I was twenty-four the first time it came to me that I was going bald. I had been soaking in the bath, trying to get some warmth in a cold unheated house. After I had dried my hair with the towel, I caught sight of myself in the mirror over the basin. With a shock, I realised that I could see the outline of my scalp under the roughed up hair. It was jarring to confront, suddenly, that underneath that formerly thick and lustrous crop, there was a skull. I was reminded of my grandmother. Mortality stared at me from the bathroom wall.

Having somehow survived the next forty years or so, I found myself one afternoon on my back in an emergency room where a burly male nurse was energetically jamming a thick tube up my penis into my bladder, and, through the disturbance felt in my innermost being, I began to understand that baldness is relatively minor in the hierarchy of afflictions men may come to endure.

Oddly, it turns out, there may be a connection between these two traumas.

My symptoms had begun a number of years before the emergency room visit when, in the men’s room at the office, I noticed that it was taking longer than usual to—as they say—water the horse. While my fellows poured forth their effortless cataracts, I stood waiting expectantly for my own flow, which was by comparison, when it came at last, a feeble rivulet. Two or three men might visit the other of the pair of urinals and chat, or not, while I finished my business. It began to get embarrassing, to the extent that I would go instead into a stall and click the lock behind me.

Not being a big fan of doctor visits, I took to the web and soon concluded that I was suffering from an enlarged prostate. [trigger warning: not for the squeamish] This normally quite small gland sits at the base of your bladder—assuming you’re a man, obviously—and the urethra, the narrow channel that carries the contents from your bladder to the outside world, passes right through the middle of it like a wormhole through an apple. When you’re a child, your prostate is only about the size of a pea. At puberty, it starts to grow, stopping some time in your twenties, at which point it’s about the size of a walnut (maybe 25 cubic centimeters). When you get to 40 or so, it begins to grow again, and it can get big enough that there’s no longer much room for the urethra running through its middle. Sometimes it just grows right into the bladder and guards the exit. Hence these difficulties in the men’s room.

Of the treatments listed on the various websites, the easiest was called “watchful waiting”, and I watchfully waited for a number of years. Nothing very much changed. For a while I was having to get up in the middle of the night, but I dropped the habit of drinking coffee just before bed and that did the trick; most of the time, I could sleep through. The odd thing was, even though I could hold a full bladder without any trouble, when once the thought came into my mind that I was going to go, I had to get there very quickly. Also, every time I turned on the kitchen taps to do the dishes, the urge would swiftly come upon me and I would have to hurriedly dry my hands and run to the bathroom. It was a strange psychological sort of quirk, though, that if I knew there was no bathroom nearby I would feel no great urgency, but as soon as the means and the opportunity arose simultaneously, the motive became quite compelling. So, it was manageable. There were no disasters other than the occasional drop of pee on the tiles marking my failure to arrive at the bowl in time. Watch. Wait.

Then one day I noticed something weird. My abdomen had grown a sort of unprecedented rigidity. Rock hard. I thought it might just be that the low-carb diet on which I had recently embarked was causing my body fat to disappear, uncovering the muscle beneath. But in my heart I knew this wasn’t the answer – my muscle was never that hard. I thought it might be some sort of rigor protecting a hernia. I had a slightly uneasy feeling it might be the dreaded “c”. But it didn’t hurt and there weren’t any other symptoms. I decided some more watchful waiting was in order and a few weeks later my wife and I headed off for a six-week vacation abroad. The rock stayed put, maybe spread a little. Also, it moved slightly to one side, where there was now a modest but perceptible bulge. When we got home I finally went to Urgent Care: with my HMO you have to wait quite a while for an appointment with your doc; Urgent Care is the easiest option. I little expected the saga that was awaiting me.

The Urgent Care doctor was a little baffled. She agreed it might be a hernia, but these weren’t classic symptoms so she sent me down for a scan. I drank a rather disgusting barium smoothie, waited a while, changed into one of those flimsy, undignified garments they give you, and was rolled on my back into the CT machine. The scan took no time at all and made me feel strangely warm. The results came back an hour or two later.

“That thing is your bladder”, the doc said. “It’s huge. There’s a lot of liquid in there and we need to get it out with a catheter.” She explained that the sudden release might disturb my electrolyte balance. “So we’re going to send you over to Emergency where they’re better equipped to keep an eye on you.”

