The music video for Kulwinder Billa’s “Yaad Yaar Di” opens in California’s San Joaquin Valley, where a pair of mechanics work in a lot full of 18-wheelers. They have their radio tuned to 93.1—the frequency of a popular Punjabi station that broadcasts from Vancouver—and they listen as the host announces the beginning of a special show dedicated specifically to truck drivers. Speaking a mix of English and Punjabi, she invites anyone behind the wheel to share a poem or a song over the air.

Billa, an actor and singer famous in Punjab, plays the role of the first caller. With a bhangra beat rolling behind him, he attempts to describe the experience of a homesick immigrant truck driver: he remembers old days vacationing with his family in the Himalayas, he describes long hours on the road and he shares news that his friend Aman has become successful enough to buy a truck of his own—become an “owner-operator” as they say in the industry. Offering a mix of optimism and melancholy, the refrain—”Ghutt phad da steering nu / Ho jaddo yaad yaar di aave x”—translates to something like “Palm holds the steering wheel as I remember my friend” while the video cuts lonesome road footage with scenes that show Billa applying for a Green Card. When the Green Card gets approved, he returns to India to celebrate with his family.

“Yaad Yaar Di” tells the story of one fictional immigrant, but there are thousands of people in North America who are living the story described in its lyrics. Statistics on the trucking industry are notoriously inaccurate, but a recent CBS report estimated that there are more than 30,000 Indian-American Sikhs currently driving trucks in the United States. (The Sikh religion originated in Punjab and remains prominent there.) A group called SikhsPAC, founded in response to the anti-Sikh violence that followed 9/11, puts the number closer to 150,000, including Canadian Sikhs in their count. These drivers are particularly prominent in states like California and New Jersey. The North American Punjabi Trucking Association believes that 40% of California’s drivers come from Punjab, though a survey conducted by George Mason University was more conservative: by their numbers, immigrants in general make up 46% of California’s drivers, with immigrants from Mexico accounting for a plurality of that figure.

These statistics attempt to quantify patterns of immigration already apparent to anyone traveling through the San Joaquin Valley, like Billa’s protagonist, or across the Northwest, where truck stops often include Indian food among their offerings. Look out the window in Laramie, Wyoming, and you might see a Sikh owned truck stop, the Akal Travel Center, that includes a small Gudwara where drivers can pray. Turn on the radio in British Columbia or Calgary, and you might hear either RED 93.1 (the station the mechanics listen to in “Yaad Yaar Di”) or its sister station RED 106.7 broadcasting Punjabi music throughout the day. Further South, Punjabi Radio USA airs music and news tailored to truckers from AM antennas located across California and into Nevada.

Listening to these stations, it becomes clear that “Yaad Yaar Di” is not the only song of its kind. In “Transportiye,” Sherry Mann, a singer from Toronto, narrates a route that crosses the border between the U.S. and Canada. He describes playing the Indian card game Seep with other drivers and repeats how much he misses his girlfriend. “Ik teri yaad dooja laare dispatcher’an de,” he sings. On one side is your memory, and on the other is the dispatcher’s false hopes.

Mann ends his song by insisting that his hard work behind the wheel will pay off—someday, like the cousin in “Yaad Yaar Di,” he’ll purchase a truck of his own. Dalbir Bhangu, from California, shares this attitude in his track “Akh Baaz Vargi.” Bhangu describes trips that last eight days and a loneliness that requires him to “make long routes his friend.” He tells himself that this work will give him the money to build in his village a mansion like the Taj Mahal but also imagines how new immigrants could transform life in North America. At one point, he sings words that translate to:

Let the world say anything, but in our hearts, we are still Desi

When we Desi people all gather around

Then America sounds like the Punjab

Trucking, needless to say, is an iconic American vocation. When I was a kid, my toy box included not just miniature tractor-trailers but a set of Texaco pencils that my grandfather, a Teamster and long-haul driver based in Boston, gave me to scribble with as a kid. But in a nation where much of the labor force is made up of immigrants, the trucker hat may no longer be the profession’s definitive symbol.

