According to the dream interpreter, Ibn Sirin, it was Adam who witnessed the first visions on earth. Figures and shapes, soft and nocturnal, filled the mind of the sleeping prophet. As an act of mercy from God, the first dream took form: the face of Eve.

In 1980, the Syrian filmmaker, Mohammad Malas, would recount this story while entering the bounds of Shatila Refugee Camp.

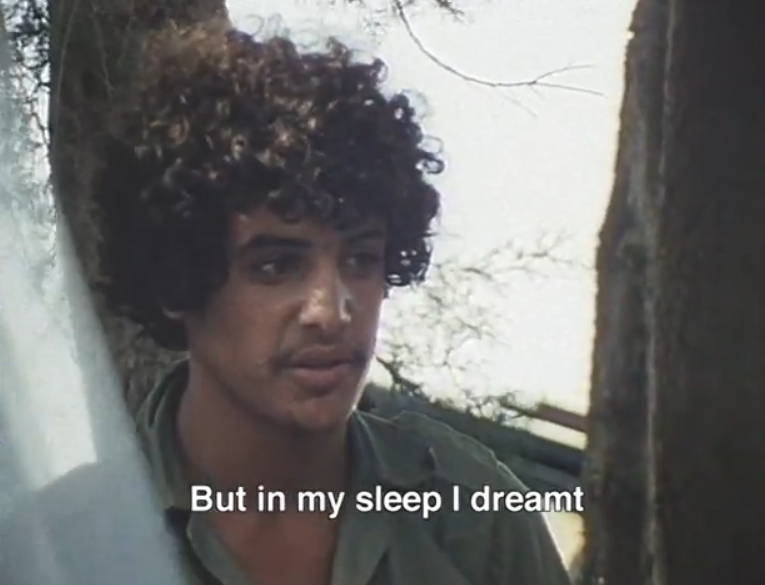

Malas was in the planning and research stages of his seminal documentary—Al-Manam (‘The Dream’)—when he first visited the camps. In creating the film, he recorded the dreams of over four hundred Palestinian refugees in Lebanon. After its release, Malas published a diary account of these years. In remembering Al-Manam, Malas’s diaries help us to better understand one of the most haunted works of Arab cinema.

Viewers of the film are cursed with a particular foreknowledge: They know that mere months after these interviews took place, under the light of Israeli flares, Kataeb genocidaires will enter these camps. One may occasionally forget this fact in the tenderness of the film’s images. But the knowledge cannot be entirely banished or forgotten. One will remember. The tender life of one’s heart will move and petrify at different intervals. There is no answer, but one still asks: what are we to make of these images? The visions and dreams of those thereafter exterminated?

Walter Benjamin, quoting Moritz Heimann, considered the following statement: a “man who dies at the age of thirty-five [is] at every point of his life a man who dies at the age of thirty-five.” What this sentence revealed to the late philosopher-refugee was that fatal claims, which “make no sense [in] real life” or in life as it unfolds, soon “become indisputable [in] remembered life.” (Sami Khatib notes this too is how we have come to narrate Benjamin’s own life in light of his suicide.) Massacre looms “at every point” in the film.

The pain of viewing Malas’s documentary is somewhere in this tension: seeing dispossessed and delicate visions unfold in front of the camera, all in the consciousness, the prescience, of a genocidal horizon.

Yet, this was not the film Malas had intended to make. He did not seek to collect accursed artifacts. He sought, instead, to capture life and beauty in onerous conditions. An unsettling idea now, but from 1980 to 1981, it was within the pale of the filmmaker’s expectations to enter Shatila and Sabra in search of hopeful things. This aspirational commitment is captured in his diaries and evinced in the very subject of his film: dreams.

One of the first dreams recorded in Malas’s diary comes from a refugee who describes an account of his own death. Dreams of the afterlife are common in Al-Manam. The dreamer is reunited, in another place, with his late father. “No one told me you died,” remarks the father. The son clarifies his dream-state to his father: “I am dead but alive.”

The father exhorts him to choose life: “Your time will come later. May God make you happy.” At the end of the interview, the son ruminates and struggles for a final word to give Malas.

