When the #MeToo movement was uprooting men from important spaces in North America for sexual violence in early 2017, African feminists hoped they could seize the moment to amplify existing activism and demand public accountability. In Ghana, there were public conversations on- and offline about sexual violence, but there were no shocking revelations about how some men used their power to abuse women across society. Instead, men joked that women wouldn’t even dare to name names because no one was going to hold any powerful man accountable and a reckoning of the U.S. sort would turn the country on its head as most men would be indicted. And so Ghanaian women did nothing with the moment.

At least not right away.

In 2014, 19-year-old Ewuraffe Orleans Thompson filed a police case against popular entertainer Kwesi Kyei Darkwa (KKD) alleging that he had raped her. In response, the media scrutinized and shamed her, choosing to side with KKD. Influential lawyers rallied to defend KKD, and showed up in court to support him. During the trial, Thompson received such intense harassment from KKD’s supporters that she withdrew the charges. Soon after the court case, religious leaders attempted to restore KKD’s reputation by holding a thanksgiving service. Two powerful institutions—the media and the church—chose to support an alleged abuser over a young victim.

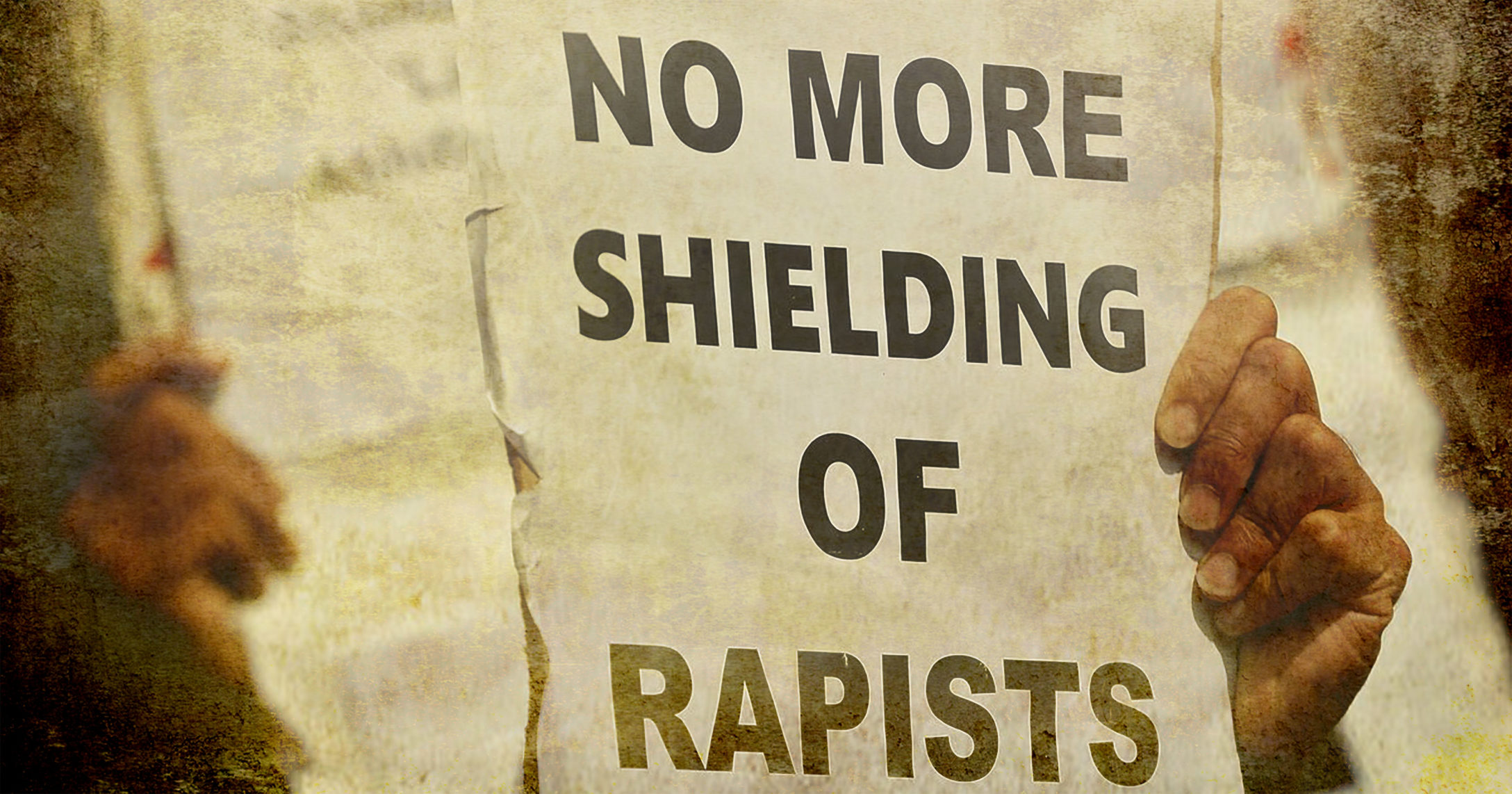

Ghana has a problem with rape culture.

In December 2018, a comedian known as Waris tweeted, “Sarkodie’s daughter is becoming ripe. Very soon, we people will tear and eat,” suggesting that the popular musician’s Sarkodie’s two-year-old daughter was nearly old enough for sex. Ghanaian feminists pointed out that the tweet positioned young girls as meals waiting to be consumed by groups of men, and that this attitude toward girls and women—as consumables—was emblematic of a more general rape culture. Sarkodie himself didn’t seem bothered that a man almost his age had suggested that his toddler was almost ripe for sex, but feminists still pushed for a retraction and apology.

Waris apologized. But the apology started with, “If I offended anyone,” refusing to acknowledge the systemic problem feminists had pointed out. Waris’s defenders urged Ghanaian feminists to forgive him. Feminists were urged to consider Waris as brother, friend, and a partner who had erred.

