When they were 14 years old, during Monday first period, Nadja Klier and her best friend Anna wore the blue shirts of the communist youth organization, the Free German Youth, to chant “Freundschaft” (“friendship”) in the courtyard and salute the East German flag. They spent much of the rest of their time reading books and going to parties at the youth club, where the DJs played the mandatory portion of East German songs at the beginning and saved the hits, like “Don’t Go” (Yazoo) and “Get into the Groove” (Madonna) for the end.

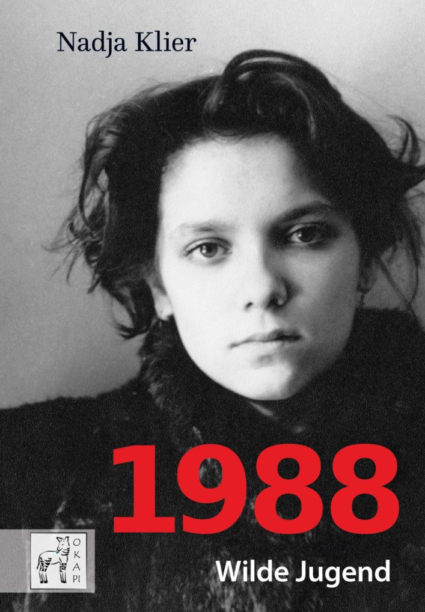

Once, Klier writes in 1988: Wilde Jugend (“Wild Youth”)—the recently-published memoir chronicling her adolescence in East and West Berlin, from 1986 until the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989—Anna rang Nadja’s doorbell in the middle of the night, hoping to sleep over, and Nadja didn’t answer because of an argument they’d had earlier. Anna had always depended on sleeping over at Nadja’s after going out; her mother was very strict. They didn’t speak for three entire weeks after that; later, Nadja lied to Anna that she’d been out of the house that night. Feeling guilty, she even wrote this false version of the story in her diary.

So it was a dramatic time, in a way that will be familiar to anyone who’s ever been a teenager. “You are in love for the first time,” Nadja told me recently, “and you go for a walk together and he tells you something great, and then you have this song. And three weeks later it’s over and it hurts you so much, because you wanted to stay together and every time you hear this song you will think about how it could have been, how it could have continued.”

In January 1988, Nadja and her mother, the stage director and leading civil rights rights activist Freya Klier, were suddenly exiled by the East German government.

Authorities had begun to arrest dissidents weeks earlier, fearing a new alliance between those who wanted free travel, and those who wanted to reform the German Democratic Republic from within—and their rumored plan to disrupt a parade in honour of Rosa Luxemburg with “unauthorized banners,” some of which would quote Luxemburg’s words: “Freedom is always the freedom to think differently.”

Freya and Nadja had already been hearing footsteps from the attic of their shared apartment for some time. If Freya wanted to talk openly, she would suggest going for a walk outside. Nadja wrote in her diary and tried not to say the wrong thing to friends over the phone, in case it was being tapped. Two men with briefcases, whom Anna described as “bodyguards,” followed her to school and to parties.

“If I get arrested, there will be someone who will take care of you,” Freya told her daughter. She didn’t tell her that the secret police had already tried to assassinate her and her husband, the banned singer Stephan Krawczyk, with a nerve gas attack in their car.

On Nadja’s last night in East Berlin, she and Anna lay in bed crying and saying everything that was nice about knowing each other and being friends. “We repeat and affirm all of this one hundred times, as if one of us will die tomorrow, so that the person who stays will not forget it,” Nadja writes in Wild Youth. They swapped diaries: Anna had started keeping a diary too. “It was one of the things that changed after meeting Nadja.”

Right up to walking Nadja to the car of a priest, who would drive her to the border, Anna says, she believed that it was a nightmare they would both awaken from. The West German press would initially report that Freya left willingly. But Freya and Nadja hadn’t wanted to leave. For Anna, “It was the first time in my life that I was confronted with such an injustice, against which I was completely helpless.” As she watched them drive away, she thought: “That’s it. You will never see her again.”