She explained about the catheter. It sounded a little daunting, but harmless enough. Put in a tube, drain out the pee, check the electrolytes, and I could go off about my business, I thought. My second trauma, following the shock of discovering my incipient balding, was about to begin.

The emergency room nurse, whose name was I think George, took 1,700 ccs of pee out. (Just to give an idea, that’s almost five Talls at Starbucks. I weighed about 135 lbs at the time. No wonder there was a slight bulge.) When I asked him to remove the tube, he said he would first have to get one of the urologists. Unfortunately, there weren’t any around at the time.

“You mean”, I asked him, “I have to go overnight with this thing?”

“Well, it’s Friday”, he said. “So probably the weekend.”

“The whole weekend?” I asked. “But what about sex?”

It had been a few days.

He shrugged. He said to go home and a urologist would call me “next week.” There was something a little diffident, almost shifty, in his manner. And no wonder, as it turned out.

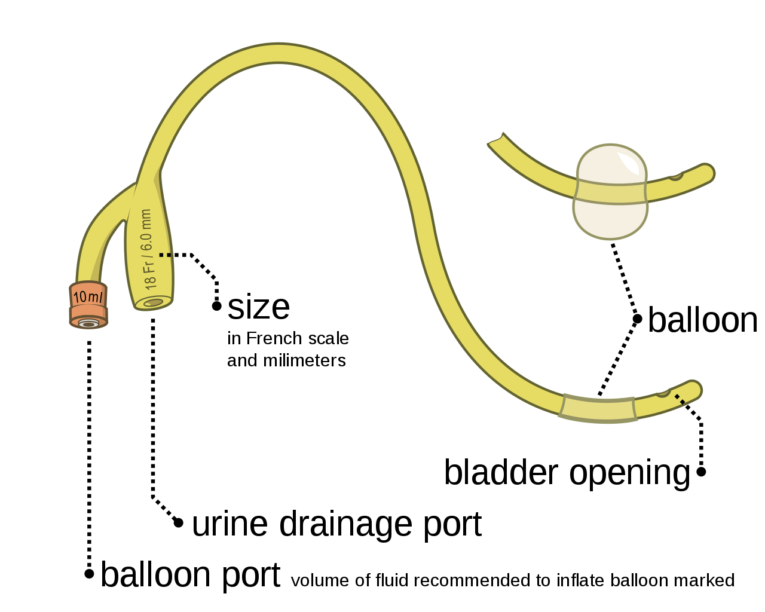

The Foley catheter is a double tube. The main one is the drainage tube which drains the liquid from your bladder. The narrower one ends in a small inflatable balloon which protrudes into the bladder where, pumped full of water and plugged, it makes a bulge which prevents the whole thing from falling out.

Olek Remesz [CC BY-SA 3.0] via Wikimedia Commons

Olek Remesz [CC BY-SA 3.0] via Wikimedia CommonsAt the other, penile end, the drain tube goes through to a little swivel gizmo taped to your thigh. The weiner is held to one side, therefore, and if you wear tighty whities like I do it has to go under the seam where the leg-hole is. This tube connects to another one which goes down your leg to a plastic reservoir which you wear strapped discreetly to your ankle. It has a little plastic spigot on it. The pee drains more or less continuously into this bag, and every so often you empty it. (This turned out to be quite handy: you can just bend down as if tying your shoelace and pee on the grass, like a dog, only with a little more subtlety. One of the very few benefits.) When you walk or move around, the tube tends to jog your schlong around a bit, and it can get a little sore as a result. You can steady it a bit by putting your hand in your pocket and holding. It helps, also, to take shorter steps, which is partly why wearing it makes you feel like an old man. At bedtime you swap the ankle bag for a more capacious “night bag”, which you hang on the bedframe below the level of the mattress. You have to sleep carefully in case it comes unplugged, flooding the mattress. Which means you tend to sleep uneasily.

I don’t know what diameter Foley they used (it commonly ranges up to about 9 millimeters, so picture the slug of a handgun), but whatever it was it wrought havoc with my insides. The car ride home was a bit of a trial. There was a lot of blood, and it seemed to clog so that I felt that I needed to pee but couldn’t. There were some quite painful uncontrolled spasms as my bladder tried to squeeze it out. I had to stop at a Starbucks to empty a bag of stringy blood clots. I hoped fervently that they could take the thing out on Monday and I could start peeing (relatively) normally again.

