My maternal grandfather was an idealist in the truest sense of the word. Like many millions of others, he immigrated to what is now Pakistan from what is now India in his late 20s, though he was one of the minority who willingly abandoned his entire life in India.

Unlike his wife’s place of birth, my grandfather’s town hadn’t seen the kind of looting and communal violence that defined that bloody chapter in South Asia’s history. His family was well-heeled even after the Partition, and many of them had no interest in picking up everything and moving for an idea of a country where most of the people like them were refugees. But my grandfather really truly believed in the idea of a Muslim nation-state, a sort of commitment I envy now that I can barely align myself, even sarcastically, with a single political vision.

He was a graduate of Aligarh Muslim University, the school for Muslim Indians where the Pakistan independence movement had taken hold. Jinnah, Pakistan’s founder, visited the school often in the years before the Partition, meeting politically-minded young men who would go on to fill much of nascent Pakistan’s bureaucratic leadership, as my grandfather did.

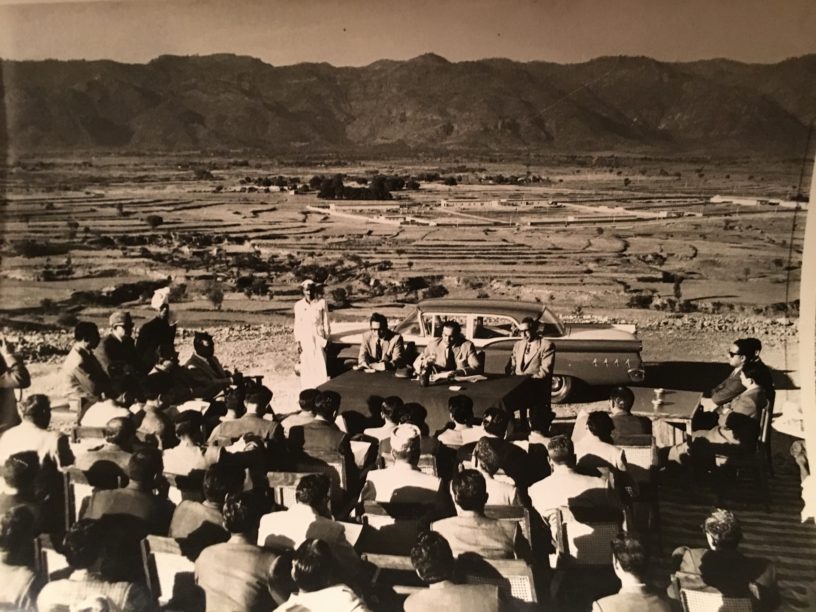

A planning meeting, late 1960s, in front of the lands that now make up Islamabad, Pakistan’s capital city. My grandfather is somewhere in this photo.

I grew up feeling a certain mystique around my grandfather’s legacy. I knew him mostly through my early childhood in Pakistan, when he wore pinstripe suits and attended salons with ambassadors and people like A.Q. Khan. Islamabad was still a small town then. He felt like an important guy, in that way I assume many grandpas feel to their grandkids.

By the time I was old enough to understand that he’d had a hand in creating Pakistan—and hadn’t been just a bystander to the events that shaped the country I live in today, but had been someone who took an active part in creating institutions and cities—we were living in the U.S., and visits “back home” grew further and further apart. The last time I saw him he was senile, barely able to recognize me after a stroke had rendered him half of the towering figure I grew up with. He still insisted on having the day’s newspapers on his hospital bed, and followed the headlines on TV as best he could.

My mother later told me that in one of his brief moments of lucidity he’d wept and told her he regretted the creation of Pakistan. That must have been around 2011 or 2012, the bloodiest years in recent memory. The country was bitterly divided—and not like getting in Facebook comment-fights divided, like killing each other divided. It was understandable that he came to regret the very concept of the country he’d believed in as much as he once had. I’m relieved that he passed away before the school attack in Peshawar, when the Taliban killed almost 200 children in an attack on an Army-run public school, though I fear his last years may still have been the worst of it.

