, passing by billboards for a white, dreadlocked personal-injury lawyer named David Komie (“The Attorney That Rocks!”), the Texas Cotton Gin Museum, the future site for the largest cricket complex in the United States, and more Ted Cruz yard placards than you could count. It’s the kind of mishmash you get used to in a state so at odds with itself across county lines. Then, out of nowhere, downtown Houston hits, and the meandering highways that encircle the city create a dizzying effect that only dissipates as I wind down south. Going further south still, down Hiram Clarke Road, then east on West Fuqua, I pass the Come N Go that UGK shouts out on “One Day” from their classic album Ridin’ Dirty. I’m in a different city entirely, it seems.

I almost miss it driving by, the red building with yellow stripes and a white awning, that also houses M&C Tire Shop. As I walk up to the door, I see a man pulling on it. “They closed?” he says, peering into the front window. I have a moment of panic when I think I’ve not only blown my chance to interview the proprietor, but also arrived on some sort of holiday. To my relief, within a few minutes, a large man in sweats apologizes and unlocks the door. He lights a cigarette, waves us in, and tells us to pick out what we want from the whiteboards that read “SCREWTHOUSAND 18!” above a list of 300-plus titles.

This is perhaps the only record store in existence where no albums appear on the floor. You order one off the menu, by name or catalog number, and Big A slides back behind the glass and grabs it for you. You cannot take communion until you have cash—only cash—in hand. I start scanning the whiteboard, but my eyes glaze over. I want so many of them that I start to think that I will leave with nothing.

I try to wander around the store to kill some time and think, but there’s really not much to see. There are two murals: one of Screw himself, and one bearing the name of the store, with splashes of purple paint emanating from a codeine bottle and a Styrofoam cup. There are a few T-shirts for sale, none of which I am real enough to own, much less wear. That’s about it.

Besides my friend from outside, there’s a hip white couple, she with a sweatshirt tied around her waist and he with big, round, tinted sunglasses and a manbun, plus a smattering of other young folks, mostly first-timers. Everyone buys something within the first 10 minutes of being inside the store, while I hug the walls and pray I can make a decision before I’m asked to leave. What’s the point of visiting a shrine without taking an artifact home with me?

You can find plenty of lists that cull the still-expanding catalog of Screw Tapes to a top 10, on websites like Complex, Houston Press, and Passion of the Weiss. Every single one includes some combination of consensus classics Blue 22, Southside Still Holding, June 27, Leanin’ on a Switch, and It’s All Good. These lists have a specific, important utility—cutting an impossibly large catalog down to the essentials. But no list will ever capture the essence of DJ Screw. Like a classical composer, Screw made his tapes for different purposes—a serenade here, a nocturne there. Every tape I have ever heard hits the spot in its own way. Some of them may be better than others, but there are no “bad” Screw tapes, because every single one is composed of rap and R&B classics—even if it’s just the beat, slowed to a crawl.

Ultimately, there are a few different categories of Screw Tapes, and depending on your mood, you might prefer one type over another. There are freestyles, like Ain’t No Sleepin’, straight mixtapes, like Late Night Fuckin’ Yo Bitch, and all-R&B jam-fests, like June 27, with the A-side a mix and the flip perhaps the best example of Houston longform freestyle ever committed to tape.

People have their preferences. I love the freestyles, but I prefer the mixes of classic hip hop and R&B songs, partially because they provide a clear snapshot of the zeitgeist when the tape was made. Late Night, one of my personal favorites, is a compendium of the slow jams that Screw was spinning in 1995, when it was released. It alternates between songs of Screw’s own youth, by Bobby Womack and Teddy Pendergrass, and hits by mid-90s mainstays like Brandy and a not-yet extremely problematic R. Kelly.

As Hilton Als put it in the New Yorker, in an essay about downtown club DJs, there is something personal about the art of mixing records:

Standing bent over turntables, lifting and putting down the silver arms, the d.j.s we knew in the Mike Todd Room, at the Palladium, on Fourteenth Street, and at Hurrah, on the Upper West Side, looked like archeologists digging through popular music in search of themselves. These were the d.j.s we liked best—the ones who were producing their autobiographies through the music they played.

But the mixes that DJ Screw committed to tape were not just autobiographical, though in some sense they were. They were also anthropological histories, spelling out the story of Houston, and, to a larger degree, the American South, during the 1990s.

