Linate (LIN) is the smaller of the two international airports serving Milan, just a stone’s throw from the outer ring of the city. When I was younger I found myself stranded there one summer night; after seeing a show at a popular club nearby, I’d missed the last bus to the city center. So I went to the airport, the only place still open, and spent the whole night wandering around, too scared to sleep in the waiting area with all the drunk homeless people. There were no check-in counters open and no flights. Nor would there have been any sign of Vito Cosmai’s postal box at the airport, C.S.E. Box 22, which had been emptied shortly after his death some six, maybe seven years before.

I know the story of this postal box because, when I learned of its existence five years ago, I was naive enough to go looking for it. I did not find it, nor did I find many other things I went looking for in my years-long quest to piece together the details of Vito’s story, which is both engraved in the subconscious of most Italians, and all but forgotten—or worse yet, disappearing without ever really having been grasped at all.

“Emoscambio” basically means “blood exchange,” and these enormous graffiti were a kind of guerrilla marketing for the project to which Vito Cosmai devoted his life: the Italian Institute of Physiology. This was not exactly a real institution. Its headquarters were in the garage of Cosmai’s house in San Felice, a gated community near Segrate, the suburb of Milan which is also home to the Linate airport. Sometimes, the murals also featured a phone number: 02-7530148, where callers reportedly heard an answering machine recording of Cosmai explaining his very weird medical idea: through regular exchanges of blood between men and women with similar body types, he claimed, it was possible to cure every disease and even attain immortality. He concluded with an invitation to the weekly conferences he held in his garage, and a request for money to finance his studies, to be sent to his p.o. box at the airport.

Born in 1938 to an affluent family who’d come to Milan from the southern town of Bari, Cosmai studied accounting, helped his father in the family’s small textile trading business, and lived an unexceptional life. All that changed at the end of the 60s, when, for unknown reasons, he nearly died. “I had two bleeding ulcers, I know what death is, and I don’t want to die. No one should die,” he declared in an interview with a gossip magazine a few years later, in 1973, when Emoscambio first came into the spotlight. “You think I’m crazy, right? Everyone thinks like that, just because I want to save humanity from the catastrophe”.

To this noble goal, saving humanity, Cosmai would dedicate the second half of his life. In 1971 he left his job to manage the Italian Institute of Physiology, and to travel through Italy in his Bedford minivan stocked, presumably, with paint and rollers, writing ΣMOSCAMBIO in massive letters everywhere he could, until 1999, when he died alone and in poverty. In these 30 years, he succeeded only in popularizing the name of his theory: most had no idea what it meant. Some supposed the murals signaled some kind of emergency medical structure. Others thought it was a drug dealers’ code. A few thought aliens were responsible (it’s true, I found mention of this in an old post on a now-abandoned online forum).

courtesy of the author

courtesy of the authorI strongly doubt that Cosmai ever had a meaningful following, or attracted much in the way of donations, even though Emoscambio’s Italian wiki insists it was a “cult.” But I know for sure that he tried to verify his theory of blood-exchange, because I found a picture in a magazine article from the 70s about Emoscambio, showing Cosmai putting a needle in a woman’s arm.

I should mention that before Cosmai, an earlier version of the blood-exchange-to-rejuvenation theory had already been developed by the Bolshevik revolutionary, physician and author Aleksandr Bogdanov [paywall], who wrote about it in his 1927 book The Struggle for Viability: Collectivism through Blood Exchange. Bogdanov even made some experiments at the research facility he founded, the Institute of Haemotology and Blood Transfusions in Moscow. He died in one of those experiments. I found that Bogdanov’s works on the subject were translated in Italian only after Cosmai had started Emoscambio, so how, or if, the two projects might have been connected is unclear.

