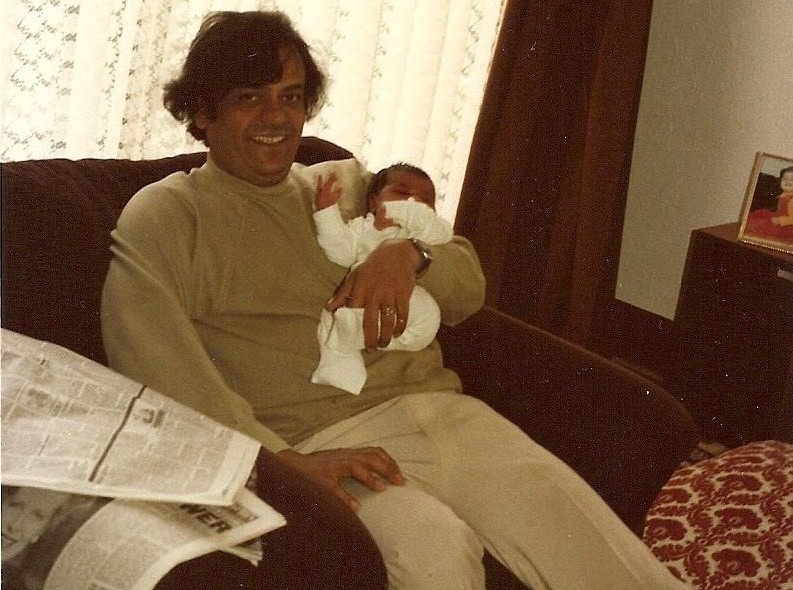

That’s my dad holding me in our living room, after my parents brought me home from the hospital. It’s early May 1983: Can you see Margaret Thatcher peeking out from the newspaper? The word “power” rounding out the headline? A month later, she would win a second landslide election victory.

Rustling newspaper was the soundtrack to so many of my childhood memories of my dad, the best kind of news, he’d say, as long as it wasn’t a Murdoch paper. It was superior to broadcast because you could get deep into it, memorize the details to arm yourself for your next big political debate. He cared about this stuff, and he wanted me to care too.

When this photo was taken, he can’t have hated her that much yet. She wasn’t very popular during her first term, so who could’ve guessed that she’d remain in power for seven more years? As a doctor, he must’ve known that the Griffiths Report was underway, but the effect it would have on the NHS wouldn’t be felt until the late 80s. Judging from the amount of milk my parents made me glug down as a kid, he probably didn’t love the “Thatcher, Thatcher, Milk-Snatcher” stuff either. But it was the dad I knew later in life was the kind of person who would’ve completely understood the thinking behind the Thatchcard, if he’d heard of it.

But the man in that picture, holding me a day or two after my birth? The hate has yet to set in for him. In fact, in the years to come, he would acknowledge what an achievement it was that a woman had become the Prime Minister of Great Britain without being the wife, daughter or sister of a former leader (which happens a lot in south east Asia, where he grew up). He could admire the achievement, but grow to despise what she became during her many years in office. He wouldn’t be the only one.

In the years after that photo was taken, hating Margaret Thatcher became a British national sport. As a Labour voter–and an NHS worker who moved halfway across the world to work for the idealistic health service when it was young–my dad would take to this sport like he had done to cricket and football. But did he make it so personal, like Thatcher was specifically his nemesis, looking to destroy everything he held dear?

The eighties were a long time ago, now; that picture wasn’t even taken forty years after the end of the Second World War, when the creation of the welfare state–and the NHS in 1948–coincided with decolonisation of the British Empire. Former subjects of the Empire had left the ex-colonies and moved to work for the welfare state, as my parents did; the moment defined the Britain they had come to live in, the country where they would have children. But then the money ran out in the seventies, culminating in the 1978-9 Winter of Discontent; when the sitting Labour government was bulldozed, there was no one but the Tories: in a two-party system, one party’s downfall means the public votes for the other, and what else were the Tories going to do but cut, cut, cut? That’s what they’ve always done. It’s their thing. And so, Thatcher presided over the destruction of the welfare state.

