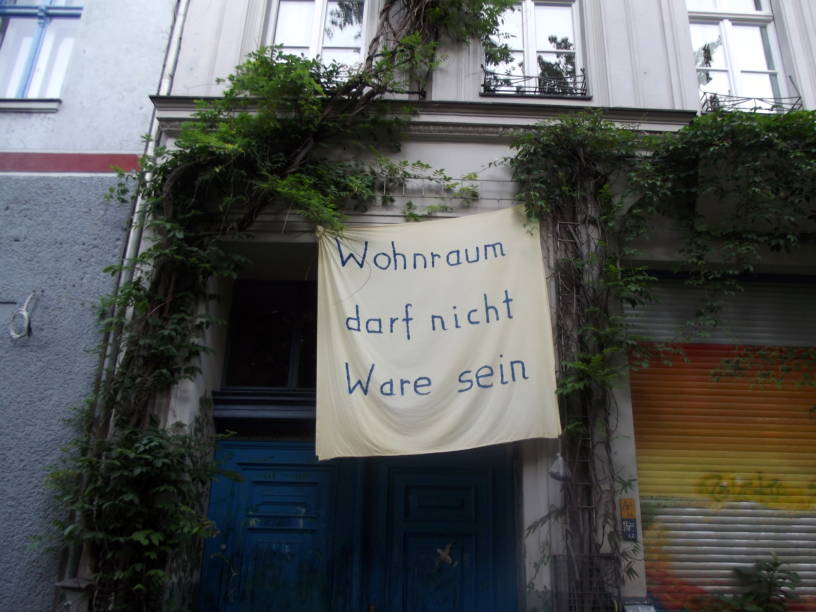

On a corner on Rigaer Strasse, a flashpoint in confrontations between demonstrators and police, a vast banner hangs. Rent 2009: 700 euro. Rent 2019: 1700 euro. Throughout the city, on the borders of rising prices, banners hang from windows. A common refrain emerges: Wir bleiben alle.

We’re staying.

Berlin enjoys some of the strongest rent control in the world. In 2015 a ‘rental brake’ was introduced that capped rents at neighbourhood-appropriate rates and tightly controlled the rate of increases. But in 2017, rents rose faster here than in any other similar sized city in the world, while wages remained static.

“I’m afraid Berlin will turn into London,” says Oliver, an activist with Mieten Wahnsinn, a group that coordinates mass actions for local housing collectives and activist groups. He means expensive, he means gentrified, a city where access to a high quality of life is contingent on having a desk at Google.

The city has so far managed to escape the worst of the housing crisis that has affected cities like London, Dublin, and New York. But Berlin sees its future in them, and activists recognize that dramatic action will be required to avoid the same fate.

“Ten years ago, we were paying 250 euros a month,” Oliver says. In 2009, you could expect to rent at just 6 euros per square meter. Now, it’s just over 10. In some traditionally working-class neighbourhoods, it’s over 13.

Last year, a network of activists proposed a solution: Enteignung (“expropriation”), a cap on property ownership at 3000 units within the city of Berlin. Any entity possessing more than that will have the ownership of its excess properties transferred to the city. If this proposal becomes law, it’s estimated that 243,000 apartments—fifteen percent of the city’s rental units—would become the property of the government overnight. They would be controlled by a new, democratically-elected housing council “with no profit motive,” formed for the purpose. The Senate would have extraordinary powers to circumvent any sell-offs or shell companies, having conducted a comprehensive survey of property ownership in the city long before the passage of the new law, which would exclude existing renter-owned collectives and exclusively target for-profit property enterprises. If a referendum passes in support, the Senate will be obligated to draft legislation in line with its demands.

A vast network of activists is advocating for this legislation—known catchily as “DW & Co Enteignung,” after the protest group that targets a particularly reviled property company—throughout the city. Berlin has a strong history of housing activism and tenant collectivization against property speculators and the centre-led government, which favours privatization. A few years ago, a similar citizens’ movement successfully protested the redevelopment of a disused airport, prompting a referendum to transform it into a giant public park instead. Just last year the residents of Kreuzberg, fearing further gentrification, protested a proposed Google headquarters so fiercely that the tech giant relented. This kind of power doesn’t come easily; DW & Co Enteignung spokesman Thomas McGath pointed out that its influence is the result of at least thirty years of dedicated community organizing.

