Imagine the Atlantic City casinos as a pod of nine whales. An ecosystem forms around them. The man at the center of this story is a barnacle who attaches to their cold underbellies. A tall, black, and bespectacled man who in his 20s started going by the name Renegade or DJ Renegade. A homeless man; or, viewed through a different lens, a man who has slept, for nearly two decades, in opulent, maid-cleaned casino hotel rooms. He is a poker grinder; a low-stakes player who works the casinos’ open Texas hold ‘em tables, slowly bleeding out the unsuspecting recreational gamblers.

When I first reached out to him, I called him Mr. Renegade and he quickly and curtly told me not to do that. Stick to Renegade or Joel. No Mr. His name is Joel Dias-Porter and now I mostly call him Joel.

The poker grinder is among the humblest of professional gamblers. A tournament poker player shells out a big upfront fee with the hopes of outlasting thousands of other players and taking home a huge grand prize. This requires an inflated sense of one’s ability to control the outcome of the game. Once the fee is paid, the chips are just points. They are no longer money. Whoever has all the points at the end gets the grand prize and the game is over.

The grinder buys into the middle of an ongoing game. The chips are money. Every hand is played with cash. Every call, every raise, requires a separate risk. Thus his margins are small. His profits are harvested from weekenders who don’t know the math and don’t realize they’re sharing a table with a professional. Theoretically, the game is never over. You cash out and the game goes on without you.

The casino’s relationship with the grinder is symbiotic. The grinders make their money off the casino’s patrons and in return the grinders keep the casino’s tables warm. Were it not for the grinders, the tables would eventually empty out. And once a table empties, how it would ever get going again? You can’t play a solo game.

But Joel, like many grinders, uses the casinos for more than simply shaving winnings from less experienced players. He also harvests the casinos’ comps to reduce his cost of living to nearly zero. In an effort to entice the recreational gambler, who will go on to lose his shirt, the casinos dangle comps: Free-play money, hotel rooms, casino restaurant points. If you risk a certain amount of cash, the casino might offer a free night in a suite or a meal.

A casino will comp up to two nights in a row on their properties. But there are nine casinos to choose from. So Joel has lived his life in two-night stints, in five-star hotel rooms, eating at gourmet restaurants, then packing his bags, and walking up the boardwalk to his next two-night destination.

Joel is a poet.

He won two National Haiku Slam Championships in the ’90s. Prior to that, he’d moved into a homeless shelter so that he could spend less time chasing rent and more time reading classic literature. His dissertation on the true author of the works of William Shakespeare is in the French National Library. He was a local legend on the D.C. slam circuit. He contributed the lead poem to the April 2015 Poetry magazine issue dedicated to hip hop poetry.

My favorite of his poems is this one:

Your eyes-

green pistachios

half open

The celebrated author Ta-Nehisi Coates was in college at Howard University when he met Joel. Coates remembers Joel, then in his early 30s, reading at an open mic wearing his signature Pittsburgh Pirates Starter jacket, and being floored by how incredible the performance was. Shortly thereafter, Coates read a poem of his own; the two fell into conversation.

“He was very nice and very kind and very supportive,” Coates said. “But he went off on what was wrong with my poem. And we got into this argument about it. And he was smart. You had to respect what he was saying.”

“You know, I had professors at Howard,” Coates says, “but probably the most important professor in my life was Joel Dias-Porter at that point.”

Though he was never a student, Joel haunted Howard’s stacks. He DJed house parties and performed poetry at open mic nights. A loose scene popped up around him, including contemporaries like Brian Gilmore and Kenny Carrol, and younger writers like Coates, Terrance Hayes, Jelani Cobb, and Yona Harvey. Coates called them a “belligerent” group.

“But, I mean, in the best sort of way, like they were belligerent like my dad was: very argumentative, very opinionated, you know, a lot of back and forth,” he said. “But as belligerent as these folks were, they were well-read belligerents, which is, like, the best kind of person.”

“Iron sharpens iron,” Joel said of this time.

I’d heard that Joel and Coates would go to an IHOP near Howard together and just sit in silence, reading for hours together. “Hell yeah, we would,” Coates said. And there was a Borders at 20th and L where they’d hang out in the poetry section.

“I don’t mean like sit there and talk. There’d be a lot of silence,” Coates said. “Or we’d go to the Barnes and Noble that used be in Georgetown. They had a beautiful poetry section. We would just go there and chill and look through shit. To have somebody like that is just so so important.”

It was Joel who introduced Coates to the Richard Wright poem, “Between the World and Me,” which would inspire the title of Coates’s most well-known book.

“Literally the way I write, with high attention to lyricism and beauty and that language should be beautiful,” Coates said, is attributable to Joel’s tutelage. “I learned that from him when I was working with him as a poet. [We studied] Yusef Komunyakaa, who’s had a huge influence on the way I write. I didn’t know what the fuck he was talking about. I was a kid. I was like: What is going on here. To read it and have Joel there… and listen, this is obvious, but Joel was Black. Like he was Black and understood the desire to reach a Black audience and talk to black people. He got that. It was a special thing man. It really was.”