My foray into DJ Screw came via these mixes, which recontextualized hits I loved as a kid, like UGK’s “One Day” and Tupac’s “Picture Me Rollin’.” These were filtered through Screw’s trademark a narcotic effect, rendering them a curated personal history updated for drug-induced flights of nostalgia during my teens and twenties. When I first discovered Screw, my friends and I had also discovered the trick of pouring codeine syrup, procured for a friend’s bout of strep throat, into cans of PBR. This artisanal cocktail made us want to listen to slower and slower music. The effect was so profound that at one point, a buddy of mine started taking songs that had already been chopped and screwed and importing them into Final Cut Pro to slow them down even more. The time it took to make these preparations was just enough to roll a joint.

The man from Austin who had shown up to Screwed Up Records & Tapes 30 seconds before I did, driving a slick white Mercedes, is a freestyle guy. “See man, this sounds good,” he tells me, of the Screwtape echoing through the store. “I like it. But for me, it’s the freestyles.”

He tries to buy Leanin’ on a Switch, perhaps the most popular pure-freestyle tape (technically a hybrid, if you count the appropriately molasses-like version of D’Angelo’s “Brown Sugar” tacked onto the end). When Big A tells him that they’re out, he is clearly disappointed. He tells me that he used to have one of those old CD booklets filled, four inches thick, with Screw Tapes. But that his car got broken into, and the only treasures the thief took were the music.

Before he leaves with a copy of Blue 22, he mutters to himself, “Damn. No Leanin’ on a Switch? I guess it’s YouTube for me.” DJ Screw’s music is conspicuously absent from streaming services like Spotify, so if you want to listen to a Screw Tape, you can order from the store, hope that the online mixtape archive DatPiff has a download, or listen on YouTube.

It turns out that I have to pull out my phone to check some clickbait-y lists, and decide on Southside Still Holding and Codein Fien. Big A disappears behind the glass and comes back empty-handed. “Sorry man,” he apologizes. “Normally we have all these.” Daunted by the whiteboard in front of me, despite already having 15-20 favorites in my head, I decide on Screwed Up’s long-standing package deal: buy three, get one free.

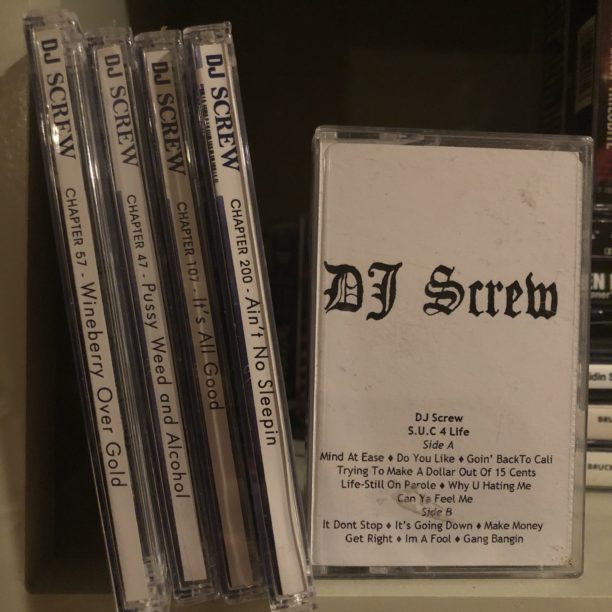

After checking stock, Big A says, “I got you,” and grabs copies of Wineberry Over Gold, It’s All Good, Ain’t No Sleepin’, and Pussy, Weed, and Alcohol. He takes my $45, and I’ve just purchased CDs for the first time in over a decade. No one mentions that this day, the one I had randomly decided on to pay my respects and my money, is the 18th anniversary of the day DJ Screw died.

DJ Screw died on November 16, 2000, of, according to his autopsy, “a codeine overdose with mixed drug intoxication.” The mixed drugs were PCP and Valium, but it was the codeine that got him, and the codeine that made him famous.

Texas Monthly’s Michael Hall remembers being the only white person at his funeral, and that “everyone was really sad about it, but a lot of people thought it might happen eventually. He was messed up toward the end, and it wasn’t a huge surprise to people.” Hall also learned, from his interviews with rappers like Big Hawk and Lil-O, how Screw mentored the younger generation, helping up-and-comers in the studio and putting out their tapes.

“Everyone was just sad to see him go,” Hall says of his death, “but there was this sense that there’s this whole new beginning. The teenagers and kids in their 20s, they saw him as example of what they could do.” That’s why Screwed Up Records & Tapes is still standing.

It started in the first place for two reasons: because people kept lining up at Screw’s home looking for tapes—in 2015, Houston rapper Lil’ Flip told an interviewer that he saw DJ Screw sell 15,000 mixtapes out of the trunk of a car in one day—and to ward off the imitators.