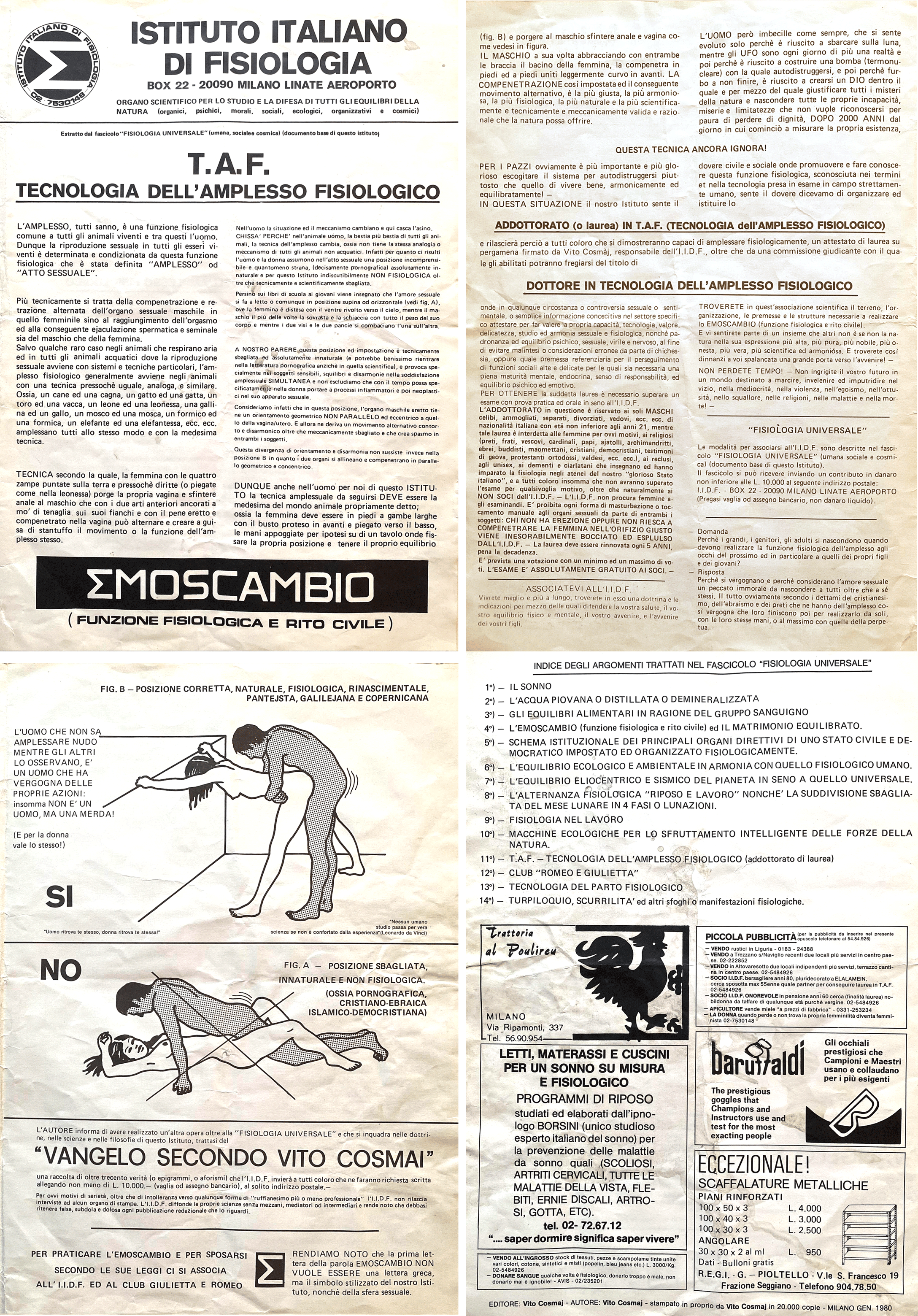

Cosmai self-published three books: Fisiologia Universale (Universal Physiology, 1978), T.A.F. Tecnologia dell’Amplesso Fisiologico (T.A.F. – Technology for a Physiological Sexual Intercourse, 1980) and Il Vangelo Secondo Vito Cosmaj (The Gospel According to Vito Cosmai, 1980). All three are lost forever: we have only their titles, a summary of the content for the second, and the index of the third. For us today, these books are like texts from the ancient world. Or even worse, since the lost plays of Sophocles could still theoretically reappear in a newfound incunabulum or something like that, while all of Cosmai’s books, though only a few decades old, might easily have been lost or destroyed since the author’s death.