This is also a nation where many immigrants can be deported simply for driving a car. Immigrant truck drivers usually receive temporary protections from H-2B visas, but doing some work in the immigrant justice movement, I’ve seen firsthand just how complicated it can be to struggle for civil rights without the symbolic and legal shield of citizenship. Punjabi music is a point where diasporic cultural identity, immigrant rights, and organized labor converge. That’s part of the reason I’ve developed an increasing fascination with this growing body of music. Artists like Billa, Bhangu and Mann aren’t just making America sound like the Punjab—in doing so, they are writing an unexpected new chapter in the history of an art form that I, at least, had always taken to be archetypically American. I’m talking, of course, about the trucker song.

In the United States, trucker songs have usually fallen under the umbrella of country music. Trucker country, as the subgenre is often called, dates back to the late 1930s, when the Western Swing group Cliff Bruner and His Texas Wanderers released a song called “Truck Driver’s Blues.” Bruner’s home state is significant: In the first half of the 20th century, the development of country music was closely linked to the development of what political scientist Timothy Mitchell calls our carbon economy—that is, an economy that uses the extraction and burning of fossil fuels to achieve unlimited, year-after-year growth.

The first commercial country records were released in the 1920s, just as U.S. coal production was hitting its first peak. Country and coal shared similar geographies: these early records came primarily from Appalachia, where coal was extracted, and the Southern Piedmont, where it was burned in factories—particularly cotton mills—worked by artists like Fiddlin’ John Carson and Dave McCarn. Both coal and the commodities produced in these factories circulated primarily via railroad, and in country music, these were the domain of Jimmie Rodgers, a star billed as the Singing Brakeman.

The rise of trucker country, however, signals the transition to a new form of circulation—the motor vehicle—with engines powered by energy derived from a new source: oil. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, coal miners exercised political power by strategically blocking the flow of energy. Shutting down that process of extraction, production and circulation, they won better working conditions and new political rights. Their strikes closed mines, and their blockades halted trains. These were militant workers, and capital developed oil as a way to strip them of their power, in both senses of the word. Once laid, oil’s pipelines were harder to disrupt than coal’s trains, and unlike coal, oil was taken from ground by small teams of workers, located far from most industrial centers.

In the early 20th century, this meant places like Tomball, Texas. Tomball was Cliff Bruner’s home, a small town near Houston where speculators spent decades probing for oil before striking a 100-foot gusher in 1933. Tomball had been a railroad hub, but in the future, these sort of remote communities would send and receive goods through a new form of commodity circulation, which brings us back to long-haul trucking.

Compare, with this history of strikes and blockades in mind, the truck and the train. With the truck, circulation becomes more flexible. Having a steering wheel, the truck can change course more easily than the train. Moreover, the truckers themselves are spread across literally thousands of miles, almost completely isolated from fellow drivers.

These changes should have made it difficult for workers to organize, to develop the militancy of early 20th century coal miners. That’s one reason why it’s so remarkable that trucker country eventually became some of the most militant American popular music of the 20th century. Its stars described, in detail, the tough working conditions drivers endured, and they portrayed police, rightfully, as an enemy of the working class. Only rap music—and perhaps the Tejano corridos of the bracero era—has more consistently cast cops as villains.

Trucker country crossed over into the mainstream in the mid-to-late 1970s, just as the United States’ crude oil imports were hitting their first peak. The gusher, so to speak, was C. W. McCall’s “Convoy,” a Number One hit about a coalition of radical drivers (joined by a few hippies) who complete a cross-country trip despite being pursued by “smokies” (cops), “a bear in the air” (a cop with a helicopter) and the Illinois National Guard. In “Convoy,” truckers discover the power that comes when they, too, halt the flow of goods. But as truckers, they also go further, creating a utopian trucker community in the flow itself.

