As a single mid-30s man severely lacking in domestic skills I rely on my local food carts to provide me with a semblance of home cooking. Within a five-minute walk from my front door there’s a parking lot oasis—one square block stocked with 21 different semi-permanent little takeout restaurants: fast Mexican, Indian, Thai, Ghanaian, Korean and Middle Eastern, generally known as the “PSU food carts,” owing to their proximity to Portland State University. The majority of these places are family owned and run, literal mom-and-pop businesses. The carts (really, more like small shacks than carts) are descendants of the thermopolia, a ubiquitous fixture of Roman life. A small stand offering ready-prepared foods, providing convenience to city dwellers.

Recently a new and radically different kind of cart appeared in my local lot. It was built out luxuriously, with high-quality infrastructure: dedicated power lines and sewage, a private port-a-potty. An inside wall bore a neat row of little android tablets. Most intriguingly, the cart lacked any signage whatsoever, or any indication of what kind of food would be served.

There was only one person inside. I asked her what was on the menu. She explained to me that they would take no orders in person; this cart’s menu was only available through delivery apps. That is, the food cooked here could only be ordered via app. Hmm.

courtesy of the author

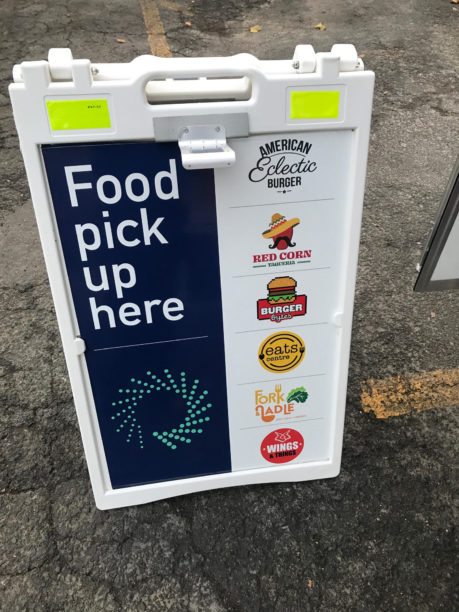

courtesy of the authorBy the week’s end, signage had appeared, a big blue arrow stating, “Food Pick Up For Delivery Only” with a sandwich board listing the names and logos of six different restaurants: “American Eclectic Burger” in a refined font, promising sophisticated fare in comparison with its slacker cousin, “Burger Bytes”, rendered in an 8-bit logo. “Red Corn Taqueria” promised Mexican-esque food, their logo a bizarre and faceless approximation of Emiliano Zapata. And finally, a strange blue spiral, with an interior of closely compacted dots swirling outward to a sketchy outer rim, the visual approximation of a “widening gyre.”

The next day a new sign appeared, promising pick-up for Rachael Ray’s menu; Ray recently made a deal with UberEats. This odd little cart was mysteriously and disquietingly associated with all of these businesses. Who was behind all this? What was this business model?

When I asked inside I was told it was a parking lot company, the biggest in America. And they gave me a name, “REEF Technology,” to go with the widening-gyre logo. After a few minutes’ research I felt ill, a free-floating unease, almost nausea. The absurdities of our global economic system had arrived, via mysteriously luxurious Trojan food cart, in my neighborhood.

Screenshot: reeftechnology.com

Screenshot: reeftechnology.comREEF Technology already owns “a growing network of 4,500 parking lots in the top 25 markets across North America.” Hidden in the pablum of their About Us pitch, the company promises innovative and profound changes to the neighborhood parking lot. They intend to transform parking facilities into “ecosystems that connect to the goods and services that keep us moving forward in a sustainable and thoughtful way.”

Aside from the obvious objection—the only way to “transform” the parking lot into a genuine ecosystem would be to remove the asphalt and let nature take its course—it appears that a core element of their business model is spying or, more in the modern phrase, “surveillance capitalism.”

REEF boasts of its ability to gather data using tools like automated License Plate Recognition in the hope of providing “invaluable consumer data for landlords to optimize property value.”

Theirs is a vision of parking lots full of scooter docks, autonomous vehicle charging stations, gleaming rows of trailer-sized “cloud kitchens” like the new one near me, where faceless contract workers cook food ordered via app, with swarms of delivery drivers (and someday, drones), in a space defined by constantly recording cameras performing endless facial and license plate recognition, crammed with packet sniffers pinging smartphones. A hub of surveillance, propped up by limitless amounts of venture capital, in the service of “neighborhood transformation.” No kidding.

REEF Technology is also part of SoftBank.

