Bismillah is a Pakistani restaurant in Baltimore that serves a cheap buffet all day long. I have only ever seen men eat here, many of whom I have come to recognize. I have gotten used to the buffet, too, which tastes the same every day. Every day, it tastes like leftovers from yesterday. I have never seen anyone order entrees here. Except for me. On days when I have the time, the money, and, most importantly, when I am missing home, I walk to Bismillah and place an order from the menu: a kadhai chicken and an extra naan. I have slowly come to know the man who takes my order. Or at least I have come to know that he left his home in Lahore thirty-five years ago.

My paternal grandfather was born in Lahore in 1909 and grew up and studied there. When the young revolutionary Bhagat Singh was imprisoned in the Borstal Jail, my grandfather would regularly visit him. Along with other student comrades, he signed a blood pact promising to liberate Bhagat Singh from the jail. I wonder if my grandfather ever met Agyeya, the poet-scholar now widely known for having initiated prayogvad, the movement of formal experimentalism in Hindi poetry. Around that same time, Agyeya was studying in Lahore, and, with older revolutionaries, was plotting Bhagat Singh’s escape. They devised a plan to attack the Borstal Jail’s gate on the day when Bhagat Singh was to be taken out for legal consultation. This attack, however, was sabotaged and the revolutionaries were forced to leave Lahore immediately.

Agyeya followed his comrades to Delhi, where he started working in a factory called Himalayan Toilets. The factory was only a facade. Inside the building, Agyeya (or the scientist, as he was known in those circles) had been making bombs for the anticolonial struggle, which began to intensify after Bhagat Singh was hanged in 1931.

Years later, my grandfather was also forced to leave Lahore, but in different circumstances. He fled the city during Partition, when the Indian subcontinent was divided into a Hindu-majority India and a Muslim-majority Pakistan. Having barely escaped the carnage, he arrived with his family in the newly formed state of India. He began his new life in the city of Amritsar by becoming an active member of the RSS, a Hindu rightwing paramilitary organization of volunteers.

Recently, I was waiting for my kadhai chicken and the extra naan when a South Asian (presumably Pakistani) man was on his way out. He salaamed me and I returned his greeting. Two black Muslims were sitting next to me. One of them immediately stopped eating, slammed the table with his fist, looked me in the eye and said: “To them, we are just Muslim n****s!” He was quiet for a while, and ate his lunch, and I ate mine, but as he walked out, he pontificated loudly on Islam’s anti-racist foundations. The restaurant was empty.

I was aghast. My neighbors were, clearly, both Muslim. They were wearing the distinct physical markers—skull caps, beards, kurtas and ankle-length pajamas. I, on the other hand, am not a Muslim. I was only a bearded brown man. And yet, this stranger had chosen to greet me with as-salaam-alaykum while completely shutting out his fellow Muslims.

Before coming to Baltimore, I lived in New Delhi for seven years, where my beard often gave me problems. I noticed that the number of pat-downs I got from the CISF jawans stationed at the entry gates of the Delhi Metro were in direct proportion to the combined length of my kurta and my beard. I still remember the night when the party promising neoliberal death and religious pogroms singlehandedly won the national elections. Somebody in the street shouted at me and my friend: “ab se mulleh khatre mein hain” (“from now on, the mullahs are in danger”). The word mullah is a neutral term when used for Muslim clergy, but here, it had a pejorative connotation. I started shaving and trimming my beard more regularly.

Though they would probably never admit to agreeing on anything if they were to meet, the Hindu fascist in New Delhi and the diasporic Muslim in Baltimore had made the same assumption. Both had taken my beard to be a sign of Muslim identity. In turn, each had expressed the desire which this sign evoked in them. The Hindu fascist desires an annihilation of the Muslim Other. He believes that somehow it will alleviate the politico-economic, sociocultural and religious distress which he may or may not be suffering from. On the other hand, the Pakistani (presumably) Muslim’s reaction to my beard expressed solidarity in a diasporic setting. And yet, this solidarity was racially suspect. In me—a non-Muslim, born into a Hindu family—he believed he had found a fellow Muslim from South Asia. But while sharing the intimate greeting with me, he had also ignored the two black Muslims sitting nearby.