“A ton of bootlegs were being sold in Austin at couple of places—it was a big controversy in the community,” Hall says. “They were ripping off Screw, but also he was such terrible businessman he never set up deals with these places. He was a folk hero, a guerrilla music maker, but would get high and didn’t have any kind of infrastructure.”

The shop almost died, too. This is the second location of Screwed Up Records & Tapes, the first being about nine miles north, on Cullen Boulevard. An image of the original store, opened in 1998, graces the back of every CD sold in the West Fuqua store. Back in 2011, the owner of the building, a dentist named Dr. Poindexter, turned down a $100,000 offer from DJ Screw’s family to buy the property. For a while, it seemed the shop might cease to exist, and Bubb told the Houston Press that “everyone’s heartbroken about it.” They vacated Cullen Boulevard at the end of August 2011 and moved to West Fuqua shortly after. On the day I visited, the door continually swung open.

“I can’t think of any other parallel in any kind of music,” Hall says. “People want to be part of that because it was theirs.”

Last summer, people from all over the Gulf Coast flocked to Screwed Up Records & Tapes, when the most successful rapper from the Gulf Coast in a decade dropped a gilded head in the parking lot for the whole city to see. Hometown hero Travis Scott, teasing his upcoming album, Astroworld, named for a defunct local amusement park, had a gold inflatable bust of his head deposited directly outside the store, where social media directed hundreds of people to take pictures in front for the next few days.

It was a publicity stunt, but the name of the album evoked a sense of childhood wonder for the Houstonians who grew up riding the Texas Cyclone at the Six Flags location. “I went to Astroworld when I was like 10 years old, and it was the best feelings, best days of my life,” a man told the CBS affiliate in Houston. “To have an album named of that I hope it lives up to its name.”

Two months after the inflatable head left town, the video for “SICKO MODE” dropped, set against the backdrop of Screwed Up Records & Tapes, once again spreading the mythos of Screw to a new audience.

UT Austin associate professor of musicology Charles Carson, who was born and raised in Houston, researches music and tourism. I asked him why, in an age of unlimited access to information, anyone would bother going to a place like Screwed Up Records & Tapes.

“There’s a push back toward artifacts and materiality, and Screwed Up is a part of that,” he told me. That longing for the physicality is something Carson says that comes from the digitization of the forms of media people held sacred: movies, books, and especially music, noting that he has deleted more music in his life so far than his mother ever owned.

“People are so invested in place and space when it comes to music,” Carson says. “If there is physical place they can inhabit and imagine themselves in a place and time, it’s bigger than nostalgia.”

Langston Wilkins, who holds a PhD in ethnomusicology and grew up in Hiram Clarke, calls Screwed Up Records & Tapes both “the mecca for Houston hip hop” and “a heritage site.” Most fans of DJ Screw’s music outside of Houston only became aware of him after his death, gjving the store a kind of spiritual presence. Visitors to the the store, Wilkins says, “in some strange, metaphysical way, experience DJ Screw, even though he never set foot in that building. It’s closest we will get to the man.”

“Not to make it too big, but in Catholicism, it’s like communion is supposed to represent the body and blood of Jesus Christ,” Wilkins says. That’s what the shop is. A representation of the man and the myth.”

The night of my trip to the store, the friends and family of DJ Screw gather around the shop, each person holding blue and white balloons. It’s a celebration of life, and a remembrance of death, for those who belonged there. I watch it live on Instagram, the same parking lot, now bathed in darkness. Everyone seems to know each other.

“Whether it’s 1,000 or 100,000 or a million, we all know one thing.” Big Bubb says, as the crowd falls silent. “Robert Earl Davis touched so many lives. Just to think that it’s been 18 years since he’s been gone. The shop’s still open, the Screw Tapes still selling, the merch still selling. We don’t do it for the money. We do it for our dog, none other than the late DJ Screw, in the words of Pimp C, ‘the real king of the South.’”

There’s a loud cheer, until Bubb starts up again. “On the count of the three we’re going to release these balloons,” he says. “This is for you, Screw.” On three, they release the balloons, and simultaneously, they all scream, “Screeeeeeeeew.”

Inside the darkened store is a circular rack of T-shirts. One in particular bears the credo that keeps the store going in 2018, and, if Bubb and the crew have it their way, forever. Printed across dozens of green, gray, and, of course, purple shirts in all sizes is the shop’s slogan: “We Do It For SCREW Not For You!”