In the recession-era early 90s of New York, we newcomers found our jobs in the back of the Village Voice. My first one was at a recycling lot up on 207th Street. Then I answered phones for a PBS profile of Ray Charles, then for a new age TV producer whose phone never rang. The next ad I answered was way more up my alley: working for an Emmy Award-winning gay producer on projects about the labor movement, gay history and gay life in Puerto Rico.

Hurrying past the Fourth Avenue body shops in Brooklyn’s still mostly ungentrified South Park Slope, then waiting on a crumbling brownstone stoop, I lowered my expectations. A gangly white guy in his late 30’s finally answered the door, introduced himself as the filmmaker, and led me upstairs to the third floor, which he shared with a possibly ex-boyfriend and a definitely old cat. On a mantle behind a brown potted palm, I spotted the Emmy Award, coated in dust, and my heart

I aced the interview, but the filmmaker allowed that he was already on the verge of hiring somebody else, fluent in Spanish, a must for the Puerto Rico film. But before I left, he had an idea. During my free time, perhaps I’d like to take charge of another project he was just starting. While he couldn’t pay me, I’d get the title of Associate Producer, which, I would come to realize, meant, “in lieu of payment, here’s an impressive-sounding title.”

When he told me what the project was—a documentary exploring New York’s gay male sexual subculture in the 1970s, before AIDS, using archival material, first-hand recollections, and videotaped “tours” of bars, clubs, bathhouses and cruising spots—I forgot all my disappointment. Sure the title was pretentious and very 90s – “A Geography of Desire.” But I could not imagine anything more perfect. I didn’t quite feel important, but I maybe felt pre-important. I was 23 years old and about to uncover a hidden chapter of my people’s history. I said yes right away and raced home to celebrate with my boyfriend, Brett. As a preschool teacher, he was no stranger to unfair compensation, but he saw and shared my joy.

We had both come of age during the AIDS crisis. The closest I had ever gotten to public sex was smuggling a sociological text called Tearoom Trade: Impersonal Sex in Public Places into the Oberlin library bathroom. And now promiscuity would be my actual job. “Minus the money!” Brett couldn’t resist observing.

For the next few months, I worked three days a week, still clipping newspaper articles for the new age non-producer (until she, too, was broke), but my other two days, and the

In a used porn shop on Hudson Street, I scoured sticky pages of old 1980s Honchos and Drummers for photos that looked like the 70s and weren’t too hardcore, then cut them out and pasted up my first flyer: “REMEMBER SEX BEFORE AIDS?” with the filmmaker’s phone number on little pull-off tabs. Once preschool let out, I dragged Brett around for Happy Hour at gay bars across the city, where we chugged Rolling Rocks and slapped up the flyers.

Using an electric typewriter, I made up entry forms: interviewee, archival material or location. I expected the phone to ring off the hook. It did not. But it did ring, and with a sense of purpose I can only dream of today, I answered every call.

A few men who responded just wanted phone sex. “Punch your balls!” one commanded. But most were legit. They were middle-aged men who had partied their twenties away in the Seventies, survived and/or fought AIDS in their thirties in the Eighties, and now couldn’t quite make sense of still being alive.

Our preliminary phone conversations started out with what bars or clubs or cruising spots they used to frequent, which all of them loved to name and describe in detail: the Cock Ring, the Anvil, the Mount Morris Baths; the trucks, the rambles, the piers. Then I’d ask them about memorable sexual experiences, which were usually focused on quantity (of sex partners, either all at once, or one after another in a single night), or the opposite: a rare moment of transcendent one-on-one connection; evidently exchanging names was the 70s version of falling in love. And then I’d ask them to reflect back on how they felt, from the vantage point of the early 90s. That’s when many of them tended to get mournful or angry or tongue-tied. If they had an emotional pulse—and my standards were pretty low—I interviewed them in person.

Armed with my little notebook and microcassette recorder, I showed up at their apartments in a button-down and cords, my southern accent long