To be a teen in East Berlin in the 80s meant knowing that East Germany wasn’t working, Anna tells me. It was embarrassing to walk through streets lined with crumbling houses hung with flags imprinted with the East German coat of arms—a compass and hammer encircled with rye. If you saw a queue of people lined up outside a shop, she says, you’d join it without knowing what exactly was being handed out.

In 1988, it was standard procedure for the Communist Party to fight a protest movement by arresting and expelling its symbolic figures. But the arrests of Freya Klier and Stephan Krawczyk—who had been putting on underground performances in churches across the country—along with those of around 100 other dissidents, only sparked further protests, marking the prelude for the revolution that would come in 1989.

In East Germany, your future was über-determined by whatever the state determined to train you in. If you studied a subject like teaching, you weren’t allowed to then become a secretary, because you’d be overqualified. “We wanted to be individuals,” says the artist Cornelia Schleime in the documentary Ostpunk: Too much Future, about punk in the GDR. In her early films, which showed women tied to doors and walls, Schleime said, “I was looking for images where there was this feeling—you were in a jail—of the GDR itself, but also that you couldn’t really actualize yourself in it.”

Anna started her apprenticeship after she finished 10th grade. She’d also applied for acting school, but barely felt motivated to learn the lines. “I didn’t have a dream,” she says. People her age were fleeing across the border or applying to emigrate to West Germany and didn’t know why. “The main thing was to get over there.”

In West Berlin, Nadja enrolled in one of the few high schools in the city that taught Russian. Many kids came from East Germany, from Yugoslavia, from the Soviet Union. She’d heard before that there were more books, more products in West Berlin, that you could just buy a plane ticket and fly anywhere.

“When I arrived there and it was really like that, it overwhelmed me,” Nadja says. On her first day, she went to the supermarket and spent 20 minutes in the dairy section, reading every Onken yoghurt label. “I couldn’t decide which one to try first.” She ate all of them. “I didn’t feel good.”

“I stood in newspaper stores,” she says. “There were hundreds of magazines, and I read the magazines there because I couldn’t buy them all. I soaked them up like a sponge.” She especially liked the advice columns, even though the questions (Does he love me?) were similar in every magazine.

courtesy of the author

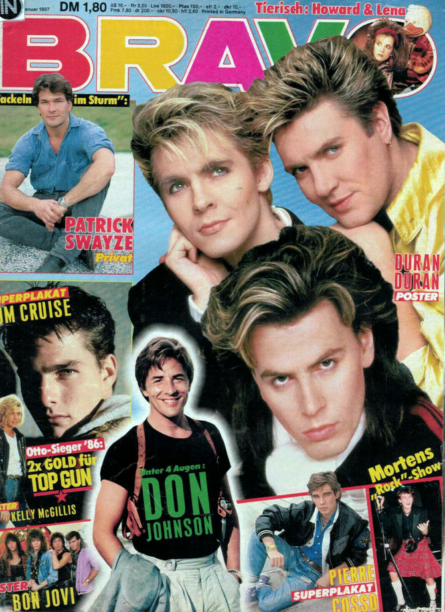

courtesy of the authorWhen she’d lived in East Berlin, the western girlfriend of Nadja’s father would sometimes visit and bring her the Bravo, a ultra-popular teen magazine stuffed with bright posters of Madonna, Bronski Beat and Cyndi Lauper. From the late 60s onwards, a columnist with the pseudonym “Dr Sommer” took on the task of answering the young West German Republic’s practical love and sex questions (“Does it also hurt the boy when he sleeps with a girl for the first time?”, “My mom greeted him naked, so he broke up with me”). Dr Sommer’s comments on masturbation initially shocked West German authorities into twice classifying the mag as “harmful.” Nadja sold each page on to her classmates.