Nobody had told me before I wandered unsuspecting into the ER that I would come out with a tube in my junk and a bag strapped to my ankle. As far as I could tell there hadn’t been any imminent danger: after all, I had had this rock in my abdomen for a couple of months at this point, without any perceptible mishap. You would have thought they might have given me some advance notice of what I was letting myself in for before I agreed to the procedure. You would have thought they might have tried a smaller diameter catheter first, one less inclined to tear up my urinary tract. Doctors can be a devious lot, one learned, and surprisingly nonchalant about one’s comfort. Living with a Foley was no fucking fun. It’s not that it’s comparable to, say, the chronic pain associated with a lot of the ills that old flesh is heir to. It’s not like having a stroke or being in a wheelchair, or even severe arthritis. But it is debilitating. I felt about twenty years older. I couldn’t wait to get it out.

Evidently, the urologist wasn’t in as much of a hurry as I was, because the promised call didn’t come through.

In the meantime, my wife and I were doing some research.

There are various options for treating the inaptly named Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia, aka Hypertrophy (BPH). In mild cases you can take one or a combo of three kinds of drugs.

One type is an “alpha blocker”, essentially a muscle relaxant which, by working on nerves controlling the muscle tissue of the prostate, helps to ease the pressure on the urethra. The list of possible side effects is quite long and includes dizziness, drowsiness, fatigue, and, curiously, both erectile dysfunction (ED) and priapism (prolonged and painful erections), as well as the destruction of, or other interference with, your ability to ejaculate.

The second kind (a”5-alpha reductase inhibitor”) slows down production of dihydrotesterone, a hormone which promotes enlargement of the prostate, thereby tending to shrink it. This explains why men who have been castrated when still young do not develop BPH. They also, incidentally, do not go bald. Hence the distant connection between my young and old selves. Another effect of DHT is to make you feel horny, so this type of drug is likely to undermine your libido, if you have any left at this point, thereby pretty much putting an end to your sex life.

The third drug, oddly, is tadalafil, more commonly known as Cialis and designed to have the reverse effect, or at least give the appearance of having done so in the form of a responsively upstanding member. Along with Viagra and Levitra, phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors are muscle relaxants which specifically target erectile tissue but also happen to work on muscle in the nearby prostate and bladder. Cialis, which has a much longer half life than its rivals (and so is known among ED afficionadi as “the weekend pill”), is the only one specifically approved by the FDA for BPH. The most common side effect is headache.

So which one would you rather take? The one that destroys your libido, the one that interferes with normal ejaculation or the one that treats your condition while also, coincidentally, strengthening your erection?

While the choice looked pretty clear to me, unfortunately these drugs can only help if your prostate isn’t too large. A “normal” prostate in a 25-ish man is reckoned to be between 15 and 30 ccs. Fifty or 60ccs is considered quite enlarged. Mine, according to the CT scan, was around 175 ccs, about the size of a plum or a modest peach. There’s more to it than just size, because men with small prostates can still have the flow problems and men with quite large ones can be symptom-free. The shape also seems to count: a protrusion of your prostate into the bladder can flop around and block the exit, like a valve. Either way, there was little chance any of the drugs would help.

By Thursday, six days after the installation of the Foley plumbing, still no urologist had called and I was getting quite weary of it, so I called my HMO again. They took a message again. Eventually, they gave me an appointment for a phone consult, but I had to wait until the following week. By the time I actually talked to a urologist, I had been wearing the Foley for 12 morale-sapping days. He cheerfully recommended getting something called a TURP together with a suprapubic catheter. A very routine procedure, he assured me, nothing to it. In my case, he thought, what with the supersize prostate and something called a “median lobe”, there wasn’t really any choice. He urged me to name the day.

TURP stands for Transurethral Resection of the Prostate. “Resection” is just one of those euphemisms doctors are so fond of; it means “removal”, in whole or part. The “Transurethral” just means they do it by going up your urethra, the same way as the Foley, and doing the excavation from within, like a termite in a joist. It’s more or less the drilling of a tunnel to reopen the path blocked by the enlarged prostate. Among people who have had it, it’s sometimes called “the roto-rooter.”