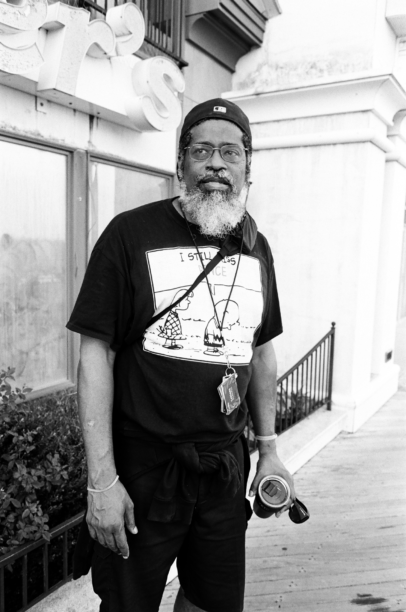

Photo: Alex Phillipe Cohen

Photo: Alex Phillipe CohenThese days, Joel’s got a full, sculpted graying black beard and mustache, big, thin-framed reading glasses, and he always wears a black baseball cap repping one of his beloved Pittsburgh sports teams. His wardrobe, too, is almost always all-black, sometimes with a splash of Pittsburgh yellow or Prince purple.

He has focused skeptical eyes, a resting poker face, and a rare but contagious patchwork smile. He’s piercingly honest, obsessive-compulsive, and believes himself to be “on the spectrum.”

He moved to Atlantic City in the early 2000s with the intention of becoming a grinder. He describes the move — from Washington D.C., where he had a community, and a child — with complete disinterest.

Photo: Alex Phillipe Cohen

Photo: Alex Phillipe CohenAtlantic City is the most romantic place in the world to me. Pine barrens, the ocean, marshes, casinos, and no organized arts culture. A noirish, urban hodgepodge of prohibition-era and Bladerunner era-architecture on a frozen, gray island that looks, on a map, like it’s shedding off of New Jersey. Most people who have opinions of Atlantic City make fun of it. I know people who love Atlantic City who would never live here. It would never even occur to them. I know plenty of people who live just outside of Atlantic City, who claim to live here. A lot of the people who choose to live here—truly live within the city—are beautiful weirdos.

Joel has no real opinion of Atlantic City: He needs the casinos to live. It’s closer to his son, a professional gamer, than is Vegas. He wishes it had a real bookstore.

“I’ve been to the beach maybe three times since I moved here,” he told me as we walked the boardwalk this summer. “Always when someone is visiting me.”

Joel has a beautiful voice.

He writes at the poker table. I find this to be the pinnacle of romance. It’s 2 a.m. in some shitty casino on a barrier island, on the edge of an inlet. Dale Chihulys overhead. Sad men fiddling with chips, playing slowly. Tintinnabulation of slot machines. This, on its own, appeals to me. The loneliness and pathos. The unnaturalness of it. Like living on a submarine, or as a lighthouse keeper.

Joel’s getting bored.

“You never ever ever want to get bored at a poker table because then your cards will start looking better than they should and the next thing you know you’re in some bad mathematical spot because you got bored and you started gambling.”

So he pulls out his iPad while the other players decide on their hands. Reading news articles he comes across the word, “Psychopharmacology.” The study of the effects of drugs on the brain. Joel thinks of love. An interesting title for a love poem, he thinks. He’s been struggling with a particular love poem. Maybe this new word is the controlling metaphor, he thinks. The game comes back around to him. He tells the dealer to deal him out. Now he’s just alone with the poem for half an hour while men gamble around him.

I’m iffy on poetry. A lot of it feels pretentious or soullessly opaque. When Joel describes his approach, I have an increased appreciation. He lays a foundation that works rhythmically and then tries to upgrade the words. Replace the boring adjectives with concrete adjectives that immediately conjure feeling. Firetruck red. Raspberry beret. Two of the lines of his haikus are often separate thoughts, brought together by a third line. It’s all very mathematical. I’m surprised at how that appeals to me. I ask him about how being on the spectrum impacts his work.

“One big advantage that I think I’ve always had is, a lot of people, a lot of poets in particular, think of emotion here, and technique over there. Whereas that’s never made sense to me. That’s not a dichotomy. You can’t cut your wrist open and bleed on the page. The only way the emotion gets on the page is through technique.”

“And sometimes this is a problem and I’ll be talking about poetry with poets and I’m always talking about technical things and people are like what about emotion. And I’m like well what about it though? It’s all technique.”

I recognize that there is something potentially sad about Joel’s life. He is mostly alone in Atlantic City. For me, he represents a fantasy of isolation, my sometimes-desire to be completely unattached. But I’ve never taken it to his extreme. I think of Joel as a heroic survivalist and someone who’s managed to place a firewall between his finances and his art.

I asked Coates if he thinks of Joel’s life as, in any way, tragic.

“You know what, because he’s so brilliant, you name the successful people he’s worked with, right? I think he might have gotten what he wanted… He’s always been happy and joyful too. Life is life and I’m sure there’s some things that didn’t go the way he wanted them to go but I don’t know man. There’s this tendency to say, you know, he’s making a living off poker, that’s so sad, somebody with that potential should be doing X, Y, and Z. But what if that’s what he wants to do? What if that’s what he wants? What right have I to say, you know what I mean.”

“When I think of tragedy, I think of someone who wanted other things. And I’m not sure he wanted other things.”

Every time Joel and I talk, I try to get a sense of whether he finds this strange lifestyle fulfilling and he’s perplexed by the question. He doesn’t want a boss. He lives in five-star hotels. He wants to keep writing his poetry. The lifestyle checks the necessary boxes. There’s nothing else to it.

When I ask him about his aspirations, he often makes analogies to jazz greats. And he talks about their obsessive study and practice. They make strange, unorthodox decisions to honor and strengthen their craft. They lock themselves away to become the best. They study endlessly to become the best. Sharpening iron. He tells me about their discipline and unorthodoxy.

Then he gets uncharacteristically excited and forgets the question and he ends up telling me jazz stories for minutes or hours.