While Todd Phillips’s Joker never really bothered to explore alienation, societal disillusionment, and the violence that stems from them in any meaningful way, the film did at least surface these questions, so we could point to other movies that do the job much better–Taxi Driver and King of Comedy were served up on a silver platter by Phillips’s work, and movies like Gaspar Noé’s I Stand Alone and Abel Ferrara’s Bad Lieutenant also came to mind. But ordinary critical responses like these were lost in the month-long spiral of cultural discourse that set my Twitter feed upside down and on fire, as the line between artistic and moral arguments completely eroded, and all were forced by ‘real world’ issues to associate the critical evaluation of those movies with their viewers. The question inescapably degraded, from “is the movie good” to “are the people who like it good.”

“So, what did you think of Joker?”

It was a personal hell, because I really really didn’t want to talk about the movie. What I wanted to talk about was how mad everything orbiting around it made me.

I Stand Alone kept circling in my mind, not only with respect to Joker, but also to the complete misreading of Martin Scorsese’s cinema following his inflammatory remarks with respect to the Marvel films.

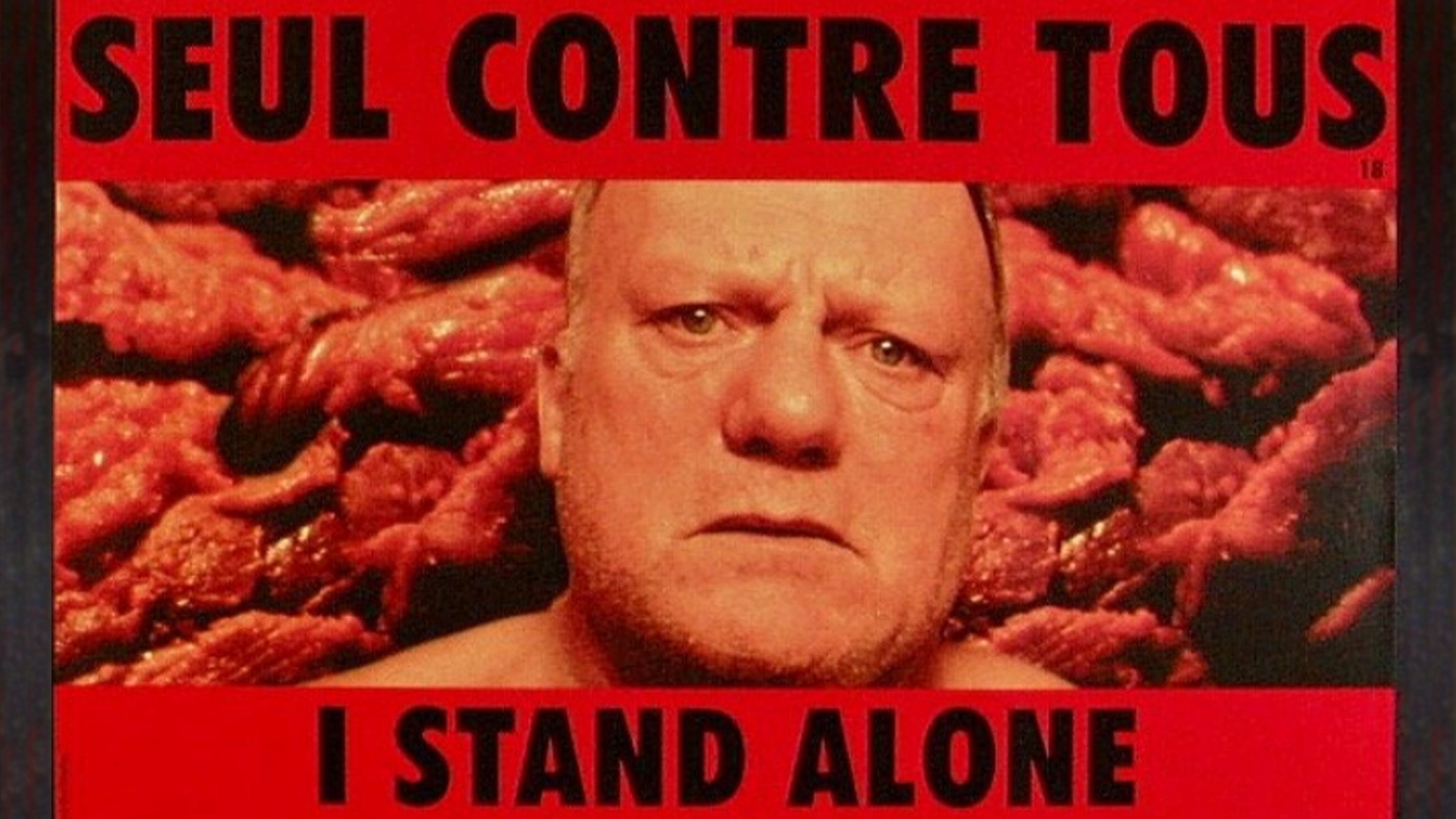

Noé is a filmmaker for who the term ‘divisive’ is but an understatement. Following a burly and disturbed butcher of horse-meat, whose voiceover narration spews unfiltered bile at the state of the world mixed with deeply disturbing sexual reveries about his own daughter, I Stand Alone leaves exactly the kind of bad taste that draws jeers from crowd at the Cannes, as it did twenty years ago. It’s also exactly the kind of movie I respond to with morbid fascination.