All that remains of Cosmai’s writings comes from a flyer he distributed in the center of Milan. There are a few versions of the flyer online, including the one some guy took and for whatever reason kept for decades, until he tried to sell it on eBay; I bought it as a present to myself for my 30th birthday.

The flyer provides a rich source of information on Cosmai’s theories—in part it’s an early instance of what is now known as shitposting, and in one version it also includes a fake advertisement for a company producing chastity belts (model “Immacolata Scopanda,” produced by the nonexistent “Virgo-Virginis Spa” company of Palermo). The flyer also informs us that in the 80s Cosmai organized a monthly conference in a restaurant called Osteria del Nucleo in Riva San Vitale, a small town in the Italian-speaking part of Switzerland. I asked the municipality of Riva San Vitale about that, and they told me the restaurant is long gone, having closed after the owner’s death.

Over the years, the ideas Cosmai advanced became more and more complex and improbable, with the blood-swapping theory gradually losing ground to a new, equally miraculous cure for every disease: having sex doggy style (as helpfully illustrated in the flyer).

I tracked down Cosmai’s only living relative, a nephew in his 70s, and he gave me most of the biographical details available; when and where Cosmai was born, his family background, and the time, place and cause of his death. At one point this nephew agreed to meet me to talk about Emoscambio, only to cancel on the morning of the scheduled day, explaining that the family had considered Vito a source of shame.

