I grew up in a small village in Norway called Å, a place no one’s heard of. At 19, I left, and after our house was sold a few years later, no one in my family has really been back. Because why would we? Why would anyone?

A town with a one-letter name is unusual, though. The A with a small circle above it is one of three extra letters in the Norwegian alphabet, pronounced like the vowel sound in “more.” As a word, Å is Old Norse for “still river,” the kind of stream so calm you can see your reflection in the water. The village had a river, so it was Å. And unfortunately for the teenager I was, Å was as stagnant as its name. Nothing much happened there.

Å has always fascinated visitors, however, and the house I grew up in was next to a central tourist attraction: the town sign. It was a standard issue roadside sign displaying the white Å on a blue background. But every month or so, when I was growing up, I’d look out the living room window and see that a car had pulled over, and someone had run out to take a picture of the sign.

“They’re photographing it again,” I’d call out to whoever was around. It never stopped being amazing that someone would stop to take notice of something that, to me, was so commonplace.

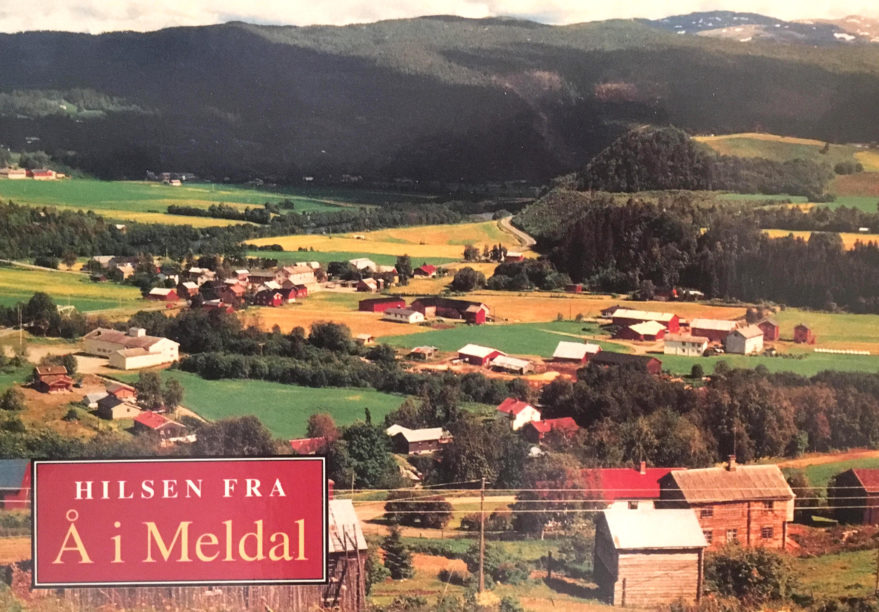

If you’re not a teenager, Å is a beautiful place where you can take peaceful walks and hear yourself think, a good place for reflection. Located about a third way up the country, just where the fat bit ends, it’s tucked into a green valley at the foot of a mountain where two rivers meet: the whitewater Resa and the much more serene Orkla, the å that gave the town its name. Fishermen spend hours fly fishing in the Orkla, thigh-deep in the water, and low-slung white farmhouses dot the landscape next to red barns. The fields turn yellow as the grain matures toward the end of summer.

As a child I’d walk barefoot on the dirt roads by our house and listen to the sound of the grain rustling in the wind. My mother called it “grain wind,” the sound wheat makes when it’s ready for harvest.

When I left in the nineties, the 300-or-so inhabitants were vastly outnumbered by cows, and though Å has grown a little since then, it’s still a “blink and you’ll miss it” sort of place as you’re driving through. At the central crossing is a grocery shop—which also, by necessity, has a bit of everything else—and there are two nurseries, one for children and one for flowers. The school I attended until I was twelve is no longer a school, deemed too small to be worth keeping, so local kids now take a ten-minute bus ride to the next village over. It was a blow for the village to lose its school, but I think the kids are better off; I hated going to such a small school, barely fifty pupils in the whole building. I knew the birthdays and phone numbers of all eleven kids in my year, but only one was a real friend.

It’s hard to find your people in a tiny place. Chances are, they’re elsewhere. I suppose Å might have been a childhood paradise for a different kind of kid, but I was bookish and “different” in that indefinable way that makes kids on pick on each other. Worst of all, I was an indoor kid in a place that’s all outdoors.