At the turn of the millenium, Berlin’s population was falling; the Left-Green city government, expecting that trend to continue, sold off thousands of units to property companies. But as the city recovered from a brutal 20th century, new people began to arrive. Most of them came from other parts of Germany, from civil servants working in the new capital to anarchists who formed famous squats in the empty spaces left by the Wall. They were joined by a wave of EU citizens, including the many artists and freelancers who’ve come for the scene and the affordability. The government may not have anticipated it, but investors watched as the population and cultural capital of the city swelled in tandem with a quietly burgeoning tech industry. Demand rose and within a few years, private ownership had followed suit, and rents began to inch their way up.

To protect renters against creeping gentrification, the government introduced the Mietpreisbremse, or rental brake. ‘Local comparative rates’ were set for every neighbourhood, indexed to existing rents. Increases were limited to ten percent of this standard, and only when there was a change of tenancy.

But it didn’t work. Landlords in Berlin became expert at finding workarounds. The rental brake may have protected individual tenants from sudden rent hikes, but on a city-wide scale it was rendered entirely useless. Deutsche Wohnen and other large property firms were big enough to own whole neighbourhoods, giving them control over the local comparative rates. They then prioritized short-term tenants, which would allow for more frequent rent hikes. The rental brake’s loopholes also stipulate that landlords can add 11% of the cost of building improvements to monthly rents—permanently. Since tenant approval for improvements is not required, landlords began adding luxury improvements wherever they could, squeezing renters for more and more cash until they could no longer keep up, at which point the empty, refurbished space could be newly marketed as a high-end property.

Finally, the rental brake lacked teeth, so that many complaints against abusive property owners resulted in a mere verbal warning, and landlords were often permitted to keep the extra money they had unlawfully extracted from tenants. Landlords soon realized that their offenses would go effectively unpunished. Their workarounds got results.

Rents in Berlin rose faster than ever before in the immediate aftermath of the new laws’ passage, and the city realized it would take something more to address the crisis. But what?

My parents’ generation left my home city of Dublin in droves, for want of jobs. Between their generation and mine the situation inverted: Now, the people I meet in Dublin less often want for jobs, but find they, too, must leave the city in order to afford a place of their own.

Among Dublin’s architectural treasures are its many Georgian buildings, fine redbrick houses and mansions from the 18th century that surround parks and line streets in the city centre. They housed the professional class and aristocracy in the city’s heyday as one of the capitals of the British Empire. As Ireland’s economy disintegrated in the early nineteenth century, they became squalid and overcrowded tenements. By the 1960s they’d been converted back into houses and apartments for the middle class, though the centre was seen as undesirable, and so prices remained low. But as the pendulum swings back and Dublin’s fortunes rise, canny landlords have once again learned to pack these houses with as many beds as possible.

On my street, a former living room can now house sixteen people, and real-estate listings include such absurdities as beds in bathrooms, and a family home shared by forty people at five hundred euro a head. Ruthless scams abound, such as fake sales, whereby tenants—evicted by landlords who claim their building is being sold—find their homes right back on the rental market at an inflated price.

Homelessness is at an all time high, a factor attributed to the rental crisis. Every time I go home, a new headquarters has been built, and the number of people sleeping rough has visibly increased. Dublin and Berlin (and New York, San Francisco, Amsterdam, Nairobi, Taipei and Lagos) are rich cities, but they are not healthy.

Cities are nothing but places to live. They cannot survive being governed by some other set of priorities.

It’s not uncommon for people here to pin the blame for rising rents on newcomers to the city, though the far-right in Germany has largely avoided the housing debate, apart from the occasional attempt to blame refugees. More commonly and across the political spectrum, there’s a degree of resentment towards more privileged newcomers, that is, middle-class Westerners drawn to the city by the arts and tech scene, as represented by the sudden omnipresence of the English language, and the replacement of comfortable, affordable neighbourhood institutions with bourgier new businesses.

Blame tourists, blame AirBnB, blame immigrants, blame students, blame foreign buyers, blame fecund citizens, blame medieval architects, blame hipsters, blame anybody. Housing is complicated, we’re told, and delicately specific to each town and city. But in every city, the same uncomplicated fact emerges: The privileges of property owners remain essentially untouched.

“There’s no reason that someone else moving into your city should cause your rents to double,” McGath points out. In Berlin they’re skipping that debate and targeting the source of the problem: landlords. Merely executing the will of the market, landlords are “rationally” compelled to respond to the influence of speculators, wealthy newcomers, and AirBnB-ers by driving rents upward. This system enables landlords to hold whole cities hostage. But rent doesn’t rise by itself; the landlord raises the rent.