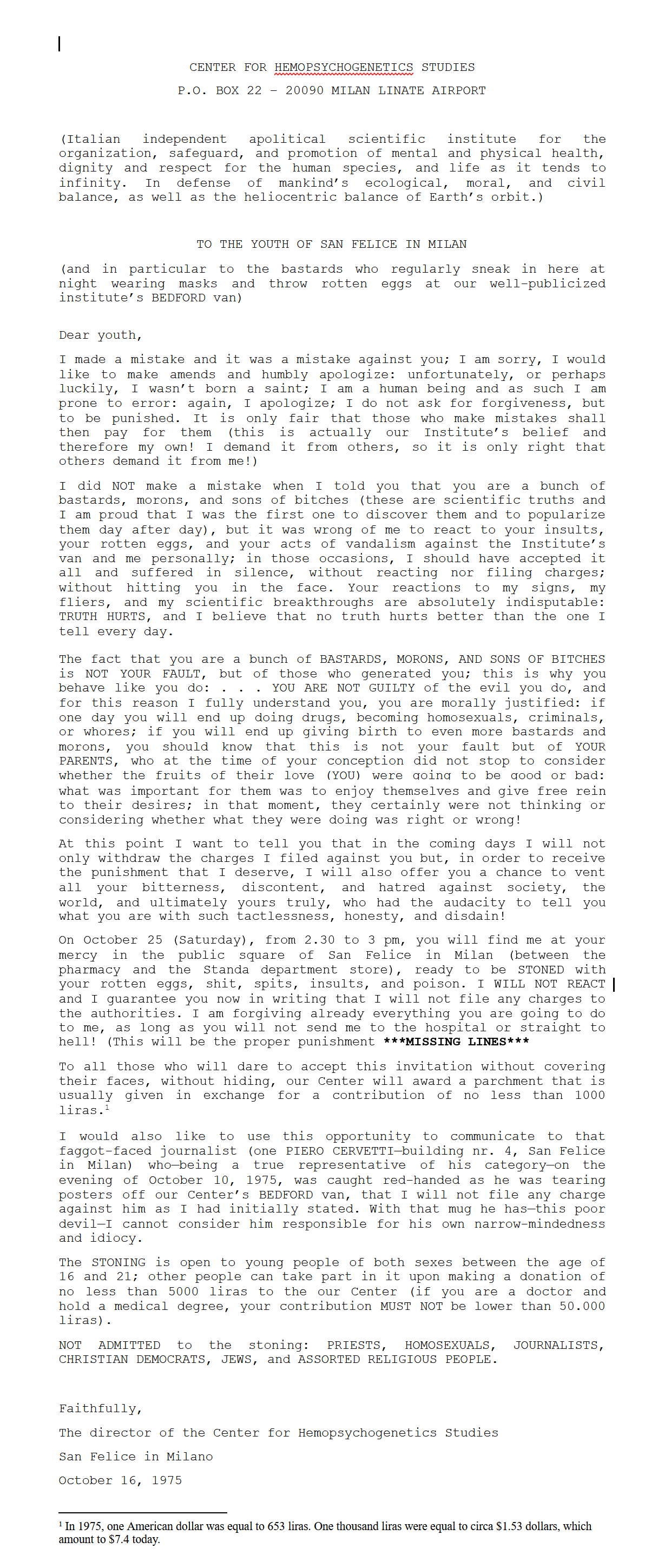

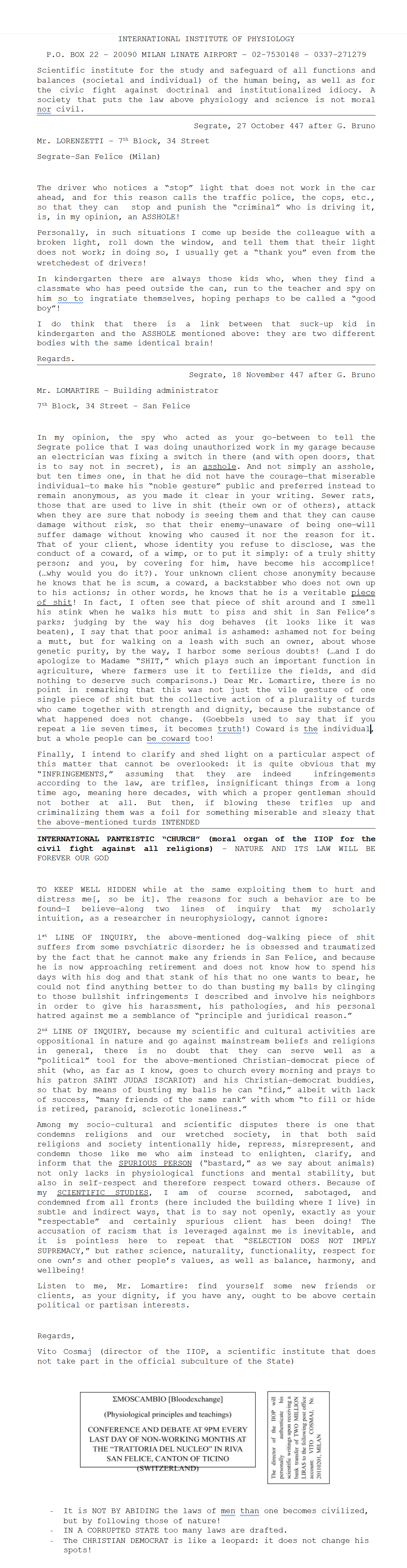

But on a visit to San Felice, the gated community where Cosmai lived all his life, I had little more luck: I met Luigi Parodi, an older resident who used to publish the parish newspaper. He showed me some letters sent by Cosmai to the paper in the 70s that were never published, because they were full of curses and blasphemy. Two are provided here, with excellent translations by Lorenzo Andolfatto. (I will add that it’s weird to read Cosmai in translation, it reads a little bit like William T. Vollman. It feels way more chaotic in Italian.)

Reading these letters, a strangely moving picture of Cosmai emerges: a lonely man, tormented by the neighborhood kids, avoided by his peers, and full of resentment. He curses against whomever it was who, rather than warning him that his car had a broken light, decided instead to shop him to the police. But he’s also funny, sarcastically apologizing for getting angry at the kids mocking him; he invites all the neighborhood residents to the main square on a given date to pelt him with, and I quote, “rotten eggs, excrements, spit, insults and venom”, adding that he will not react to these deserved insults, and that his offer does not extend to “priests, homosexuals, journalists, Christians, Jews, and religious people in general.” Also he proposes payment of a small fee for those wishing to participate in this spectacle of humiliation. He was desperate for funding, so he could help humanity defeat death.