How does cinema become a battleground for morality? In a media hellscape convinced that even the most superficial of actions and choices can be forms of praxis, a movie’s artistic merits necessarily take a backseat to the cultural value judgments we can make about its fans and their responses. What is it to “like” a film? Am I supposed to dislike the movies that I actually like? Is there something wrong with me, that I found the contemplation of I Stand Alone’s self-loathing and acrimonious central character to be a worthy and fruitful way to spend my time? That I felt the movie was—dare I say—a masterpiece?

Screenshot: YouTube

Screenshot: YouTubeArt doesn’t come pre-packaged with instructions like a delivery from Blue Apron. Is Goodfellas just too damn cryptic and irresponsible for not signaling to us, like an air-traffic controller, that mafiosos are degenerates? The Butcher in I Stand Alone is a cartoonishly repulsive drunk, but maybe we still can’t quite rule out that Gaspar Noé is endorsing his behavior.

Since the 2016 election everything tangential to politics is being forced into reflecting team sports. Just as the deranged political battleground played out in the 2017 Super Bowl between the Atlanta Falcons and the New England Patriots, movies and filmmakers, too, must be proxies and representatives for ideological sects. Is it possible for Greta Gerwig to release Little Women without the critical community being forced to speak positively about it for the sake of continued representation? Must I, a South Asian film writer, praise every Shyamalan movie in order that studio executives continue to give money and opportunities to South Asian filmmakers? Is this the hostage situation created by the performative “progressivism” in Hollywood that everyone actually wants?

Evaluating cinema through class, race, and gender politics is absolutely necessary. Jonathan Rosenbaum spoke of George Lucas’s Star Wars[1] and Raiders of the Lost Ark[2] in the context of perpetuating the American cultural tradition of genocide with theme-park-like entertainment. Roger Ebert famously lambasted Blue Velvet as being sadistic in its treatment of Isabella Rossellini.[3] These claims, whether you agree with them or not, gain their validity from subjective personal values brought in as a means of navigating the difficult and troubling elements of a film. Rosenbaum and Ebert are great critical thinkers whose deep knowledge of cinema and history give force and refinement to their arguments, what Rosenbaum called, “the objectiveness of personal subjectivity”.

But it doesn’t require any of those skills to evaluate a movie from a simplistic “moral” binary. That kind of Manichean perspective renders Gaspar Noé impossible to come to terms with, because the provocation is the point. There is an underlying comedic dimension to I Stand Alone that makes the anger and violence of its depiction understood to be critical, rather than endorsed. I couldn’t help but smile and shake my head at the timer countdown at the end of the film, prompting viewers to stop watching if they couldn’t handle what was about to happen. It’s easy to consider this self-aggrandizement, but reading and watching Noé, who claims to “tell a terrible story, but you can see that I am having fun because the style of the movie is joyful,”[4] gives a clear indication that he is far from an insensitive provocateur. There is a visceral reaction to his movies because violence like his is hard for us to process as self-critical. Today, his position seems truer and more vital than ever.

It’s easy to dismiss I Stand Alone because its central character is not a good person, yet the movie gives him every ounce of attention. It challenged me to think about this character beyond his actions and words in the film, as a member of the greater societal existence that is man and civilization, and I cherish the film for that reason. There are clear political ideas bouncing around in the movie, like xenophobia burgeoning within the French as they feel themselves losing grip on a growingly diverse society, and a broiling resentment inflamed by helplessness and loneliness that can find no outlet other than unrepentant violence.

Nuance has been extinguished by neoliberalism in order to repress the power of film to address social uprising and change. But art is not political activism, even though it engages with political thought. Engagement with art is not a moral battleground. Morality in the political world, a world where children are locked in cages and the sick die because of lack of access to medical care, is a real morality, entirely removed from the abstract one that exists in the realm of film criticism. The former is a call to direct action based in real events, real beliefs, for actual physical, intellectual and spiritual changes to the life of a nation. The former manifests itself as something tangible. The latter is a matter of performance. Nobody’s life is going to be saved or lost because you hated, or loved, a movie.

[1] Jonathan Rosenbaum, “Multinational Pest Control,” Chicago Reader, November 21, 1997.

[2] Jonathan Rosenbaum, “Declarations of Independents: Movies for Chameleons,” The Soho News, June 10, 1981.

[3] Roger Ebert, “Blue Velvet,” Chicago Sun-Times, September 19, 1986.

[4] Brandon Judell, “I Stand Alone with Gaspar Noé, U.S. Distribs Nearing”, IndieWire, September 29, 1998