TURP goes back quite a long way. In 1575, a famous French surgeon, Ambroise Paré, invented the first device known to have been used for transurethral surgery. Men had been using catheters since time immemorial, and Paré’s device was an extension of that idea. It was basically a catheter with a stiff wire going through it. There was a hemispere on the end of the wire which you could push through prostate tissue obstructing the way to the bladder. Then when you drew it back against the sharp edge of the tube, the tissue would be lopped off.

British Association of Urological Surgeons, Virtual Museum

British Association of Urological Surgeons, Virtual MuseumThis was the state of the art for about 250 years until in the 1830s and 1840s instruments came into use which used cutting blades, similarly introduced through an outer tube or sheath. In 1873 an Italian surgeon, Enrico Bottini, demonstrated “galvanocautery”, using instead of a blade a red hot platinum plate powered by a battery. According to Willy Meyer, MD, who gave a riveting talk (pdf) on Bottini’s operation in 1898 in Albany, New York, an assistant listening close above the patient’s abdomen could hear (“auscultate,” in the polysyllabic periphrasis so beloved of doctors) the sizzling of the tissue as it was burned. Once the dead material or “eschar” fell away—anything from five days to a month later—voilà! Or rather, in the case of Bottini, ecco!

These procedures were all done blind, so to speak. Presumably you could tell when you had got to the bladder by the outflow of urine, but otherwise it must have been largely a matter of “feel.” In 1877, the cystoscope—an optical instrument for looking inside the urethra and bladder—was invented, and shortly thereafter, Edison’s incandescent bulb to shed light in the dark interior. Being able to see what you were doing, at least in a limited way, must have helped quite a bit. Meyer claimed that Bottini had had good results with this equipment:

Bottini has had but two deaths in a series of more than eighty cases—certainly a minimal death rate for an operation which is almost exclusively performed on old and decrepit patients; and these two deaths occurred before the cooling device had been added to the cauterizator.

The “cooling device” added in 1882 was essentially a pipe system which circulated cold water, cooling the blunt end of the equipment and thus “[saving] the urethra, prostate, and bladder from accidental burns.“

Meyer himself had lost one patient out of the two he had performed the Bottini on by the time he gave this paper, though there were mitigating circumstances in the case of the dead man and the one success seemed salutary: He enjoyed life and regretted the loss of his testicles (which had been removed previously, a then common procedure supposed to shrink the prostate). Meyer’s plugs for the equipment, and the fact that his pamphlet had on the back an advertisement from the manufacturer, may have had something to do with his positive view of the Bottini method.

Medical Record, 1898

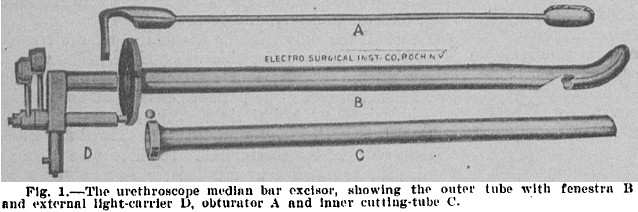

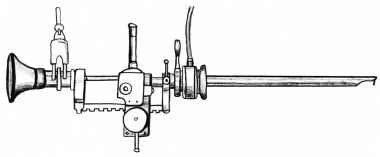

Medical Record, 1898Despite that these operations were essentially TURPs, credit for the first TURP is usually given to a Baltimore doctor by the name of Hugh Hampton Young. Discouraged by the death of a patient whom he had operated on by cutting through the abdominal wall (i.e. rather than through the urethra), in 1909 he designed (pdf) the first of what became known as a resectoscope (which he called a punch or median bar excisor).

Journal of the American Medical Association, 1913

Journal of the American Medical Association, 1913There was a notch or “fenestra” in the outer tube designed to allow pieces of tissue to protrude into it. An inner tube with a sharp end could then be slid along to slice through the tissue. You could turn it to cut in more than one direction, though the “six o’ clock” cut was always the largest. There was an external light so that you could see roughly what you were doing, or about to do.

Note that this equipment is, except for a slight turn at the end, straight. The urethra, on the other hand, goes through the best part of a right-angle turn before it enters the bladder. Young used cocaine as a local anaesthetic to cope with whatever discomfort this geometrical incompatibility might have caused.