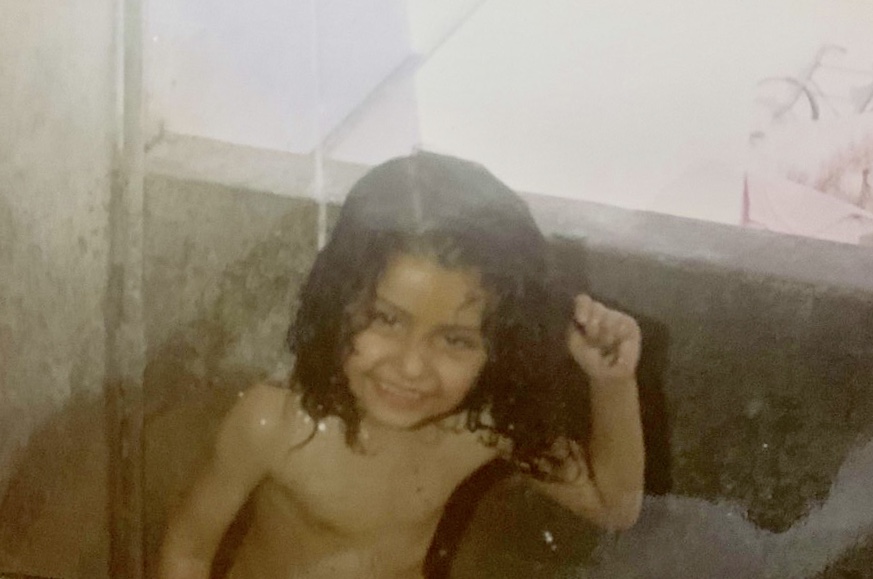

I felt stranded, unable to clear a way through the perilous thicket of identities. Suddenly, I was struck by a childhood memory: my mother, along with my brother and me, kneeling in a mosque, amidst a small congregation of Muslim men. While imitating the Islamic prayer movements, my mother kept whispering—I clearly remember—a Hindu mantra. I could hear her whispers; I remember being mortified.

We were newly arrived in the northwestern Indian state of Rajasthan, to a small town called Lakheri, where the cement factory my father worked for had temporarily transferred him. I remember very little of him from this period, aside from the fact that he was specializing in becoming an underpaid workaholic. On an evening walk with my mother, who was used to being alone with us, we came upon a mosque and she decided to wander in. I had never seen a mosque before. I was around nine years old, and visiting from my home in Barmana, a small factory town located in the lower-middle ranges of the Himalayas. There were around seven or eight men in the mosque, each engrossed in prayer. We all joined them, and started performing the namaz by imitating their style of kneeling and bowing. Although no one had objected to our entering the mosque and joining the prayers, I, having grown up in a family of Hindu nationalists, was worried that our presence, especially that of my mother, might not be welcome. Still, I followed my mother and repeated the cycles of kneeling and bowing with a somewhat mechanical regularity, not knowing what words I should utter. My mother, on the other hand, kept murmuring the mahamrityunjaya mantra, a verse from the Rigveda, with an unwavering piety and reverence. The inexplicable ease with which she grafted her Hindu religious beliefs onto this Islamic ritual bewildered me to no end.

After the namaz was over, everyone greeted us pleasantly. I was quite surprised by their congeniality towards us. My mother got talking to some of the men while my brother and I walked around looking at the austere interiors, wholly unlike the familiar ornamental excesses of Hindu temples. By the time the conversation ended, we realized that our mother had enrolled both of us in the madrassa to learn the Arabic language.

Today, this memory seems like a fantasy. Given the relentless violence being unleashed against Muslims in India, it is inconceivable that a Hindu family would send its sons to study in the “dens of jihadism.” The fact that our own grandfather was a Hindu nationalist makes my mother’s decision all the more perplexing.

Why did my mother decide to casually enter the mosque and join the praying men, in such a bewildering gesture of religious and affective solidarity? As if that wasn’t enough, why did she decide to enroll her Hindu sons in the madrassa? More importantly, why had I forgotten these memories? And finally, why was this memory suddenly triggered by the incident at Bismillah?

At this point, some of my friends would doubtless interject with their armchair psychoanalysis: The magnificent oils and spices of Bismillah must have lubricated my psyche enough to dull its defenses, allowing my repressed memories to manifest. Whatever, nerds. No wonder I always go to Bismillah alone.

It’s likely that in entering the mosque, joining the praying men and enrolling her sons in the madrassa, my mother had intended to alter the course of my life to come in a Hindu nationalist family. But at the time, I didn’t take in the lesson. I spent my teens idealizing nationalist brotherhoods, while trying to imbibe the legacy of my grandfather. I spent my twenties trying to negate these choices by seeking the comradeship of male intellectuals in Marxist circles. It took me nearly two decades to be able to catch up with my mother, to realize that things were, indeed, complicated, that the society I lived in had always been riven along the lines of religion, and that neither religious fundamentalism nor Marxist demystification would ever resolve these contradictions.

For the next two months at the madrassa, my brother was the better student, and the maulvi (an honorific title given to Muslim religious scholars in South Asia) adored him. I found out that many other students were there to learn Arabic in order to be able to read the Qur’an. I had no clue as to why were we were learning it, but our camaraderie with the other students kept us going. The older boys would spend their time learning to recite the Qur’an with an appropriate sense of submission and reverence. The boys and girls of our age group were less responsible. They would often bunk classes, only to be punished by the maulvi on the next day. The maulvi would repeatedly remind us to behave properly, for we were, as he would put it, in the divine presence of God. I cannot remember if I felt any sense of awe or piety while learning the Arabic alphabet. But, inhabiting the madrassa’s everyday life, I must have absorbed at least some Islamic cultural and religious sensibilities.

