The Eternal Derby, vechno derbi in Bulgarian, is just a football game to most: Levski versus CSKA. The two teams are known as Bulgaria’s fiercest, and their head-to-head battles are legendarily—sometimes even literally—explosive. During a match last year, a hooligan threw a bomb that blasted a female police officer in the eye and made headlines worldwide.

When I attended my first game, I was teaching English at a local high school in Sofia, Bulgaria’s capital city, while on a Fulbright fellowship. Bulgaria’s rich folkloric traditions, and its undefined state between communism and westernized democracy, intrigued me, and I applied for a grant. A year and many Skype calls later, I found myself traveling around the country, working on a book and, for at least twenty hours a week, teaching English to hundreds of high schoolers.

Every time I walked into a classroom I encountered something other than what I had prepared for in my lesson plans. Once, I found a roomful of eighth graders gyrating to the Bulgarian folk-pop music known as, “Chalga” while projecting, at full blast on the whiteboard, a music video that most definitely should not be seen in an eighth grade classroom. Another time I arrived for my lesson seconds before a student would have hurled a wooden desk chair across the room at one of his classmates. Luckily that didn’t happen; instead he threw a backpack out the window.

While my classrooms weren’t always volcanic pits, there were certain things I could never go a day without hearing. Among them, Bulgarian nationalistic pride, and the rivalry between the infamous Bulgarian football teams, Levski and CSKA.

The scope of these outbursts varied wildly. Sometimes a student felt it necessary to stand up, fist in the air, and say, “Macedonia is Bulgaria!’ Admittedly this was quite a common thing to hear from adults as well. The tumultuous conflicts arising from disputed questions of borders and statehood in the Balkan states are nothing if not well documented. Most recently this issue was brought up on the international stage with respect to Macedonia, when Greece was bargaining with the former Yugoslav Republic on their name change.

Sometimes a student might stay after class to teach me about ancient Bulgarian kings, or to talk about how Bulgaria should modernize and catch up with the rest of Western Europe. Shocked with my knowledge of the language, students reacted with the utmost joy when I would interject in Bulgarian, or write in Cyrillic on the board. They spoke with real reverence about their nation and its history. One of my most successful lessons was having the students group up and present to me a specific thing which they thought represented Bulgaria. Contrary to almost every other lesson I taught, not a single person complained.

The same went for the football teams. During a lesson with a particularly rowdy ninth grade class, one young man started pounding his fists on the desk chanting, “CSKA, CSKA, CSKA”. Meanwhile a fan of Levski, the opposing team, marched across the room to yell in his face, “SAMO LEVSKI” (“only Levski”). After class the same students crowded around my desk asking me whether I liked football, and if I did like a Bulgarian team, which one would it be? Levski, blue, or CSKA, red? I indulged them when it came to talking about Bulgarian history or what they thought of Bulgaria’s future, but the football controversy was one I didn’t want to get myself involved in—at least, not in the classroom.

But outside the classroom, away from my students’ view, I became slightly obsessed with these two aspects of Bulgarian society, red and blue. The dichotomy came to symbolize, for me, their reverence for the past clashing with concern for their culture’s place in a future modernization alongside that of Western Europe, played out in the extremist mentality that characterizes sports culture everywhere in the world. As these two topics were constantly recurring in my Bulgarian life, I felt they were analogous to each other in some specific way, and I wanted to find out exactly how.

It was spring and the football season was closing in on the final rounds. The air buzzed with whispers of the two teams and almost everywhere in the capital you were bound to see just a bit more blue or red, depending on the neighborhood. Hooligans from one team or the other seem to control particular sections of Sofia. The graffiti on the walls can be a clue: Which team’s graffiti you might chance to see, or which color graffiti has a line through it in another color.

I got caught up in the excitement, and decided that the best way to fill in my analogy would be to attend a Levski versus CSKA game myself.

I bought two tickets to the Eternal Derby, and now it was I who was excited to talk to my students about football. The next time I had class with my rowdiest set of hooligans, I waited until the end, called the boys over and laid down my two tickets for the game. Wild howls broke out around me. Cheers rang out and fists flew in the air: “MS.! YOU’RE GOING!” For some, the cheers quickly turned into serious concern for my safety and questions regarding which team I was supporting. “Ms. it’s very dangerous to go alone. You can sit with me if you want. But you must be careful.”