Now that I live here, I often think about how soul-crushing it must’ve been, first to take part in the creation of a brand new nation-state, literally being a founding father, and then to grow so disillusioned with the country you’d helped create, to the point you wish you could take it back. That’s disappointment at a scale I can’t wrap my mind around, even though cynicism about Pakistan plagues just about everybody I know here. We don’t have what people like my grandfather had at stake. It was his entire life’s legacy. It’s why, as his grandchild, I’m on this side of the border, not that one.

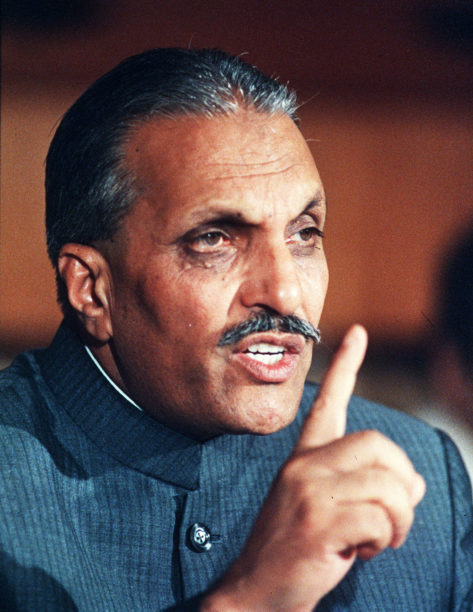

When the topic of why this place is so fucked up arises, I along with many of my friends and family point to one man as the beginning of the downward spiral that created the messy Pakistan that broke my grandfather’s heart: Zia.

His full title is General Muhammad Zia ul-Haq, but most everyone has shortened it just to Zia by now. Zia holds the dubious title of Pakistan’s longest-serving de facto leader, the face of our country for a decade, a ten-year period where he managed to create the kind of legacy where we still curse his name drinking overpriced and terrible smuggled booze on the humid nights when the power goes out.

Zia banned the public sale and consumption of alcohol, effectively forcing the thriving nightlife scenes in cities like Karachi underground overnight. But that’s among his least impactful legacies.

There’s a laundry list of things he just really fucked up, but chief among them is enshrining right-wing Islamization as a political institution, walking Pakistan straight into the Soviet-Afghan War, which effectively cemented the military’s now quasi-official relationship with terrorist groups on both of our major borders, and bolstering vast and overreaching military institutions so that they now always have the final say in Pakistan. This country prior to General Zia is barely recognizable in comparison with what it is today, or at least that’s what everyone who got to enjoy the swinging 60s in Pakistan tells me.

Zia’s rise to power is pretty standard, for a military dictator: he cozied up to the civilian government as the friendly military guy, the trusty general you’d want by your side when you line up for the next standoff with India. Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, then the socialist-leaning leader of Pakistan, appointed him Army Chief in 1976. A year later, Zia overthrew his sponsor in a military coup likely backed by the CIA. President Reagan, with his penchant for fascistic generals and tyrants, took Zia into his warm embrace a few years later.

Zia died a death befitting his sinister legacy. In 1988, a military aircraft carrying the dictator and several of his confidants—including the sitting US Ambassador—crashed with such force it blew into pieces. There are many speculations as to the cause of the crash, the most exciting of which is that someone smuggled a bomb into a case of mangoes gifted to Zia (it happened in August, when Pakistan’s mangoes are the sweetest in the world). Mohammed Hanif wrote a book about it, aptly titled “A Case of Exploding Mangoes.” It’s the theory I believe most whole-heartedly, because a piece of fruit killing that guy seems cosmically right.

But his death didn’t close the Pandora’s Box Zia had opened. His specter—and dude was spooky; he had these dark under-eye circles, and the dyed mustache of a cartoon villain—still hovers over this part of the world. The Pakistan I live in now, where people often die when they’re accused of blasphemy, where fear of the military’s wrath haunts the free press, where even typing this sentence makes me paranoid enough to consider deleting this whole thing, is Zia’s creation. It’s far from the intellectual haven for Muslims my largely secular grandfather, or many from his era, ever envisioned.