By the 1930s, the resectoscope looked something like what might have been used, (aptly enough, it turns out), in the St Valentine’s Day massacre, only smaller:

1932 Stern-McCarthy resectoscope with rack-and-pinion working element

1932 Stern-McCarthy resectoscope with rack-and-pinion working elementThe TURP became the mainstream procedure for Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (LUTS) caused by BPH throughout the twentieth century and even up to this day. In the peak years of the 1980s, it is reckoned about 350,000 TURPs were performed in the US annually (the most frequent operation within Medicare, the nearest rival being cataract surgery). With the development of the aforementioned drugs, lower physician reimbursement for the operation, the rise of alternative surgeries, and perhaps increasing negative scuttlebutt facilitated by the internet, it has probably declined to something over 100,000 old codgers per year now. The equipment has been refined over the years. Bottini would no doubt be pleased to know that the cutting edge of the modern resectoscope is a wire loop which works using electrically generated heat (“fulguration”). The heat, as well as cutting, can be used to seal leaking blood vessels. Galvanocautery still rules.

McMillen, Arch S., "Trans urethral resection of prostatic obstruction" (1934). MD Theses. Paper 623.

McMillen, Arch S., "Trans urethral resection of prostatic obstruction" (1934). MD Theses. Paper 623.The trouble with TURP is the potential side effects. It is a tricky operation with a steep learning curve. Even though visibility has improved a lot since Paré’s time, the surgeon still can lose orientation and has to concentrate to know exactly what he or she is cutting at any one time. Cutting the wrong part can be very damaging or even (albeit rarely) fatal. There is time pressure, because if the operation goes on for much more than 90 minutes the constant flushing with sterile solution can dilute the body’s sodium – “dilutional hyponatremia” is mainly what can kill you. (The introduction of an electrically bipolar resectoscope allowing the use of conductive saline is reducing this risk). At the same time, there is pressure to take out as much tissue as possible: “It is not how much is taken out that causes the postoperative problems, it is how much is left in,” say the urological veterans, apparently. Willy Meyer’s performances of the Bottini procedure were over in a matter of five or six minutes, but it is reckoned now that a large prostate can be excavated in under 90 minutes only by a skilled and experienced surgeon. So if your prostate is over, say, 100cc, you might not want to be the patient on whom a young urologist gets his early practice.

The prostate is central to a man’s sexual function, so it may not be surprising that when most of it is “resected” you may lose effectiveness in that area. Some of the prostate is dedicated to producing fluid which carries sperm cells, made in the testicles, to their destination during orgasm. Some of it is muscle which expels this fluid into the urethra. Various other maneuvers are necessary for satisfactory propulsion. The urethra narrows, focusing the stream; and the sphincter at the inside end of the prostate tightens to close off the bladder. If the opening to the bladder isn’t sealed off, you get what they call “retrograde ejaculation”: the fluid takes the path of least resistance back into the bladder, and you have a so-called “dry” orgasm.

Apparently, messing around near the sphincter at the bladder neck, with its accompanying nerves, almost inevitably damages its responsiveness: as many as 90% of men who undergo TURP have retrograde ejaculation. Urologists, it seems, tend to downplay this to prospective patients. You’ll still have an orgasm! Look on the bright side: you probably don’t need contraception any more!

But here’s a sample of what you read on the bulletin boards where men who have had the operation share their experiences:

I had this butchery 3 years ago and live in a state of depression ever since. I was not told of other treatments and had a ridiculous (and misplaced) faith in my surgeon who at no time suggested other forms of non emasculatory procedures.

Not a day goes by that I [don’t] regret the decision to have a TURP.

Worse than decreased sexual pleasure is that dry orgasm does not relieve sexual tension barely at all. We become more tense and depressed. thus our health in general goes downhill.

But unlike many wives that understand, mine divorced me as I had little desire for sex and it was painful and unsatisfying when I did, especially with the MUSE [a treatment for erectile dysfunction].

Now, I don’t dare try to even date as I know I won’t be able to satisfy them at all.

My ex wife now calls me gay because I don’t get aroused with her. [No explanation of why this issue still comes up since the divorce].

It’s so depressing, I have constant thoughts of suicide because of it.

I am now sterile, have low libido/said dissatisfaction, and incontinent after every single urination. I was never incontinent before.

I have RE after the TURP and I hate every moment of it. The climax is absolutely pathetic . I cant think how most men dont have any problem with it and there is nothing worse than sex without an ending.