This strategy is common in Ghana: whenever a man is publicly called to account for his bad behavior by feminists, his defenders invariably ask that he be treated as an errant family member who should be forgiven. Feminists are positioned as family members who grant absolution, with the effect that necessary conversations about abusive systems are suppressed. Even after the apology, other entertainment personalities supported Waris, with one claiming, “Sarkodie’s daughter will grow so we cannot judge Comedian Waris.” But the core of this defense is that Waris was wrong for picking on a two-year-old, not that sexual violence against girls and women is wrong.

The danger girls face from sexual predators was also highlighted when a comedian and school teacher, Teacher Kwadwo, solicited tips for how to rape his students on his Facebook page. Once again, Ghanaian feminists organized to have the teacher sanctioned, and Teacher Kwadwo lost a contract with Huawei and received a warning from the Ghana Education Service (GES). Once again, feminists were urged to forgive him by his defenders, who insisted that Teacher Kwadwo had only made a distasteful joke. Unlike Waris, Teacher Kwadwo did not apologize for his sentiments.

In a Facebook post, popular journalist, Afia Pokuaa, called on feminists to “do unto men as we want them to do unto women.” She argued that feminists who criticize Ghana’s rape culture impugn the integrity of all Ghanaian men. In a subsequent post, Pokuaa narrated her own experiences with sexual violence in high school and on a trotro. Yet, instead of using these experiences to emphasize the problem of sexual violence, she admonished against “making Ghana look worse than it is by portraying every man as a rapist.”

Pokuaa is the founder and president of SugarDem, a women’s group formed to counter the efforts of feminist group Pepper Dem Ministries (PDM). Founded in 2017, PDM advocates for the rights of women and girls mainly online by challenging toxic narratives embedded in Ghanaian culture. In contrast, SugarDem aims to to “pamper, lick and sugar” Ghanaian men. While PDM aims to dismantle patriarchal systems, Pokuaa’s group hope they will profit from “pampering” men. Pokuaa is a journalist with a huge following. By attacking feminists over the existence of rape culture, she is minimising sexual predation. Her response highlights media’s complicity in rape culture.