My only regret is that our summer holidays ended too soon. And because of some last minute changes in our travel schedule, I couldn’t even say goodbye to anyone at the madrassa. We had to just disappear overnight. On our way back to Barmana, we stopped to visit Mehendipur Balaji, a Hindu temple famous for its ritual healings and exorcisms. I vividly remember how people possessed with bhut-pret (ghosts and spirits) had filled the courtyard outside the temple. Some of them were dozing off, some others were shaking, shouting and spitting curses. They were waiting for their peshi (“a hearing”) at Balaji’s darbar (court). These two terms have their origins in the Arabic and the Persian. But they have been folded into the Hindu devotional lexicon, even if they make it seem as though Hindu rituals of exorcism are performed at an Islamic court of law.

The next day, our parents wanted to perform our mundan ceremony, a ritual shaving of the head. In the Hindu cosmos, mundan is generally taken to signify freedom from the past life—here, associated with the hair which a child is born with—and his initiation into the future. My parents found a man who claimed to be an expert in these matters. As it turned out, however, he did not know how to cut hair, much less to shave a head. He asked us to wait near the courtyard, and turned up ten minutes later. The Brahman pandit, who should have accompanied him as part of the ritual, was conspicuously absent. This man spent about fifteen minutes trying to operate a pair of scissors. Then, he just left, leaving us with uneven patches on our heads. Our parents somehow thought this was fine. They tried to rationalize that maybe this is what the ritual of mundan meant in these parts. Both my brother and I nodded in agreement with them. The possibility that we might have been swindled by a small-time con man never occurred to any of us.

We travelled back to Barmana, and returned to school the next day, not even slightly conscious of the grotesque condition of our hair. Our friends at school lampooned us to no end. In addition, we even suffered a severe reprimand from an Arya Samaji (Hindu Reformist) teacher, who was particularly scandalized by our haircuts, and refused to believe that the otherworldly form of both of our heads was the result of a mundan ceremony.

The mundan was supposed to inscribe my Hindu religious and upper-caste identity into my body. But the act remained incomplete. The memory of this incompleteness, as well as the memory of being an incomplete Muslim in the madrassa at Lakheri, often makes me anxious. These experiences, however, are not mine alone. They seem to me to reflect a more general crisis of religion in South Asia.

The understanding of religion as a distinct social community was first introduced by the decennial census of 1871. The British colonial administration, aided by native elites, had set about systematizing the myriad flux of sacred and profane practices, concepts and sensibilities into discrete “religions.” Similarly, the officially commissioned translations of sacred scriptures into English were undergirded by the demand for the “true religion,” that is, Christian monotheism. It was not long before these processes led to the construction of the monotheistic “Others” of Christianity—Hinduism, as distinct from Islam, Sikhism, as distinct from Hinduism, and so on.

At the time of the Partition, the Indian nation-state came to inherit this condition. It tried to resolve its difficulties by conceiving a distinctively Indian ideology of secularism, which prescribed equal respect for all religious identities. However, instead of dismantling the legacy of colonial oppression that had imposed these rigid religious formations, the constitutional policy of secularism ended up preserving and reinforcing the stark distinctions between religious identities.

The progressive worsening of the Indian economy over the past three decades has further intensified the debilitating effects of this colonial legacy. The rate of unemployment in the country reached a record 7.4 percent in December 2018. More importantly, 81 percent of the employed workers in India are currently toiling away in the underpaid and unprotected markets of informal economy. Against the background of this generalized social precarity, the RSS-led Hindu right wing has succeeded in mobilizing a massive social base, which has worked both to abuse the civic freedoms of the institutions of Indian democracy, and to normalize a vicious culture of Islamophobia in the public sphere. Indeed, the popular fascist cliche of everyday political life in India explains the Muslim presence in our country as an unfinished business of the Partition. Moreover, in the last five years, this right-wing base has also provided for a standing reserve army of fascist Hindu militants, who, backed by the BJP government, have committed numerous lynchings and pogroms against the Muslims and other religious and caste minorities.

In the wake of the ongoing religious violence, several critiques of religion have emerged in India. Many experts have come to distrust the explicit presence of religion in the public sphere, calling into question the ability of religiously minded people to engage in rational debates. Others claim that religion itself is only a remnant of pre-modern times, and that religious violence would end as soon as the masses are demystified. Very few, however, seem interested in analyzing what is singular about the notion of religion in India, and how, on an everyday basis, it continually unsettles the frontiers between public sphere and private lives, between the sacred and the profane, between institutionalized religiosity and the so-called folk practices, and most significantly, between the “religions” themselves.

What will be the future of our religious pasts in India? Is religion an illusory obfuscation of what is real and historical? Or is religion a complex of beliefs, sensibilities, concepts and practices, which—even though some may dismiss them as fetishes, mysticisms, superstitions, and so on—can, and in fact, do determine the possibilities and limits of our collective future?

I spent that July evening in 1997 at our local barber shop, the only one we had in our village. Come to think of it now, the barber could have simply shaved my head. But instead, he diligently spent a long time reconstructing my hair, trying to return it to the shape and form it was in when I had last visited him, two months ago, before we prepared to travel to Lakheri.

Aditya Bahl