There’s also a mystical dimension in Cosmai’s work, and I suspect that’s what The Gospel According to Vito Cosmai was about. The surviving flyer features spurious-looking quotes from “great men” including Napoleon, Leonardo, and Oscar Wilde, alongside Cosmai’s own; one gets the sense that his last book was likely a collection of aphorisms, perhaps something akin to Mao’s Little Red Book but concerning spirituality and “alternative” medicine.

There’s support for this theory in a stray reference to a certain philosopher called Charvakas, whom Cosmai regarded as his “master,” according to Elio, a middle-aged man I met who, as a young student, had attended one of Cosmai’s weekly garage meetings. I haven’t been able to track down Charvakas, but “charvaka”, I found, is an ancient school of Indian materialistic philosophy. Little is known of it, because its foundational texts survive only in fragments—just like Emoscambio.

After the 70s, when he started his preaching and was featured in some magazines, and the 80s, when he published his books and printed and distributed his flyer, Cosmai disappeared from view. But just before his death at the end of the 90s he reappeared with a website for the Italian Institute of Physiology. He exchanged e-mails with another guy from Segrate, Gian Paolo Vanoli, now famous as an anti-vaxxer and a supporter of urine therapy. Vanoli told me that Cosmai had had a little following, and that they met only one time in a café to talk about their respective theories: “He wasn’t stupid. With him you could talk about pretty much everything.”

In the early aughts a website, emoscambio.com, appeared, a copy of which you can still see on the Wayback Machine. The owner of the site, Salvatore Mocciaro, is an architect/designer/visionary interested in artificial intelligence; he holds some weird patents, including one for a system designed to project advertisements on the horizon, like mirages. He is also untraceable; no known address, no social media accounts. I strongly suspect it is Mocciaro who, in the year following Cosmai’s death, attended an annual makers convention, the Inventor’s Show, where he, or someone, presented the Emoscambio theory in its original form (blood-exchange to attain immortality). There was a stand at the convention with a banner that featured some slogans taken from Cosmai’s website: “Cavie umane cerco” (“Human guinea pigs wanted”) and “Vigliacchi svegliatevi” (“Cowards, wake up”).

The final piece of evidence we have on Cosmai’s life is a short newspaper article dated 1999. He was in Turin, distributing blasphemous flyers protesting the exhibition of the Holy Shroud with a 34-year-old Italian guy and a 23-year-old homeless man from Romania, whom he’d hired to help him in his task. He told the reporter that his institution was devoted to the “civil fight against the crimes that Humanity is committing against itself and doesn’t want to recognize.” He also said that he was protesting because the Church is lying, Jesus was a liar and Mary was not a virgin, but a whore. The three of them were promptly detained and charged with contempt of religion.

So far as I know, those were Cosmai’s last public words; he died of liver cancer a couple of months later, in February 1999. He was 61. The postal box at the Linate airport was still there at that point, and as his nephew told me by phone, “he received some letters, they were there when I went to empty it after his death”. So maybe Vito was not all alone in his fight.

For a long time, I didn’t really know why I became obsessed with this little, almost forgotten story. I first heard about Cosmai in 2015 and after that I spent years researching him, trying to find out all I could, before all that was left to be discovered was lost forever. It was only some time later, when my researches reached an end and the only remaining sources had refused to talk to me or proved untraceable, that I realized I’d crossed Cosmai’s path so many times without ever knowing him. That something real and alive and surpassingly strange had passed through my own world, leaving virtually nothing behind.

I’ve always lived on the other side of the city, but my father worked for years in San Felice while Cosmai lived there: I refuse to believe he never saw him walking around. And though Cosmai had always lived across the city, the hospice where he came to die is in my neighborhood, right next to the church, at a five-minute walk from my parent’s house: we were so close. We were also born on the same day, December 20th. And when I was just a little baby, my grandfather, who was an aircraft pilot during WWII, often took me on the weekends to see the planes taking off in Linate, IATA: LIN. I refuse to believe that we never crossed paths with Cosmai there, coming to check his postal box for the support he tried to summon from the world.