Dimitar grabbed my tickets and to his disappointment, found out that I’d bought seats to sit on the Levski side, the blue side. “Ms. how could you?” he whined. I defended my ignorance of either team and asked them, please, to clearly make their cases for whom I should cheer. This was my genius trick to not only get them to speak English, but also to reveal a bit more history about the controversy for my personal research.

Everyone was ready to throw in their two cents, even a couple of the straggling girls who’d stood around to listen. The history of the two teams was explained to me by the obvious choice of historians; ninth grade Bulgarian boys. They huffed out their words, beat their hands over their chests, and pushed each other out of the way in order to stand in front of me and lay down their cherished beliefs.

In 1914 Levski Sofia was one of the first established teams in the history of Bulgarian football; the game had been introduced to the country only about twenty years before. Botev Plovdiv, Slavia Sofia and Levski Sofia were the original teams, and the founding protagonists in a brutal, semi-nefarious yet exciting history that has laced Bulgarian society ever since.

Thirty years later, however, CSKA entered the scene.

The red team (CSKA), the team of the national communist army, quickly rose to greatness and became a Bulgarian football champion in its first year of competition. The dominance once kept and held by the immovable Levski Sofia was disrupted. It could be inferred that those who switched their allegiance to the new starlet CSKA were enticed by the prospects of this meteoric rise to success, and a change in the world of football. Many also consider CSKA the team of the rich, as it was started by the ruling party. In other words, the team was a whirlwind ready to carry new fans off into an exciting future of championships.

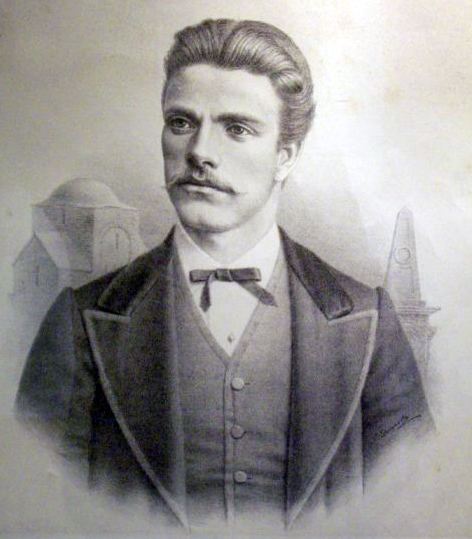

Those that held fast to Levski were holding on to that which had always been. The opposite to the team of the party, this was “the people’s team,” represented by the revered Bulgarian revolutionary Vasil Levski, the “Apostle of Freedom,” executed in 1873 by Ottoman authorities. A team that had always been great and held emblems of the greatness in Bulgaria’s past was being challenged by something new. Today’s Levski fans revel in knowing that their team is in fact the older of the two rivals. One of the distinguishing team cheers is, again, SAMO LEVSKI: Just Levski, nothing else.

I am not leaping to the conclusion that every fan of CSKA is ready to lead Bulgaria into the unknown future, nor am I insinuating that Levski fans are mere nostalgics, determined to hold on to the glories of the past. However, what I discovered in the mythology of the two teams was the parallel that I imagined I might find.

The analogy holds for what I have learned about Bulgaria: pride and reverence for what was once great, versus the prospect of something exciting in the future. The great Bulgarian Empire and the glorious kings and traditions, versus the new intriguing, sometimes disheartening thoughts of a Bulgaria united with the rest of Europe. The original Levski Sofia versus the new CSKA Sofia.

Bulgaria joined the European Union in 2007, and while many found this to be a great leap towards modernization and rebuilding the infrastructure lost to communism, many were aghast at the thought of losing a piece of Bulgaria’s identity to Europe. There’s a push to maintain the rich folk traditions of Bulgarian dance, meals and handicrafts among those who believe that if they comply with the EU they will gradually lose their sense of self as a nation.

On a Thursday night I found myself, in a big crowd of Bulgarians, wrapped up in the heat of a red and blue match. Not having a favored team, I dressed in grey and secretly cheered for both. The gates that lined the field would occasionally be rushed by emotional supporters and when the favored team scored, fans embraced as I’d never seen. I was in the presence of a signature and defining event of Bulgarian culture. The match ended, to everyone’s dissatisfaction, in a tie.

There are two sides of the battle in Bulgaria, two overwhelming directions in which people tend to pull, and these issues explode, from time to time, in an Eternal Derby. The next generation of Bulgarians are obsessed with football, history, and the future of their country. I saw this in my classrooms every day.

Savannah Fortis