Among other possible side effects of TURP are incontinence – particularly “urge incontinence” which tends to come upon you with no warning, with potentially embarrassing results. Men complain of having to be near a toilet literally all the time. There is also, potentially, the inability to get a timely erection (ED).

Although not every narrator on the forums suffered sexual death, and there were those who took a more stoical, count-your-blessings kind of approach, I tend towards the astoical camp and thought it best to look for other avenues. Meanwhile, any ideas that I might have had about giving relief to my sexual urges were obliterated by the continuing presence of a thick plastic tube protruding from the organ through whose agency such relief might have been expected to come.

There are a number of surgical alternatives to TURP, all with the one necessary feature in common: destruction of prostate tissue. There are several variations on the theme of a laser, one of which literally vaporizes the cells. You can get the tissue microwaved. There is a procedure involving a needle and radio waves. You can broil with heat generated by ultrasound. The latest, even approved by the NHS in Britain, is poaching with blasts of steam. Although some of the laser methods seem encouraging, there is no escaping the feeling that when you destroy cells important to sexual functioning, sexual dysfunction is a likely result, and most if not all of these involve the risk of retroejaculation, ED, incontinence or any combination of these.

Then there is Urolift. Very little tissue is destroyed with this technique, which is more like a construction job. The urethra is widened by being pulled apart rather than excavated. Staples are put in the inside of the, so to speak, tunnel walls. They are attached to little teflon cables, which are poked through to the outside surface of the prostate. The cables, anchored on the outside by more staples, are pulled tight enough to open the tunnel. This seems to have worked with some people, though the procedure hasn’t been tested for long-term durability, and it is less effective than, for example, TURP for treating urine flow and retention. It was critiqued in an English journal in 2016, which noted that no patient in the studies had reported de novo symptoms of sexual dysfunction. Hooray! There were, though, some caveats.

Firstly, the published outcomes have been achieved by investigators within a clinical trial setting who are highly motivated, with an invested interest to actively develop the technique. Moreover, the majority of studies have been funded by the manufacturer.

Secondly, this technique only seems to work in quite specific cases: relatively small prostates (none larger than 50ccs in the tests cited), where there is no obstructing median lobe and no history of urine retention. I was disqualified on at least two and probably all three counts. The future took a dimmer tone.

Then, however, my wonderfully diligent, determined and caring wife found PAE. Prostatic Artery Embolization (pdf) is a technique for blocking off the arteries which supply blood to the prostate, thereby killing off a portion of its cells and causing it to shrink, slowly and without direct or mechanical violence to the tissue.

Medics had had the same idea a long time before, in the nineteenth century.The aforementioned Doctor Willy Meyer thought it very promising. The modern technique, whereby the blockage of the arteries is achieved by plugging it from within using a very fine catheter inserted, usually, through the femoral artery (sometimes the radial artery, at the wrist), was obviously not available in those days. Meyer did it by tying or “ligating” the arteries with catgut or silk thread. He had performed the operation twice by 1894 when, on April Fool’s Day, he gave his paper to the New York Surgical Society. It was a difficult procedure which resulted in the first patient losing part of a foot to gangrene (but partially regaining his ability to pee) and the second dying in a coma eight days after the operation (though before dying he showed marked improvement in his LUTS, so Meyer was able to claim “Certainly the functional result of the operation had been all that could have been desired“). The pioneer in the technique, a Dr. Bier of Kiel in Germany, lost two out of three patients on whom he tried it. For some reason, ligation of the iliac arteries as a cure for BPH did not catch on.

More recently, in the 1970s PAE was used as a “salvage therapy” for men whose blood vessels had been compromised during biopsy or surgery of the prostate (“iatrogenically”, as the circumlocutory medicos like to say); and the same basic idea has for some time been used successfully to shrink growths in the uterus. In 2000, a doctor decided to try it on a man whose heart was too weak to withstand conventional BPH surgery, with satisfactory results. It seemed to fall into disuse as a BPH treatment until, in 2010, a doctor in Brazil published his report on strikingly successful operations he had performed with two patients in 2008: the prostates shrank quite dramatically, urinary symptoms were relieved and there were no side effects. (Previous experiments with pigs and dogs had already shown that PAE could shrink the prostate without affecting sexual or erectile function). With increasing use and more data, PAE gained in popularity and the FDA approved it as a “standard of care” in June 2017.