Her rule changed how my father’s generation saw themselves, and they didn’t like what they saw. I suppose the right is having that same kind of moment now, with Brexit. Notice how the coverage treats Theresa May, our second female PM: she’s getting the blame for someone else’s mess. Firstly, it was David Cameron who called this darn referendum, then promptly resigned and disappeared, humming a little tune while he left. Secondly, Euroscepticism is baked into the Conservative party’s DNA; Cameron tried to appease the more extreme wing of his party by calling the vote on EU membership, and look where we are now.

But no, let’s have a go at Theresa May like she started all this, let’s force her to dance onstage in front of her own party, and cement the idea that female leaders are cold and robotic and there to pin crises on.

Back to Thatcher, though. In the 70s and 80s, it would have been easier to focus on her, the rising star, than on the economic and global forces outside of her control. The 1976 bailout from the International Monetary Fund enforced public spending cuts on the Labour government, the first time that UK domestic policy was determined by a non-UK authority. When the 1979 election saw the Tories voted in, they took the opportunity to roll back state spending even further, because that’s what right-wing parties do.

Was Margaret Thatcher hard to like? The person? We can only really know her image. She was the first woman in her position, so she was supposed to be better than the men before her; she was supposed to be more nurturing, providing milk rather than snatching it. But if she compared running the economy to handling a household budget, she made it clear that she was not part of the sisterhood (“I owe nothing to women’s lib,” she said in her first term in office). I’ve been re-watching Veep recently, and Selina Meyer’s “flawed feminism” can’t be too far off the mark (though Meyer tries to remain young and sexy, and Thatcher went for a stern governess vibe right off the bat, much more British). It’s still not easy to be a woman in the public eye, let alone a female politician. What you wear will get more coverage than your voting record.

So, why all the Thatcher-hate? Why was she the only person to make my dad’s nemesis-list? It’s easier to hate a person–especially one with such a grim public image–than to understand the global forces winding and unwinding around you. I can cast a more dispassionate eye from decades’ remove, but I can also imagine living through it. The miners’ strike and the Poll Tax riots and the beginning of the treatment of the NHS as a cash-draining public service, rather than a monument to the best of socialism…

The dream died so quickly. There was so much anger in need of a target.

After Thatcher’s own party pushed her to resign in 1990, she haunted British politics until Tony Blair’s huge victory in 1997, which of course became a disappointment in time. But while Thatcher’s name was still taken in vain in my house–and all sorts of problems were laid at her door–she was spoken of in the past tense, no matter how present she felt. She could do no more harm.

In 2001, I ended up going to the Oxford college where Thatcher had taken her Chemistry degree, Somerville. Because of her cuts to university funding, the university had famously denied her the honorary degree it has always given to Oxford-educated Prime Ministers. “A banner was slung across Somerville, the Prime Minister’s old college, saying ‘No degree for Mrs Thatcher.’”

It wasn’t surprising; it’s always been a left-wing college, faintly embarrassed by its most famous old girl. But like my dad, Somerville seems to have conflicted feelings about Thatcher, because there are so many to have about her. When she died in April 2013, the principal sent out this alumni email:

“This has been an important week for Somerville – the death of our most famous former student has shone a spotlight on the College and sparked new conversations on its relationship with Margaret Thatcher. We had a variety of responses from alumni to our statements online: some expressing sadness at the news, others stating their absolute opposition to her policies and political legacy.”

It was impossible not to smile at these opening lines, and remember how my dad oscillated between beaming with pride at my admission to Oxford and then frowning (slightly) at the thought of my college’s “most famous former student.”

The email goes on: “Margaret Thatcher is a true alumna of the college. She came from a background without social or financial advantage. Thanks in part to her Somerville education, she went on to achieve the pinnacle of power and political success. Winning no fewer than three general elections, she became Britain’s longest serving prime minister in the twentieth century. She had an enormous impact not just on this country, but on the international political stage.”

A woman with power when few women had it, and a national leader stamping her party’s policies onto the country; she became the hateable face of that period of change, and even upset the institution that made her.

But I can’t detect enough of a person in all the swirl of stories to hate. There’s just the idea of her now, the fact that she forced this future to happen to Britain. But I think capitalism would have worked its way into the bones of this finished empire somehow, anyway. That it was Thatcher who took away the milk just made it an easier story to tell.

Suchandrika Chakrabarti