For the drivers of “Convoy,” liberation comes not when workers receive better wages, or better representation, but when they take control of the means of circulation, driving their trucks wherever and however they please. With the drivers in charge, circulation is decoupled from commodity exchange, becoming instead a site of mobile, international, working-class solidarity. A less-popular sequel song, “Around the World With a Rubber Duck,” even continues the story with the convoy crossing the Atlantic Ocean and continuing on to Soviet Russia.

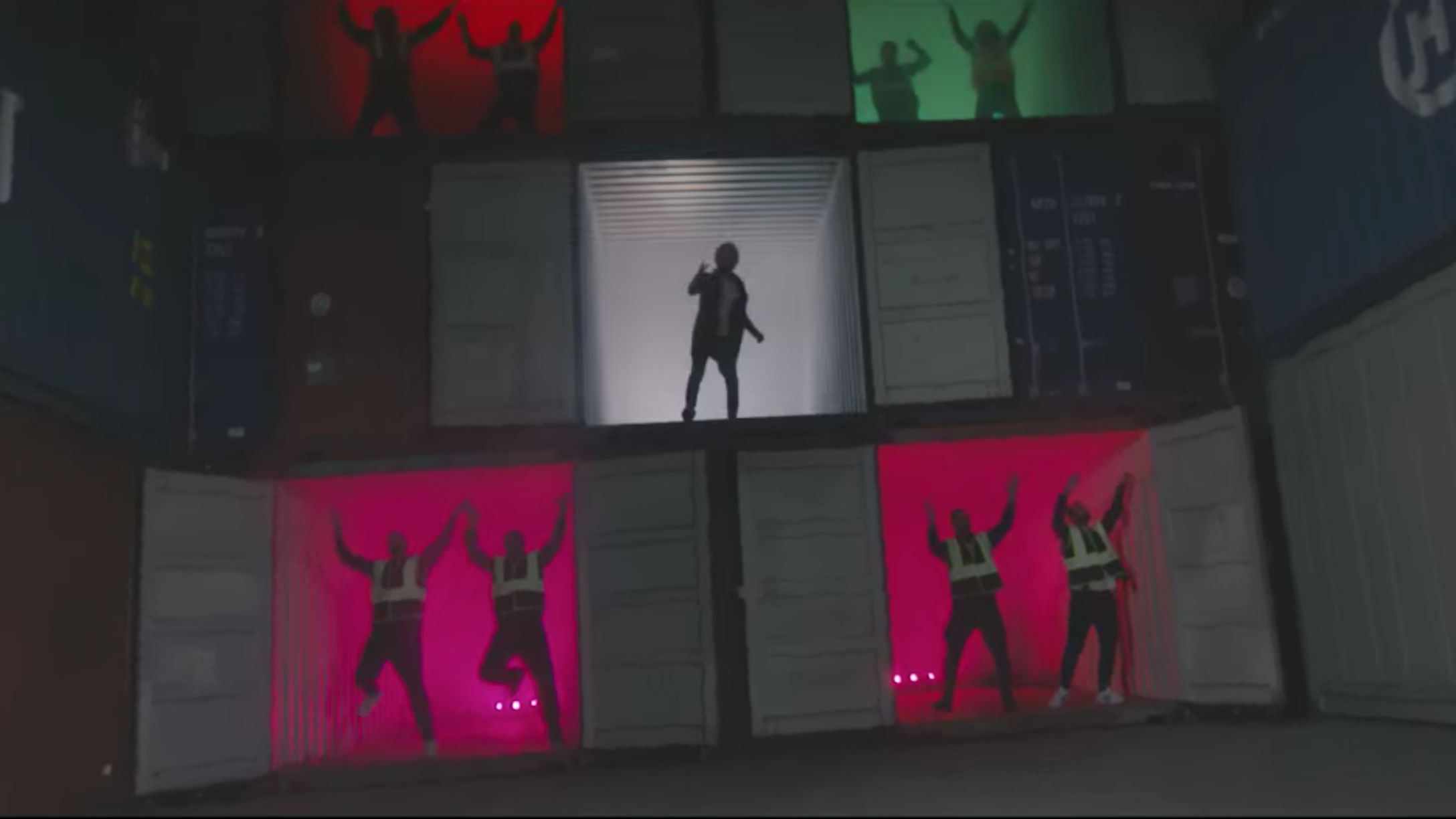

Yet before McCall’s dream could become reality, the entire shipping industry—itself absorbed into what’s called the logistics industry—was reconfigured. After the Vietnam War, technology like the intermodal shipping container was adapted for commercial use, undermining the power of dockworkers to close ports and truck unions to shut down nodes where cargo was once repackaged and transferred. (Today, music videos like Ranjit Bawa’s “Truckan Wale” and Nishawn Bhullar’s “Pakke Truckan Wale,” reimagine these containers as mobile discotheques for choreographed dances.)

Labor faced another defeat when deregulation under the Carter and Reagan administrations broke the back of the Teamsters union. The 1980 Motor Carrier Act was particularly effective, pushing more drivers to become independent contractors—owner-operators like the cousin in “Yaad Yaar Di.” The effect was devastating. From 1977 to 1987, long-distance truckers’ total employee compensation per mile dropped 44 percent, and unionization fell at a similar rate.

In American country music, this period saw the waning of the trucker fad. By the early 1980s, the moment of “Convoy” had given way to the era of Urban Cowboy, the genre’s lens turned toward cities and away from the interstates that connected them. In the Northern India, however, a new truck driving music was emerging in the cabs and rest stops of Punjab. The key, says musicologist Peter Manuel, was cassettes. In his book Cassette Culture, Manuel writes that as Punjabi truckers purchased and exchanged tapes, they developed a new repertoire of songs associated with the profession. These songs were filled with innuendo and often considered offensive by bourgeoisie. Their most famous singer was Amar Singh Chamkila, who recorded tracks like “Driver Rok Ghari” with his wife Amarjot before both were murdered by gunmen on motorcycles in 1988.

According to Gurinder Singh Khalsa, the head of SikhsPAC, Sikh immigrants began to enter the North American trucking industry at around this time. The catalyst, he says, speaking from his home near Sacramento, was the anti-Sikh violence that followed the assassination on Indira Gandhi, pushing many people out of India. On a new continent, Sikh men became truck drivers because it was one of the few jobs they could perform without removing their turbans.