Perhaps not surprisingly, since it’s a relatively new procedure, my HMO didn’t offer PAE, at least as far as we could discover. That most likely meant I would have to pay for it out of pocket. I had no idea how much it would cost. The first step, though, would be to find someone who could do it, preferably someone not too far away. The first place my wife found was in Australia. The second was in Virginia. The doctor in Virginia was very pleasant, informative and helpful. But he was across the country, in Virginia, and we would need to go there not only for the operation but also for at least one followup. And then we found Dr Justin McWilliams right in Los Angeles and managed to get him on the phone.

Dr McWilliams, it turned out, had studied under the Brazilian doctor, Francisco Carnevale, whose 2010 paper had done so much to propel PAE to the forefront of BPH treatment. He was everything you could wish for in a doctor: authoritative, knowledgeable and confident without that brusque, patronizing or dogmatic air so common in members of his profession; attentive and respectful; practical in discussing the economic aspects. He gave me a quote, which included a visit to a urologist colleague to ensure that I was a suitable candidate, and a follow up. As for Medicare paying for it, that was “a grey area.” It was a fair amount of money. Being on the whole quite fond of a dollar, I had misgivings. But my persuasive wife was quite emphatic that we should go ahead, and we scheduled the operation.

In the urologist’s office, they took out the Foley. It had been in there about three weeks by this time, and it was quite a relief to feel so free of the encumbrance. It didn’t last, however, because he put me in a sort of dentist chair and slid a cystocope up my urethra where the Foley had been. There was a screen which showed the view as he moved it about. One thinks of urine as being quite a clear liquid, and I was surprised at the debris floating around in my bladder. It was rather like The Upside Down in Stranger Things, only lighter and more pink. My bladder wall, the urologist told me, had thickened somewhat, which wasn’t uncommon in patients who had been straining to pee for a long period: The bladder wall is partly muscular, and my bladder had been doing weights at the gym every day for a good few years. This was not a good thing. I asked him if he thought the PAE would work. He said nothing but the tilt of his head and the skeptical eyebrows were eloquent enough. I put this down partly to the natural resentment of urologists whose livelihoods as TURP practitioners might be threatened by the new procedure, which is performed by interventional radiologists. But there was no medical objection to my trying it. Unfortunately, after the examination was over he insisted on putting in a new Foley. It seemed I would never get rid of it.

The PAE itself followed a week later. It was really nothing. Dr McWilliams made a pinprick incision in my lower abdomen just above my right leg and inserted a thin catheter. There was a bulky apparatus a couple of feet above the operating table which was evidently a scanner of some kind enabling him to see what he was doing. Every once in a while it was trundled in a semicircular arc over me, presumably to get the side views. I don’t know how they steer those long, seemingly flimsy catheters, but somehow he managed to navigate through the arterial system to the appropriate spots – one on each side — and deposit the tiny plastic spheres which block the blood from getting to the prostate. (It can be nasty if the blockage is put in the wrong place by mistake, cutting off blood to the bladder, anus or penis; so you want to have confidence in your radiologist).The whole thing probably took an hour, and after another hour or so in recovery I was out of there. I’d been told I might have some pain over the next couple of days but I felt none at all, didn’t even need a non-aspirin aspirin. The incision in my femoral artery sprang a small leak a few days afterwards, but I soon staunched it. Over the next six months, my prostate shrank from 175cc to 120cc.

I wish I could say that I had a miraculous cure and could suddenly pee like a racehorse, but the real world doesn’t always work that way. The good news is that my HMO urologist at last conceded defeat about a fortnight after the PAE and removed the Foley. It had been a long six weeks. Just the thought of not having to shuffle around with that tubing system made me feel about 20 years younger. The less good news followed very shortly afterwards: the nurse filled my bladder with water until I felt quite full and when I tried to pee, even though I felt like I needed to, I just couldn’t. My bladder, the doctor explained, had lost its ability to squeeze.

“It’s like an old pair of underpants”, he said. “The band stretched too much for too long and now it has no elasticity.”

“But it’ll come back?”

He gave me what I had come to view as the Urologist Look, the tilted head and skeptical eyebrows, and asked me if I had ever known old underpants recover their spring.

“Yes, but underpants are inanimate. Surely living things regenerate all the time?”

