If you grow up in Hornchurch, one day you will have to choose: you either remain there your entire life, or you leave forever. Properties are bought, not rented. I think I’ve left it forever; partly because I grew up dreaming of escape, but also because an empty house isn’t a home, and once my parents were gone, the house I took my first steps in had to be sold anyway, to pay off the inheritance tax.

The town is in Havering, one of London’s thirty-two boroughs. It’s not Westminster, Camden, or Islington, the central London boroughs with tourist attractions and lovely old terraced townhouses (referred to as “inner London” when there’s a stabbing). Havering very rarely gets into the news. It’s out on the north-east edge of the city, transferred into London from the county of Essex in the 1960s. A buffer between ever-growing London and the Green Belt, it’s too built-up to feel like the countryside, but still too verdant to feel like London: green and pleasant and so quiet that you can hear the birds singing in the trees. There is an equestrian centre ten minutes’ walk from the house I grew up in; horses clomping up and down the next road was a common sight during my childhood. An hour on the train and you can be at the sea, or in the centre of London; stay off the train (and avoid the news) and you can pretend that London isn’t out there at all.

I grew up in a district of Hornchurch called Emerson Park, where the streets are called avenues and lined with trees, avenues so quiet that children can play in the middle of the road. Or at least we did, back in the nineties. I’m not sure what the kids do there now.

In an album somewhere, there are annual photos of my mum holding me under the tree across the road from us, which blossomed each year when my birthday came round in late April, “the most hopeful time of year,” as she put it. We would stand under the canopy of pink flowers, just in the road, never bothered by a car. I ought to put those photos in a flipbook, to make a little film of growing up: being held, getting too big to be held, then finally standing next to your parent, as tall as them or taller, an adult height that tugs at the heartstrings of anyone who ever knew you at an age when you could be picked up.

Those blossoms come earlier and earlier now. When I was last in Hornchurch, the tree was in full pink bloom, in March. A beautiful, nostalgic sight now shadowed by fear: photos of me becoming a person show how climate change has crept up on us.

Hornchurch is a driving town. It’s a part of London, but it’s the outer limit, where public transport will take you into the city, but no farther out. And so, people drive, reflecting their orientation, outward, away. In the time before cell phones and Google maps, I would cycle as far as I could through the quiet roads, before getting scared that I would somehow lose my way home. (When someone built a tiny internet cafe in a spare bit of their house, that, by the very late 90s, overtook cycling as my escape). But Hornchurch was incredibly safe, and still is, safe in a way that appeals to people who want children and in the way that those children grow to resent. As I grew, I looked inward: I stockpiled “Transport for London” leaflets, looking to make my own journeys into London. It was part of growing up to turn down the plentiful supply of parental lifts–to shrug off my parents’ fears that I would be kidnapped off of a train platform–and to make my own way into the city. Living on the doorstep of London, I wanted to devour the city whole.

In 2016, 71% of Havering voted to leave the EU, the borough of an otherwise heavily pro-EU London with the highest vote to leave. I was saddened and unsurprised; in Havering, it was a vote for gated communities and nice cars and no train stations being built too close to my mansion, thank you. It’s the way you vote when 89% of the population is White British, when it doesn’t look like London, and you live here because you don’t want to live in London (but like to keep a watchful eye on it). “The strongest correlation between the vote for Leave and any key demographic measure,” a data journalist, John Burn-Murdoch, tweeted, “is the share of people holding a degree. But even here, regional patterns are clear: London boroughs stand out in the tail on the right, with higher education and low Leave numbers.” There, in one of the charts he tweeted, I saw make its way into the headlines: “Havering was by far the most pro-Leave area of London. It also has the lowest share of people with degrees.”

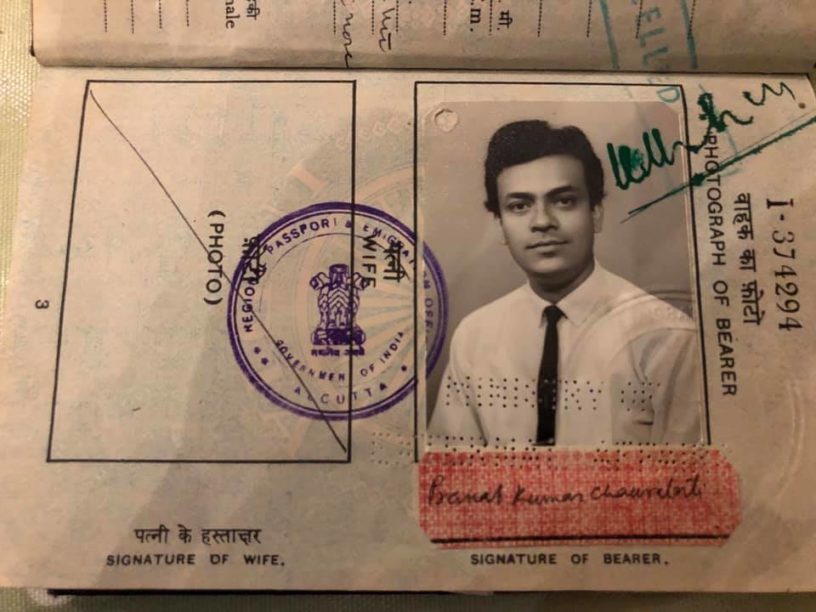

Such things make me wonder why I was so different. Growing up, I didn’t particularly notice that I was part of the 11% of the non-white population. But perhaps it did make me different; my parents were from somewhere else, an unimaginable one-way journey halfway across a world without FaceTime or wifi or low-cost airlines. Perhaps because they’d come so far, with so many stories, I always looked beyond the safe little bubble of my hometown.

We ended up in Hornchurch because my dad followed his older brother Nirmal from Calcutta to London, and Nirmal had married my Auntie Eileen, who was from Hornchurch. Not all of us get to hear about all the coincidences and love stories and surprise twists that lead to us being born where we were born, but I did, and that was it. There had been other journeys, planned or dreamed of, but never made: New Jersey, Australia. But those other lives fell through, those phantom hometowns.

I’m not in Hornchurch often now. I live in north-west London; I work wherever my laptop is.

My parents both died before my 20th birthday, and three years later, my brother and I sold that house in Hornchurch. It was that, or face an inheritance tax bill we couldn’t pay. What would we do with an empty house? We were both leaving. We were growing, moving on, and Hornchurch changes too slowly, refusing the EU and freedom of movement and everything it represents. Hornchurch is a place that wants the world to stand still, like a helicopter parent. Hornchurch wants you to buy, to settle, and remain. But if there’s one thing the world won’t do, it’s that. Brexit is supposed to be about Europe, but I feel it at home; it feels to me like the doors are closing on the freedom my parents had, to leave India and go west to become Europeans. That’s what the people of Hornchurch voted for. So I stick to London these days, and rarely venture back.

Suchandrika Chakrabarti