Intense population spikes in urban areas are a global problem that will stretch the limits of design and engineering; all the activists I’ve spoken with are agreed on this. But in cities with a high influx of new residents, building affordable units is severely hampered by what economists would call “opportunity cost,” income lost by failing to take advantage of an overheated market. The prospect of guaranteed wealth is irresistible to developers and investors, who aren’t about to leave millions in profit on the table.

It takes years—many news cycles—for new buildings to actually appear, during which public offices change hands and a city can be lulled by the imperatives of capital into believing that housing is a population problem, a “natural” problem the cause of which is the people affected. Under that interpretation, it’s no one’s fault as such, and the solution in the long term is for people to have fewer kids or better still, just leave.

So sure, build more quality living space and reliable transit systems to get to it, you have my blessing. But unless a resource stays in public hands, if there’s a dollar to be made, capital will come for it eventually. Zoning reform, the North American go-to for housing solutions, simply avoids the central issue facing renters: The profit motive of their landlords. While opponents to the proposal maintain that there are lighter-touch solutions to the housing crisis, groups like Mieten Wahnsinn are clear that expropriation is the only way to decommodify housing. Unless you step in and partially nationalize the housing market, the only thing that will stop prices going up is the city becoming an undesirable place to live. How’s that for a policy goal?

There’s heavy resistance to expropriation within Berlin, centred around the liberal government, who favour either the strengthening of existing laws or simply maintaining the free-market approach. Mayor Michael Müller, for example, proposed the formation of a joint committee comprised of government officials and representatives from the property companies to oversee the situation. “It reminds me of when Obama said Wall Street would regulate itself,” says McGath. “Look how that went.” The Left and the Greens have expressed support, but the centre-left SPD are still looking for a less radical solution. Commercial real estate giants JLL claim to be unconvinced, the former referring to the proposal as “fantasy.” As for the landlords themselves? Deutsche Wohnen CEO Michael Zahn appeared in a joint conference alongside activists and industry leaders and proclaimed that his company “will not be expropriated.” Germany, he noted, is not a banana republic.

Laws on private property differ across the world, but most come down to the same principle: everybody has an inalienable right to their own stuff, but if the stakes are high enough the government can take it. Article 15 of the German Constitution states that while property is “guaranteed,” its use must also serve the public good.

In the EU, similarly, the declaration of rights maintains that every person has a right to his own home, and the constitution adds that all of us have a right to the peaceful enjoyment of all of our possessions, unless we’re a threat to public safety. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights says the same; you’ve got a right to enjoy what you own, but only “subject to the general interest.” Such laws are deliberately vague, designed for reiterative interpretation and flexibility. The housing crisis is not so clear-cut; it’s not an all-out war, nuclear threat, or mass extinction event: It’s just an urgent problem facing millions of people in their daily lives. Increasingly, it appears that rights and protections designed to apply to disaster scenarios and authoritarian nightmares may not be up to the task of dealing with creeping pressures of unrestrained late-stage capitalism.

Activists have pointed out that expropriation laws are in fact put to use regularly. Private interests are happy, they say, with the seizure of land for profitable public works such as highways and airports, and large-scale resource extraction (in the Anglophone world, this process is known as “eminent domain.”) They’re not keen to provide full compensation to property owners affected by Enteignung who already have so much, especially seeing as the estimated market-value compensation of the program couldreach 40 billion euros. The constitution notes that compensation must be balanced against the public interest, something DWE claims exempts them from the need to pay the landlords in full.

Everyone I spoke with in Berlin was eager to pre-empt claims that the bill is needlessly extreme, or a dangerous step towards authoritarian socialism, a concept that looms heavily over a city with recent memories of the Wall. Rather, it’s a simple fix to reorient infrastructure towards a public good in a time of need, and backed up by precedent not only from Germany but across the world. Helsinki, for example, has been quietly demonstrating the feasibility of social alternatives to housing policy, massively reducing homelessness with a system of nearly unconditional guaranteed housing.

But Enteignung has a long way to go still. First, if the city council accepts the proposal, they’ll send it to the Senate, which will draft a law reflecting the demands of the electorate. If the city council reject the proposal, supporters will have to collect 190,000 signatures in order to trigger a referendum. If that passes, it will go to the Senate—and from there, be open to appeal by the landlords themselves.

As time goes by the bill’s proponents have gained confidence. Both activists and the Senate have commissioned analyses by independent legal scholars and all have concluded that such a law would be constitutional, but even so, landlords will still benefit financially from delaying its introduction.

But if the law is written and if it survives appeal, it could set a precedent for transforming housing as we know it, curtailing the market’s power in order to redefine housing as an essential public good.