Another Urologist Look. I don’t know whether they teach them this during the residency, or whether it just evolves naturally from always having to break bad news to their patients. It seems to go back a long way, as the prostate pioneer Sir Everard Home, Bart., VPRS, Serjeant Surgeon to King George III, observed in 1818:

Experience then too often produces [in older doctors] timidity, irresolution, and distrust in the efficacy of medicine, which renders the mind incapable of continuing to prosecute medical science ; and the practitioner falls into a state of apathy, in which he is satisfied with doing his best endeavours to palliate the symptoms respecting which he is consulted.

And so now I am what Willy Meyer and Hugo Hampton Young used to call a “catheter slave.” Three times a day I go for a walk to limber up – this has always helped the flow, even in the watching and waiting days. Then I stand in front of a measuring cup waiting for the delivery. I void what I can, usually in three or four bursts with a few minutes in between. Then with my twice-washed hands, I lubricate and push a sterile, single-use catheter ten inches up my urethra into my bladder to drain the rest with gravity. The catheter is much more svelte than the Foley. You would think that shoving something like that up your johnson would be painful and uncomfortable, but really it is less traumatic than brushing your teeth. Mainly the whole thing is just tedious and time consuming. I could just go ahead and drain it all in a couple of minutes, but I’m still hoping, almost two years later, that I’ll learn to pee naturally again with practice; there’s been a slow but steady improvement, and success is not unknown. Meanwhile, I’m getting quite good at the crossword.

What seems strange to me is that, considering how much they already knew 100 years ago, we still know so little. We don’t know why one man gets BPH and an other doesn’t, what causes BPH (except that it’s probably not, as Sir Everard thought, too much riding about on horses or “induced by the appetite it produced, [making] free with the pleasures of the table“). We don’t really seem to understand how prostate size relates to actual symptoms, or why symptoms vary between one patient and another. And so far, other than killing fewer patients, we haven’t really made as much progress in treating the symptoms as has been made in many other branches of medicine. Millions of old men still lead highly circumscribed lives because of the side effects of the surgeries and drugs.

One regrettable problem seems to be the overwhelming preference of urologists for TURP. The rule seems to be, “If in doubt, recommend TURP” (something which is borne out by one fairly recent study, showing many doctors recommending it even when the chances of success are quite small). TURP in a likely majority of cases causes damage which cannot be reversed, having side effects which many patients apparently find more irksome than the original symptoms. PAE seems to achieve results which are almost as good TURP in treating LUTS, but with almost no side effects. Yet, in its page on BPH, the foundation of the American Urological Association doesn’t even mention PAE. It is hard not to suspect that they don’t want to divert lucrative patients to radiologists.

I can still hear in my head the first urologist I talked to chirpily recommending not only a TURP but also a suprapubic catheter (a tube from my abdomen draining into a bag, like the Foley), without giving me any idea of the seriousness of the risks to a tolerable lifestyle. Why he recommended the suprapubic catheter when TURP was supposed to treat the symptoms, I still don’t know. All I do know is that if I had taken his advice, chances are very good I would be suffering the depressing, emasculating and debilitating effects of “dry orgasm.” I might also have erectile dysfunction and possibly be wearing a diaper as well. Instead, I lead a relatively normal life with the minor inconvenience of “intermittent self catheterization.”

So: Advice to LUTS sufferers: do your own research, and don’t believe everything your doctor tells you. Get a second opinion from a disinterested party. If you need any further convincing on this, try putting “unnecessary surgery” in your favorite search engine (DuckDuckGo) and spend a few minutes reading the results.

Advice to urologists: when you breezily recommend a TURP, have you really considered the effects it is likely to have on your patient’s life? Can you imagine if you yourself, not to mention your partner, had to endure the likely side effects for the rest of your born days? Is it that you think that once people are over 50 they don’t do sex anymore? At least if you are going to recommend a TURP, let the poor bastards know clearly and graphically what it could do to their lives. Send them along to one of those bulletin boards to read the comments of men who have actually had the procedure. Explain that the chances are very high that they won’t be able to enjoy sex as much, or at all, any more, and give them the odds on all the other risks. Maybe they will prefer the side effects to the LUTS and go ahead with the TURP, but at least tell them about less drastic treatments, like PAE, that they might like to try first, and give them all the information they need to make the decision for themselves.