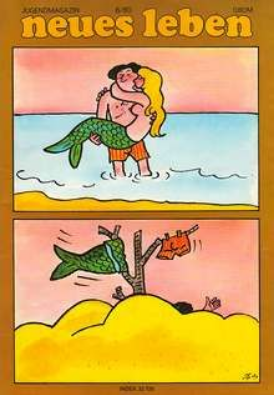

Of course, the Free German Youth published a teen magazine too. It was called neues leben and was mainly available from behind the counter of East German stores. In addition to articles in which teens confessed to petty crimes committed by themselves and their friends, the magazine employed a professor to dish out sex and relationship advice. But supply was limited.

At her new high school, Nadja quickly found a new group of friends. Together they’d go to parties at her music teacher’s house, where you could smoke and drink and talk for hours. Just one of them, Julia, was from the West: “the only West friend in the clique.” The boys in their class would say, “don’t spoil our Julia!”

What did they mean? “We were just much more direct,” says Nadja, about herself and her friends. “We were faster. There wasn’t so much hmm yeah, tomorrow a date, and then 1, 2, 3. If we felt like kissing on the first time, then we did that. If I felt like saying: I want you, come home with me, then I did that.”

There were various theories and cliches about sex in East Germany vs. West Germany, though Nadja says the generalizations weren’t absolute. But some of the kids from the West, she says “didn’t seem so enlightened” when it came to sex education. And they insisted on using changing rooms to undress.

Because the school had such a high number of kids who came from Eastern Bloc countries, though, “Somehow it didn’t really play a role,” says Claire, a school friend of Nadja’s, whose mother was in a civil rights group with Freya Klier. “you were friends with the people you liked, and not because you came from one country.”

Generally, though, she says, “I felt like the Westler were definitely more bougie that Ossis. And later they turned out to be a lot less political.”

At school, the new kids from the east would have to repeat whatever year they’d just finished back home. For Britta, another former classmate of Nadja’s, the first months in a new class where everyone else was one year younger and from west Germany were “so awful.”

Britta’s family fled to West Berlin when she was 15. She sold off her belongings, worried about her mother being arrested, and kept the whole thing secret from her friends.

“They were reading these weird magazines about makeup and clothes, having these weird conversations,” she says of her new, younger western classmates. “I felt like a grandma.”

“There is only a before and an after,” Britta, now a German teacher, says of her emigration. A few years ago, when she wanted to prepare a lesson about about her life in East Germany, she choked up. “I felt all these pent-up emotions, I had to postpone.”

Magazines like Bravo and Mädchen (Girl)—“terrible magazines today,” Nadja says—weren’t the only platforms for seeking advice from people who weren’t your parents. Later, in the evenings, she would listen to radio shows, “where people could call and pour their heart out and other people listened,” she says, “you hear how people are doing or that they are lovesick or that they’ve been dumped, or that they failed or messed up at something. they can call anonymously and talk about it completely in peace.”

Meanwhile, her mother Freya spent the first few months in West Berlin giving interviews. Some of the civil rights groups back in the East had distanced themselves from her. “They would have preferred if I’d stayed in jail,” Freya Klier said later, “then they could have used me as a martyr.” She started a new campaign, to ban the production of ozone-depleting CFC gases.

When Nadja arrived at school on the 10th of November 1989, everyone was in an uproar: The wall was open. In first period, the teacher still made the class write an English exam, and then school was out. Immediately, Nadja took the train to the border. Anna was working at the Berliner Ensemble theatre, doing an apprenticeship. Nadja ran the final steps.

“We spent a lot of time together after the wall opened up,” Nadja says, “But then we sort of split up for a while. She couldn’t deal with my attitude. If you live in the West, then you are consuming a lot, materialism and stuff. I sort of slipped into the superficial. I wasn’t interested in things, I wasn’t in a politics society.”

Anna says she was annoyed that Nadja was constantly snacking: “I thought: why are you always eating?”

Today, Nadja works as a photographer and has started speaking at schools about East German history. “I’m becoming my mother after all,” she jokes. Anna is an opera singer. She decided to study singing after her boss at the Berliner Ensemble noticed her humming under her breath and invited her to an opera concert. When they meet up now, they talk about their jobs, their kids, their husbands.