Steve Viscelli, the author of The Big Rig: Trucking and the Decline of the American Dream, picks up that story in the 2000s, which is when he believes that Sikh and Punjabi drivers began to enter the industry en masse. Until the early 2000s, he tells me, American drivers had mostly been white and black men. The decline of wages and working conditions, however, meant that these recent drivers left the industry more quickly than did the drivers of the 1960s and 1970s. My grandfather, for instance, stayed on the road for decades. Today, annual turnover at large companies can exceed 100 percent—something the government encourages when it funds training programs designed to hurry new drivers through the door.

About 15 years ago, these companies increased their efforts to recruit immigrants. Workers came—and continue to come—from Asia, Eastern Europe and Mexico. The goal is to find workers with few local commitments who are looking to make as much money as they can over a short period of time, even if it means living in the cab of their truck—an experience depicted in music videos where teams of two drivers trade shifts behind the wheel. Much like mineworkers recruited from similar places over a century ago, these drivers often use their shared ethnicity and community networks rooted in their old homes to build present-day mutual aid societies, helping each other protect jobs at certain companies and manage the difficulty of life across borders. Online, Punjabi trucker Facebook groups have become another venue for organizing, as well as communicating and sharing music.

Sardool Sikander and Amar Noorie were among the first artists to depict Punjabi truck drivers outside of Punjab, as immigrants, in the United States and Canada. In Punjab, they were Chamkila’s contemporaries. Both were born to musical families in Eastern Punjab, between Chandigarh and Ludhiana, and in the mid 1980s, they became duet partners, eventually marrying. Their records occasionally discussed trucking—”Aa Gaya Mercery Truck Ni,” from 1995, stands out—and Sikander contributed music to the 1997 Punjabi film Truck Driver, but they didn’t touch the subject on a single until they released “Truck” in the 2000s. On this recent record, Sikander describes fixing up his vehicle and buying a box of barfi, a South Asian dessert, for his sister-in-law. In the video, the husband shows his wife, played by Noorie, a new 18-wheeler, which he parks outside their house—a house located not in their native Punjab but rather a suburb somewhere outside Toronto.