That’s why I assumed, in my naïve armchair analysis of Pakistani history, that my grandfather must have disliked Zia as much as I or any of the other roughly left-leaning Pakistanis I meet here. My mother, though, more familiar with his politics than most, informs me that my late grandfather hadn’t minded Zia at all. I was surprised that she would say that, considering Zia’s role as the prime mover of Pakistan’s downward spiral, at least in the narrative I had come to accept as truth. But there had been a worse villain than Zia, she said: Zulfiqar Bhutto, Zia’s predecessor.

“Bhutto created an environment of fear,” she told me. “Even as a seventh grader I was scared of Bhutto’s ‘special forces’”—paramilitary units that had arrested and assaulted the political opposition during the tumultuous years before Zia’s dictatorship. My grandfather, then the Director Lands of Islamabad, the bureaucratic office determining the land allocation of the then-newly-created Islamabad, lost his job in Bhutto’s great purge, when any who questioned his power were summarily sacked. He didn’t mind General Zia because it meant no more Bhutto. The enemy of my enemy is my friend, etc.

But Bhutto did far worse than just fire my grandfather. The 70s were among the most humiliating and violent years in Pakistan: Bhutto oversaw the bloody genocide that was the Bangladesh Liberation War, when Pakistan lost “East Pakistan,” its massive territory on the other side of India; instituted systematic political oppression, including the special forces my mother feared; and introduced some of the more harmful policies that General Zia continued, like the first ban on alcohol, and the condemnation of an entire minority as blasphemous. In short, Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, or ZAB as people here sometimes call him, had his own laundry list of shit he really fucked up too.

It turns out that almost every decade of this country’s history is marked by a dictator with his own dark legacy. Pakistan has seen more years of military dictatorship than anything else, the most recent being General Pervez Musharraf, a rare example of one who left semi-willingly in 2008. The few civilian governments squeezed in between periods of military rule have been quite prone to dictatorial tendencies themselves, the administration of ZAB being among the worst.

These characterizations are contested, naturally, depending on your ethnic background, class, and army-affiliation. In one of the funnier Letters to the Editor exchanges I’ve read here, a Pakistani-American student at Princeton wrote a letter imploring Pakistanis to reconsider their blind worship of flawed figures like Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto after seeing the debate around Woodrow Wilson on his own campus. (Zulifqar Ali Bhutto is celebrated as a martyr along with his daughter Benazir, the iconic first female Prime Minister of Pakistan.) An outraged older gentleman, who presumably fit neatly into the cult of personality that fuels the Bhutto family’s popularity in Pakistan, was appalled by this letter, enough that he wrote his own. “Bhutto is rightly remembered as a martyr for democracy,” he wrote in his response, “since a bloodthirsty dictator unjustly hanged him on trumped-up charges.”

The exchange is emblematic of the fraught, nauseatingly complicated and deeply entrenched politics of this place. It’s why the average Pakistani citizen can casually refer to the deep state, and why some families have been banning politics as a dinner table discussion years before your “How To Talk About Trump at Thanksgiving” thinkpieces came around. It’s a toxicity far beyond “the discourse”: people are killed here because of these fault lines and divisions. When a country is put through existential crises on a dictatorship-by-dictatorship basis, there’s little in the way of national identity left to hang on to. You protect your own and roll with the punches.

I long held the belief that my grandfather felt regret at Pakistan’s creation because of the bloody years of the War on Terror, but now I know that he saw far worse. I wonder whether the regret came to him early, or if it was the last straw, his final impression of the history of a country he was able to witness from birth until his own death.

I’m still new here in Pakistan, so I’m prone to oversimplifying the things I see into easily digestible ideas, bullet-point lists of things that went wrong back when, mental flashcards that might keep my foot out of my mouth depending on who I’m talking to. But I need things to be that way for now. When you flick the flash cards away, the reality is far too chaotic, too dizzying to grasp. The oversimplification helps me process Pakistan like a Wikipedia entry, instead of the gut-wrenching place it can be.

When I do let the gravity of it all hit me, though, in the brief instances where my deep sarcasm is on pause for long enough to let me feel something, the pain feels like a fleeting visit to my grandfather, like a brief conversation about a topic we never had a chance to discuss: his country.