But sometimes that was lovely too. On the rare hot day, we’d drive for fifteen minutes into the mountains, to Resvatnet, which warms up all summer until you can finally run in the shallows and swim in the straw-colored water. Or at Easter, we’d make the same drive to the same lake, which freezes over in the winter, and walk very slowly on skis across the bright white snow. Finding a nice spot, we’d build a fire and grill hotdogs and drink hot cocoa at the foot of Resfjellet, the breathtaking mountain at the entrance to wilderness that leaves you in awe you every time. It’s nothing compared to the big-ticket mountains and fjords that make Norwegian landscapes a global tourist attraction. In the moment, though, you don’t think about that.

Like Norway itself, Å takes a pride in its unfussy salt-of-the-earth quality. In 1860, the poet Aasmund Olavsson Vinje wrote a travelogue (Ferdaminni fraa Sumaren 1860) which contains Å’s closest thing to a claim to fame: a story about being served workers’ oat porridge at Grut farm at Å. “It had spikes like the bristles on a pig’s back, and it was black,” he writes; “I was given good milk with it, and I ate and ate, and it scoured down my throat like when a spruce tip is pulled down a chimney.”

The porridge was rough, and Vinje had a good sense of humor about it—”It was as if I was shivering from all this enjoyment,” he said, “present in each bite”—but make no mistake: it was proper. To Vinje, the porridge was proof of just how Norwegian the Viking god Thor really was—a people’s god with a good attitude and eagerness to strike, whose blood was the same as these people’s blood. “I didn’t properly understand all this grandiose Norwegianness before I ate that porridge,” he wrote. What charmed Vinje about that unremarkably remarkable porridge was how you had to take a little bit of pain with the enjoyment, out here in middle-of-nowhere Norway. In honor of this historic meal, every year, Å hosts Porridge Day (Grautdag) where everyone eats Vinje’s porridge, except it’s a distinctly nicer one: the oat is properly milled so it goes down smoothly, and no one goes home feeling like they’ve had an encounter with a thunderous god. But it’s probably for the best.

“Everywhere is nice when it’s sunny,” my mother likes to say. But my memories of Å are overwhelmed by the endless winters, packed into layers against the freezing cold, wobbling along icy roads, and surrounded by the gloomy Nordic light. I dreamt of sunshine and the city, wanting nothing more than to meet different kinds of people whose lives had been different to mine. And so I taped over the Norwegian subtitles at the bottom of the TV screen to perfect my English, and—marveling at the sight of people drinking takeaway coffee in films, and having food delivered to their door—taught myself how to make barista coffee and to eat with chopsticks. The city, I figured, would be where I could learn who I was.

I live in London now. It’s crowded here with eight million people, and it’s noisy and dirty. I love it more than I’ve ever loved anywhere else. Go and stand on the South Bank and look out over the Thames; this is a real tourist attraction. I think about Å-sign sometimes when I push past crowds of tourists; I don’t see them photographing Big Ben much—what Londoner would hang out in front of Big Ben?—but having a drink in the Ten Bells pub in Spitalfields means you’ll run into the Jack the Ripper walking tour, and everyone, including Londoners, can enjoy sitting down for a moment by the fountains in Trafalgar Square, watching teenagers climb the giant lions. There’s always traffic and the sky is never fully dark; around the corner in Chinatown there’s late night dumplings and a coffee place that never closes. This is a city that’s worth pulling over for.

When I drove through Å a few summers ago, I hadn’t been back in over ten years. I would have passed through in a matter seconds had I not slowed to a crawl, and then found myself—almost without making a decision—pulling over next to the bridge over the Resa. I got out of the car, trying to make sense of this alien, familiar place, which had been so rarely on my mind the past decade.

It was like meeting someone you haven’t seen in years, and they look exactly the same and also completely different. The village felt small, literally small although I’d not actually grown since I left at 19. In my mind, Å had stayed the same size as it had appeared when I was a child, and I felt like a giant. I had literally outgrown the place.

I’ve always said that Å is a beautiful place to be from; like Vinje’s description of the porridge, it’s a compliment with a barb. The world is a big place, and I’ve grown up and moved on, and Å has moved on, too: a café has opened since I left and it’s pretty nice.

Å isn’t my home anymore, so the day I went back I did what tourists do. I pulled over at the village sign, in the same spot where I’d seen so many people do the same, and I took a picture. Though it looks completely different, the house I grew up in is still there—and I’d like to think it’s home to kids who watched me take that photo and who did what I used to do: roll their eyes at why someone would ever stop for something so unremarkable.

Jessica Furseth