Ghana’s media frames rape as individual abomination instead of a systemic problem. Local language news presenters giggle and moan when reporting on rape, diminishing the violence victims suffer. In one instance, an interviewer on a local language radio station asked a 17-year-old girl who had been raped repeatedly by her father why she didn’t run away, and asked if the victim stayed because she enjoyed the rape. Victims are routinely re-victimized in media coverage. Even stories about minors include their names, their communities, and sometimes details of family members. No clear policies and regulations exist to govern how media should address sexual violence and protect victims, consequently, victims and their families are subjected to sensationalism, prejudice, and sexist attacks. To avoid this dehumanizing media coverage, families often settle rape cases at home. Often it’s vulnerable women who face these barriers to justice, but it’s not just them.

The media’s disregard for victims of sexual violence, which includes joking about the violence and shaming victims, creates a fertile environment that encourages sexual violence against women and girls. A 2015 study by the Ghana Statistical Service found that 30 percent of Ghanaian women and 23.1 percent of men experienced sexual violence at least once over their lifetime. A six-year survey conducted by the Domestic Violence and Victim Support Unit (DOVVSU) of the Ghana Police Service indicates “approximately six women are likely to be raped every week.” The survey which covered 2011 to 2016 revealed that nine women were raped every month in 2012 while ten women were raped every month in 2013. Within the same period, only one man was assaulted. Despite these numbers, experts believe rape is still significantly underreported in Ghana.

More and more Ghanaians have become aware that rape is a crime and are choosing to report rape cases to the appropriate authorities, due, in part, to media coverage. But reporting rape to the police alone does not mean victims will get justice neither will extensive media coverage, especially if that coverage chooses sensationalism over justice, and mocking victims over holding perpetrators accountable. Ghana’s media can be a strong advocate for social change and can help transform conversations about sexual violence.

Powerful men are seldom held accountable for their actions in Ghana. But just because it is unsafe to out rapists publicly doesn’t mean Ghanaian women and girls have to endure the culture of impunity. The brave Nigerian women who went on the #YabaMarketMarch to protest unsolicited touching and groping in that market have shown that we do not need to name rapists to change public behaviour. Since the march, there have been testimonies indicating that men sellers have been respectful of women’s bodies. The 2014 My Dress, My Choice campaign made Kenyans aware that groping and other forms of harassment weren’t unacceptable. Recently 37 women working at the African Union headquarters in Addis Ababa triggered an investigation after they signed a petition complaining about widespread sexual harassment. In November 2018 South African feminists women staged a total shutdown across that country to protest gender-based violence. None of these countries is a hundred percent safe but women are not waiting for the patriarchy to topple itself.

Whereas #MeToo highlighted the many ordinary ways girls and women face sexual threats and violence, and its most prominent targets were powerful men, these movements by African feminists in Nigeria, Kenya, and South Africa have focused on the many ordinary ways women navigate public space. They have attempted to reclaim markets and streets, bus stops and public parks, insisting that girls and women have the right to share and enjoy public spaces without harassment. And while these movements take local spaces as their scenes of activism, they are part of broader feminist pan-African movements. Each act of challenging patriarchal power in one space inspires other spaces to challenge patriarchal power.

Together with advocacy groups, feminists have been at the forefront of condemning rape culture, demanding justice, and teaching consent. The whole time, Ghanaian men, especially public intellectuals who have opinions on everything from how feminists should feminist to cooking have been silent. Their silence is telling and damaging. We know rape will only end when Ghanaian men hold themselves accountable. It is time.

Editors’ note 12 April 2024: This piece was amended to protect the privacy of a victim mentioned without their consent.