Anna says her first reaction to the book was: “Who is this cool girl that she is describing, that’s not me!” Back then, aged 14, she says, “I felt self-conscious.”

Nadja based much of the book on the diaries they once shared. Yet some of the dialogue, Anna says, “sounds more like out of Sex and the City than how two girls from the east would have talked.” Nadja also wrote that Anna was top of her class. “That’s not true!” Anna laughs. “That was her!”

“I think she was half joking about Sex and the City,” Nadja says.

In the beginning of Wild Youth, Nadja describes meeting Anna for the first time. Anna introduces herself to a group of kids at the sports center and asks them if they know the band The Communards.

“Anna briefly looks around to see how many people might hear her,” Nadja writes, “and starts to sing ‘Don’t leave me this way,’ with a crystal-clear but also full and soft voice. She sings at a high pitch, without wobbling and without a German accent.” At the end, all the kids applauded.

“It was an unbelievable moment,” Anna says. “Me thinking ‘ohh she is great,’ and then realizing that she thought I was great. The way she looked at me was such that I just thought, Wow.”

Nadja had tried once to go back to East Berlin to see Anna before the fall of the Wall. But her applications to travel kept getting rejected, until at last she got a one-time one day visa. She made plans all week, bought gummi bears, chocolate, posters and books as gifts and planned to surprise Anna after school. Then on the day, Anna wasn’t at home and her mother—who later claimed she’d wanted to protect Anna from more sadness—lied to Nadja that she didn’t know where Anna was.

In September this year, as part of an exhibition series about “insider views” into the GDR at the Pankow Museum in Berlin, Nadja Klier read this scene from Wild Youth to a packed room. Then she asked Anna to stand up in the audience. Both women had tears in their eyes.

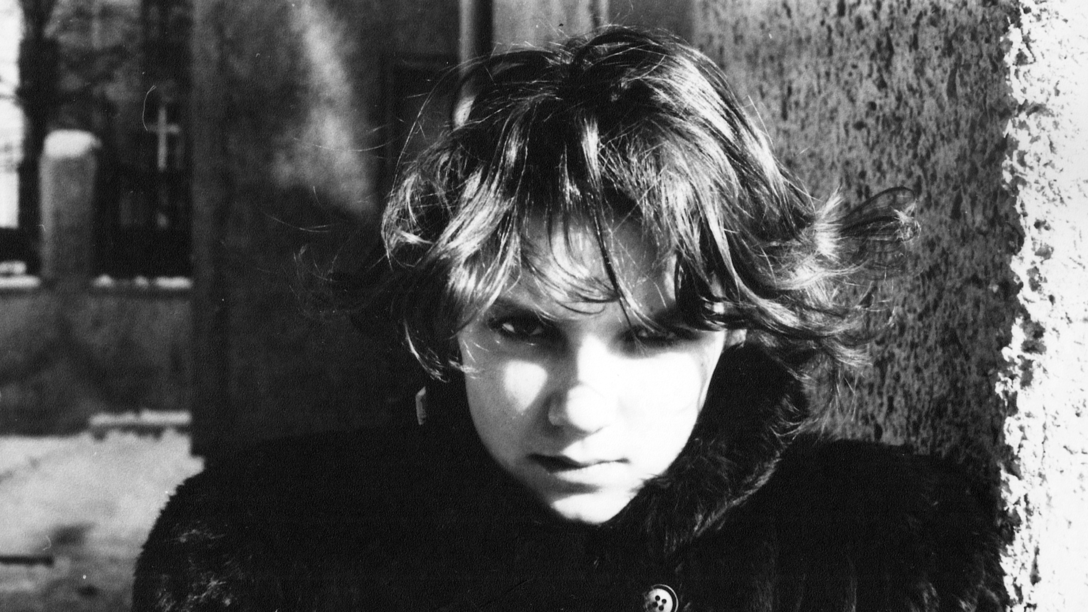

photo courtesy of Nadja Klier

photo courtesy of Nadja Klier