Today, there are dozens of songs that tell these stories. In “Truck on the Highway,” its music video set in Chicago, Sony Nathowalia brags that he never changes his route, even when the conditions are dangerous. He describes a ritual that he repeats every journey: when the truck is in first gear, he says a prayer; in second gear, he recalls his lover; and in third gear, he plays some Chamkila in his cab. In “Akh Baaz Vargi,” mentioned above, Dalbir Bhangu describes a similar routine: Gurbaani—a sort of SIkh hymn—in the morning and Chamkila for rest of the day.

These Punjabi records, like their country music counterparts, are often explicit about the difficulty of this work. Jass Bajwa’s “16 Ghante,” for instance, is named for the number of hours its protagonist drives every day. Bajwa lists some of the hazards truckers face—slippery roads, stops by officers from Canada’s Ministry of Transportation—and decides that he’ll only drive in North America for three more years, saving up his money to return home. “Truckan Wale,” by Ranjit Bawa, is even more critical, describing the back pain that comes from driving routes that last 20 days—so much driving that the lines on his palm have begun to fade away. It’s telling that this journey is more than three times longer than the one described by Dave Dudley in his 1963 country hit “Six Days on the Road.” “Unjh kaun karda ae gall hunn hakkan di,” Bawa sings. These days, nobody talks about anyone’s rights.

One can draw a similar conclusion from the music video to “Tralle” by Anmol Gagan Maan, one of the few female singers to describe life inside the logistics industry. (The best known trucker song by a woman in the country music tradition is likely “Eighteen Wheels and a Dozen Roses” by Kathy Mattea.) Maan’s clip opens with a pair of racist white cops pulling over an Indian driver. “Whose truck is this?” they ask. The driver says that he owns it himself, but they don’t believe him, demanding that he take them to his company. The cops relent only because the lot is filled with dancers, led by Maan, who then hosts a party for drivers at her mansion in the Hollywood Hills.

As a fan of American country music, I wanted to learn how the new trucker songs related to older ones—what continuities, and what differences, might exist. Over a month and a half, I contacted as many of the contemporary singers and songwriters as I could find, but of those that got back to me, none saw a direct connection—or even knew that a body of American trucker songs had ever existed.

Khalsa is the only person who thinks there might be a link. For him, it comes back to the nature of the job. “If I’m a doctor, I don’t have time to listen to music,” he says. “Truck drivers do. They need entertainment.”

Some of the best trucker country songs don’t just provide this entertainment, they also offer a sort of meta-commentary about the very need for it that Khalsa describes. “Truck Drivin’ Man,” first released in 1954, relates the joy a trucker feels when he pulls into a rest stop and hears a great song about trucking over the jukebox—in fact, the song “Truck Drivin’ Man” itself. Mass culture is the cause of his isolation, forcing him to haul commodities across the country, yet it also, in moments like this, can confront him, at a rest stop off a random road, with an aesthetic experience that’s both unexpected and sublime, a moment of connection sparked by a song that is itself a commodity.

Still, even if there is no direct link between the old country trucker songs and the new Punjabi ones, there remains an undeniable proximity.

“Truck Drivin’ Man” was probably the most recorded tune in the trucker country canon, and its most famous version may be the one cut by Buck Owens, a singer hailing from Bakersfield, California. If Texas was the place where trucker country was born, then by the 1960s, Bakersfield, another oil town, had become its de facto capital. Bakersfield resident Red Simpson was probably genre’s biggest star. Simpson got so deep into the trucking scene that he released a record called “I’m a Truck,” sung from the perspective of the vehicle itself. Owens, who was one of the biggest stars in country music as a whole, did enough truck material that he’s usually listed among the genre’s key artists. Merle Haggard, the biggest name from the following generation of Bakersfield acts, eventually added “White Line Fever” to the trucker repertoire.

