Everything must change so that things can remain the same. In Tomasi di Lampedusa’s 1958 novel The Leopard, this explanation is given by Don Tancredi—a young Sicilian aristocrat—for joining Garibaldi’s troops on their way to overturning Spanish rule over the South of Italy. This cynical epitaph to the Italian Risorgimento is also one of the most succinct expressions of the principle that has regulated the political development of the country since before it was even born.

The principle was soon given a name: trasformismo, or the art of forming governing coalitions by picking from representatives of the opposition, who might (officially) be persuaded to switch sides in the name of political compromise and putting-the-country-first moderatism or (less officially) in exchange for sinecures or other forms of personal advancement and patronage. The word was first used in 1882 by incoming prime minister Agostino Depretis, leader of the parliamentary left, in a speech in his native Stradella: “If a man wants to join our ranks, if he wishes to accept my modest program, to transform himself and become a progressive, how could I reject him?” (My emphasis.)

At this time, the country had no political parties in the modern sense. Elected members sat on the left or right side of the house based on loose affiliations and even looser sets of principles. They owed their allegiance first and foremost to their constituents—which in 1882 still meant male voters above a fairly comfortable level of income, or roughly 2 percent of the whole population—and even more so to the particular individuals and power structures that had helped to get them elected. Then there was a senate whose members were picked by the king, and was steadily filled by noblemen, landed gentry, and industrialists, thereby ensuring that a high level of conservatism be maintained throughout the early decades of the new nation.

In fact, it would be more accurate to say that the political principle I have been describing has not one but two names: trasformismo and immobilismo.

If trasformismo was the political doctrine, a strategy for forming governments that kept a firm anchor to the center (in the name of dealing with a seemingly permanent state of economic and social crisis), immobilismo was the effect of that strategy, a reassurance to those in power that no matter how much things changed, they would remain the same. Trasformismo was the illusion of change, and immobilismo was the reality, perpetual stasis.

This stasis, this ferocious conservatism, came at a considerable price among those who had placed their hope in the country’s hard-fought unification, from the Southern peasants struggling for land reforms that never came to the impoverished industrial workers of the North who lived and labored in the most abject conditions. In 1894, years of strikes and insurrectionary activities conducted by the leagues of Sicilian farm laborers and urban workers known as Fasci were crushed by 40,000 royal troops, and in 1898—at the opposite end of the country—an artillery division commanded by General Bava-Beccaris opened fire against peaceful protesters in Milan, killing 300. When expatriate anarchist Gaetano Bresci heard (all the way in Paterson, New Jersey) that king Umberto I had given Bava-Beccaris the highest military honor for this act of bravery, he bought a one-way ticket home, procured a gun, and killed the king.

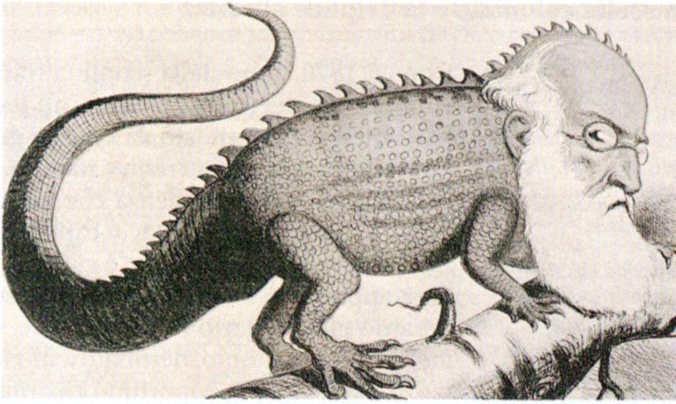

For the first two decades of the twentieth century, an astonishingly canny operator by the name of Giovanni Giolitti dominated the political scene, becoming prime minister on five separate occasions as the leader of as many different coalitions. And in 1921, in a desperate attempt to stem the rise of the socialist party—at the tail end of the period of unrest, mass strikes, and factory occupations known to historians as the Red Biennium—he formed an alliance with Mussolini’s nascent movement, having enjoyed for some time the support of his paramilitary Fasci, even in name a mockery of the workers’ leagues of recent memory. This was the hubristic apotheosis of trasformismo, driven by the apparent belief that even the most extremist of forces could be co-opted and moderated.

Giolitti failed, of course. Mussolini seized power, and (among other things) sentenced communist leader Antonio Gramsci to a 20-year prison term. But a prison term that was designed, in the words of fascist public prosecutor Michele Isgrò, “to render that brain of his inoperative” had the opposite effect. Gramsci used the time of his incarceration to study and write almost incessantly, and among many other topics, he turned his attention to trasformismo.

Gramsci’s understanding of trasformismo is connected to his theory of “passive revolution,” a social and economic transformation undertaken without the active participation of ordinary citizens. In his 20th notebook, he characterizes this hollowing out of the political sphere in terms that are eerily applicable to the present day:

If the ruling class has lost its consensus, that is to say it is no longer “leading” but only “dominant,” capable of exercising its power of coercion alone, this means that the masses have become detached from traditional ideologies, no longer believe in what they once believed, and so forth. Crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born: in this interregnum, a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.

The old is dying and the new cannot be born. Or, to put it another way: everything must change so that things can remain the same.

After the war, Italy jettisoned Mussolini’s barbaric dictatorship, but only with the triumphant return of trasformismo. Nearly five decades of uninterrupted Christian Democrat rule followed, paradoxically (and famously) through constant elections and an incessant shuffling of minor party support and cabinet roles; a gentleman by the name of Giulio Andreotti was able to beat Giolitti’s record by becoming prime minister on seven separate occasions. Then Silvio Berlusconi happened, as if to demonstrate that you can only play this game so many times before the paralysis of immobilismo seizes so many organs of the body politic that the disease becomes uncontrollable. And so now, after Berlusconi’s own demise, the members of the current Italian government resemble not so much a ruling political class as a collection of morbid symptoms: braying, racist populists, on the one hand (Matteo Salvini’s League), and the most dangerously naïve exponents of post-ideological qualunquismo on the other (Beppe Grillo’s Five Star Movement).

If you think you can make a similar diagnosis of your own country, it may be that this state of rolling, permanently managed crisis—for which the Italian vocabulary has the twin names of trasformismo and immobilismo—is not a feature of only our political system; it may be a broader descriptor of all liberal democracies as they unravel.

Giovanni Tiso