No other company defines the sheer frivolity and unsustainability of our current market moment like SoftBank. It’s a Japanese conglomerate and investment bank, lately funded by the Saudi sovereign wealth fund, and notorious for its many spectacular reversals of fortune. The company made WeWork into a byword for excess, founder worship, and lack of a plan. Softbank is a neo-Gilded Age concern, today defined primarily by its string of multi-billion dollar losses based on “losing to win” monopolistic ambitions. Yet there always seems to be more money flooding in. This is the absurd reality of the past decade: So much money at the top, and nowhere to put it.

The business environment that existed on this block for at least a decade was simple. There were tons of hungry students and office workers in a half-mile radius. They would leave their homes or work and buy tacos or gyros or biryani directly from the carts, and head back home or to the office to eat. A person (me!) who wanted food could leave their apartment, walk for five minutes, choose from among many options, pay seven dollars, wait five minutes, walk back to their apartment and enjoy a burrito. The owner and operator of the restaurant might make three dollars’ direct profit from the sale.

Now a megacorporation seeks to remake this environment as an “Ecosystem.” This corporation was partially funded by a Japanese investment firm with $45 billion in investments from the Saudi Arabian government, and partially subsidized by the sovereign wealth fund of Abu Dhabi. A series of proprietary algorithms, fueled by vast amounts of invasive data-mining, came to the conclusion that people living within a certain radius of a certain area were most likely to purchase hamburgers at certain times. Two different “ghost” burger concepts were then branded to create the illusion of choice: a sophisticated eclectic burger and a funkier “byte burger.” The foodstuffs would come from the same suppliers and be prepared by the same people working in the same cart. The Ecosystem proposes that a hungry person will log on to an app, choose their desired burger, and a contract chef working in the ghost kitchen will prepare the food, which will then be picked up by another freelance contractor who will deliver the algorithmic food.

The reviews are in, and these meals are neither very good nor very affordable. How could this system possibly be efficient or profitable? It’s not. It couldn’t be. The investors, the developers, the sovereign wealth funds, the algorithms and the banks—all the intermediaries responsible for sloshing great amounts of money between each other for no real purpose—all of them want to get in between the hungry person and the burger.

It’s just like Uber: “creative destruction” of an existing good for the benefit of capital. Unsurprisingly, there are substantial links between REEF and Uber, beyond using the same funders and the same model of destroying a market through VC-subsidized behaviors (“gain a monopoly, and pivot to profit.”)

Enter CloudKitchens, a startup from Uber’s notorious Travis Kalanick. Reportedly forced out of Uber for, among other reasons, fostering a culture of casual misogyny and endemic abuse, Kalanick himself has pivoted to become the direct competitor of REEF Technology. The most immediately visible difference is that Kalanick’s firm is going for more juvenile restaurant concepts with names like ‘Egg the Fuck Out” and “Bitch Don’t Grill My Cheese”. And, unlike REEF Technology, which at least laundered Saudi Arabia’s investment through SoftBank, Kalanick cut out the middleman and accepted direct investment from the Saudi murder gang sovereign wealth fund, establishing a direct link between your grilled cheese sandwich and literal genocide.

What does the individual consumer receive as a benefit for all this disruption? The convenience of delivery? There are plenty of other apps that already provide this for a fee. Better food? The opportunity to taste a Rachel Ray branded recipe produced in association with Grubhub?

What does the individual lose? Human contact and community, to begin with; the consumer who does not leave home, who never decides on a whim to try out the jollof rice or the machaca burrito, who simply defaults to a burger, who is given the option to “choose” between two different brands serving identical food prepared identically, is the modern capitalist ideal. They can have any food they want, as long as it comes from the same kitchen; see any film they want, as long as it is produced and distributed by Disney; read anything they want, as long as it arrives via the algorithms of Facebook or Google.

How can we assess the loss of the owner-operated small restaurant? As I mentioned, there are 21 small businesses in this parking lot. Overheads are low enough that hard work can lead to success and a substantial degree of financial independence. In the “marketplace” of the parking lot, any advantages conferred by excess capital, beyond basic signage and cleanliness, are nil. Good food and good service are rewarded with repeat business.

The “ghost kitchen” would change all of that. In place of small businesses there would only be a series of tractor trailers staffed with interchangeable “freelance contractors” cooking, presumably with no benefits or fixed hours. Foodways with centuries of continual practice would be lost or bowdlerized, at best, leaving the mere shadow of a burrito where the real thing used to be.

Increasingly, where there was once a transaction performed face to face—money exchanged between neighbors for goods and services—there is now a series of bewildering intermediaries and abstractions, apps, algorithms, and dizzying amounts of capital. Isolated individuals, triggered by algorithms, silently ordering bland foods delivered to them from parking lots that have been refashioned into surveillance hubs—for the ultimate benefit of Saudi and Emirati sovereign wealth funds. And the Travis Kalanicks of the world. The end result is both clear, and remarkably unappealing.

courtesy of the author

courtesy of the author