Today, a new Bakersfield exists side-by-side with the old one. Now if you drive through the city, you can hear not only the country music of Owens but new Indian hits on Punjabi Radio USA, which broadcasts from a tower in the city. The openness of Punjabi Radio USA’s format recalls the way radio was run before most stations were controlled by a handful of corporations. Instead of tight, algorithmic playlists, they air an afternoon request show that runs from 12:30 to 2 o’clock. The rest of the day goes back and forth between news and music. “If truck drivers wanted to listen only to music they would listen on their phones.” Balwinder Khalsa, the station’s manager, tells me. “We need to give them everything.”

For Punjabi Radio USA, this means information about job openings at shipping companies and news specific to the logistics industry. The station even has a phone line that drivers can call if they have a question about a certain policy or regulation.

Last year, Punjabi Radio USA became an important source of information in the implementation of—and fight against—electronic logging devices, also known as ELDs. In the old days, drivers logged their hours in paper notebooks. These logs occasionally show up in the lyrics of songs like “Six Days on the Road” and music videos like Gurnam Bhullar’s “Drivery.” Since the introduction of the intermodal shipping container, however, logistics have become more flexible than ever, moving asymptotically toward a “continuous flow” of goods across the supply chain. For “supply-chain managers,” the goal is to create systems of circulation whereby cargo spends as little time as possible in warehouses and docks, or even on the grocery store shelf. Companies like Walmart and Amazon use “radio frequency identification” (a technology first implemented during U.S. military campaigns in the Middle East) to facilitate “cross docking,” a method whereby incoming product is moved directly into outbound vehicles, bypassing traditional storage. Dell requires that its suppliers hold onto computer parts until the very day—even the very hour—that they are needed for assembly.

This puts new pressure on the truck driver. The new system, known as “Just in Time” inventory management, means that many long-haul drivers no longer travel set routes, instead being sent around the country and across borders, as flows of capital demand. The ELD adds a new form of employee surveillance to that process, creating a record of where and when a driver moves. On the surface, they have a useful function: to limit drivers to 14 hours of work per day. One problem, however, is that the count doesn’t match road hours—it continues logging, for instance, even if a driver is resting while their cargo is loaded in or out. Beyond that, the problem with ELDs is its effect on the way drivers are compensated. Long-haul drivers are typically paid per route, not per hour, which pushes them to work beyond the point of safety in order to make a living wage.

When the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration announced that ELDs would become mandatory, Sikh drivers were hit particularly hard. Stations like Punjabi Radio USA covered the issue for months. Punjabi drivers helped organize a campaign called Operation Black and Blue to protest, and in October of 2017, in downtown Bakersfield—about two miles east of Buck Owens’s signature music venue, the Crystal Palace—they led a large rally to speak out against the new rules.

In Northern California, meanwhile, drivers expressed their anger through a technique that will be familiar to fans of old-school trucker country: the convoy. Traveling from a Sikh temple in Yuba City to the capitol in Sacramento, drivers occupied three lanes of Highway 99 and, as they neared their destination, began to drive well below speed limit. One estimate put the number of participating trucks at 700, and footage was later uploaded to YouTube by a user named Bobby Jathol. For the soundtrack, Jathol choose not C.W. McCall but Sherry Mann’s “Transportiye.” A different user, Dill De Gall TV, supported the protests by uploading an a cappella song called “Trucker’s Rights.”

Operation Black and Blue didn’t overturn the new rule on ELDs, but it still stands as an impressive display of both organization and force. The drivers demonstrated the kind of power that comes with being able to halt, or even slow, the circulation of energy and goods, particularly in the age of Just in Time inventory. In another video from the convoy, a pair of cops write tickets to to a group of protesting drivers. “You guys can’t be what doing what you’re doing,” one officer tells them. “A freeway is not a place for protest.” The drivers know otherwise.