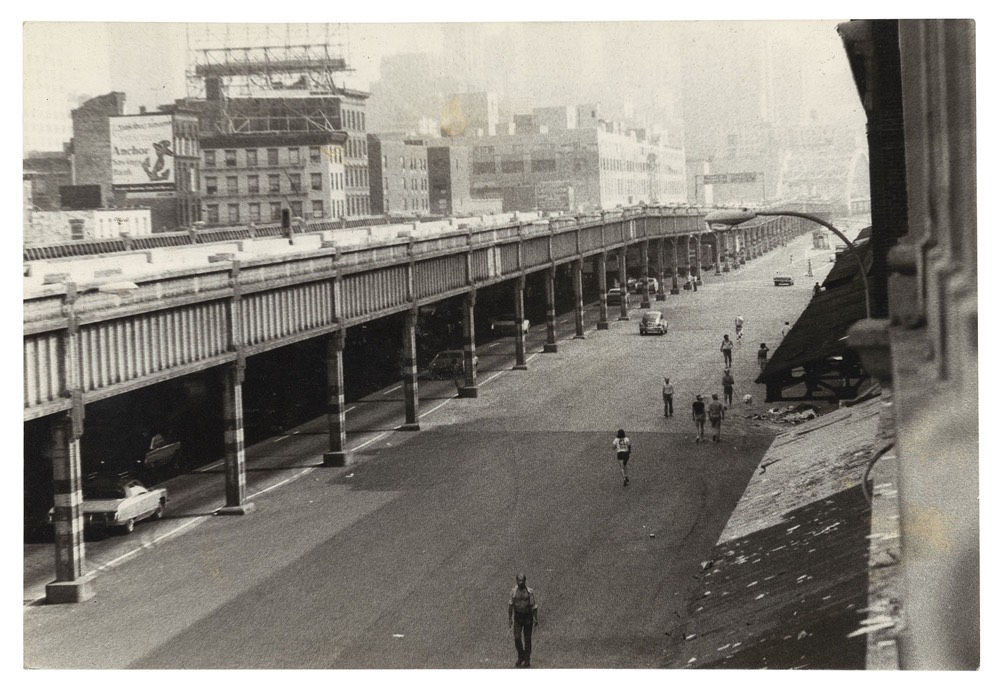

Alvin Baltrop, Courtesy of The Alvin Baltrop Trust, Third Streaming and Galerie Buchholz @All rights reserved.

I gave them space to talk about the sex they’d had before it became so intimately intertwined with death. Arriving in New York, they had fucked with abandon, to get off, to banish shame, and sex had become a huge part of their identities and everyday lives. For some, it became a compulsion, an addiction, a way to avoid intimacy or a long-term career. As they aged, more than one told me they had wondered how long this could keep going on.

AIDS answered that question. Some men were HIV-positive, suffering through early AIDS cocktails, and had given up sex forever. Many had lost everyone they knew and were burying their grief in work. Some were AIDS activists, some had found boyfriends or fuck-buddies, some were still cruising the parks, and some were organizing sex-positive safer-sex parties. If in fact there had been a vibrant sexual subculture that once brought them all together, that had now splintered and vanished.

As incredible as these interviews were, they were only part of the history I was digging up; in the secret gay sexual subculture of 1970s New York, it turns out a lot of guys were carrying cameras. Early on, I stumbled across the collection of a defunct gay porn company that specialized in sex flicks shot in real locations. Amidst all the non-sex “interludes” that normal porn-watchers suffered through impatiently, I found gorgeously gritty 70s New York street scenes, and rare glimpses inside long-gone bars, clubs and bathhouses.

Of all the still photography I came upon, none compared to the work of Al Baltrop, a no-nonsense, cane-carrying heavily bejeweled Afrocentric Vietnam vet, who welcomed me into his cluttered East Village apartment and talked me through his collection: hundreds of jaw-dropping black-and-white images of sexual paradise in the collapsing West Side piers, which he had painstakingly and lovingly documented for years. Unlike Mapplethorpe and other white photographers who shot the piers, Baltrop received scant recognition before his death in 2004.

To get my hands on a giant stack of old bar rags called “Michael’s Thing,” I agreed to two dinner dates with the prospective donor. I can still see his disappointed scowl when I declined his invitation to “get it on.” The magazines were a breakthrough trove of visuals and information: ads for a club called The Toilet, hand-drawn by Warhol; street addresses and descriptions of the tiniest gay establishments.

Armed with all that data, I took Brett out on history-lesson/location-scouting “dates.” Sometimes, I brought along tapes of my pre-interviews that included stories of the spots we were visiting, and Brett and I would stand there in the street, ears pressed to the recorder, listening. Everywhere we went, I took Polaroids – from the Adonis, a grand old shuttered Times Square sex theater, to the Paradise Garage,

I eventually had to admit that my research had successfully snowballed into too much work for me to keep doing alone. With money from two new jobs for the hospital workers’ union, the filmmaker was able to hire me full-time, for the princely sum of $350 per week. And now, instead of all that hands-on/out-in-the-city research, I found myself hiring and managing a constant stream of unpaid or barely-paid interns.

I had never managed anyone before and had no idea what I was doing. Since the filmmaker was often working elsewhere, and the interns were no more than two years younger than me, I did what felt natural and bonded with them as peers. A willowy, charmingly beleaguered bisexual woman took charge of making a full-city location sex map and then, with a pirated copy of FileMaker Pro 2.0, built interlocking databases for all of my handwritten research. She did a stunning job at both (these days, she works in Digital Repositories and Scholarly Communication at an Ivy League university). A raggedy crew of young men set out with my cassette recorder to gather more interviews, then came back to transcribe them on the failing Apple Lisa. A lesbian/proto-genderqueer (who now runs a global LGBTQ human rights organization) spent weeks in the little side-office/editing studio, cutting together clips from our on-the-street interviews and hours of archival footage into a VHS trailer for the film: men dancing in bathhouses, cruising under the elevated West Side Highway, kneeling at a wall of well-stuffed glory-holes; a strange period clip of an African-American leather top bellowing to the camera. “If you put your arm in somebody’s ass or somebody’s rectum,” he said, “You’ve got to know what you’re doing!” All to the haunting but period-inaccurate chorus of Bronski Beat’s “Smalltown Boy.”