“A dream is a merciful thing,” he concludes.

In dreams, Palestine is often cast in the rosy hues of memory. Visions of reunified family life, episodes from childhood, the boredom of an Arabic literature class, dipping pieces of bread into olive oil, and ancestral farmlands no longer fractured by military checkpoints. In the middle of Malas’s film, the liberation radio croons: “Memories come and do not hurt.”

This Palestinian dreamscape, however, is not a ‘utopia’ for two reasons: First, ‘utopia’ implies the nonexistence of what is in fact a real place. Utopia is not just eu-topos, ‘a good place,’ but also, ou-topos, ‘no place,’ in the deliberate pun of Thomas More. Palestine is a real space on earth. This must not be forgotten. The Palestinian struggle, as a colonial struggle, harkens to Frantz Fanon’s assertion of the “first and foremost[ness] of the land.” In dreams, there are endless markers of place, and a geography of the transfigured: “Al-Nameh,” “Jaffa,” “the village,” “Haifa,” “Majadleh street,” “Acre,” “we cry for the land,” “the East,” “Saffah,” “home.”

In his 1967 lecture, “Des espaces autres,” Michel Foucault proposed an alternative to ‘utopia,’ the ‘heterotopia.’ The late French philosopher described heterotopias as real and existing spaces. But at the same time, they are ‘heterogeneous’ in experience. They are punctured and sacralised by spatial functions, memories, and the rites of time. Heterotopias are spaces ‘haunted by [fantasme]’: a word often translated from French as ‘fantasy.’ But also semantically connected to a more spectral vocabulary: ‘phantasm,’ ‘phanthom,’ ‘fantasmatic.’ This comes close to capturing the painfully real, spatial, and damaged dreamscapes of Palestine among the refugee-interviewees of Al-Manam.

Second, ‘utopia’ does not capture the Janus-faced nature of the film’s testimonies. These are dreams and nightmares both. (Traum is the common root from which we derive both ‘dream’ and trauma.’) In one, an Israeli bulldozer stalks a woman down a street. An aerial bombardment so violently shakes the foundations of the home in a dream that the dreamer awakes to find her radio has fallen and shattered in real life. Many relate nightmares of the Tel al-Zaatar massacre. One dreamt of seeing Shimon Peres among the killing fields. Many of the refugees in Sabra and Shatila had survived this atrocity in 1976 only to fall victim to one still looming. Walls, borders, and the carnival of occupation. What kind of ‘utopia’ would this be?

In Al-Manam, the dream haunts us with impossible visions, impossible times. Dreams, to borrow a phrase from Benjamin, represent the “open air of history.” Many are political. Many are intimate. In a shoemaker’s dream, Gamal Abdel Nasser points his finger toward Palestine and trumpets the call for its war of liberation. In a barber’s dream the late Saudi monarch, Ibn Saud, arrives to meet the Palestinian leadership. In a young guerilla’s dream, Shaikh Zayed of the United Arab Emirates is told of the young man’s honorific heritage: “This man is Palestinian.” A tired Abu Ammar (the nom de guerre of Yasser Arafat) finds refuge in the dreamer’s home, lays beside him in bed. Dreams are ways of nurturing political optimism—here, the bittersweet fantasias of Arab nationalism.

The most affective stories, the most merciful visions, are those about loved ones. These are the dreams that relay memory or the restoration of family life: generations brought onto a common stage, martyrs and missing sons, late mothers and fathers. Malas asks one of his interviewees to clarify a strange discussion between the dreamer and her displaced father. Where did this take place in the dream?

“In the afterworld, of course.”

Three decades since its release, Al-Manam continues to entangle us in the webs of memory, dream, and trauma. Echoing the oneiric stories of Palestinian refugees, the radio plays an Umm Kulthum song: “Our loved ones have once grieved for us.” There is a semblance between, on one hand, how we venerate Al-Manam and its dreamers, and on the other, they their loved ones.

“Do they remember us, or have they forgotten?” Umm Kulthum sings.