I remember life with the interns the way our interviewees remembered life with limitless dick: with a surge of dopamine and a repressed sob. When the filmmaker’s eight-year-old son bounded in for his once-a-month Daddy Weekend, we all rushed to hide the porn. A young gay intern with a beard and braids, who would go on to run an acclaimed experimental film festival, offered a sly critique of 1970s hyper-masculinity that was way ahead of its time. One day the filmmaker canceled work for everyone so we could watch together in horror as Orrin Hatch and Joe Biden destroyed Anita Hill. And once, waiting for the subway after work, the genderqueer editor confessed to me that her true calling was performance art: “I need to put my body on the line!”

Over lunch one day, I cracked the crew up with my dumb idea for a slogan for the fast-hardening chocolate ice-cream syrup we had found in the

In mid-1993, frustrated by a spate of cold rejections from funders big and small, the filmmaker at last lurched into on-the-fly production mode, hoping that a half-shot documentary would come across as more of a bankable investment. We were all overjoyed: finally, actual filming!

The hardest shoots to pull off were the “tours.” Before our interviewees could guide us around their old haunts, I had to secure access for filming from the spaces’ current owners. In the case of a wholesale fabric mall on West 28th Street, former home of the Ever(h)

The sit-down interview I most remember was singer and AIDS activist Michael Callen, who rose to the occasion in spite of his decimated immune system. He regaled us with the hilarious tale of being one of a crowd of top-less bottoms on the roof of the St. Marks Baths. He chronicled the controversy that ensued in 1983 when he and fellow activist Richard Berkowitz dared to suggest that promiscuity was causing the spread of AIDS. He talked about being killed by the thing that had liberated him. He died in December 1993, less than a year after we interviewed him.

Armed now with hours of original footage, the filmmaker opted not to beat his head against the wall again with traditional funders, and instead, went straight to individual donors. A gay marketing expert sold us a mailing list of high-powered homosexuals, and between that and the filmmaker’s Rolodex, we were ready. We agonized for weeks over a beautiful bound proposal, worked the phones like crazy, organized donor dinner-parties and screened highlights of the new footage wherever we could.

As devastated as the filmmaker was, he did his best to shield me from the full weight of his defeat. We would soldier on, he insisted gamely. And we did, for a while, until his paid work dried up and he had to leave New York. One intern’s final job was helping me to box up all of our work—the tapes, the proposals, the bar rags, the lovingly detailed sex-map—and drive it out to the filmmaker’s mom’s house by JFK. Some of it stayed there, some of it went with the filmmaker, and for a time some of it sat in a filing cabinet in my apartment, waiting for resurrection. Eventually, both the filmmaker and I moved on to well-paying long-term jobs, and “Desire” slid quietly into its grave. When Brett and I were evicted from our Ludlow St. apartment so the building could be turned into luxury condos, the filmmaker moved most of the material to a colleague’s storage space at Hunter College, where it remains to this day.

In the mid-late 90s, when my friend, the artist A.K. Summers, moved to New York, the “Desire” work found a brief new purpose: as research material, visual reference and inspiration for a single-issue comic-book collaboration called “Meat Park.” A “Westworld” takeoff, our comic told the story of an AIDS-era theme park simulacrum of the pre-AIDS New York gay sex world, populated by fisting robot tops and cum-hungry robot bottoms, who all of a sudden malfunction and revolt. Nobody wanted that, either. Then in 2005, over a decade after we began “Desire,” another documentary came out on pretty much the exact same topic. I couldn’t bear to watch it.

“Desire” was not my first unfinished project, nor my last. But it remains the most painful. For years, we’d worked to unearth an incredible history buried by shame and death and grief. We promised these men that they would be heard. And then we packed up their history and buried it all over again. Finally, Al Baltrop is getting the recognition he deserves with an upcoming show at the Bronx Museum of the Arts. But the other men, left boxed-up, still haunt me.

Working on the film was how I fell in love with New York, by seeing the layers of its subcultures in physical space, by connecting my own layer with the ones before. In the early 90s, the New York of the 70s

Last spring, just around the corner from our apartment in lower-west Manhattan, Brett and I watched a wrecking ball lay waste to the Paradise Garage. To cheer me up, he reached his arms up in the air as if to try to catch the wrecking ball, and cried out in a gurgly baby-voice: “Ballie!”

Later, I shared the news of the loss over drinks with some white middle-aged homosexuals like myself. I also groused that the long-gone piers, once a magnificently filthy urban eyesore, were being “memorialized” with a politely sexless sculpture across from the new Whitney Museum. Instead of sympathy, I got eye-rolls. Everyone invented their own New York out of the remnants of someone else’s New York, and that’s just how cities work. You’re not sad for a lost place, Tal, you’re sad for a lost version of yourself.

I stewed in silence. Walking home, I remembered that lost version of myself; someone who, before he could even fathom his own erased New York, was already living in and mourning someone else’s.

Tal McThenia